In the middle of the nineteenth century, the reaction against spiritualism was a prelude to the struggle that would start up against art for art’s sake–against art seen as autonomous and rid of all social responsibility. A certain number of thinkers paved the way at the time by attacking this vision of an ethereal, deceptive, and stupidly comforting world, and they showed that the Heaven of Platon or Bossuet was but a sorry refuge when what was needed was to face reality. In his Philosophes classiques du XIXe siècle (Classical philosophers of the nineteenth century, 1857), Hippolyte Taine called upon people to take up again the realist tradition and to place themselves on the ground of facts and science.

It is well known to what extent this return to the real was ill greeted by the critics, who denounced its hideous materialism and its obsession with evil. With no Hereafter, this sort of realism could be the harshest kind possible and the most resolutely opposed to any kind of moralizing aesthetic. Behind its expressions of detestation loomed a critique of Germany that, starting in 1870, was to combat, inch by inch, the spell of a nation Madame de Staël had cast in De l’Allemagne (Germany, 1814). The liberal union of neighbors (a prefiguration of Europe) so wished for by the Renans and Taines was then jettisoned in favor of a return to a France injured in its pride and ready for revenge.

While one side of the French intellect shut itself off amid its feelings of disenchantment, the other side devoted all its forces to a reconstructive effort. It was in the wake of this energetic rebirth that the idea prospered of creating a kind of art that would be so connected with social life and morality that it could change the old world. Indeed, between 1889 and 1914 debates were rife around the topic of “social art.” As Catherine Méneux shows, social art could not completely deny the autonomy and freedom of action gained from modern artists. In an industrial society that was undergoing a complete reshaping of its economic, political, and religious framework, art was one of the symbolic objects numerous actors took up in order to invent a more just society–one in which each person would have access to culture, to beauty, and to harmony in the private realm as well as in the public space. We rediscover, in this way, the premises of Saint-Simonism, the philosophy of Taine, and the rationalism of Viollet-le-Duc, to which were added anarchist impulses and, from abroad, the efficacy of the English (with William Morris, especially) and Belgian models.

Christophe Prochasson insists upon the exceptional character of this turn-of-the-century history, a “moment” in which it seemed possible to bring art, politics, and science into harmony. He is very well aware of the contradictions that were inherent in these hopes of seeing art reconciled with the people when the latter were viewed as alarming on account of their mass character and their supposed absence of “good” taste. Added thereto were social art’s numerical weakness and the paucity of its real achievements, followed by the funeral toll of the Great War.

Defense of a kind of art that would be both modern and French was, of course, blocked by the outbreak of world conflict. Yet it was to reemerge in the 1920s and 1930s in new ways and with a clearer, State-led willingness to act whose effects could be felt above all at the 1937 International Exhibition of Arts and Technologies. After the combats in favor of “social art” came the intestine struggles of anarchists who had defended modernity against the eternal poverty advocated by their theorist Peter Kropotkin, and there were fights with Picasso, too, who had so established himself as the artist capable of linking together modern individual freedom and history that Robert Delaunay could cheekily declare in 1935: “Me, artist, me manual worker, I’m making revolution right on the premises.”

