Critique Internationale Editorial. Freedom for Fariba Adelkhah

25 January 2021. It has been almost two years now that Fariba Adelkhah has been deprived of her freedom. More precisely, 600 days ago today, she was arrested in Iran, with our colleague Roland Marchal, who has since then been released.1 From June 2019 to September 2020, she spent almost 16 months in Evin Prison. Since then, she has been under house arrest, with an electronic bracelet and without the possibility of contacting the outside world. Her face is now familiar to people who never had the chance to meet her before. Her portrait adorns the façade of Sciences Po, rue Saint Guillaume in Paris, it is displayed on every door at the CERI, and her photo and name are part of the electronic signature of part of our community. Since 5 June 2019, her support committee has been acting never-endingly by intervening in the media, co-organising a conference in January 2020 that produced a book,2 recording messages for her and for the world, innovating in the midst of circumstances and constraints imposed by the pandemic.

25 January 2021. It has been almost two years now that Fariba Adelkhah has been deprived of her freedom. More precisely, 600 days ago today, she was arrested in Iran, with our colleague Roland Marchal, who has since then been released.1 From June 2019 to September 2020, she spent almost 16 months in Evin Prison. Since then, she has been under house arrest, with an electronic bracelet and without the possibility of contacting the outside world. Her face is now familiar to people who never had the chance to meet her before. Her portrait adorns the façade of Sciences Po, rue Saint Guillaume in Paris, it is displayed on every door at the CERI, and her photo and name are part of the electronic signature of part of our community. Since 5 June 2019, her support committee has been acting never-endingly by intervening in the media, co-organising a conference in January 2020 that produced a book,2 recording messages for her and for the world, innovating in the midst of circumstances and constraints imposed by the pandemic.

