Following in the wake of the Dada movement, the saying “Art is life and life is art” was a leitmotiv in the 1950s and 1960s. Wolf Vostell falls within the scope of this outlook with his Theater Is in the Street (1958), where he championed the active participation of the audience, which had hitherto been confined to its role of passive spectator.

Julia Sissia—who is also preparing a thesis of post-1945 German art in France—inquires into the ways in which such audience participation could serve as a manifesto for the democratization of artistic practice and asks whether the goal of the documentation put together around this happening was to underscore its collective character in any other way than abstractly, or whether, instead, it was there just to forge and to stage the work itself. In that case, the author would remain master of these premises, at least for the time of this first episode.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Wolf Vostell's Theater Is in the Street:

Manifesto for an Artist Public?

Julie Sissia

Das Theater ist auf der Strasse: die Happenings von Wolf Vostell, exhibition catalogue (Leverkusen: Museum Morsbroich, 2010).

“Art is life, life is art.”[ref]For example, in the Wolf Vostell exhibition catalogue (1986; Museum of Modern Art of Strasbourg), designed by the artist, Vostell includes in his biography the following entry: “1961: He invents the formula ART = LIFE — LIFE = ART” (p. 69). Likewise, in the exhibition catalogue with the programmatic title Das Theater ist auf der Straße. Die Happenings von Wolf Vostell (Theater is in the street: the happenings of Wolf Vostell), which the museum of Leverkusen devoted to his work, presents as the epigraph for his biography, “Kunst ist Leben. Leben ist Kunst,” accompanied by the date 1961 (p. 331).[/ref] Such is the aesthetic principle of the work of Wolf Vostell (1932-1998). For the self-proclaimed inventor of the European happening,[ref]Wolf Vostell, exhibition catalogue (Hanover: Kestner Gesellschaft, 1977), p. 156.[/ref] Theater Is in the Street is not only a privileged example of the abolition of the boundary between art and life but also a historiographical milestone, a guarantee, in its author’s view, for his legitimacy within the history of art, understood as the history of avant-garde movements. In Theater Is in the Street, dated by the artist to 1958, the merger between art and life seems at first sight to be played out within a new connection between artist and public: for the isolated spectator, Theater Is in the Street is said to have substituted a gathering of persons, the public itself participating in the performance. To what extent does this work make of the public a creator of equal standing with the artist? Can public participation constitute a manifesto for democratization and for a collaborative practice of art? Is the goal of the documentation relating to Theater Is in the Street to underscore the collective character of this happening or is it to place the work itself within a historical setting and to stage it, to the point that this proves perhaps to be the sole mode of existence Theater Is in the Street would have ever had?

The Traces of the Performance

Vostell. Environnement, Happenings 1958-1974, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Musée d’Art moderne/ARC2, 1974).

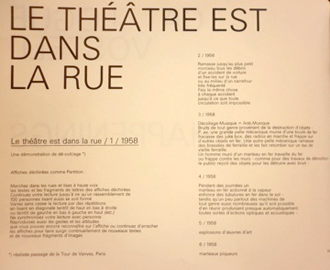

In the 1974 exhibition catalogue devoted to his work in Paris,[ref]Vostell, Environnements/Happenings 1958-1974, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC2, 1974), p. 84.[/ref] Vostell sets forth a series of actions that seem as if they should be carried out in a specific order. The public is to move through the streets of Paris and to read aloud there the fragments of characters they make out on torn billboard posters, until one hundred people gather. They are then to pick up pieces from a car accident and stick them together in the middle of the street until it becomes impossible for traffic to circulate. The text ends on the tone of a manifesto, affirming the mixed nature of décollage, which is also musical, and the public makes a final appearance in this “anticoncert” by destroying the scraps of metal. So, more than being a mere description of the unfolding of the performance, this text is itself of a hybrid nature that mixes improbable reality and action which are verging on fiction.

“Theater Is in the Street, 1958, documentation of the Happening/Rue de la Tour de Vanves, Paris, photograph on emulsified canvas, 108 cm x 100 cm, cat: no. 1,” caption and illustration from the Vostell. Retrospektive exhibition catalogue (Berlin: Neue Nationalgalerie, 1975), p. 85.