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of September 21, 2006

Catherine MéneuxSocial Art at the Turn of the Century

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, there were two opposing views of art: the idea of art as “finality without end”–as an autonomous activity whose criteria are defined by artists themselves–and the one that saw in art a means of expression subordinated to the ends of social life, to the common interest, and to morality[ref]On the first half of the nineteenth century, see: Neil McWilliam, Dreams of Happiness: Social Art and the French Left, 1830-1850 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Press University, 1993).[/ref]. Described early on as “social art,” this second way of conceiving of art became the object of particularly important debates between 1889 and 1914. As soon as the democratic State began to intervene in artistic life, the question of the relations between art and society became of concern to the entire citizenry. In light of the State’s cultural policy, some critics raised the problem of the social utility of art and of the effect art works have on the spectator. As for the artists themselves, in texts, in actions, and in artistic works they expressed themselves about their potential social role. Writers also fed these discussions. The debates over social art were thus articulated around four distinct poles, which were literary, artistic, critical, and political. Generally, these debates bore on the question of the social function of art in an industrial and commercial society, whereas what artists endeavored to gain was some genuine autonomy and to be judged on a single criterion, their originality, and therefore on the expressive force of their individuality[ref]Alain Bonnet, L’enseignement des arts au XIXe siècle. La réforme de l’École des Beaux-arts de 1863 et la fin du modèle académique (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2006); Eric Michaud, “Autonomie et distraction,” in Histoire de l’art. Une discipline à ses frontières (Paris: Editions Hazan, 2005), pp. 13-47.[/ref].

The Renewal of Social Art in the Time of Symbolism and Anarchism

Fig. 1: Jules Desbois, Cider jug, 1890-1893, poured pewter, 21 x 15 x 12.5 cm. Paris, Orsay Museum.

Social art became a major object of discussion among literary and artistic elites as republican society and liberal paternalism began more and more to be challenged. The creation, by writers, of the Club for Social Art (1889-1890), then of the review L’Art social (1891-1894), testifies to this[ref]Françoise Scoffham-Peufly, Les problèmes de l’art social à travers les revues politico-littéraires en Allemagne 1890-1896, master’s thesis supervised by Madeleine Rébérioux and Jean Levaillant at Paris VIII-Vincennes in 1970.[/ref]. Attacking bourgeois individualism and symbolist literature, these writers advocated a revolution through art and popular access to culture. In 1892, Paul Desjardins, Gabriel Séailles, and a few others created an association called The Union for Moral Action. Spiritualists, they wished to work through charity for the people. They thus encouraged the reproduction of masterpieces as well as the dissemination of popular culture and the promotion of artists deemed by them to be ideal, such Puvis de Chavannes[ref]Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond, “L’Enfance de Sainte-Geneviève: une affiche de Puvis de Chavannes au service de l’Union pour l’action morale,” Revue de l’art, 109 (3, 1995): 63-74.[/ref]. Critics like Roger Marx also set out to promote decorative art, invoking both utility and modernity. As for the artists in the Symbolist movement, they put their energies into popular crafts. (Fig. 1) While not democratic, this craft industry was at least popular because it borrowed from popularly developed forms. A work thus became the site where the artist and the proletarian were united.

Nevertheless, all these ideas constituted but a false start, inasmuch as the true questions were not really being raised. Indeed, the demands being put forth bore more on the freedom of the creative artist than on his eventual integration into industrial society. The years 1894-1895 thus were the occasion for a first retrospective assessment. Symbolist decorative art was criticized, for it emanated from artists working individually, far from national traditions, to the detriment of a single, collective style. The objects being created were also too refined to be accessible to the people. Debates began to form around the “art industries” and architecture. Moreover, a number of commentators looked abroad. William Morris became the object of ardent admiration. Indeed, not only had he originated a modern, national, and popular art, but he offered a genuine doctrine for combining art and democracy, without for all that “compromising” with dealers and industrialists[ref]See also Relire Ruskin, a lecture series at the Louvre Museum, March 8 – April 5, 2001, ed. Matthias Waschek (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2003).[/ref]. The ideas of Edmond Picard and Jules Destrée in Belgium, as well as the productions of Gustave Surrurier-Bovy, also fueled debates. Among writers, discussions took place mainly in anarchist journals and within a new circle that in 1896 took the name “social-art group.” Painters with anarchist convictions, such as Signac and Pissarro, were then led to express their own opinions: rejecting the writers’ distinction between “art for art’s sake” and “social art,” they insisted upon the intrinsically social character of their works and upon the emotion likely to be shared with the spectator[ref]See 48/14 La revue du musée d’Orsay, Spring 2001, special issue on Neo-Impressionnism and Social Art.[/ref].

