Traditionally, people have often wanted to leave the last word to writers. Since Antiquity, with Philostratus, this has been because the critic was supposed to go beyond the world of appearances by sifting out a meaning and a moral, whereas the artist was suspected of doing nothing but representing forms through the use of other forms. Artists have regularly challenged this idea by imposing their own viewpoint and winning acceptance for the idea that mediators prevent people from seeing works and from appreciating them as they ought to be. Indeed, they have regularly created a crisis for the established hierarchies. In particular, during the early twentieth century, avant-garde movements have shaken up not only the established forms but also the way in which forms are learned, presented, sold, and commented upon. Thus, as Olga Medvedkova tells us, as early as 1901 Wassily Kandinsky violently attacked critics, and more generally all mediators, whom he accused of being parasitic. As for Elitza Dulguerova, what she reveals to us is the powerful case of Vladimir Tatlin and his 1916 Futurist exhibition in Moscow, The Store, which called back into question the rules governing the arts scene as regards the art economy.

These two quite original research papers reveal to us a major facet of the critical role played by artists themselves, who are no strangers to the politics of art and are, rather, active agents in its implementation.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of May 14th 2009

The Store: Negotiating Exhibition Value at the Time of the Russian Avant-Garde*

Elitza Dulguerova

Exhibition Malaise

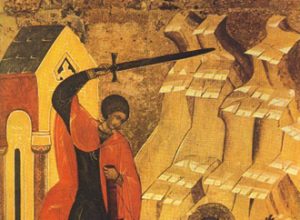

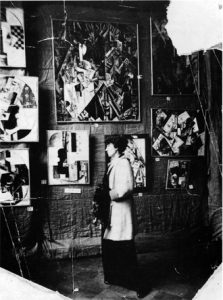

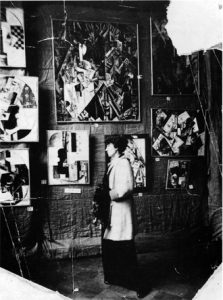

Fig. 1 Alexandra Exter in front of Nadezhda Udaltsova’s paintings at The Store exhibition. Moscow, 1916.

“The remnant of artistic sensibility that lingers in our age bids fair to be systematically crushed out by these exhibitions…This is the end of the history of pictures… Once the symbol of the holiest, diffusing reverence in the church, and standing above mankind like the Divinity itself, the picture has become the diversion of an idle moment; the church is now a booth in a fair; the worshippers of old are frivolous characters”[ref]Julius Meier-Graefe, “The Mediums of Art, Past and Present,” in Modern Art: Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics [1904]. Trans. F. Simmonds and G. Chrystal (London and New York: William Heinemann and G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908), vol. 1, p. 11.[/ref]

Beyond the major art exhibitions issuing from the tradition of the Salons, this statement by the art historian Julius Meier-Graefe was meant to encompass the general phenomenon of the temporary exhibition as the emblematic arts institution of capitalist modernity which, in transforming the ways in which works circulate, are distributed, and are received, had affected how artistic practices were defined and indeed shook up the very notion of the work of art. A visible indication of the diversification of artistic practices and of their respective audiences, as well as of the growing propinquity between artworks and commercial commodities, exhibitions became a special target for criticism at the turn of the twentieth century. It would not be an exaggeration to say that, in the view of several art critics and artists, this modern socioeconomic constraint exemplified at the time the crisis of the symbolic authority of art.

In Russia, these preoccupations made themselves felt all the more strongly as temporary group shows remained, in the absence of larger structures of the “Salon” type as well as of the established dealer-critic system, the dominant form for the presentation of art. The exhibitions of Russian avant-garde artists in the 1910s fitted therefore into a preexisting format, though they shook up conventions by exploiting the implicit eventfulness of that format and by adopting various practices for intervening in the public space (manifestos, provocative debates, an effort to expand exhibitions toward the space of the mass media).

Fig. 2 Pavel Kuznetsov, Birth, 1906, pastels on canvas, 73 x 66 cm, Moscow, Tretyakov National Gallery.

