Estelle Bories, who wrote her dissertation at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) on contemporary Chinese art, reexamines for us the historical context within which this issue emerged. She is interested in the origins of the Chinese avant-garde, in the Woodcut Movement, and in the internationalist standpoint adopted by the writer Lu Xun in the 1930s, all of this with a concern to understand the questions of artistic references and equality that have been posed from that time until today.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Hartung-Bergman Foundation Seminar, June 2012

Different Aspects of the Passion for Equality in Chinese Modern and Contemporary Art

Estelle Bories

The issue of equality in Chinese modern and contemporary art is often associated with the reversal in the relation of force that had made of modernity merely a matter of the Westernization of the world. Recently, the Swiss collector of Chinese contemporary art, Uli Sigg, made known that he was bequeathing nearly 1,500 works to the future Hong Kong M+ Museum. The goal for the erection of this large-scale museum structure, which would like to be the equal of MoMA, is to offer places of equal importance to Chinese and Western avant-garde movements and to establish thereby a new historiographical understanding.

http://leapleapleap.com/2010/12/woodcuts-in-modern-china-1937-2008/

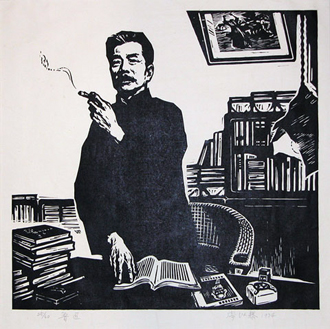

Song Guangxun, Brave chinese women (portrait of Lu Xun), 1974, woodcut printed with oilbased ink, 43,2×54,3cm.

In order to comprehend this movement, we must reexamine what Xiaobing Tang calls the “origins of the Chinese avant-garde,” that is, the modern Woodcut Movement, and the internationalist standpoint adopted by the writer and essayist Lu Xun in the 1930s [ref]Xiaobing Tang, Origins of the Chinese Avant-Garde: The Modern Woodcut Movement (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000).[/ref]. Reflection around the issue of the internationalization of artistic references was to be of major importance throughout the twentieth century and also conditioned discussions around the issue of equality. Two contemporary artists living in exile (Huang Yong-Ping and Cai Guo-Qiang) have overcome the sense of a time-lag and inequality vis-à-vis Western avant-garde movements by replaying the Taoist connection with the Dada movement, in the case of the first of these two artists, and by working out a structural process of cultural differentiation, in the case of the second.

Lu Xun and the Woodcut Movement: Consciousness-Raising about Inequalities

http://www.spencerart.ku.edu/exhibitions/radicalism/liyitai.shtml

Li Yitai, Marxism is the Most Lucid and Lively Philosophy, Portrait of Lu Xun, 1974, woodcut, oil based ink on Chinese paper, Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas.

The writer and essayist Lu Xun remains a reference that cannot be ignored in the historiography of Chinese modern and contemporary art [ref]Lu Xun (1881-1936), who was born in Zhejiang, came from a family of teachers affiliated with the Qing Dynasty that suffered disgrace at the end of that dynasty’s reign. Despite the fact that he had pursued the study of medicine during his stay in Japan, in 1902 he turned instead toward literature. Upon his return from Japan, he occupied various educational posts (this was the era of institutional reform spearheaded by Cai Yuanpei) and he became involved in the May Fourth 1919 Movement. He arrived in Shanghai in 1927 and joined in with the creative efforts of the League of Left-Wing Writers (Zhongguo zuoyi zuojia lianmeng). In addition to his work as a translator, teacher, writer, and essayist, Lu Xun published a number of journals. One of the episodes that was to mark a break between Lu Xun and the Chinese Communist Party unfolded near the end of his life. Following the Japanese invasion, the Chinese Communist Party wanted to establish a united front in line with the directives of the Comintern. Under the leadership of Wang Ming and Zhou Yang, who were in charge of the culture sector, Party cadres desired a united front that would develop literature oriented toward national defense. Lu Xun and his comrades from the League of Left-Wing Writers were opposed to decisions heading in the direction of ideological uniformization. As a result of various ploys orchestrated by Zhou Yang (vigorously criticized by Lu Xun), the League of Left-Wing Writers was dissolved. Some of Lu Xun’s followers were targeted for repression.[/ref]. A key figure in the development of modernity in the early twentieth century, he was celebrated by President Mao as an emblem of art’s engagement with society [ref]Bonnie S. McDougall, “Introduction: The Yan’an ‘Talks’ as Literary Theory,” in Bonnie S. McDougall, trans., Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art” (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan, 1980).[/ref]. Yet such utilization was not onesided: rehabilitation of some of Lu Xun’s fellow travelers coincided with denunciation of the excesses of Maoism subsequent to the Great Helmsman’s demise in 1976 [ref]Chang-Tai Hung, “Two Images of Socialism: Woodcuts in Chinese Communist Politics,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 39:1 (January1997): 34-60.[/ref].