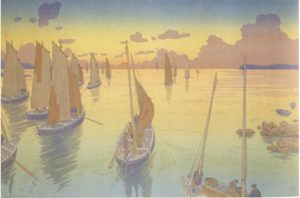

Fig. 2: Henri Rivière, Sunset, color lithograph, 54.5 x 83 cm, no. 11 in the Aspects of Nature series, 1898.

The idea of art as social took on a new orientation at this time. While Saint-Simonism, the Count Laborde report[ref]Count Léon de Laborde, De l’union des arts et de l’industrie, 2 vols (Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1856).[/ref], the philosophy of Hippolyte Taine, and Viollet-le-Ducian rationalism remained major references, English and Belgian models now took on decisive weight. Proposals in the area had a clear reformist ring to them. In 1894, Gustave Geffroy launched the idea of a “Night Museum” whose purpose would be to train art workers. The People’s Society for the Fine Arts, created in 1894, organized lectures and sought to be a tool of social cohesion by bringing artists together with a varied public. After the museum and the association, it was the decor of daily life that became invested with educative power. The architect and art critic Frantz Jourdain advocated “art in the streets” and the involvement of artists in the utilitarian decoration of the public way[ref]Frantz Jourdain, “L’art dans la rue,” Revue des Arts Décoratifs, 12 (January 1892): 211-14.[/ref].

Fig. 3: Alexandre Charpentier, The Bakers, bas-relief in glazed brick, executed by E. Muller, 1897. Paris, Scipion Square.

As for Roger Marx, he shifted the discussion into the classroom and launched a campaign in the press in favor of “art in the school.” These men wished to promote a modern, rational, and French form of art in places open to the view of the people and of the child. Far removed from historicist, academic, and realist models, this new art [art nouveau] was the work of such artists as Henri Rivière and Alexandre Charpentier. (Figs. 2 and 3) Moreover, such proposals required the support of public powers, which alone could direct plans along a common path and provide financing for projects. Nonetheless, the state authorities remained barely open at all to these new ideas. In the area of public housing, however, the Siegfried Law of 1894 testified to a change in thinking: the promoters of workers’ housing recognized the need to appeal to the State in order to house society’s poorest members[ref]Roger-Henri Guerrand, Prolétaires et locataires. Les origines du logement social en France 1850-1914 (Paris: Editions Quintette, 1987).[/ref]. Architects gradually became aware of the social role they could play. The creation of the Art in Everything group at the end of the 1890s is an emblematic example of this trend[ref]Rossella Froissart-Pezone, L’Art dans Tout. Les arts décoratifs en France et l’utopie d’un Art nouveau (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2004).[/ref]. Bringing together decorators and architects, the group fought in favor of a genuine social project and a rationalist aesthetic, offering in particular furniture and furnishing sets for the middle class.

Art and Democracy

The years between 1898 and 1901 mark a transition toward new cultural practices. The Dreyfus Affair confirmed the overriding necessity of education, while talk about degeneracy, the bankruptcy of elites, and fear of the crowd became more prevalent. It was in this context that the People’s Universities movement was created. The architecture and industrial arts shown at the Universal Exhibition of 1900 allowed one to draw up at the same time an assessment. What the Exhibition revealed especially was the lack of unity and of social import in French decorative art. Politicians, critics, and artists turned their backs on this vast bazaar, and debates among them then intensified. The French State was now being strongly called into question. With the political pole removed, social-art initiatives were able to bring together writers, intellectuals, artists, and critics.

Fig. 4: Georges Auriol, Cover of the review Les Arts de la vie, Gabriel Mourey, editor, 1905.