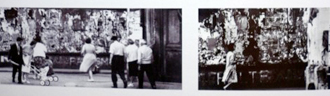

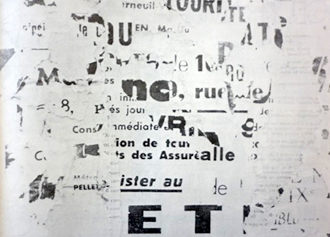

This performance is illustrated by a selection of photographs and reproductions of billboard-poster décollages. The 1974 exhibition catalogue reproduces the Et, das Theater ist auf der Straße billboard poster décollage,[ref]Ibid., p. 85.[/ref] which takes on the traditional rectangular format of painting. Yet, reproduced on the page facing the text, this décollage is captioned as “documentation of the Tour de Vanves street happening, 1958,” and is therefore detourned from its having an independent status as a work so as to adopt that of a trace of the performance. In another volume, published in 1969, four photographs are related to the action Theater Is in the Street.[ref]René Block, Wolf Vostell (Berlin, 1969), pp. 185-89.[/ref] The persons photographed do not notice the photographer, all of them having their backs turned or looking elsewhere. One observes no car, no construction site, none of the machines to which the text makes reference. Neither the artist nor any of the participants peeling [décollant] billboard posters is to be seen. Only the billboard posters in the background, in shreds, allow one to make some connection with the text: they comprise the decor of this “theater” scene in the street. The clash between these documents appears at first sight to be paradoxical as regards the public’s role in the work and as regards the very unfolding of the performance. Neither the photographs nor the Et, das Theater ist auf der Straße picture lay stress on the public’s participation as it was seemingly stipulated in the text.

Public Participation: Collective Reality . . .

In the article “Vostell’s Ruins: Dé-Collage and the Mnemotechnic Space of the Postwar City,”[ref]Claudia Mesch, “Vostell’s Ruins: Dé-collage and the Mnemotechnic Space of the Postwar City,” in Art History, 23:1 (March 2000): 88-115. [/ref] Claudia Mesch takes as a fact the active participation of spectators. For the American art historian, the performance is said to have been executed “in a particularly democratic gesture,” during which the participants “enact the role of the déaffichiste,” bringing “the habitually separate aspects of production and reception almost to the point of simultaneity.”[ref]Ibid., p. 93.[/ref] The narrative of the performance allows Mesch to define Theater Is in the Street as a “fully collaborative and performative” work.[ref]Ibid., p. 88.[/ref]

Such an interpretation of the role of the spectator in performance is recurrent in the history of this artistic practice since the late 1970s, when the first theories emerged. Thus, in 1979, in the article “notion(s) de performance,” Chantal Pontbriand defined performance as the “very articulation of life rather than illusion. It is a map, a form of writing that is deciphered in the moment, in the present, in the present situation, in a confrontation with the spectator.”[ref]Chantal Pontbriand, “Notion(s) de performance,” in Performance by Artists (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1979), quoted by Nathalie Boulouch and Elvan Zabunyan, “Introduction,” in Janig Bégoc, Nathalie Boulouch, and Elvan Zabunyan, La performance. Entre archives et pratiques contemporaines (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010), p. 13.[/ref] Likewise, Paul Ardenne bases his theory of a “contextual” form of art on the interaction between the public and the spectator, on “direct relationship, physical exchange, immediate reciprocity, with everything lived under the auspices of contact.”[ref]Paul Ardenne, Un art conceptuel. Création artistique en milieu urbain en situation d’intervention, de participation (Paris: Flammarion, 2002), p. 179.[/ref] The public’s co-creative, co-present participation in the performance, and all the more so in an urban context, seems to be a rule of this form of art. Several aspects of the text written by Vostell could go to corroborate this reading of the work. Does not the artist specify the actions the public is to carry out? Does he not merge the roles of the public and the artist in his employment of the imperative mood, for example when he writes “Walk in the streets and read aloud”? Is not everyone, whether he be a creative artist or not, therefore destined to act together and at the same time? Does not this action of Vostell thenceforth partake in a democratization of artistic practice, freed from the middle men of the art world, where artist and public are allied in a share rejection of the art market and in the “dynamiting of art objects”?[ref]He advocated the “dynamiting of art objects” (“Sprengungen von Kunstgegenständen”) in Vostell, Retrospektive 1958-1974, exhibition catalogue (Berlin: Nationalgalerie, 1975), p. 94. (German adaptation of the 1974 Parisian exhibition).[/ref] They are said to be working together, on an equal basis, toward abolishing the passivity of the spectator and, thereby, the latter’s subjection to consumer society—the society that billboard posters symbolize—so as to become, once again, agents . . . like the artist himself.

