Contrary to what Barnett Newman declared, one never “starts from scratch,” even if it is true that “the old stuff was out” in the all-out crisis brought on by World War II and everything that preceded it. Two exhibitions have just offered fresh reexaminations of the postwar period. The most recent one took place at Lyon’s Museum of Fine Arts, where the curator, Sylvie Ramond, along with Eric de Chassey composed an intelligent picture through their presentation of works and artists who for the most part had previously been neglected: Americans from the West Coast, anti-Nazi Poles and Germans who had escaped censorship, and so on.

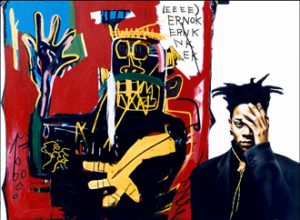

Right beforehand, at Barcelona’s MACBA, our guest speaker Serge Guilbaut dreamt up Be-Bomb. Guilbaut’s writings are key to understanding the upheavals that have take place on the artistic stage. Relying on a number of texts–including his own caustic and much-talked-about book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, which was first published in the United States in 1983–Guilbaut reopens the file on this period by shedding light on his own enlightening exhibition. In Be-Bomb, works of art as well as debates around the issues of the day were brought back to life through a rather vivid and well-documented presentation of numerous films, archival material, magazines, and manifestos. He shows how art is in no way a neutral form of activity and how it constitutes, rather, a territory of relentless struggles upon which opposing world views clash. For the author, it does not suffice to note that one set of views won out over the other, for what he wants to show is why and how that was so. He accomplishes this by bringing works of art and documentary evidence into mutual confrontation while exhibiting the sensitivity that is due to the art itself but also to a history that has largely been forgotten in the ultimate hit parade of our judgments of taste.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of June 5 2008

On an Exposition:

Tempestuous Transtlantic Culture,

1946-1956

Serge Guilbaut

“France was liberated from the Krauts; it must now be liberated from the jerks.” (Archives du Peintre Wols)

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Circus Girl Resting, no date.

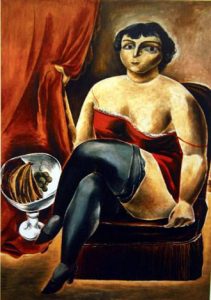

From what we are told by the abstract painter Wols, the postwar period was not going to be either easy or completely restful! After the war, everything in France, of course, had to be rebuilt, but especially its cultural and symbolic image had to be remade. Paris, the capital of the arts, which had suffered not only from the Occupation but also and especially from collaboration, had to find itself again and to reinvent itself. What Wols saw and felt so deeply in the recesses of his spare hotel room, which also served as his studio, was the established cultural powers’ inability to recognize and to defend certain new forms of modern art that expressed the malaise then seeping into the consciousnesses of a great number of people. This anxiety, rooted in modernity, that lay at the heart of the issues haunting the West, and which New York embraced, nonetheless too often seemed to be ignored by French cultural institutions. Indeed, through the voices of and positions taken by its critics and museum directors, Paris had a hard time seeing or accepting art located at the antipodes of what had always been the image of France: an optimism mixed with luxuriousness and sometimes with voluptuousness.

The Grasshopper and the (American) Ant

Bikini atoll atomic bomb test, 1946.

The exhibition Be-Bomb: The Transatlantic War of Images and All That Jazz was an attempt to bring out this symbolic friction. By presenting on its walls the mutual lack of understanding between Paris and New York, this show let us see the intense cultural production going on in the West as it grappled, up to 1956, with a frightening cold war that had recruited culture almost by force into its political arsenal. The exhibition tried to highlight the different artistic and political currents that were dividing each culture and that participated in the elaboration of quite specific and varied identities. It also was intended to show the complexity of these two artistic and political scenes by laying emphasis on the different currents that shared them while setting out to present, of course, the currents of artists who had received international recognition but also those ones that had not succeeded in getting their message across to others, despite the quality and inherent interest of what they had to say.

