Home>An art historian at CERI.

25.11.2024

An art historian at CERI.

Interview with Androula Michael

Androula Michael is a university professor, head of international relations, and director of the Centre de recherches en arts et esthétique (CRÆ, UR 4291) at the Université de Picardie Jules Verne, as well as an exhibition curator.She has just joined us as part of a research residency hosted jointly by the Picasso Museum in Paris and Sciences Po's Centre de Recherches Internationales (CERI), made possible by the CNRS. It's a new experience, and one that we're delighted to be embarking on with Androula. Let's talk!

You've just joined CERI as part of a residency programme that enables researchers to work for a year on a project involving a collaboration between a museum and a research centre—in this case, in Paris, the Picasso Museum and CERI Sciences Po. Can you briefly outline the project you wish to focus on this year?

First of all, let me say how delighted I am to be able to carry out this joint residency at the Picasso National Museum in Paris and the CERI. In this context, and following discussions with the two institutions' directors, the project will focus on two subjects that, in a way, intersect.

The first is the critical reception of Picasso's work and personality. It is important for me today to study in greater depth the place occupied by this mythical artist not only in the field of art, but also in social debates, because Pablo Picasso has at certain periods embodied the imposing figure of the modern artist, and has been the prime target of attacks on modern art. In this respect, the current attacks on Picasso are nothing new. We need only recall Maurice de Vlaminck's incendiary criticism in Comoedia at the height of the Occupation (6 June 1942(1)), at a time when the Spanish artist was already under threat as a foreigner in France. Pablo Picasso, this “Catalan with the eyes of a monk […] is guilty of having led French painting into the deadliest impasse, into indescribable confusion. From 1900 to 1930, he led it into negation, impotence and death. For, alone with himself, Picasso is impotence made man”.(2)

Caught between criticism of modern art and criticism of foreigners for perverting the purity and clarity of French painting, Picasso has always embodied a dominant figure to be praised or opposed. It is hardly surprising, then, that he is still the focus of negative criticism, not for his works, which have become classics and whose subversive force was “forgotten” at the time of their creation—see Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) or Nature morte à la chaise cannée (1912)—but for his personality. The critical reception and the examination of the myth he embodies have preoccupied me since the beginning of my career. The symposium “Picasso. L'objet du mythe”, which I organised with Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac in 2004 at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, and the related publication, confirmed the importance of the subject.

The research I've been doing on Picasso for over thirty years now has given me the opportunity to look at and study his work in depth, concentrating initially on little-known aspects—his poetic and theatrical work—in order to gain a better understanding of his creative process. At the beginning of my career, my aim was to go beyond not only a psychologising interpretation based on his biography, but also a formalist interpretation, to penetrate further into his creative laboratory. Despite the major exhibitions that have been organised by museums and the catalogues that have accompanied them, a nuanced and in-depth understanding of Picasso's work is still the domain of researchers. After all, Picasso was and still is an extraordinary “object of myth”,(3) and there are many preconceived ideas about his work: he attacks and distorts the human figure, he martyred women, he mocked the public, to name but a few. More recently, with the #metoo movement and the publication of both noxious podcasts and far-fetched “biographies”, Picasso's figure is being challenged more than ever without his work being considered in any rigorous way. While it has previously been important to shed light on the artist's work and personality through sources, documents, and in-depth research, it is now of even greater importance to do so. To counter cookie-cutter arguments, we need to turn to the archives and put the pieces of the case into perspective and context. A significant example is the portrait of Dora Maar, La femme qui pleure, wrongly interpreted as a sign of suffering inflicted on Dora Maar by Picasso. This 1937 portrait is part of a cycle of works linked to the suffering of the Spanish people during the Civil War and Guernica, with mothers crying for their children.

The geographical areas that I am targeting for my research are Latin America (in particular Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia), about which we lack a great deal of information, as well as Africa, from the Maghreb to sub-Saharan Africa. By bringing together doctoral students and young researchers, colleagues from abroad in the academic world, and also in the field of museums, we will work to establish a mapping from a diachronic point of view, likely to be completed as the research progresses. Given the strengths of CERI and the current development of a policy of mediating social sciences and humanities research through the arts and sensibility, this mapping will be a good way of mediating and promoting the results of the research.

Apart from your work on Picasso, what other projects will you be working on as part of your residency at CERI?

The other project I'm currently working on concerns the issue of colonial slavery and its contemporary legacy in museums and the arts. This is a research project initiated with two other colleagues (Anne-Claire Faucquez from the University of Paris 8 and Renée Gosson from Bucknell University in Pennsylvania).