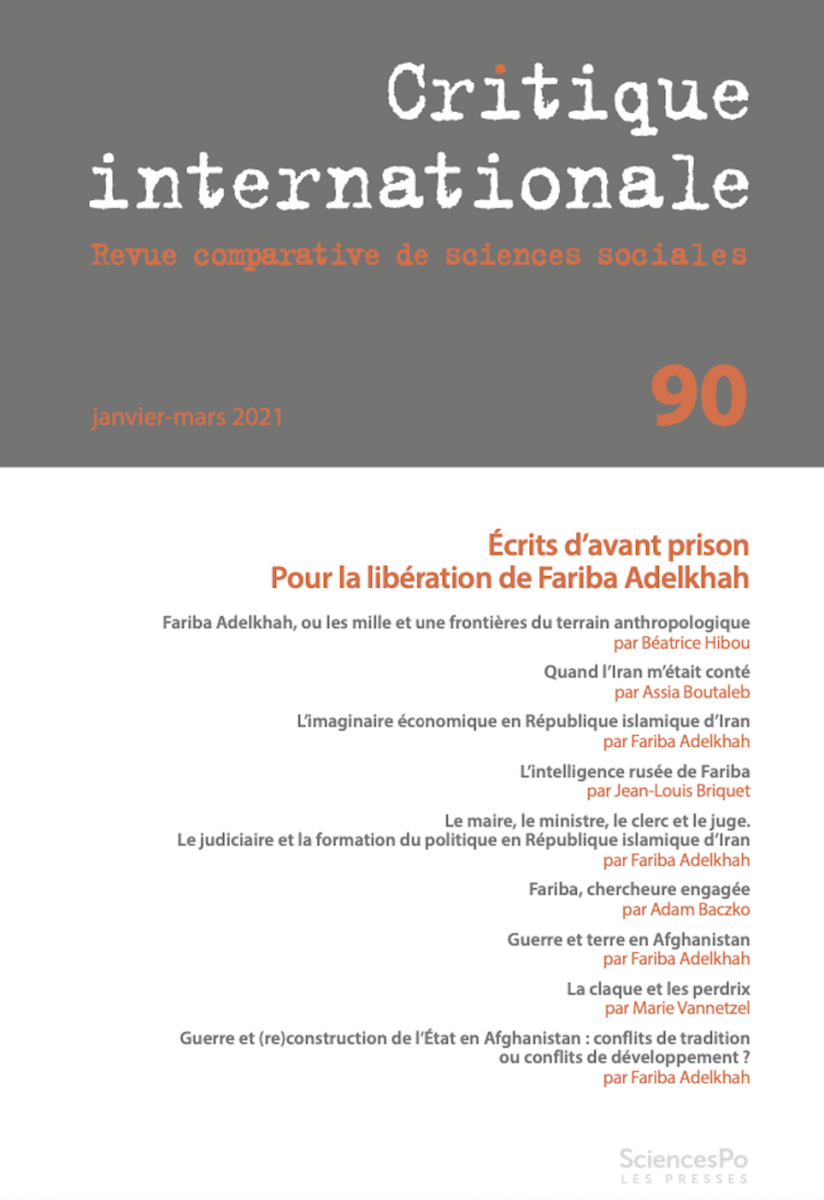

In collaboration with the support committee, Critique internationale, of which Fariba was a founding member in 1998, wishes to pay tribute to her work, her courage, and her commitment. Entitled “Writing Before Prison: For the Release of Fariba Adelkhah”, this special issue gathers together four of her texts that have already been published and for which we thank the publishers and the journals for their kind permission to republish here. These “selected works” from her long-lasting research make a singular voice heard, supported by an original way of thinking that rests on an acute empirical knowledge of the phenomena under study, an attention given to historical processes, and a fertile dialogue between anthropology and political science.

Beyond a mere testimony, our decision to publish this volume is also an invitation. To read or re-read Fariba Adelkhah is to support her. To quote her is to make her exist. To discuss her work is to think with her,3 despite the silence imposed by her house arrest and the fact that it is forbidden for her to be in touch with colleagues. It also means understanding a methodological stance based on fieldwork, as Béatrice Hibou analyses in her introduction to this issue.4

The contributions that we have gathered here witness the ways in which Fariba has influenced, inflected, and sometimes shaken up the questionings of several generations of researchers working in fields that were not all focused on Iran and Afghanistan. Four of these scholars pay tribute to Fariba Adelkhah’s work today by introducing each article that we republish in this issue.

Assia Boutaleb remembers how Fariba introduced her to the “fertile eclecticism of collecting research material”, marking her very first steps as a researcher. To present the article “L’imaginaire économique en République islamique d’Iran” (The Economic Imaginary in the Islamic Republic of Iran),5 Assia Boutaleb recalls the way Fariba explores the figures of economic success through the example of Ali, a Mercedes seller in the Islamic Republic of Iran, and Teyyed, chief of a fruits and vegetables market in Tehran in the time of the Shah—all the while in dialogue with Mauss and Weber.

Jean-Louis Briquet, a long-time intellectual accomplice of Fariba, talks about a “provocative paradox [...], a sharp tool of an interpretative approach” to describe his colleague’s analysis of the judicial system used by the conservative factions of the elites of the Islamic Republic as a weapon against their reformer opponents. In “Le maire, le ministre, le clerc et le juge. Le judiciaire et la formation du politique en République islamique d’Iran” (The Mayor, the Minister, the Clerk and the Judge: The Judiciary and the Formation of the Political in the Islamic Republic of Iran),6 Fariba’s description of the games of power and influence that led to the arrest and condemnation of the Mayor of Tehran at the end of the 1990s is painfully topical.

Fariba also marked Adam Baczko’s first steps as a PhD student. Adam joined the CERI in October 2019 while Fariba was in prison. He recalls the conference she had organised in 2012 at the CERI in which she had invited him to participate, as well as the publication that followed, in an issue of the journal Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée in which Adam published one of his first articles thanks to Fariba. In particular, he mentions the founding discussions they had on the importance of the issue of property in Afghanistan during the war and recalls that in her article “Guerre et terre en Afghanistan” (War and Land in Afghanistan),7 she insisted on the fact that “against the biases and shortcomings of dominant analyses, the appropriation of property and related uncertainty were a major concern of Afghani peoples”.