The exhibition entitled The Store, which was organized by Vladimir Tatlin from March 19 to April 20, 1916, presented ninety-five post-Cubist works by thirteen artists on the premises of a vacant storefront in central Moscow (Figure 1)[ref]Lev Bruni, Alexandra Exter, Valentin Yustitsky, Ivan Kliun, Kazimir Malevich, Alexei Morgunov, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Vera Pestel, Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Sophia Tolstaya, Marie Vassilieff. For a reproduction of the catalogue, see Larissa Zhadova, ed., Tatlin [1984]. London: Thames and Hudson, 1988.[/ref]. While continuing the tradition of Futurist exhibitions, this particular one stood out on account of the little discursive effort addressed to the public and the press. The Store nonetheless afforded a particularly audacious attempt to rethink, starting from the site where art is offered to one’s view, the conventions governing its perception and its appreciation, the distinctions between artworks, everyday objects, and commodities in the capitalist art economy, as well as the role of exhibitions. While beliefs in the magical economy of contact with the work of art still dominated the expectations of most artists and art critics toward art, The Store demonstrated–through its choice of title and of site and through the selection of works–that socioeconomic conditions had to be taken into consideration in dialogue with, and not in opposition to, artistic practices. In order to understand this provocative move, we must first situate existing usages of exhibitions, which entailed a recognition that temporary exhibitions were a new kind of arts institution, but tended however to minimize, nay to contain, the commercial side of exhibitions either by emphasizing the spiritual side of art or by drawing a clear distinction between artistic value and commercial value.

The Promise of the “Chapel-Exhibition”

In the quest for a viable alternative to the alleged misdeeds of commercial exhibitions, the critics had forged in their discourses the paradoxical figure of the “chapel-exhibition.” Consider, for example, the following review of the 1907 Symbolist exhibition called The Blue Rose:

“For a long time, art was called a temple. Now we speak of chapels for art. Each new group of artists–a new chapel, for a few. Is this not because the temple has been transformed into a street bazaar?

The Blue Rose is a beautiful chapel exhibition. For a very few. And it is all the further removed from the sacrilege of the ‘merchants in the temple.’

Clarity. Silence. And pictures–like prayers. Timid and maladroit, too solitary or insufficiently pious, yet still prayers.”[ref]Sergei Makovsky, “Golubaya Roza” [The Blue Rose], Zolotoe runo, 5 (1907): 25.[/ref]

Fig. 3 Nadezhda Udaltsova, Restaurant, 1915, oil on canvas, 134 x 116 cm, Saint Petersburg, Russian Museum.

These brief lines were formulating a major concern of Russian art criticism: How, when the number of artists’ societies and groups of artists was constantly growing and when the channels of production and distribution were expanding and audiences were scattering, was one to rediscover a unified concept of art that would give rise to unifying experiences for the public? The “chapel-exhibition” was able to convert the existing socioeconomic constraints, thanks to the formal and thematic coherence afforded by a limited set of works (in The Blue Rose exhibition, the irresolute impressionist technique evoked the elusive immateriality of the mysteries being represented; see Figure 2). But above all, this sort of exhibition could allow for a convergence of artistic and religious experience and create the conditions for a communion among those visiting the exhibition. The “chapel-exhibition” thus mitigated another modern danger that accompanied the desacralization of art and its transformation into a commodity: individualism, which the critic Alexandre Benois had described in 1906 as an “artistic heresy” precisely because it failed to create for the public the conditions for a shared experience of art.

On the Distinction Between an Art Store and an Exhibition

A more secular way of containing the effects of the constraints exhibitions impose upon artworks was to specify the characteristics of public exhibitions and to delineate the latter through their usage from the more commercial contexts for the presentation of art. The critical journal Apollo could thus reproach Nadezhda Dobychina’s Artistic Bureau, the first private modern gallery in Saint Petersburg, for coming close to being an exhibition and for not respecting its professional territory: “Why does her store (even though it is nicely and carefully organized) publish a catalogue for sale and collect entrance fees, attempting to look not like what it is in reality, a store, but like an exhibition?”[ref]Anon. “Postoyannaya vystavka khudozhestvennogo byuro N. E. Dobychinoi ” [The permanent exhibition of the Artistic Bureau of de N. E. Dobychina], Apollo, 8 (1913): 62.[/ref] While exhibitions, like art stores, were channels for the distribution of art, the values they allocated to artworks were appraised differently. The entrance fee ensured a public role for exhibitions, and works could become “not liable to public exhibition” (to borrow the expression of a critic on the topic of Futurist exhibitions) if they infringed upon the accumulation of symbolic capital.[ref]L. S-ii,“Iz tekushchei zhizni” [On everyday life], Petrogradskie vedomosti, 288 (December 30, 1915). On the relationship between time and artworks, see Eric Michaud, “Capitalisation du temps et réalité du charisme,” in Pierre Encrevé et Rose-Marie Lagrave (eds.), Travailler avec Bourdieu (Paris: Flammarion, 2003), pp. 281-88.[/ref] Artistic value was therefore based on the capitalization of time spent in front of the work in a public context, which justified the fee-based nature of exhibitions; as for the commercial value, it concerned only the good to be acquired in the private context of art “stores.” Even in the absence of overtly religious references, the value of art remained based on a magical economy of contact with the work, which public exhibitions ought to guarantee.