The objective was no longer the democratization of art but, rather, cultural democracy. This change ended up rehabilitating popular culture and revising established hierarchies. The commonly-held idea was now to bring art to the people through popularization, exhibitions, and long-term projects. In the enthusiasm surrounding the 1901 law on associations, many new societies were formed: Aesthetics, The College of Modern Aesthetics, Art for All, New Paris, and the International Society for People’s Art and Hygiene, not to mention the many societies founded in the area of public housing. Often international in scope and advocating decentralization, these associations were a direct response to the inefficiency of governmental policy. Among the personalities dominant in this movement, we may mention the names of Maurice Leblond, Louis Lumet, Henri Cazalis (who wrote under the pseudonym “Jean Lahor”), Frantz Jourdain, and Gabriel Mourey. (Fig. 4) Some were clearly socialist in their leanings; others, such as Cazalis, were terrified by the tasteless crowds and wanted to create an “art for the people” that would safeguard learned culture while also letting in old popular French stock. In addition to these predominant figures, we find again and again the same personalities in the investigations undertaken and the associations formed: Gustave Geffroy, Octave Mirbeau, Roger Marx, André Mellerio, André Fontainas, and Georges Moreau. Among the artists involved in these groups, let us mention Charles Plumet, Louis Bonnier, Léon Benouville, Auguste Rodin, Eugène Carrière, Georges Auriol, Henri Rivière, Adolphe Willette, Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, Pierre Roche, Albert Besnard, Alexandre Charpentier, and Théophile Alexandre Steinlen.

Fig. 5: Jules Lavirotte, Working-class detached home, Paris Home Show, 1903.

Social art, which was now integrating ideas from sociologists and economists, then set its focus on certain “sites”:

– the development [cité], the street, and the home: whether one’s writings and initiatives bore on low-cost housing, the planned town [la cité-jardin], or urban policy [l’urbanisme], many attempts were made to integrate modernity into an urban setting. The public way was thenceforth conceived in a functional way: it was to incorporate, in particular, the park for leisure time and the community hall for meetings, as well as a library and a museum for education[ref]Gustave KAHN, L’Esthétique de la rue, Paris, E. Fasquelle, 1901 ; Georges BENOIT-LÉVY, La Cité-jardin. Préface par Charles Gide, Paris, H. Jouve, 1904.[/ref]. (Fig. 5)

– the domestic space: the idea was to decorate and furnish the most modest home, at the lowest possible cost, in line with a logic of rationality, hygiene, and aesthetics. On the level of style, the promoters of this new art of decoration defended a simplified and “Frenchified” Art Nouveau aesthetic compatible with industrial production.

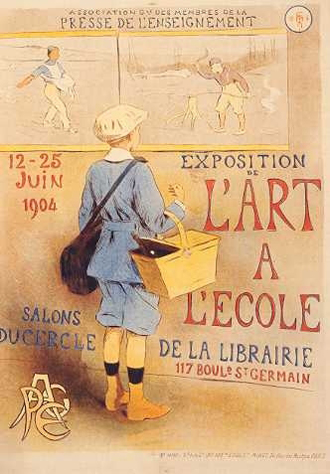

Fig. 6: Etienne Moreau-Nélaton, Poster from the Art in the School Show, 1904, color lithograph, 140 x 103 cm. Paris, French National Library, Print Department.

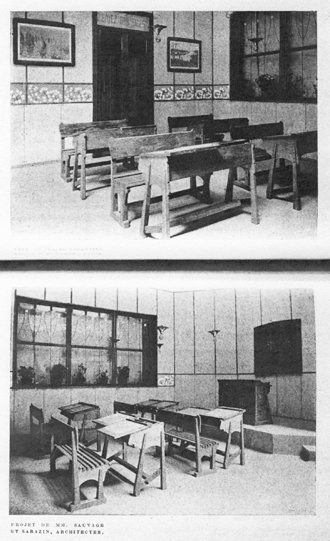

– the school: it was a matter of introducing into schools the latest advances in pedagogy and psychology as well as a “hygienic aesthetic”–one that would be clear, simple, natural, rational, and patriotic on the symbolic level. (Fig. 6)

With neither the necessary financial means nor the desired level of recognition, these tiny associations nevertheless struggled to initiate reforms. Moreover, there was no dearth of opponents of cultural democracy. Camille Mauclair and groups like the Old-Paris Commission denounced the utopian thinking and radicalism of such proposals.

