The Surrealists reinvented the idol of origins. They dreamed of their Primitive as someone standing apart from science and reality by curiously rediscovering the paths of history. As early as the 1920s, they were among the first to revolt against the serfage of non-Western peoples, and they did so not by calling, in the name of fine sentiments, for some moderation in the ways these peoples were being subjugated but by calling for a radical condemnation of the very conditions of colonialism.

The history of art retains especially André Breton’s passion for Eskimo, Indian, and South Sea masks and for the dolls of the Hopi Indians of Arizona, of which he kept some beautiful specimens. He did so because he admired their expressive and poetic value, the very same value he sought everywhere else as so many signs of life in a modern world whose disenchantment he tirelessly denounced.

For, the basic problem was less the other than one’s own self, caught in the nets of a Western world whose alienation and decay were being heralded by its poets. Antimodern, yet at the very heart of modernity, the Surrealists opened the way toward the kinds of reflections art history is taking note of today.

Aby Warburg, Jean Laude, and a few others have spoken of the indispensable contributions of anthropology and ethnology and of how unstable were the status of the artist and of the art work and, necessarily along with them, the criteria of uniqueness, originality, and superiority. At a time when the new Quai Branly Museum is looking like Pandora’s Box while inviting comparison with other countries and other ways of presenting collections, the remarkable studies by Nélia Dias, Sophie Leclercq, and Maureen Murphy reopen the file on a shaky identity.

More broadly speaking, we can say that it is discontent with civilization itself that was at issue here. Michel Leiris had noted the coexistence of such discontent with a culture in which everything seemed to have been said already because a certain level of technological development had been achieved but in which that development had been rendered possible only by stifling certain aspirations for the infinite.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of November 23, 2006

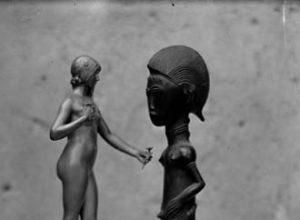

Nélia DiasThe Western Fascination with Non-Western Objects

The talks given by Sophie Leclercq and Maureen Murphy bear on the reception of non-Western objects in France during the interwar period. The first talk fastens on the process of the Surrealists’ appropriation of non-Western arts; the second bears on the way in which non-Western arts acquired different statuses in terms of the changing setting–that of ethnographic museums, private galleries, or the artistic avant-garde. Both texts retrace a portion of the history of the variations in status of non-Western objects in France by placing the accent on the tensions these objects surround: there were tensions between, on the one hand, the aesthetic approach and the ethnographic approach and, on the other, between an interest in non-Western arts and the return to classical values. But might things have been otherwise? As Ernst Gombrich has pertinently noted, “‘preference for the primitive’ may be often tantamount to a rejection.”[ref]Ernst Hans Gombrich, The Preference for the Primitive: Episodes in the History of Western Taste and Art (London and New York: Phaidon, 2002), p.7.[/ref] Thus, it is just as interesting to examine the infatuation with non-Western arts as the rejection associated with it.

Fascination with Non-Western Objects or with Collectors?

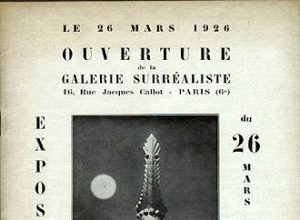

Leclercq examines the “fascination with the Other” that underlies the Surrealist appropriation of non-Western arts and rightly poses the question whether the Surrealists’ infatuation with non-Western arts stems from a kind of “anticonformism or, on the contrary, a certain sort of herd instinct, an adaptation to the trend of their milieu.” She notes that the Surrealists’ interest bore on Amerindian art, and in particular on the art of North America, stating that “this criterion of novelty played a role in the predilection Surrealists had for Indian America.” Moreover, it is no accident that a Kachina doll figured on the presentation notice for the 1936 Surrealist Exhibition of Objects. One may ask oneself why the Surrealists chose Amerindian art.