. . . Or Individual Fiction?

Text of the performance Theater Is in the Street, in Vostell. Environnements/Happenings 1958-1974, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Musée d’Art moderne/ARC2, 1974).

Now, many aspects of the work challenge an analysis formulated in terms of the work being “collaborative and performative.”[ref]“In a particularly democratic gesture, the participants of the dé-collage demonstration Tour de Vanves publicly enact the role of the déaffichiste. These demonstrations brought the habitually separate aspects of production and reception almost to the point of simultaneity. Dé-collage presented the public space of the street as a stage for both creation and radical critique which, while initiated by Vostell, could be completed by the public. The close relation of production and reception in dé-collage which is staged in Tour de Vanves positions active participation within the cognitive process of allegory to pose larger questions about the individual’s place within the present and her or his acknowledgment of the weight of the past within it” (Claudia Mesch, p. 93).[/ref] Indeed, the text is laid out in such a way as to blur the boundaries between description of a fictive scene and performed action, doing so in the very paragraphs where the public is supposedly acting. Moreover, performance time is also abstracted from the performance. Participation does not take place at a specific time; it is dated as 1958 in each paragraph, but its duration is not mentioned. These temporal specifications do not in fact give us any indication about the unfolding of the action within time. This time connection has a strained relationship with what Pontbriand observes: “The performance is based on a real and not fictive time. The literalness of the time and the space is a basic component. A performance often lasts for the time of the underlying process.”[ref]Chantal Pontbriand, “Notion(s) de performance,” in Performance by Artists, quoted by Nathalie Boulouch and Elvan Zabunyan, “Introduction,” in La Performance, p. 15.[/ref] The public, blended in with actions and poetic visions, gradually becomes an abstract feature of the text, too.

The same thing goes for the photographs, which in large part condition the ways in which we can form representations of happenings. As in many other performances, the photographs that have been chosen reappear in a recurrent way in publications about them.[ref]“Qua document, photography generally presupposes authenticity and commands authority,” notes Tracey Warr. “Long and complex performances involving public participation are reduced to a single image—the “good” image from the publisher’s standpoint—reproduced thousands of times in works.” This image that, by habit and for lack of alternative sources, comes to embody a whole production, eclipses the rest of the interpretation: it sheds light on a performance only by casting a shadow over what it does not capture. But this shadow cast upon the unfamiliar zones of the event is far from being simply ignored: quite to the contrary, obscurity encourages fantasy. The shadows are part of the picture one draws of a performance, like a “specter,” as Jean-Paul Martinon asserts. Paraphrasing Jacques Derrida, what Martinon means thereby is that which is allowed to be seen and that which merely allows itself to be imagined, supposed, and fantasized about” (Pierre Saurisse, “La performance des années 60 et ses mythes,” in Janig Bégoc, Nathalie Boulouch, and Elvan Zabunyan, La Performance, p. 35.[/ref] Yet, they represent no one who participated in the action; the people photographed are mere pedestrians engaged in their everyday activities, “anonymous passers by,” as the caption for the work recalls.[ref]See the captions for the illustrations relating to this performance in René Block, Wolf Vostell, p. 445 : “Das Theater ist auf der Straße, 1958, décollage in mehreren Pariser Straßen von Vostell und anonyme Passanten” (“Theater Is in the Street, 1958, décollage in the streets of Paris by Vostell and anonymous passers by”).[/ref] Indeed, on the photographs preserved in the Vostell archives, one makes out the names of the Rue Alfonse Karr and the Rue de Flandres, situated in Paris’s 19th arrondissement, far from the Passage de la Tour de Vanves by Montparnasse, where Vostell maintains his happening was carried out. Does Vostell want to insist on the contradiction between the text and the image, in the style of someone like Allan Kaprow, who deliberately underscored in this way the difference between a performed action and a memory trace thereof?[ref]Nathalie Boulouch and Elvan Zabunyan, “Introduction,” in Janig Bégoc, Nathalie Boulouch, and Elvan Zabunyan, La Performance, p. 27.[/ref]