An “Austere Shopwindow for Things”

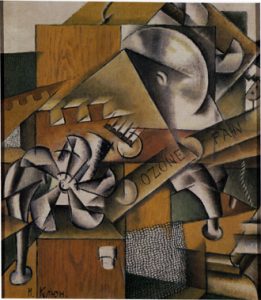

Fig. 4 Ivan Kliun, Ozonator, 1914, oil on canvas, 75×66 cm, Saint Petersburg, Russian Museum.

The exhibition Tatlin organized in 1916 destabilized belief in the “chapel-exhibition.” It also disturbed the established distinctions between artistic value and commercial value.

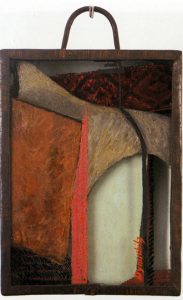

In addition to the tautological reference to the site at which it was held (a choice that also was revelatory of the penury of places for exhibitions in Moscow), the title The Store was redundant with respect to the everyday themes and materials of the works exhibited. The Post-Cubist drawings, paintings, and assemblages represented the quotidian modernity of urban sites (Figure 3) and of technological innovations (Figure 4); they made it present, too, through the artists’ recourse to such mundane materials as glass, untreated wood, and metal (Figures 5 and 6).

Such works were at the time either ignored by critics as not belonging to the domain of art (Alexandre Benois) or seen as the epitome of the crisis of modern Russian art. For Yakov Tugendkhold, for example, Tatlin’s counter-reliefs no longer pertained to experimentation with art as device but marked, rather, the ultimate retreat into an individualistic monologue that was no longer artistic in character since it offered no common basis for a shared experience. In his 1915 article, “In the Iron Dead-End,” he had reproached Tatlin for breaking down the difference between representation and presence and for replacing the Cubist quest for the representation of contrasting forms, volumes, and textures (faktura) with the presence of the forms, volumes, and textures of the materials being used (iron, glass, aluminum, and tar; see Figure 6). Their exclusively material value relegated them in Tugendkhold’s opinion to “the austere black-gray-and-white shopwindow of Tatlin’s things.”[ref]Yakov Tugendkhold, “V zheleznom tupike (po povodu odnoi moskovskoi vystavki)” [In the iron dead-end (On a Moscow exhibition)], Severnye zapiski, 7-8 (July-August 1915): 105, emphasis added.[/ref]

Tatlin’s Strategy

Fig. 5 Sofia Dymshits-Tolstaya, Glass Relief, ca. 1920, mixed media on glass with steel frame, 24 x 17.5 x 5 cm, New York, Rosa Esman Gallery.

Tatlin’s choice, at the time of The Store, to bring together Futurist and Cubist canvases and assemblages on commercial premises with a tautological title was a manifestation of his willingness to think art and the market together without, for all that, “reducing” works to commodities. This placed him in a position where he stood apart from the majority of his contemporaries, including Mikhail Larionov, that Russian Marinetti for whom the market was but an evil necessary for the survival of art.

This claim of continuity cohered very strongly with the artistic practice of Tatlin, whose respect for materials led him to use them as such, without altering them or sublimating them into a representation. The form of each assemblage was determined by the specificities of each material and its encounter with the other materials.[ref] See Maria Gough, “Faktura: The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde,” RES, 36 (Autumn 1999): 32-59.[/ref]

This concern to work with the parameters and the characteristics of the environment was one of the major points of disagreement between Tatlin and Malevich, whose Suprematist project was aimed, on the contrary, at expressing the experience of the world in a codified pictorial language. And while Malevich was invited to participate in The Store, it was on the condition that he not show there his Suprematist paintings. The Store’s materialist stance, which expanded Tatlin’s preoccupations to the scale of an entire exhibition, can thus be read as a riposte to The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0, 10 (Zero-Ten) held three months earlier in Petrograd.

Now, while Tatlin was undoing the customs connected with exhibitions and stores, he was not unknotting their relationship but was opting, instead, for a strategy of indetermination. Although less known than Malevich’s visual manifesto of Suprematism at 0, 10, this approach was at once audacious and fragile, and it disturbed the usual criteria for evaluating works as much as it upset the existing beliefs in what spaces for art and their role should be.

Indeed, an exhibition entitled The Store, being held on the premises of a store and showing things that were not art, infringed upon the religious economy of the “chapel-exhibition.” It was not an “art store,” since the institutional conditions he assembled were those of a public exhibition. A critic suggested that this was an exhibition whose premises were “laid out like” a store, thereby misreading, through this representational figure, the import of Tatlin’s gesture: doing an exhibition in a store, not staging it.