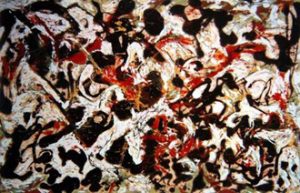

Jackson Pollock, Big Dipper, 1947.

Moreover, thanks to the presentation, along the way, of popular and avant-garde films as well as of jazz music, the exhibition set out to delimit and to analyze the vast cultural field of battle onto which modern artists had been hurled. It is rather striking to see how much France, like the United States, interiorized stereotypes of their respective cultures. On this account, America was brutal and violent but free, and France, the land of culture, was suave to the point of decadence as well as bursting with internal contradictions. One was rough and unfinished, the other smooth and refined. The positive characteristics of the one became for the other negative qualities.

In their reconstruction efforts, Parisians, for example, tried to capitalize on the image of luxury traditionally afforded by haute couture and Parisian fashion without truly realizing all the negative aspects this image conveyed as the Cold War was starting up and as all signs of culture were becoming highly symbolic.

Admiral Blandy and Mrs Blandy celebrate operation Crossroads with an atomic cake, 1946.

While Paris continued to be, for Americans, the center of the culture of luxury as well as of fashion, at the same time the latter confined the City of Light to a somewhat ethereal space that had no genuine hold over what was then going on. While The Theater of Fashion—a haute couture exhibition presented on doll-sized models because of rationing–enjoyed considerable success in the United States in 1945-1946, the exhibition of paintings entitled Painting in France 1939-1945 was gleefully reviled by American critics on account of its old-fashioned character. Paris was becoming artificial and somewhat effeminate, whereas New York was appropriating for itself the most up-to-date intellectual and virile forms of artistic production.

Thus, in Paris, while Christian Dior had won acclaim for his New Look, which transformed the militarized woman of the Resistance into a desirable and carefree being, American critics used her to define the French soul in general.

Christian Dior’s “New Look”, Bar Suit (photo Willy Maywald), 1947.

The buxom mother-woman who was the heroine of Vichy had of course been purged by then, but by becoming a desirable woman, this erotic mistress-woman symbolized the loss of intellectual power. It was easy for New York to take this place since Paris, in replaying its old cards of a tradition of luxury, calm, and voluptuousness, seemed unthinkingly carefree to American critics worried about looming confrontations with the USSR. For others, however–artists like Jean Fautrier, Bram Van Velde, Wols, Pierre Soulages, and Hans Hartung–this flashy luxury and carefree attitude were replaced by a critical countenance which was also depicted on stage by Boris Vian, Marcel Mouloudji, and Juliette Gréco.

These “cellar rats” of the Latin Quarter defined the desires of a new generation that was now in breach of norms in a society where the existential was replacing the artificial. The black of jumpers was replacing the pastels of organdy dresses while the authenticity of the cellar, of the inner world, was replacing the superficiality of the surface.

Cold War rhetoric tended to present two opposing camps, each one employing against the other an entire panoply placed at their disposal by the media. Now, political reality was, even during the Fifties, more complex, more contradictory, and sometimes more confused. Under such conditions, one will not be surprised to learn that the ideological positions and attitudes adopted by intellectuals were always complicated and often imbued with irony. In fact, in order to understand the Paris world of art between 1947 and 1951, one must mull over what the poet Christian Dotremont, of the “revolutionary Surrealist” group then connected with the Communist Party, had said.

Jean Fautrier, Nude, 1943.

To a journalist from Carrefour who asked him in 1948 what he would do if Soviet troops invaded France, Dotremont, in full possession of his dialectical powers, answered without beating an eyelash that he would take the first plane leaving for the United States.