A Larger-than-Life Montage

Vostell’s familiarity with the staging of texts and images, thanks to his training as a photolithographer and to his publishing activities,[ref]Wolf Vostell was the editor and creator of the review Décollage: Bulletin aktueller Ideen (and then Décollage: Bulletin der Fluxus und Happening Avantgarde) which appeared from 1962 (no. 1) to 1969 (no. 7).[/ref] invites us to consider the staging of performance in publications as an aspect of his oeuvre in its own right. So, might this work be an instance of photographic montage? And might it at the same time be reflecting the significance the artist wishes to grant to it retrospectively—more than ten years after its execution—within art history . . . that is, unless he has created it on the basis of independent works and documents so as to obtain an impression of continuity, coherence, and real participation?

An Abstract Public

The images and texts suggest that Theater Is in the Streets perhaps never existed as anything other than a published montage of photographs and texts. To our knowledge, this work is mentioned in no publication prior to 1969. So, is it not conceivable that Vostell, in the first publications he devoted exclusively to it, would have written the history of his work while going so far as to have completely invented some parts of it by playing on the supposed documentary objectivity of photography? Is not the sole really real spectator of this happening, in fact, the reader of the written works, handed over to a mental reconstruction of a work that exists only qua graphic montage? The reader then becomes a performing spectator and Vostell the theatrical director of his oeuvre and of this particular work in the history of avant-garde movements via the use of the very tools of art history: publications and exhibitions. Everything happens as if the public, understood as an abstract entity, fulfilled, more than the role of actor or co-creator, a purely rhetorical function. The challenging of the passivity of the spectator appears to be disembodied as much in the text as in the photographs. In this way, this anonymous public defined as a collective group acting within a fiction orchestrated by the artist does not violate the basically unique role of the artist but instead ranks him among those who make the history of avant-garde movements.

Bibliography

Das Theater ist auf der Strasse. Die Happenings von Wolf Vostell. Exhibition catalogue. Leverkusen: Museum Morsbroich, 2010.

ARDENNE, Paul. Un art conceptuel. Création artistique en milieu urbain en situation d’intervention, de participation. Paris: Flammarion, 2002.

BEGOC, Janig, BOULOUCH, Nathalie and Elvan ZABUNYAN. La performance. Entre archives et pratiques contemporaines. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010.

LANGSTON, Richard. Visions of Violence. German Avant-Gardes After Fascim, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008.

SIMON, Sidney. «Wolf Vostells Aktionsbildsprache.» In Vostell. Berlin: Editionen 17, 1969.

Vostell. Environnements/Happenings 1958-1974. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC2, 1974

Julie Sissia is writing her dissertation in art history at Sciences Po under Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and in Düsseldorf under Siegfried Gohr (joint thesis directors). She is a researcher working within the “A chacun son réel. La notion de réel dans les arts plastiques en France, RFA, RDA, Pologne des années 1960 à la fin des années 1980” (To each his reality; the notion of the real in the visual arts in France, FRG, GDR, and Poland from the 1960s to the late 1980s) project, which is financed by the ERC (European Research Council) Starting Grant Program, directed by Mathilde Arnoux, and hosted by the Centre allemand d’histoire de l’art (German art history center) in Paris.