Though he had not himself joined the Chinese Communist Party (which was created in 1922), Lu Xun did remain associated with the history of the 1930s Shanghai Left [ref]The League of Left-Wing Writers joined the Communists.[/ref]. The development of such themes as struggle against oppression and revival of the graphic arts, as made possible by woodcuts (through their dramatization effects), formed the structural backbone of the formalist revival theorized by Lu Xun.

The objective at the time was less to impose a new phase of cultural harmonization than to scrutinize problematic features. While Lu Xun strove to promote the prestige of the Chinese roots of woodcut engravings (zhongguo banhua)—a technique that had been practiced as early as the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and which had its hour of glory under the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)—he also underscored the importance of the role of engravers from Germany (Käthe Kolwitz, Carl Meffert), Belgium (Frans Masereel), America (William Siegel), Russia (Aleksandr Serafimovich) and Japan (Uchiyama Kakechi) who, in his view, reconciled Social Realism and Expressionism [ref]In addition to engravers, Lu Xun’s reference to the paintings of Constantin Meunier (1831-1905) attests to his interest in the figures of activist artists. See Huang Mengtian, Lu Xun yu meishu (Lu Xun and the Fine Arts) (Daguang Chubanshe, 1972). Of a cosmopolitan turn of mind, Lu Xun also collected Japanese engravings and, more particularly, creative prints (Sosahu hanga). He did not overlook New Year’s woodcut engravings—viewed as symbols of prosperity and luck (nianhua)—which were still present in rural areas. Starting in 1933, Lu Xun became interested in Soviet engraving. He organized, among others, some exhibitions in vacant apartments. See, on this point, Xiaobing Tang, Origins of the Chinese Avant-Garde.[/ref]. For Lu Xun, the revival of woodcut engraving in China was part of an international artistic phenomenon based on the involvement of left-wing artists [ref]Let us recall, in this connection, that Lu Xun went to the German consulate of Shanghai on May 13, 1933 to protest against the violence of the Chinese government. See Xiaobing Tang, Origins of the Chinese Avant-Garde.[/ref]. This undoubtedly was one of the salient features in the development of woodcut engraving in the early 1930s in China as well as the key to its critical success: without breaking with the country’s national heritage, woodcut engraving allowed one to fit a portion of Chinese art into a movement whose goal was to expose various forms of inequality [ref]Li Hua wrote a text entitled “The Influence of Emotion: A Few Experiments in the Teaching of the Art of Kollwitz.”[/ref]. This undoubtedly was one of the salient features in the development of woodcut engraving in the early 1930s in China as well as the key to its critical success: without breaking with the country’s national heritage, woodcut engraving allowed one to fit a portion of Chinese art into a movement whose goal was to expose various forms of inequality [ref]Julia F. Andrew and Kuiyi Shen, eds., A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998).[/ref]. As opposed to the well-known, highly-polished images of Shanghai advertising posters, which were a reflection of the embourgeoisement and Westernization of the urban lifestyle, woodcut engraving, with its roughhewn technique, gave eloquent expression to the scars of injustice [ref]The period during which Lu Xun was living in Shanghai coincides with that of the various purges of which the Communists were victim as Chiang Kai-shek came to exercise control over the National Party (Kuomintang). Chang’s desire to prevent the Communists from taking control of the Party led him to organize massacres and violent attacks in the factories, in 1927.[/ref]. Among the themes of the woodcut engravings produced in Shanghai in the early 1930s were repression in the working-class world (Jiang Feng), protest against Japanese bombardments and then against the Japanese invasion of 1937 (Liu Xian, Hu Yichuan), and exhaustion at work (Chen Baozhen). Always more in phase with an internationalist view of the proletarian struggle, Lu Xun supplied information about woodcut engraving outside China [ref]The writer Rou Shi, who was close to Lu Xun, was also very active in the search for new references that would boost art’s impact in revolutionary struggles.[/ref]. And yet, this exploratory phase was to prove rather ineffective in the effort to raise the consciousness of the popular classes [ref]Francesca Dal Lago, “Les racines populaires de l’art de la propagande communiste en Chine: des gravures sur bois du Mouvement pour la nouvelle xylographie aux nouvelles estampes du nouvel an,” Art Asiatique, January 2012.[/ref].