A Materialist Utopia of Continuity

Fig. 6 Vladimir Tatlin, Pictorial Relief 1915, 1915, wood, plaster, tar, glass, metal leaves, 110 x 85 cm [extrapolated materials; work has disappeared].

The Store connects to Tatlin’s counter-reliefs and other assemblages in what Viktor Shklovsky was to call, in 1920, the utopia of a “continuous world,” in other words, of a view of art as a way of actualizing everyday life (byt), rather than as a way of rejecting it. For Shklovsky, Tatlin’s project both had the ambition and gave itself the means to produce “a new palpable world” that was not opposed to the external world. Yet in this homage to continuity, the theorist quite lucidly discerned a side that was utopian and unrealizable:

“I do not know whether Tatlin is right or wrong. I do not know whether the bent tin sheets in his students’ compositions can grow into the hammered counter-reliefs of the new world. I do not believe in miracles, but that is why I am not an artist.”[ref]Viktor Shklovsky, “O fakture i kontrrel’efakh”, Zhizn’ iskusstva, October 20, 1920; English translation “On Faktura and Counter-Reliefs,” in Larissa Zhadova, ed., Tatlin [1984] (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), p. 342. [/ref]. »

Tatlin’s attempt to organize a group show belongs, even if before the revolution, to the same utopian impulse. (This would perhaps explain why it was a practical failure, in terms of media coverage, visits, and sales.) Yet above all, The Store shows that modern artists like Tatlin were aware that exhibitions were a condition for seeing, perceiving, understanding, and remembering art in the process of its being made and that the experience in which works were perceived depended upon the conditions of display, circulation, and commercial distribution of art.

Bibliography

Bätschmann, Oskar. The Artist in the Modern World: The Conflict Between Market and Self-Expression. Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 1997.

Benois, Alexandre.“Khudozhestvennye eresi/Les hérésies artistiques.” In Zolotoe Runo/La Toison d’or, 2 (1906): 80-88 (bilingual publication).

Dulguerova, Elitza. L’exposition d’avant-garde comme utopie de l’espace public. Doctoral thesis. Paris/Montréal: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Socales/Université de Montréal, 2006.

Gough, Maria. “Faktura. The Making of the Russian Avant-Garde.” RES, 36 (Autumn 1999): 32-59.

Makovsky, Sergei. “Golubaya Roza” [The Blue Rose]. Zolotoe Runo, 5 (1907): 25-28.

Michaud, Eric. “Capitalisation du temps et réalité du charisme.” In Pierre Encrevé et Rose-Marie Lagrave. Eds. Travailler avec Bourdieu. Paris: Flammarion, 2003. Pp. 281-88.

Shklovsky, Viktor. “On Faktura and Counter-Reliefs.” In Larissa Zhadova. Ed. Tatlin [1984]. London: Thames and Hudson, 1988. Pp. 340-342.

Tugendkhold, Yakov. “V zheleznom tupike (po povodu odnoi moskovskoi vystavki).” [In the iron dead-end (On a Moscow exhibition)]. Severnye zapiski, 7-8 (July-August 1915): 102-11.

Zhadova, Larissa. Ed. Tatlin [1984]. London: Thames and Hudson, 1988.

Elitza Dulguerova is Assistant Professor at the Université de Paris I – Panthéon-Sorbonne. She holds a joint doctorate in Art History from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and the Université de Montréal. In 2008-2009 she was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University. Her thesis, Usages et utopies: l’exposition dans l’avant-garde russe prérévolutionnaire (1900-1916), will soon appear from the Presses du réel. She works on the social history of art and the history of ideas in the age of the historical avant-garde movements as well as on the theory of exhibitions as an artistic and social issue in twentieth-century art. Her recent publications include: “De l’hétéronomie de l’art moderne,” in Marion Froger and Jürgen E. Müller (eds.), Intermédialité et socialité. Histoire et géographie d’un concept (Münster: Nodus Publikationen, 2007), pp. 39-50; “L’exposition: un espace public contingent chez les avant-gardes historiques (1910-20),” in Élisabeth Caillet and Catherine Perret (eds.), L’art contemporain et son exposition (2) (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007), pp. 71-85; “L’art autonome in situ. Pensée de l’exposition chez Mikhaïl Larionov (Moscou, 1913),” Kritische Berichte, 33:3 (2005): 28-39.

* Other versions of this text have been presented at the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (CREEES) and at the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University. I wish to thank Robert Wessling and especially Maria Gough, as well as the public for their comments.