French Synthesis and Institutionalization of Social Art

With the end of the Dreyfus Affair, the winding down of the People’s Universities movement, and an unprecedented wave of strikes, the alliance that had united intellectuals, artists and the popular classes started to come apart after 1906. On the artistic scene, Art Nouveau drew its last breaths and the threat of foreign competition redirected talk toward the national tradition and classicism.

Social art, as the ephemeral reappearance in 1906 of a review bearing this title testifies, remained, for a portion of the older generations as well as for the new ones, an ideal to be achieved. It was no longer envisioned as a popular art but, rather, as a concept liable to be operative in a democratic, industrial society.

Fig. 7: Henri Sauvage and Charles Sarazin, Project for a classroom, published in Ch. Couyba et al., L’Art à l’Ecole (Paris: Bibliothèque Larousse, [1908]), p. 50-51.

The year 1907 witnessed the creation of two major societies, the National Society for Art in the School and the Provincial Union of the Decorative Arts. Both groups were chaired by Senator Charles Maurice Couyba. The objective of the first one was “to get the child to love nature and art, to make school more attractive, and to aid in the education of taste and in the development of the moral and social education of youth.”[ref]Charles Maurice Couyba et al., L’Art à l’école (Paris: Bibliothèque Larousse, no date [1908]), p. 125.[/ref](Fig. 7) The goal of the second one was to “foster and carry out artistic and industrial decentralization by building back up regional industries and crafts.”[ref]L’Art et les métiers, November 1908: 23-26.[/ref] These societies were headed up by senior civil servants and politicians who had at their disposal the power required to initiate reforms. They were going to carry all the more weight as successes abroad began to exert an alarming amount of pressure around the years 1908-1910.

It was in this context that Roger Marx, a member of the National Society for Art in the School, launched the idea of an international exhibition of social art.[ref]Roger Marx, “De l’art social et de la nécessité d’en assurer le progrès par une exposition,” Idées modernes, 1 (January 1909): 46-57; “L’art social,” in L’Art social (Paris: E. Fasquelle, 1913), pp. 3-46.[/ref] Here, he was taking back up a proposal first put forth by Couyba in 1907. Nevertheless, the expression social art was not chosen by accident. The point was to leave a mark on people’s minds and to create a healthy new burst of energy. The point was also to place the vague reformist efforts of the abovementioned groups within a French tradition that stretched from Saint-Simonism to Henri Cazalis, passing by way of Count Laborde, Proudhon, and Jean-Marie Guyau. On the political level, Roger Marx’s positioning was that of a radical solidarism whose aim was to achieve social cohesion and whose belief was in State action. In fact, this social art, defined as a kind of art that “is intimately involved in the existence of the individual and the community,” was no longer addressed only to the “fourth estate” but also to society as a whole. In his proposals, Roger Marx thus offered a synthesis of a large portion of the ideas that had been put forward since 1900.

Politicians and the main artistic groups rallied to this project of setting up an exhibition. The proposal gradually gained the status of a true consensus.[ref]G.-Roger Sandoz and Jean Guiffrey, Exposition française. Art décoratif Copenhague 1909, General Report preceded by a Study on the Applied Arts and Art Industries Exhibitions (Paris: Comité français des expositions à l’étranger, no date).[/ref] As for the idea of “social art,” it ultimately federated all those who dreamed of an art that would be both modern and French, despite a well-known set of reservations: the national, elitist, decorative tradition, nostalgia for the corporatism and patronage, as well as artists’ own individualism.

The war swept away the promises to which this project had given birth. The idea of social art was to remain present in people’s memories. To take one example, the 1934 manifesto of the Union of the Modern Arts contained this short and simple phrase: “modern art is a genuinely social art.”

Bibliographie

Aron. Paul. Les Ecrivains belges et le socialisme 1880-1913. L’expérience de l’art social, d’Edmond Picard à Emile Verhaeren. Brussels: Labor, 1985.