After Lu Xun’s death, the Woodcut Movement was to take part in the development, at Yan’an, of a form of revolutionary art that disowned the critical legacy handed down by this writer [ref]The 1942 Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art set the foundation for the major artistic orientations to come. During the episode of the Long March, Yan’an was to be the Communists’ main base of operations after the retreat in 1934 from the Jiangxi Soviet (zhonghua suweiai gongheguo), which initiated the Long March. It was also at Yan’an that the first direct attacks on intellectuals occurred. See, on these issues, Mao Zedong, “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” in Selected Works, vol. 3 (Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1967); David E. Apter, “Le discours comme pouvoir: Yan’an et la révolution chinoise,” Cultures & Conflits, 13-14 (Spring-Summer 1994), http://conflits.revues.org/index205.html (English-language version: “Discourse as Power: Yan’an and the Chinese Revolution,” New Perspectives on the Chinese Revolution, Tony Saich and Hans can de Ven, eds. [New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1995], pp. 193-234). See also Merle Goldman, China’s Intellectuals: Advise and Dissident (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981).[/ref]. References to left-wing artistic personalities then gave way to an emphasis on the popular national heritage and to Socialist Realism. The dead end of woodcut engraving could be said to be attributable to its inability to find a popular base. The modernization of Chinese art had ultimately led to a clear-cut demarcation between, on the one hand, a formalist revival, and, on the other, the championing of a kind of art that would highlight its social calling and its capacity to be understood by the great majority of the people.

Historiographical Rectifications and Passions for Equality

In several of his writings, the art historian Gao Minglu states that, contrary to the Western avant-garde and its “bohemian bourgeois” sometimes described in a rather caricatural manner, the Chinese avant-garde is not an aesthetic avant-garde [ref]Gao Minglu, Zhongguo dangdai meishushi, 1985-1986 (Contemporary Chinese art) (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Press, 1991); Gao Minglu, Zhongguo dangdai meishu yanjiu xilie: Zhongguo qianwei yishu (A series of investigations into Chinese contemporary art: the avant-garde in China) (Nanjing: Jiangsu Meishuchubanshe, 1997); Gao Minglu, Total Modernity and the Avant-Garde in Twentieth-Century Chinese Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011).[/ref].

Chinese-style Socialist Realism had cast a smokescreen over the abundant discussions about modernity, which previously had been judged solely from the perspective of Western contributions. Experiments undertaken on the basis of elements to be found in Chinese culture were more fecund than the attempts to use foreign forms in order to reflect the changing nature of Chinese society [ref]In an article, Ralph Croizier analyzes changes in the historiography of Chinese modern and contemporary art: “Art and Society in Modern China–A Review Article,” The Journal of Asian Studies, 49:3 (August 1990): 586-602.[/ref]. Both in its technical aspects (introduction of oil painting) and in its artistic ones (academic Realism, familiarity with Western avant-garde movements), influences coming from Western art did not in fact end up having the hoped-for effects.

Huang Yong-Ping and Referential Distortion:

Dada, Duchamp, Fluxus, the Tao, and Chan Buddhism

Huang Yong-Ping :

http://visualarts.walkerart.org/oracles/details.wac?id=2265&title=Works

While this current of referential readjustment did indeed develop during the first half of the twentieth century, what was going to reignite the question of how to go beyond historical Western avant-garde movements was the birth, in China, of an artistic new wave (xin chao) between 1985 and 1989. The introduction of the Dada movement in the 1980s is viewed by numerous art historians as the detonator for a phase of formalist experiments that was unprecedented in that country [ref]Fei Dawei, ’85 xinchao: Zhongguo diyici dangdai yishu yundong (’85 New Wave: The Birth of Chinese Contemporary Art), Ullens Center for Contemporary Art exhibition catalogue in Chinese and English (Shanghai: Century Group, 2007).[/ref].