This research follows several earlier works that emphasise the difficulty of representing slavery without betraying this painful memory. There has been a proliferation of publications and conferences in recent years, starting with the international conference “Exposing Slavery—Methodologies and Practices” (Musée du quai Branly, 11-13 May 2011). Thirteen years on from that international conference, amidst the international mobilisation led by the Black Lives Matter movement, the explosion of global protests against racist police brutality, the desecration of statues and monuments symbolising racism, and recent calls for the decolonisation of museums, the series of conferences we organised aimed to examine how far museums have come on the issue of exhibiting and representing the colonial slave trade and slavery in European institutions.

To date, the research has focused mainly on Europe. The organisation of several conferences and workshops has resulted in a publication by Liverpool University Press.(4) A mobility grant from the Terra Foundation for the Arts and occasional support from the Maison Européenne des Sciences de l'Homme (Meshs) have enabled me to begin mapping North American museums in 2023-2024. This initial knowledge of the field now needs to be consolidated and deepened before extending the geographical scope of the project to Latin America, which will initially involve three countries, the same as those mentioned above, namely Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia.

The aim of this research, divided for the time being into distinct geographical areas in order to facilitate the study, will consist of a comparative study of museum practices, with particular emphasis on the work of contemporary artists. This is taking place in a context in which many museums are re-evaluating their institutional positioning with regard to the decolonisation of their museographic practices and the telling of national histories.

On the basis of an initial mapping phase and a preliminary comparative study of museum practices relating to the writing of the history of colonial slavery, the aim is to reflect on the methods of scientific and cultural mediation with a view to informing citizens and raising awareness among young people. For it is clear that all museography conveys a narrative through the way objects are displayed, the way rooms are organised, the way texts and labels are written, and the catalogues that are produced to accompany exhibitions. For example, the Legacy Museum, founded in 2018 by the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, explicitly links the history of colonial slavery with the recent history of the United States and the mass incarceration of Afro-descendants. This is done through a museography that makes very judicious use of historical documents and artistic proposals.

I will therefore be looking at how museums’ artistic productions can play a role in mediating and understanding complex subjects relating to history. By rewriting history in their works, while showing the links that this tragedy continues to have with our modernity, artists play a role in mediating between this memory and new generations. Fred Wilson has been a pioneering artist in raising these issues since 1992, with his artistic proposal Mining the Museum, which consisted of a new arrangement of the objects presented in the Maryland Historical Society's museum. Through unexpected confrontations of museum objects (slave chains and luxurious silver service, finely crafted chairs and a whipping post) with contemporary works of art, Wilson challenged the Western model of the museum, while revealing the silences of history.

As a contemporary art historian and exhibition curator, I have had the opportunity to work with many artists, which has enabled me to delve deeper into certain subjects linked to the question of the work of art as a means of conveying through the senses content that is more difficult to grasp solely through texts.

In concrete terms, how do you plan to collaborate with members of CERI's academic community during your stay?

Collaboration with members of the CERI's scientific community is essential for me. Several avenues of collaboration that I have discussed with Stéphanie Balme will enable me to initiate a number of synergies between the researchers and the host museum institution, as an ideal place for scientific mediation. We need to work together to think about how we can give greater prominence to an arts-based approach and encourage the co-construction of knowledge. This joint reflection will be enriched by the expertise offered by the members of the CERI research community on the different Souths (Asia, Africa, and Latin America in particular), as well as by my own experience in the field of art and museums. I would like us to work together to set up collaborations based on innovative and less conventional formats than those usually used in research work, in particular the sensitive cartography mentioned above.

In addition, I would like to consider CERI seminars such as the reading seminar or “Retour de terrains” as places where knowledge and know-how can be shared between the different disciplines mentioned. The CERI seminar on postcolonial approaches could also be a place for stimulating discussions around the readings already initiated that are renewing Picasso's work.

In any case, I hope that this residency will give rise to stimulating forms of research mediation that are open to the community, within a structure that is engaged with the wider community, where knowledge and thought intersect between the humanities and the social sciences.

Finally, I would very much like to be able to interact with the CERI's scientific community in order to compare and contrast working practices and methodologies. In this context, I could imagine setting up a seminar on the issue of scientific mediation through the arts, which I think would be stimulating for everyone involved. I also like to imagine that things that I hadn't thought of might come up and open up new avenues of thought. Because I firmly believe that the unexpected can be a rich source of potential.

As well as being an art historian, you also curate exhibitions. You've just opened a curated exhibition of works by Barthélémy Toguo at the Frac (Fonds régional d'art contemporain) in Amiens. Can you tell us a bit about it?

The Barthélémy Toguo exhibition “Ceci est le dessin de mes rêves” (This is the drawing of my dreams) currently on show at the Frac Picardie is a continuation of a close and long-standing collaboration with the artist. His multi-faceted work touches directly on subjects that concern me as an art historian.