Cazalis, Henri [under the pseudonym Jean Lahor]. L’Art Nouveau. Son histoire. L’Art Nouveau étranger à l’exposition. L’Art Nouveau au point de vue social. Paris: Lemerre, 1901.

_____. L’Art pour le peuple, à défaut de l’art par le peuple. Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1902.

_____. Les habitations à bon marché et un art Nouveau pour le peuple, Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1903.

Couyba, Charles Maurice. Les Beaux-arts et la nation. Intro. Paul-Louis Garnier. Paris: Hachette, 1908.

Dumont, Marie-Jeanne. Le logement social à Paris 1850-1930, les habitations à bon marché. Liège: Martaga, 1991.

Froissart-Pezone, Rossella. L’Art dans Tout. Les arts décoratifs en France et l’utopie d’un Art nouveau. Paris: CNRS Editions, 2004.

Guerrand, Roger-Henri. Prolétaires et locataires. Les origines du logement social en France 1850-1914. Paris: Editions Quintette, 1987.

_____. “ Les artistes, le peuple et l’Art Nouveau.” L’Histoire, May 1995: 62-67.

Herbert, Eugenia. The Artist and Social Reform: France and Belgium, 1885-1898. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961.

Jourdain, Frantz. De choses et d’autres. Paris: H. Simonis Empis, 1902.

Jumeau-Lafond, Jean-David. “L’Enfance de Sainte-Geneviève: une affiche de Puvis de Chavannes au service de l’Union pour l’action morale.” Revue de l’art, 109 (3, 1995): 63-74.

La Chapelle, A. de. “Un Art nouveau pour le peuple. De l’art dans tout à l’art pour tous.” Histoire de l’art, 31 (October 1995): 59-68.

Marx, Roger. L’Art social. Preface by Anatole France. Paris: Bibliothèque-Charpentier, E. Fasquelle éditeur, 1913.

Needham, H. A. Le Développement de l’esthétique sociologique en France et en Angleterre au XIXe siècle. Paris: Honoré Champion, 1926.

Tolstoy, Leon. Qu’est-ce que l’art ? Translated from the Russian. Intro. Teodor de Wyzewa. Paris: Perrin, 1898.

Catherine Méneux is completing her doctoral dissertation in Art History on “Roger Marx (1859-1913), Art Critic” at the University of Paris-IV. She has curated, directed, and co-edited catalogues for the following recent exhibitions: Roger Marx, un critique d’art aux côtés de Gallé, Monet, Rodin, Gauguin . . . (Roger Marx, an art critique alongside Gallé, Monet, Rodin, Gauguin . . .; Nancy: Arts Lys, 2006, organized in partnership with the Orsay Museum) and Critiques d’art et collectionneurs Roger Marx et Claude Roger-Marx 1859-1977 (Roger Marx and Claude Roger-Marx, art critics and collectors, 1859-1977; Paris: Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art, 2006). As an accompaniment to these shows, Méneux organized a colloquium and a one-day conference, Autour de Roger Marx 1859-1913, critique et historien de l’art (On the critic and art historian Roger Marx, 1859-1913) at the Museum of Fine Arts in Nancy and the French National Institute of Art History in Paris in 2006. She currently teaches at the University of Paris-I (Plastic Arts and Art Sciences Department) and at the French National Furnishings school. With a master’s degree in Economic Sciences (University of Paris-II), and after having collaborated in the preparation of the Paris-Brussels/Brussels-Paris exhibition (Paris and Gand, 1997) as well as worked for several years in the Parisian art market, she published La magie de l’encre. Félicien Rops et la Société internationale des aquafortistes (1869-1877) (The magic of ink: Félicien Rops and the International Society of Etchers, 1869-1877, exhibition catalogue; Paris: Pandora, 2000). For the French National Institute of Art History, she inventoried the Claude Roger-Marx Archives in 2003-2004. Her research interests bear on social art, art criticism, and artists’ societies, as well as the history of the graphic arts.