Such direct descent is clearly proclaimed by Huang Yong-Ping, one of the major artists of the New Wave of 1985 [ref]Huang Yong-Ping often emphasizes the quite fragmentary character of his knowledge of Western avant-garde movements. He has said that he knew of John Cage through the translation of Peter S. Hansen’s encyclopedia, An Introduction to Twentieth Century Music. Concerning Rauschenberg, an exhibition of the American artist’s work, part of his Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange (ROCI) project, took place in 1985 in Peking at the National Gallery, which accelerated the spread of knowledge about the artist’s work through China. Huang Yong-Ping has also said that he knew of the work of Marcel Duchamp through a bad Chinese translation of a book of interviews.[/ref]. In one of the founding texts of this movement, he mentions the importance of the development of the Dada spirit in China, while not necessarily referring to Dadaist works. In this sense, he demonstrates a tenacious will to transcend national limits and examine the legacy of the Dadaist and Fluxus international. His series around the theme of roulette wheels (“zhuanpan xilie”), from 1985, served as the occasion to employ a Chinese geomancy disk inspired by the Book of Changes (I Ching) while invoking, at the same time, the work of Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, and Robert Rauschenberg. Thus, a passageway between Chinese thought and Western thought can be posited while working out a viewpoint that turns away from any sort of organizing principle for the world that would be ruled by infallible faculties of judgment.

Rauschenberg’s use of whatever elements he came across and his juxtaposing of diverse objects in his painting are very much in tune with Taoism’s ideas of the equality, sameness, and coexistence of everything. Marcel Duchamp comes closer to Laozi’s concept of “hiding one’s brilliance, appearing dull,” and to his contemplation and wisdom of life, than any modern Asian. [ref]Huang Yong-Ping, “Xiamendada Postmodern,” House of Oracle (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2005), p. 75.[/ref]

Huang Yong-Ping never entered into a relationship of otherness. On the contrary, he was able to spot similarities in approaches that led to experiments with contingency.

Cai Guo-Qiang and the Affirmation of Cultural Superiority

Cai Guo-Qiang : studio à New York pour la demande de reproduction.

http://www.caiguoqiang.com/projects/borrowing-your-enemys-arrows-1998-new-york-ny-usa

References to the fundamental works of Chinese culture also constitute the basis for the worldview developed by Cai Guo-Qiang. An exile living in the United States, he is often perceived as the most eminent representative of a globalized form of art [ref]Cai Guo-Qiang was born in 1957 in Quanzhou, in Fujian Province. He himself came from a family of men of letters. His father was a traditional scroll painter. He studied design at the Shanghai Drama Institute from 1981 to 1985. He left China to live in Japan in 1986 and arrived in the United States in 1995. He first became known for his works that employed explosives.[/ref]. What he proclaims, however, is the loss of Western influence and the importance of a cultural continuity that guides the evolution of Chinese art. According to him, his art is not tied up with some new formalist state but refers more to the re-creation of a preexisting world.

Western art critics can locate my work in their “bottleneck” and of course they can explain it by means of whatever “participative aesthetics” they want. But maybe these issues have nothing to do with our history of art. In that case, we can completely ignore this point of view [ref]Fei Dawei, Cai Guo-Qiang (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000), n.p.[/ref]

Known for his works that employ explosives (cannon powder, which, let us recall, is a Chinese invention), he later turned toward the execution of imposing installations that introduce key symbols of Chinese culture.

In an installation entitled Borrowing Your Enemy’s Arrows, he presents the shell of a fishing boat shot through with arrows. The reference to Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo Zhi) is obvious. Low on projectiles, General Zhuge Liang fooled the enemy by sending off an empty boat. The opposing army, thinking it would assert its military superiority, fired a salvo of arrows that eventually went to replenish the reserves of its adversary. For Cai Guo-Qiang, the reversal of forces, symbolized in this installation, shows two antithetical ways of envisaging adversity: from the Western side (the shooters of arrows), a brutal confrontation, and, on the Chinese side (the transpierced shell), a subtle approach that ends up overturning the aggressive relationship in place [ref]“To describe it in basic terms, in Western boxing if the opponent is hit in the face hard enough he falls, so it’s easy to decide who’s won. In Chinese martial arts it’s much more complex, more internal. The exchanges are more subtle, often using the opponent’s own force to defeat him,” Sheldon H. Lu, Chinese Modernity and Global Biopolitics: Studies in Literature and Visual Culture (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2007), p.102.[/ref]. The presence of the Chinese flag, placed within the small craft, accentuates the resolutely ironic approach found in this work.

