We already knew the role the Armory Show of 1913 had played in the transatlantic exportation of European modernity. At the initiative of artists themselves, a number of foreign painters were able to achieve recognition in America as precursors of modernism. Cézanne in particular benefitted from the wave of exportation of French Impressionism before coming to embody a model of the autonomous artist who is not subject to any movement.

Before that time, and as early as 1870, the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel had presented works by Monet and Pissarro for the first time in his gallery on New Bond Street in London, where the only kind of foreign art then admired belonged to the Barbizon School. In fact, the Impressionists had as much trouble gaining acceptance in England as they did in France. Pissarro, for example, complained in 1871 of the inhospitableness of the English as well as of his colleagues’ rudeness, indifference, and selfish jealousy. And yet, for modern painters to become established in England, all that was needed was a few decades, during which time a high-quality speciality press developed and some inspired critics emerged. In the meantime, the case of England–though the phenomenon was still more pronounced in Germany–shows to what extent the history of art intersects with questions of identity. The issue of nationality had quite an influence, especially for opponents of modernity who saw modernism as part of a betrayal of the national consensus. In her thesis on Cézanne’s reception abroad, Laure-Caroline Semmer has reconstructed these stakes, showing to what extent the painter was instrumentalized by all sides in support of the most contradictory causes.

While Cézanne himself was hardly a strategist, except in the area of his passion, other artists were more aware of the stakes involved in their careers. This is one of the favorite topics explored by Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, who studies the ways in which the various forms of Paris avant-garde painting between 1855 and 1914 became internationalized. Her sociological approach leads one to open one’s eyes about how a detour abroad helped artists who did not always enjoy full legitimacy at home. This is bound to remind one of Daniel Buren’s own long listing, in his Écrits, of the voyages he undertook between September 1978 and July 1979. The following entries are just the start:

Paris–New York: September 14, 1978

New York–Halifax (Canada): September 25, 1978

Halifax–Montreal: October 2, 1978

Montreal–New York: October 5, 1978

New York–Philadelphia: October 18, 1978

Philadelphia–New York: October 19, 1978

New York–Paris: October 20, 1978

Paris–Cologne: October 23, 1978

Cologne–Paris: October 25, 1978

Paris–Liège: October 26, 1978

Liège–Paris: October 26, 1978

Paris–Zurich: November 1, 1978

Zurich–Milan: November 2, 1978

. . . Etc.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of June 22nd 2006

Laure-Caroline SemmerBirth of the Figure of the Father of Modern Art:

Cézanne in International Exhibitions 1910-1913

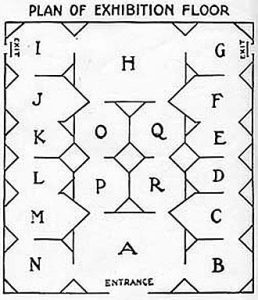

Armory Show, 1913, New York, floor plan of the exhibition and distribution of the works of art by gallery. Gallery A: American sculpture and Decorative Art. Gallery H: French paintings and Sculpture. Matisse, Denis, Vuillard, Bonnard . . . Gallery G: English, Irish, and German paintings and drawings. Kaninsky, Walter Sickert . . . Gallery E: American paintings. Walt Kuhnt, Arthur B. Davies. Gallery I: French paintings, watercolors and drawings. Matisse, Picasso, Redon, Puvis de Chavanne. Gallery P: French, English, Dutch, and American paintings. Albert Pinkham Ryder, Daumier, Delacroix, Théodore Rousseau, Monticelli, Puvis de Chavannes . . . Gallery O: French paintings. Mary Cassatt, Degas, Manet, Pissarro, Renoir, Seurat, Sisley, Toulouse-Lautrec. Gallery R: French, English, and Swiss paintings. Gauguin, Picasso, Puvis de Chavannes, Augustus John. Gallery Q: Cézanne + Van Gogh.

It was at the initiative of artists themselves that the construction of Cézanne as the father of modern art made its appearance. In France, the painter was for a time affiliated with Impressionism, but no critic close to that movement had made up his mind to support him. For Joris-Karl Huysmans to deign to devote a few lines to him in Certains, for example, Pissarro had to have recommended him repeatedly. And yet, beyond France’s borders, the image of Cézanne as the father of modern art was soon born. This paternity granted to Cézanne emerged during the first three major international exhibitions of modern art, the Sonderbund in Cologne, Roger Fry’s two exhibitions at the Grafton Galleries, and the first Armory Show of New York in 1913.