He is a contemporary artist who handles all media with great talent, and has a highly stimulating approach to art that is in tune with society, history, and memory. His work is very stimulating for my research into colonial slavery and its contemporary legacy in the arts and museums. I have already staged a number of exhibitions in collaboration with Barthélémy, including the group show Retours à l'Afrique at Bandjoun Station in Cameroon and the individual exhibitions Habiter la terre at Hab Galerie in Nantes, Picasso/Toguo at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, and Stronger Together, which is currently on show at the Mohammed VI Museum in Rabat, Morocco.

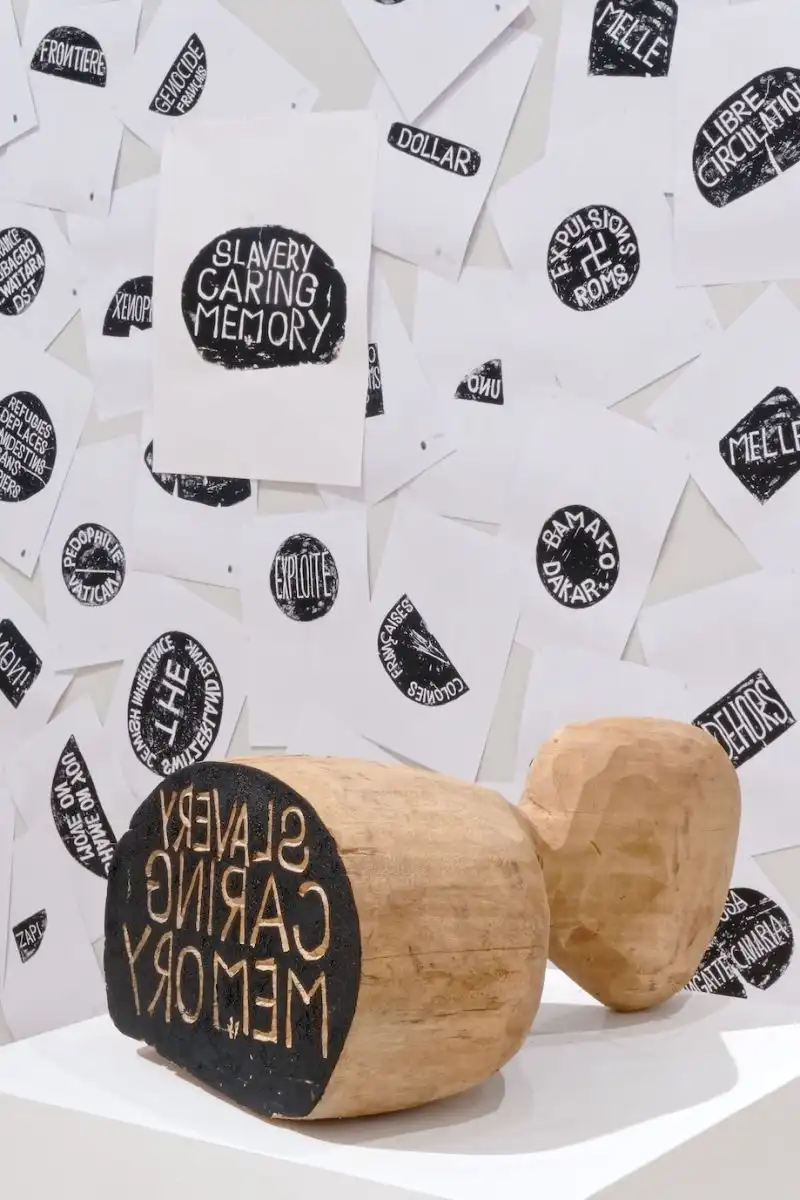

The current exhibition at the Frac Picardie, which focuses on drawing, mainly comprises works on paper (two series of drawings , Das bett and Animal Comedy), accompanied by a number of sculptures, including Le Christ de la Cathédrale Notre Dame d'Amiens, dating from the time—over thirty years ago—when the artist was studying at the Abidjan School of Fine Arts. The exhibition is completed by a large ink drawing, 10 metres wide and 1.5 metres high, produced in Egypt, Les Pleureuses . Without copying Egyptian iconography, he traverses history and condenses in his mind all the scenes of mourning and crying, feelings that humans share. Crying and prayers become a cry against all forms of social injustice, discrimination, and the over-exploitation of nature. Here, the artist turns the melancholy dimension of a fateful scene into a profound desire for life. Finally, the exhibition presents the artist's emblematic work Urban Requiem (2015-2024), consisting of a display of footprints and a giant bust-shaped stamp with the engraved inscription “slavery caring memory”. This echoes the sculpture dedicated to the memory of colonial slavery that will be inaugurated on 10 May 2025 in a park (Square Aimé Césaire) in Amiens.

The exhibition is rounded off by a presentation of Bandjoun Station (an art centre, museum, and artists' residence, with an ecological project that is unprecedented on the continent). I've been to this fascinating place twice—to organise a conference and an exhibition (Retours à l'Afrique)—and it has both an artistic and a social dimension.