Finally, Marie Vannetzel expresses the shock she felt while listening to Fariba read the first part of her draft paper, entitled at the time “L’aide internationale et les perdrix. Les effets pervers de l’idée de développement en Afghanistan” (International Aid and the Partridges: The Negative Effects of the Idea of Development in Afghanistan).8 This reading took place at a workshop during which several scholars had gathered to prepare a special issue of the journal Revue internationale de politique de développement/International Development Policy. Marie Vannetzel, CNRS researcher, was no “partridge”, but Fariba’s text had a “strong charge” that stunned her. In the final version of her article (“Guerre et (re)construction de l’État en Afghanistan : conflits de tradition ou conflits de développement ?”—“War and State (Re)Construction in Afghanistan: Conflicts of Tradition or Conflicts of Development?”),9 Fariba denounces the reifying conceptions of ethnicity that orient international funding, as well as the wish to “fix” populations whose survival rests on mobility.

This special issue is wholeheartedly dedicated to her. It is a call for her unconditional liberation. It is also a call for us not to forget: the men and women who are detained in Iranian or Turkish jails for their freedom of thought; all those who have lost their lives while doing their job, such as Giulio Regeni, a PhD student working on Egypt; all those who have been deprived of their right to teach, such as Academics for Peace in Turkey; and all those whose institutions have been closed or whose disciplines have been threatened during recent years.

Two “Varia” articles are also published in this issue. They reveal original facets of the French presence in West Africa. Léonard Colomba-Petteng does this in a way seldom used in political science since he sheds light on the effects of the usage of the French language in EU representation services in the city of Niamey, in particular in the framework of the European Union Capacity Building Mission in Niger (EUCAP Sahel). In an equally original way, in the analysis of armed conflicts, Denis Tull focusses on rumours, conspiracy theories and other unconfirmed information as forms of protest against the French intervention in Mali since 2013.

Critique Internationale editorial committee

This editorial was published online with the permission of Critique Internationale's publisher, les Presses de Sciences Po. English version by Miriam Perier and Caitlin Gordon Walker.

- Visit Critique Internationale's webpage

- Read the introduction to this special issue, by Béatrice Hibou

- Access the journal on Cairn

- Support to Fariba on the CERI's website

- Support Committee

- Twitter Free Fariba Adelkhah

- Facebook page for Fariba Adelkhah and Roland Marchal Support committee

- Bibliography (scroll down)

- 1. Roland Marchal was released on 20 March 2020. See the website of the Fonds d’analyse des sociétés politiques (FASOPO)

- 2. Pour Fariba Adelkhah et Roland Marchal. Chercheurs en périls, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2020.

- 3. See the sessions of the seminar “Sociologie et anthropologie sociale du politique”, the subtitle of which is “Penser en pensant à eux” (Think while thinking of them).

- 4. Béatrice Hibou, “Fariba Adelkhah, ou les mille et une frontières du terrain anthropologique”, Critique internationale, 90, 2021, p. 11-20.

- 5. Initially published in Jean-François Bayart (ed.), La réinvention du capitalisme, Paris, Karthala, 1994, p. 117-144.

- 6. Initially published in Philippe Garraud, Jean-Louis Briquet (eds.), Juger la politique. Entreprises et entrepreneurs critiques de la politique, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2002, p. 123-137.

- 7. Initially published in Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée, n° 133, June 2013, p. 19-41.

- 8. Note from the translator: In Afghanistan, partridges are bred to fight. Partridge fights are a much-appreciated spectacle.

- 9. Initially published in Revue internationale de politique de développement/International Development Policy, n° 8, 2017, https://doi.org/10.4000/poldev.2451