Impressionism as Francophobe Tool

Germany was the first country to welcome Cézanne’s work within its national collections, thanks to the buying policy of Hugo von Tschudi. As early as June 1897, von Tschudi introduced the first Cézanne purchased from Paul Durand-Ruel (Mill on the Couleuvre at Pontoise) into the National Gallery in Berlin. This event quickly took on an exemplary value for Impressionist critics. A few years after the scandal of the Caillebotte bequest and in a climate of pure political hatred between the two counties, von Tschudi’s step was considered to be a forceful act in favor of modern art. And yet the nationality of most of the Impressionist artists bought by Tschudi did not escape the notice of Emperor Wilhelm II, who was inclined to support propagandistic art dedicated to the Hohenzollerns. Using art for nationalist ends and advocating art for the German people, the Emperor, a fierce Francophobe, was an opponent of modern art and used it to illustrate the deviancies of the French mind, as in the following speech from 1901:

“The grand ideals have become for us, the German people, enduring values, whereas for other peoples they have more or less been lost. There no longer remains anyone but the German people, who are in the first ranks of those called upon to keep watch over these grand ideals, to cultivate them, to pursue them.”[ref]Wilhelm II, “Ansprache zur Einweihung des Siegesallee” (January 18, 1901), translated into French and reprinted in Paris-Berlin. Rapports et contrastes France-Allemagne (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1978), p. 726.[/ref]

Paul Cézanne, Mill on the Couleuvre at Pontoise, 1881, Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

Thanks to von Tschudi’s audacity in presenting Impressionist works as gifts to the crown, the Emperor accepted them so long as they were not visible. But in his attempt to offer these works a central location in the museum’s galleries, the museum director completely reorganized the hanging. Influenced by certain members of the Berlin aristocracy and after a misunderstanding with Tschudi, the Emperor ordered these works taken down and forced the resignation of the museum’s director in 1908.

Cézanne, Expressionist Painter: The Sonderbund of Cologne

On May 24, 1912, the fourth and most famous Sonderbund opened in Cologne. At the start, the Sonderbund was a nonprofit organization founded in 1909 whose goal was the promotion of modern art, especially French art, within exhibitions that brought modern artists together with young German artists. Already during the second Sonderbund event, which was entitled “Deutsche und Französisiche Kunst,” Cézanne was represented by a few watercolors, but especially three of Braque’s canvases from 1908 were exhibited, thereby affirming already that the Cézanne’s posterity was to be found in the main among those whom he had influenced.

On account, among other reasons, of a separation of the art by nationality, five concentric halls at the heart of the exhibition presented one-hundred-and-twenty-five works by Van Gogh, twenty-six works by Cézanne, twenty-five of Gauguin’s pictures, and sixteen works by Picasso in particular, along with the German artists August Macke, Paul Klee, and Karl Hofer. On this occasion, the emergence of the triumvirate of modernity–Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin–testified to a glorification of individuality that was to mark the history of modern art and its exportation. It was no longer a matter of showing movements but, rather, individualities who took part in these movements. Moreover, immediately, a cultural adaptation took place: in Germany, Cézanne became the precursor of Expressionism.

Cézanne as Leader: The Grafton Galleries

On November 8, 1910, the Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition opened at the Grafton Galleries. In the context of England, which was inclined to welcome the Impressionists but not yet ready to recognize the upheaval of modernity and the various avant-gardes, the show organized by Roger Fry in 1910 was of key importance. Again, the nationality of the majority of the artists or of their dealer was going to be an occasion for debate.

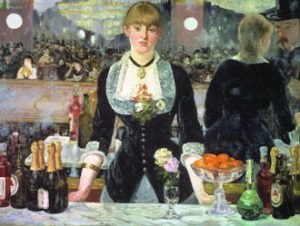

Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-1882, London, Courtauld Institute Gallery.