Peace, Freedom, and Fantasy

As for America, it knew that it had become the leader of the West and the main line of defense against Communist ideology. It had very quickly become obvious that, if the United States wanted to guarantee itself a position of strength in the postwar arena, it had to gain cultural supremacy, or at least broad cultural recognition–which would help in persuading the rest of the Western world that their military and economic hegemony did not represent, despite what some people were saying, a threat. On the contrary, not only could one rely on it but one also had to rally around it.

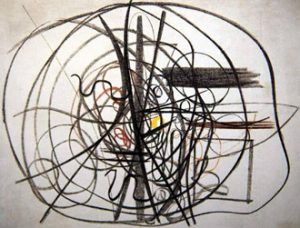

Hans Hartung, T1948-38, 1948.

Indeed, it had to be shown that America was defending and cherishing the same values and the same complex civilization as the Europeans. For the American avant-garde (and by that term I am alluding not only to artists but also to art critics and to individuals who make financial contributions to museums), it was a matter, first of all, of persuading a portion of the public, even in the United States, that the works they were in the process of creating or those they were defending (the Abstract Expressionists) were just as sophisticated as those produced by the modern European masters. It was obviously going to be necessary, after that, to convince the Europeans of the intrinsic quality of specifically American artistic characteristics and of their universal supremacy–though that was going to prove distinctly more difficult to accomplish.

Lee Miller, Civilians and US soldiers with dead prisoners Buchenwald, Germany, 1945.

Thanks to the writings of Clement Greenberg and to the activist stance of the major American museums, modern art in the United States between 1948 and 1951 was going to be not only protected but also dressed up in new clothes and presented as the sole movement capable of refashioning the image not only of postwar America but also that of the West as a whole. This was a completely new phenomenon for the United States. To judge by the events surrounding the episode of the Institute of Contemporary Art of Boston–which came into conflict in 1948 with the Museum of Modern Art of New York over the issue of the word Modern, considered dangerously elitist by Boston–it is clear that people like Clement Greenberg, Robert Motherwell, Alfred Barr, and Nelson Rockefeller, to mention but a few names of the people upholding a certain ideology (which we could describe as liberal new modernism, in order to distinguish it from the watered-down academic modernism then in vogue), felt it quite necessary to promote a kind of art that was based on individualism and freedom of expression, as opposed to productions pertaining to a socialist or populist ideology.

Irene Rice Pereira, Green Mass, 1950.

It was possible for New York’s Museum of Modern Art to defend in this way the so-called extremist Abstract Expressionists because it was easily demonstrable that modern art did not pose a danger to America and that, contrary to what many on the Right had tried to insinuate, this form of art was in no way harming American values (the Soviets, following the example of the Nazis, were ferociously hostile to it). Modern art–as it happened, its most advanced bastion–insolently held its own between the two blocs traditionally opposed to it: the Right and the Old Left. It is this central, and therefore crucial, position that served for Albert Barr as an argument in 1949 when he wanted to convince Henry Luce, the head of Life, to alter his magazine’s policy toward the novelty of Abstract Expressionism. And Barr added that one must not be afraid of modern art–which he showed was not destined to destroy American values.

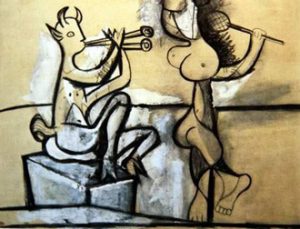

Pablo Picasso, Faune, musicien et danseuse, (Faun, musician, dancer), 1945.

Extremely divided, the Parisian world of art was not at all inclined to consensus. And the violence of the impressive campaign organized by the popular and powerful Communist press kept it from achieving unity when, after 1947, the Party rejected the idea that abstract art might have any value at all. As the review Esprit indicates, the French Communist Party (PCF) also conducted an active campaign of anti-American propaganda. The “peace offensive” launched starting in 1947 was quite impressive, as much on account of its relentless attacks against American culture and the American way of life as on account of the portrait it painted of America as warmongering. For the entire time this offensive was to last, the PCF, knowing the importance of France’s cultural image, guaranteed itself the support of a large number of famous intellectuals, including Tristan Tzara, Roger Vailland, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, Pablo Picasso, Fernand Léger, Jean Lurçat, Edouard Pignon, and André Fougeron. In this battle for the soul of France, art was going to become one of the most prized stakes–without, for all that, offering a rallying point. Neither the political scene nor the world of art could foster a viable middle ground. The Parisian art world resembled a shattered mirror–each of its factions dreaming of gathering together the broken pieces so that that mirror might again reflect the grandeur of France, though in its own image.

