New dynamics of political integration

12 March 2016

To be Represented at the International Labour Organisation

20 May 2016Paul-André Rosental, university professor at Sciences Po’s Centre for History, and associate researcher at the French National Institute for Demographic Studies (INED), devotes his research to the social and political history of populations, that is, to the policies, practices and knowledge of demography, health and social protection.

Paul-André Rosental’s research on the social rights that have benefitted migrants (or not) over the past century, sheds light on many current issues in this area. He notably observes that the two opposing forces we are currently experiencing – integration and rejection policies – have always mixed, and even defined themselves in relation to the other.

The “tyranny of the national”

The “tyranny of the national”

Paul-André Rosental particularly underscores the importance of the turning point at the end of the 19th century. Assistance to migrants ceased to be addressed at the municipal level and became the responsibility of states. This period is often considered to mark the advent of a “tyranny of the national” ending an era of freedom of movement. However, in reality the transformation was of a different nature. The “nationalization” of protection granted to the poor, and the shift from a regime of discretionary assistance to a system focused on the notion of social rights changed the regulation of international mobility. Previously conducted ex-post (immigrants who failed to economically integrate were considered to be expellable), it started to be applied ex-ante: the border controls characterizing our contemporary regime became preeminent. From the perspective of social rights, this selection upon entry set migrants thus accepted on “a path towards the more complete assimilation of foreigners with nationals”, as a legal expert put it around 1900.

Shared progress

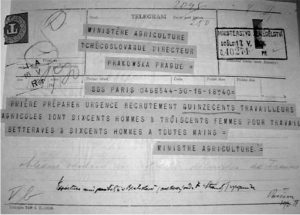

The “reform cluster” ensured the transnational dissemination of this mechanism at the beginning of the 20th century. The idea was not only to grant foreigners rights, but also to use work-related immigration to extend social insurance protections to all employees. The International Labour Office endorsed this policy during the interwar period, paving the way for the social security regimes we know today.

At the mercy of events

The terms of this process was constantly reworked by the economic and political contexts of the moment. The application of the law fluctuated over time, depending on labour needs and the intensity of nationalist sentiments. The protection that countries of origin attempted (or not) to provide to their emigrant citizens also constantly changed, according to considerations linked to the state of the labour market as well as their professional qualifications and their membership in ethnic groups deemed more or less desirable….

Despite these erratic developments at the national level, international laws aiming to protect migrants have tended to strengthen over time. Depending on local power relations, these laws have sometimes served as a last resort for migrants. Thus, the barriers placed at the entry of the territory are the expression of both the “tyranny” and weakening of the national.

-

Next article: On the road again

-

Previous article: New dynamics of political integration

Bibliography

- National citizenship and migrants’ social rights in twentieth-century Europe, postface in Steven King et Anne Winter (eds.), Migration, Settlement and Belonging in Europe, 1500s-1930s. Comparative perspectives, Berghahn Press, New York & Oxford, 2013

- Migrations de travail et droits sociaux de l’Europe de 1900 à la Chine d’aujourd’hui, Entretien croisé avec Chloé Froissart par Nicolas Delalande et Ivan Jablonka, in La Vie des Idées, 2012

- Migrations, souveraineté, droits sociaux. Protéger et expulser les étrangers en Europe du XIXe siècle à nos jours, in Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales, 2011