Leclercq cites a number of exhibitions–“Yves Tanguy and Objects from America” (1927), “The Surrealist Exhibition of Objects” (1936)–collections–notably those of Breton and of Éluard–and texts–in particular those of Breton–that testify to this infatuation. It is fitting to note that, during those same years, a number of events devoted to Amerindian arts took place in Paris, as was the case with the “Exhibition of the Art of America” at the Marsan Pavilion in Paris in 1928, whose catalogue contains texts by Paul Rivet, Alfred Métraux, and Georges Bataille.

How is one to make sense of this infatuation? In an article that appeared recently in Le Monde[ref]Roxana Azimi, “L’Art esquimau pulvérise régulièrement les estimations des spécialistes,” Le Monde, November 19-20, 2006: 23.[/ref] on the topic of the sale of Yup’ik masks from the Robert Lebel collection, one of the people interviewed, Pierre Amrouche, stated the following: “Rightly or wrongly, the Surrealists thought that Eskimo art was the very expression of the unconscious, on account of the ambivalence in zoo-anthropomorphic representations. They thought that these objects drove the spectator to dreaming, to an inward voyage, instead of transmitting some sort of direct message. They had a romantic vision of this world, which was perceived as one of the last territories of freedom.”[ref]Quoted by Benoît de L’Estoile, “Le musée des ‘arts premiers’ face à l’histoire,” Arquivos do Centro Cultural Calouste Gulbenkian, 45 (2003): 49.[/ref]

While the symbolic dimension played a nonnegligible role in the Surrealists’ fascination with Amerindian objects, can one, for all that, maintain that the Surrealist approach fits into a specific history, that of collector-artists from the “first generation of Primitivism”? And, while, as Leclercq mentioned during her November 2006 talk in the present seminar, “the high level of emotion the dispersal of the Breton collection provoked in 2003 is part of the fascination that collection has exerted over the years,” does this fascination, in our time, bear on the objects themselves or on the people who collected those objects? It is surely the latter aspect that influences auction prices; during the Breton sale in 2003, an “Eskimo” mask painted in red ochre representing the sun had attained 198,704 euros.

Ethnology, Surrealism, Colonialism

Leclercq analyses the Surrealist Exhibition of Objects and mentions the distinction between a Surrealist exhibition of objects and an exhibition of Surrealist objects. It would be worth examining this distinction in greater depth, for it would allow one to offer a better response to the following questions: What is a Surrealist object? How can a non-Western object become a Surrealist object? And, conversely, how does a non-Western object become an ethnological object? In short, are there some points of convergence between the process of constructing an ethnographical object and that of constructing a Surrealist object?

The relations between the political dimension and the appropriation of non-Western objects are brought out by Leclercq, who underscores the ambiguity on the part of the Surrealists, in particular Paul Éluard and André Breton, with regard to colonial policy. Even as they criticized the Colonial Exhibition, they nonetheless were aware of the advantage they could draw from the sale of their collections at the very time this Colonial Exhibition was taking place. Murphy shows how the Musée de l’Homme and the Museum of the Colonies worked “for a better knowledge and a greater visibility of objects brought back from the colonies.” A certain number of collectors were participating around the same time in the “Exhibition of the Indigenous Art of the French Colonies” at the French Museum of Decorative Arts (1923). Indeed, this exhibition seems to have been such a success that the collectors André Level and Henri Clouzot noted that “the public was ripe for appreciating the new art material it was being offered.” They mention, however, the difficulty both visitors and critics had in appreciating African fetishes, “works that are more taxing, but sometimes more elevated and still more significant.” A few years later, a number of collectors, including some who were also dealers (such as André Lefèvre, Charles Ratton, and Louis Carré), played a key role in the selection of the objects presented in the “Exhibition of Indigenous Arts” at the Colonial Exhibition of 1931, to which they lent works. According to Benoît de l’Estoile, “for these enlightened collectors of the interwar period, exhibition of Negro art and a colonial exhibition belonged in the same category and were frequented by comparable publics.”[ref]Benoît de L’Estoile, pp. 50-51. See also Jody Blake, “The Truth about the Colonies, 1931: Art Indigène in the Service of the Revolution,” Oxford Art Journal, 25:1 (2002): 35-58.[/ref]