As if by magic, as soon as the Communist ministers ceased to be part of the French government, there would no longer be for the PCF anything but one artistic style that could fittingly represent the working class. A revised and updated version of Socialist Realism was to become the Communist criterion in matters of aesthetics. Straightforward and easily accessible to the masses, this art form had its roots in the French tradition (David, Courbet). The writer Louis Aragon would become the theoretician of this current, and the Realist painter André Fougeron was to be its leader. Through Realism, one could hold back the tide of abstraction and, at the same time, violently attack capitalist decadence.

Nevertheless, what really is to be noted here is that the contemporary art being produced in Paris at the end of the 1940s and through the 1950s shared most of the characteristics of what was then being produced in the West in response to the horrors of war: a strong interest in abstraction as well as an unconcealed fascination for the force of the individual. But as this art was often played in a different key and did not harmonize with the formalist art criticism being developed in New York, American eyes were incapable of seeing what Wols, Fautrier, and Antoni Tapies were expressing in the early 1950s. Their detached silence and their introspectiveness did not fit into the well-coached Greenbergian outlook of American criticism. Everything that did not fit into this perspective quite literally was neither seen nor known. For the first time in the United States–and this, as early as 1948–avant-garde art had become lodged at the center of American identity. Few people in France realized this, and very few had heard of the book Thomas Hess had published in 1951, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase, where the New York School was placed at the end of a long line of artists who represented the tradition and the renewal of modern art. The book’s layout was clear. All the reproductions of American works were in color, those of European artists were tiny and in black and white. Responding to a questionnaire entitled “Is the French Avant-Garde Overrated?” proposed by the review Art Digest in September 1953, Greenberg answered unambiguously: “Do I mean that the new American Abstract painting is superior on the whole to the French? I do.” This now-famous reaction laid stress on the fact that French abstract painting was no longer a match for America’s since the former had become soppy and feminine. The French knew how to be inventive, of course, but unfortunately they “finished,” they “polished” their canvases. As for the Americans, they were, according to Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, rougher, more audacious, and more robust. According to Greenberg, what was being produced in Paris was “tame,” which conjures up an image of castration and slavery. Paris was like a lion whose teeth had been removed. Paris was now purring like a cat, and that was not the image the West needed in order to oppose the dangerous Communist hordes.

Drip and Stains

Jackson Pollock, Search, 1956.