While the criticism of Western forms of aggression in nineteenth-century China can easily be understood in terms of a revaluation of military strategies, a misunderstanding persists about Cai Guo-Qiang’s attitude toward contemporary Chinese politics. He justifies this attitude by detaching the subversive character of his work from the import of its antiestablishment stand. The movement for the celebration of cultural achievements is grafted onto the political sphere to such an extent that any confrontation between these two spheres would end up being unproductive. It is by recourse to this explanation that he justified his participation at the 2008 Peking Olympic Games as a special-effects designer.

Selected Bibliography

ANDREW, Julia F. and SHEN, Kuiyi. A Century in Crisis: Modernity and Tradition in the Art of Twentieth-Century China. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998.

CLARK, John. Modernity in Asian Art. University of Sydney East Asian Studies, 7. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993.

GALIKOWSKI, Maria. Art and Politics in China 1949-1984. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1998.

HOLMS, David. Art and Ideology in Revolutionary China. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

LU Xun. Lu Xun Quanji (Complete works of Lu Xun). 16 vols. Peking: Renminwenxue, 1995.

SULLIVAN, Michael. Art and Artists in Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

TANG, Xiaobing. Origins of the Avant-Garde: The Modern Woodcut Movement. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000.

YAN, Chen. L’Eveil de la Chine. Les bouleversements intellectuels après Mao, 1976-2002. La Tour d’Aigues: Éditions de l’Aube, 2002.

ZHANG, Xudon. Whither, China: Intellectual Politics in Contemporary China. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Estelle Bories received her doctorate at the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences-Po). She defended her dissertation in November 2011. Her dissertation research bore on contemporary art in China and the question of modernity. Bories’s principal publications have focused on the construction of artists’ identities, the evolution of Chinese critical literature, and changes in contemporary artistic production in Peking. She currently teaches at the University of Paris-3.

March 10, 2019

I discovered your site from Google as well as

I need to claim it was a wonderful locate. Thanks!

April 22, 2019

Great tremendous things here. I’m very glad to look your article. Thank you so much and i am taking a look ahead to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?

April 22, 2019

I’ve been surfing online more than 3 hours today, but I never discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It¡¦s pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made good content material as you did, the internet can be much more useful than ever before.

June 8, 2019

Every weekend i used to pay a visit this web site, for the reason that i wish for enjoyment,

since this this site conations truly good funny material too.

June 10, 2019

This is the perfect webpage for everyone who would like to find out about this topic.

You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you

(not that I actually would want to…HaHa). You certainly put a new spin on a subject which

has been written about for many years. Great stuff, just excellent!

June 12, 2019

My brother recommended I might like this web site.

He used to be totally right. This publish truly made my day.

You cann’t imagine just how so much time I had spent for this info!

Thanks!

June 13, 2019

Great delivery. Solid arguments. Keep up the amazing

effort.

June 13, 2019

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today, yet I never found any

interesting article like yours. It is pretty worth enough for me.

Personally, if all web owners and bloggers made good content as

you did, the internet will be much more useful than ever before.

June 13, 2019

Very nice write-up. I definitely love this site. Keep writing!

June 20, 2019

I simply could not depart your site prior to suggesting that I extremely loved the standard information an individual provide

for your guests? Is gonna be back frequently in order to check

up on new posts

October 3, 2019

Really informative article post.Really looking forward to read more. Great.

October 26, 2019

HyMx1D Major thankies for the article post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

November 7, 2019

Ztb1Xk Very good post. I am facing many of these issues as well..

November 12, 2019

I was suggested this web site through my cousin. I am now not certain whether or not

this publish is written by way of him as nobody else

realize such exact about my difficulty. You’re

incredible! Thank you!

November 21, 2019

There is definately a lot to know about this topic. I like all of

the points you made.

December 1, 2019

I was very happy to discover this site. I want to to thank you for ones time for this

particularly fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every little

bit of it and I have you saved as a favorite to see new things on your blog.

http://onlinecasinounion.us.com

January 1, 2020

I was just looking for this info for some time. After six hours of continuous Googleing, finally I got it in your site. I wonder what’s the lack of Google strategy that don’t rank this kind of informative sites in top of the list. Usually the top web sites are full of garbage.

January 21, 2020

Thank you for your blog.Much thanks again. Really Cool.