Do you see curating as research?

I see curating as a research project that stems from and extends my academic work. For an art historian, there's nothing more exciting than to see works placed in a space, interacting with each other and constructing anarrative.

It's also collective work, which I particularly enjoy—I've organised or co-organised several exhibitions on subjects ranging from Picasso's Cuisine and Picasso the Poet to contemporary art (Retours à l'Afrique). Curating exhibitions is research in action; for me, it's an excellent way of mediating science and promoting research to a wider audience. It's also an activity that can't be done without collaboration and interaction with people from a wide range of professions, which adds to the pleasure of sharing experiences in pursuit of a common goal.

Finally, you are one of the co-founders of the “Doctorat Picasso”, a higher education programme that is part of an agreement between the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, the Université de Picardie, Jules Verne (Amiens), and the Museu Picasso in Barcelona. What does this project involve?

The “Doctorat Picasso” is a unique academic programme at the international level co-founded by Emmanuel Guigon (Picasso Museum, Barcelona), Jèssica Jaques (Autonomous University of Barcelona), and myself (Université de Picardie Jules Verne). It offers post-graduate students high-level teaching by lecturers, museum directors, curators, and archivists, as well as artists and personalities from the world of culture in general, such as the great Catalan chef Ferran Adria, who have been invited as guest lecturers and are known for their expertise in the field. The aim of the Doctorat Picasso is to strengthen research about Picasso, and to examine the artist and his work in the light of the present, without falling into anachronism. Its aim is to put things into context, to shed light on them using sources and documents, and to open up new research perspectives.

The way in which the artist—whose work and personality continue to provoke lively debate in society—is received, deserves to be examined in a new light. Annual seminars have been held on subjects most often related to exhibitions that are the results of research or linked to important contemporary issues affecting Picasso's work. I could mention, by way of example: Still life and the presence of food in Picasso's writings (in conjunction with the exhibition Picasso's Cuisine, of which I was co-curator); Picasso the Poet and, more generally, Picasso's relationship with poets (in conjunction with the exhibition Picasso le poète , of which I was also co-curator); and “Gynocentric” readings of Picasso's work (in conjunction with the exhibition on Lola Picasso, the artist's sister). During these sessions, leading figures from a variety of disciplines (museum curators, anthropologists, sociologists, etc.) were invited to respond to a topical issue aimed at revisiting art history from the point of view of gender issues for example. In addition to the seminar sessions, colloquia and meetings have also been organised. See, for example, the international symposium on “Picasso, un poète qui a mal tourné” (Picasso, a poet gone wrong) or the meeting with Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac, organised jointly by the Doctorat Picasso and the MCTM group on “Picasso au croisement d'un réseau d'amitiés. Regards sur les problématiques anti/post/coloniales”. The seminar for the 2023-2024 academic year on Picasso and Catalonia adopted a nomadic mode and was held in places that are important for the study of Picasso's work: Barcelona, Madrid, Horta de Ebro, Gosol, Paris, and Cadaqués. This year, which marks the centenary of the publication of André Breton's Manifesto of Surrealism, the seminar will focus on Picasso and Surrealism.

Interview by Miriam Périer

Cover photo: Portrait of Androula Michael by Ilaf Haïdar

Photo 2: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Museum of Modern Art de New York. Photo by Bumble Dee for Shutterstock

Photo 3: Poster of the conference Exposer l'esclavage, at the Musée du Quai Branly

Photo 4: Banjoun station, West Cameroun. Copyright: Bandjoun Station and Barthélémy Toguo

Photo 5: Photo of Barthélémy Togo's exhibition (Ceci est le dessin de mes rêves) at FRAC Amiens, by Irwin Leuillier

Photo 6: Poster of the exhibition Ceci est le dessin de mes rêves, Barthélémy Toguo, at FRAC Amiens.

Photo 7: Entry of the Picasso museum in Barcelona, May 2024. Photo by Irina Brester for Shutterstock

Notes

- 1.Maurice de Vlaminck, ‘Opinions libres sur la peinture’, Comoedia, 6 June 1942.

- 2.Ibid.

- 3.Title of the symposium Picasso, L'objet du mythe, organised with Laurence Bertrand-Dorléac at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris, 29-30 November 2002, the proceedings of which were published by the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in 2005.

- 4.Anne-Claire Faucquez, Renée Gosson, Androula Michael (eds.), Narrativizing Slavery in European Museums: Arts and Representations, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press (forthcoming 2025).

(credits: Ilaf Haïdar)

Follow us

Contact us

Media Contact

Coralie Meyer

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 85

coralie.meyer@sciencespo.fr

Corinne Deloy

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 68

corinne.deloy@sciencespo.fr