What was at stake at the time, and what the critic Charles Estienne understood very well, was in fact the creation of a new and modern identity for France–an identity rooted, he thought, in a long and glorious national past but also armed with a contemporary force. What was needed, but that had not truly been assimilated, was the construction of a present that would be open to a universal future, yet clearly built upon French foundations. Of course, the Americans were dripping, as Estienne knew since he had taken a vague interest in Jackson Pollock, but what to him seemed much more interesting was that the French themselves were staining! The French were making “stains [taches].” “Tachism”–which, according to him, had been invented around 1952 by painters whom he was defending, such as Marcelle Loubchansky, Simon Hantai, Roger-Edgar Gillet, Jean Degottex, René Duvillier, Jean Messagier, Fahr-el-Nissa, and even the American Alfonso Ossorio–was also, like the New York version, an art of free expression. But in Paris, he explained, expression always started again from scratch [B partir de zéro], from the inarticulate, from filth, from the stain–like the placenta, as he liked to say. This was a birth with deep roots. This kind of art, Estienne said, employing the fashionable phrase drawn from Roland Barthes who had just published his famous book Writing Degree Zero, is a total re-creation. “The Stain is the degree zero of artistic writing,” he wrote. This was a kind of art that, as Estienne pointed out, emerged from the individual rather than from any style. Tachism was–we often forget–a parallel French version of American Abstract Expressionism, a type of painting created after the war and mustered into service by Estienne in order to neutralize the publicity people like Michel Tapié were giving the Americans by inviting Pollock to “be with us” in 1952 at the Facchetti Studio. The drip and the stain were two sides of the same coin, the heads or tails of contemporary art. This contemporary-art scene was clearly divided between those who were looking toward the US and those who preferred to show an interest for neutralism. Michel Tapié and Georges Mathieu, for example, were so immersed in the ideology of freedom being advocated at the time by the United States in opposition to the notion of peace being defended by the Communists that they were quite often suspected of “collaboration” with America. What made things even worse was that they also published, as the propaganda war was stepping up, a review entitled The United States Lines Paris Review, for a transatlantic luxury-liner company, in which they were not afraid to speak of “the vitality and the grandeur of our Western civilization on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.”

In very clear opposition to this definition, Estienne, with the help of André Breton, dug deeply into the French past until he found–as surprising as this might seem–a relationship between the art of the Celts and that of the “Tachists.” The Celts, perceived as the direct ancestors of the French, allowed one to bring out the way in which they had deconstructed realism and Greek anthropomorphism with the help of a certain form of abstraction that is found on their coins. This deconstruction through abstraction allowed Estienne, in a dazzlingly simplistic shortcut, to connect the contemporary with the antique. The Celt was the source for the new critical abstraction that had resurfaced after centuries of slumber. The sudden irruption in Paris of this long European tradition was perceived as a major critical force, similar to the one put into place by the Celts against Greek imperialism. All one needed to do was change the names in order not only to give back to contemporary art a counterattack force but also to furnish it with an impeccable pedigree that gave Parisian abstract impressionist art a primacy over the American. This was a rather exceptional adventure for a “stain,” but one that was essential for it to be propelled to the front of the modernist stage and to the forefront of its history. This was, Estienne and Breton thought, a particularly powerful and amusing argument, even though it seemed at times a bit far-fetched. This battle seems somewhat idiotic–until, that is, one glimpses the fact that all this was being played out on a highly unstable international political stage.

Pierre Soulages, Peinture, (Painting, 196 x 270 cm, July-August 1956), 1956.

What was in fact at stake during this entire polemic was France’s position relative to political issues that, on a daily basis, involved two allies who were clashing over the most varied set of problems. It was a matter of positioning oneself at the very moment the Cold War seemed to be accelerating upon Stalin’s death and as neutralists violently opposed Atlanticists. There was also the tremendous conflict over the European Defense Council, as well as the complex negotiations with the United States following the defeat at Dien Bien Phu that were taking place just as the first bombs were exploding in Algeria. None of this encouraged one to take lightly discussions about culture. It really does seem, therefore, that Estienne and Breton were trying to carve out an independent space, one removed from American culture. The image that comes to mind is somewhat comical: Estienne standing in his little Breton sailboat facing the giant Liner on which his enemies–the aristocrat Michel Tapié de Celeyrand and the reactionary Georges Mathieu, those two characters who very much seemed to have sold their souls to the most powerful interests of the time (those of the United States)–sat enthroned. The battle was obviously lost, and Estienne knew it, as he soon afterward abandoned what he deemed to be a corrupt world of art in order to isolate himself on his boat, preferring to write popular songs for the anarchist Léo Ferré.

Oh! I almost forgot. To set all this in perspective, we must mention a postcard, found in the archives of the Getty, that was sent by the famous art critic Clement Greenberg to his mother while he was on a trip to Europe in 1939. The man who later on did so much for New York art to be welcomed into the universal pantheon, succinctly characterized the Paris scene as follows: “I’m leaving for Avignon tomorrow. I’ve already stayed in Paris too long, and Paris is not France. Among the people I’ve met have been Éluard, Sartre, Hugnet, Man Ray, Hans Arp and several others. They’re all crackpots…every one of them.” Clem.”