It was also in this same year of 1931 that Marcel Mauss published an article entitled “The Indigenous Arts.” In this article, the French ethnologist mentioned “the entry of this art, which differs from our classical arts, into our own way of thinking . . . a beautiful mask from the dark country or a Javanese puppet no longer seems ridiculous to us; a bronze from Benin or poured and patinated jewelry from Dahomey impresses the new generation and expresses something for it.” Mauss could not help but recognize the fascination non-Western arts were exerting upon the younger generations, and he underscored the way in which youth had been won over to all those arts: youth “danses to the sound of jazz after having long been limited to the tango,” the famous ethnologist added. Yet Mauss did not remain merely on the level of fascination; the recognition of the aesthetic dimension of non-Western products constituted one of the pathways to, on the one hand, recognition of the equal worth of all forms of artistic production and, on the other hand, to a relativistic approach to cultures. “One is beginning to understand that the art of our civilizations is but one instance of art in general. The indigenous arts are arts that are relatively as ‘worthy’ as many of ours. Contact with them refreshes our arts: it suggests new forms, new styles, even when they have become, through tradition, as stylized and as sophisticated as our own.”[ref]Marcel Mauss, “Les Arts Indigènes,” Lyon Universitaire, 14 (April/May 1931): 1-2.[/ref] The emphasis Mauss placed as early as 1931 on the equal worth of all forms of artistic production is part of a broader theoretical concern about respect for cultural diversity as well as cultural relativism.

Discovery of “Primitive Art” and Rediscovery of the Surrealist Legacy

Both of these talks raise a pair of more general questions. The first question may be expressed as follows: To what extent can it be advanced that it was during the interwar period that the perception of “primitive” art changed? And if change there may have been, was it due to the institutionalization of ethnology in France and to the role played there by the French Musée de l’Homme (Museum of Man)? In other words, did the world of art and ethnology share one and the same concern with non-Western arts and did they thereby have in common one and the same definition of art?

The second question relates back to what could be called the link between the “fascination” with non-Western arts and geographical sites. In following the history of the reception of non-Western arts in France, one cannot help but notice the existence of successive waves: first, there was the “discovery” of the arts of Africa and Oceania in the early twentieth century and then the “discovery” of the arts of the Americas during the interwar period. Can one detect a kinship between these two “discoveries” by Western artists? It is not uninteresting to note that the Quai Branly Museum, and in particular its D’un regard l’Autre (“Regarding the Other”) exhibition, explicitly highlighted the Surrealist legacy. One can then ask oneself why this museum is so “fascinated” by the Surrealists as collectors who, in turn, were “fascinated” by non-Western objects.

Professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Lisbon, Néla Dias is the author of Le Muséé d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, 1878-1908. Anthropologie et Muséologie en France (Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1991) and La Mesure des Sens. Les anthropologues et le corps humain au XIXe siècle (Paris: Aubier, 2004) as well as numerous articles on the history of anthropology in France and on ethnographic collections. Her recent publications bear on, among other topics, the Quai Branly Museum: “Esquisse ethnographique d’un projet: le Musée du quai Branly,” French Politics, Culture & Society, 19:2 (2001): 81-101;

“Une place au Louvre,” in Le Musée cannibale, ed. Marc-Olivier Gonseth, Jacques Hainard, and Roland Kaehr (Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnographie, 2002); “Ethnographie, arts, arts premiers: la question des désignations,” Arquivos do Centro Cultural Calouste Gulbenkian, 45 (2003): 3-13; and “Qu’est-ce que les ‘arts premiers’?”, Sciences Humaines, June-July-August 2006: 8-11.