The die, if not already loaded, had already been cast.

Bibliography

Arnavon, Cyrille. L’Américanisme et nous. Paris: Del Duca, 1958.

Aron, Raymond. Le grand schisme. Paris: Gallimard, 1948.

Beauvoir, Simone de. L’Amérique au jour le jour. Paris: Gallimard, 1948.

Bois, Yves Alain. “Kelly en France ou l’anti-composition dans ses divers états.” Ellsworth Kelly: Les Années Françaises, 1948-1954. Paris: Galerie Nationale du Jeu de Paume, 1992.

Broschke-Davis, Ursula. Paris without Regret: James Baldwin, Kenny Clarke, Chester Himes, and Donald Byrd. Iowa City: Iowa University Press, 1986.

Campbell, James. Exiled in Paris. New York: Scribner, 1995.

Ceysson, Bernard. Ed. L’Art en Europe: Les années décisives. 1945-1953. Saint Etienne: Musée d’art moderne/Skira 1987.

Clark, Timothy J. “Jackson Pollock’s Abstraction.” Reconstructing Modernism: Art in New York, Paris, and Montreal, 1945-1964. Serge Guilbaut. Ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990.

Claustres, Annie. Hans Hartung. Les Aléas d’une réception. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2005.

Degand, Léon. “Défense de l’art abstrait.” Le Point, September 1954.

Dore, Ashton. The New York School: A Cultural Reckoning. New York: The Viking Press, 1973.

Fréchuret, Maurice. 1946. L’Art de la Reconstruction. Antibes: Musée Picasso/Skira, 1996.

Leja, Michael. Reframing Abstract Expressionism: Subjectivity and Painting in the 1940s. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

Marter, Joan. Ed. Abstract Expressionism: The International Context. Piscataway, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Mathy, Jean Philippe. Extreme Occident: French Intellectuals and America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Perry, Rachel. “Jean Fautrier’s ‘Jolie Juives.’” October, 108 (2004).

Ponge, Francis. Notes sur les “Otages.” Peintures de Fautrier. Paris: Pierre Seghers, 1946.

Ragon, Michel. J’en ai connu des équipages. Paris: JC Lattès, 1991.

_____. Vingt cinq ans d’art vivant. Tournai: Casterman, 1969.

Stovall, Tyler. Paris Noir: African Americans in the City of Light. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1996.

Wall, Irwin M. L’influence américaine sur la politique française 1945-1954. Paris: Balland, 1989.

Serge Guilbaut is an associate professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He has written on modern and contemporary art and, in particular, on cultural and political relations between the United States and France. He has published, in particular, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War (University of Chicago Press,1983; translated into 4 languages and published in French in 1990 by Éditions Jacqueline Chambon) and Voir, Ne pas Voir, Faut Voir: Essais sur la perception et la non-perception des oeuvres (Nîmes: Jacqueline Chambon, 1993). He has also edited several other works: Modernism and Modernity (Halifax, N.S.: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1983, 2006), Reconstructing Modernism: Art in New York, Paris, and Montreal, 1945-1964 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), and Voices of Fire: Art Rage, Power, and the State (on Barnett Newman; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996). Guilbaut has organized several exhibitions, as well: Théodore Géricault: The Alien Body, Tradition in Chaos in 1997, Up Against the Wall Mother Poster (on posters from 1968) in 1999, and Be-Bomb: The Transatlantic War of Images and All That Jazz, 1946-1956 at MACBA in Barcelona in 2007 (critics’ prize of the Association of Catalan Art Critics for the best exhibition of the year). He is completing a book on postwar debates in Paris entitled: Le Crachat, le Carré et l’ouvrier.