Shortly before this exhibition began, the Exhibition of the Works of Modern French Artists presented a number of French works at the Public Art Gallery of Brighton under the leadership of Robert Dell. Reactions to this show dedicated to French painters were lively. For a few years already, the regular recognition and celebration of French art had been perceived as an attack on England’s young creative artists. Also, in direct reaction to this French supremacy, which had been reinforced by Fry’s show, the exhibition Septule and Racinists opened in December 1910 at the Chelsea Art Club, presenting only English artists. However, as in the case of Germany, the “modern” organizers supported artistic expressions from France without insisting on the nationality of the artists, preferring to defend the idea of a large international modern school.

Paul Cézanne, Hortense Fiquet in a Striped Skirt, 1877, Boston, Museum of Fine Arts.

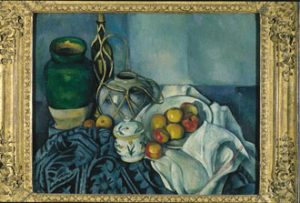

Paradox is at the heart of the very organization of Fry’s exhibition. The entrance into the room and the show’s title affirmed the superiority of modernity and the paternity granted to Manet. Yet Fry placed at the beginning, just opposite the Bar aux Folies Bergères, two Cézanne canvases–a still life and his Hortense Fiquet in a Striped Skirt–so as to underscore Cézanne’s advance in the modern adventure. The first room presented all the Cézannes, twenty-one in number, opposite eight Manets. The numerical supremacy of Manet’s three “heirs” undermined Manet’s own importance in the emergence of the movement. On the other hand, the presence of Cézanne, proposed as central, and the visual similarities between these three painters–Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh–offered this position to the painter from Aix. The arrangement of the exhibition displayed a sort of lineage, with Cézanne appearing as the pivot between Manet and the Post-Impressionists. In reality, Cézanne in 1910 had not yet gained recognition in England. In proposing Manet as the leader in this demonstration of modernism, Fry was choosing an artist who had by then become entirely institutionalized. Cézanne received, moreover, a quite lukewarm reception. As a critic like Sir William Blake Richmond wrote, “Cézanne mistook his vocation; he should have been a butcher.”[ref]Sir William Blake Richmond, “Post-Impressionist,” Morning Post, November 16, 1910: 5.[/ref]

Paul Cézanne, Still Life with Apples, 1893-1894, Parisian collection.

On October 5, 1912, the second exhibition Fry organized at the Grafton Galleries opened its doors. The impact of the first show had fostered the gradual acceptance of a Post-Impressionist reading. This reading was reinforced by Cézanne and Gauguin in November 1911 at the Stafford Gallery. Within the selection made by Fry, Cézanne was affirmed as the father of the new school, thus dethroning Manet. The balance of the exhibition was completely different, since Gauguin and Van Gogh were themselves represented only with some lithographs (except for one Van Gogh canvas), whereas Cézanne appeared through twenty-five canvases and five watercolors.

The exportation of Cézanne paintings to America was determined by one other special feature. It was not the Impressionists, nor even Van Gogh and Gauguin, who were perceived as innovators, but, rather, the artists of the new generation.

Cézanne as Mentor [maître à penser]: The New York Armory Show

Armory Show, 1913, New York, view of Gallery Q.

The Armory Show opened its doors for the first time in New York on February 17, 1913. It would then move in part to Chicago and Boston. Organized by the artists Walter Pach, Walter Kuhn, and Arthur B. Davis who had discovered Cézanne’s work thanks to their time spent in Paris and to their regular visits to the Steins’ apartment, as well as to Matisse, some of whom had frequented his academy, the exhibition followed the model of the Cologne Sonderbund and Fry’s shows. More than 1,600 works were exhibited, again divided up by nationality and still according to a subjective process. Van Gogh, in particular, was presented as a French artist.

Gallery Q (one of the four centrally-located rooms) was devoted entirely to Cézanne’s art and to that of Van Gogh. Thirteen works by the master from Aix, one watercolor, and lithographs on loan from Vollard were presented.[ref]Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Modern Art, Chicago, March 24-April 1, 1913 (Cézanne, Paul): loan of Ambroise Vollard: two lithographs, Portrait of Cézanne, Baigneuses, Colline des pauvres, Auvers-sur-Oise, Portrait, and Melun; loaned by E. Druet: La vielle femme au chapelet; loaned by J. Quinn: Portrait of Mme Cézanne; loaned by Mrs. Montgomery Sears: Fleurs; loaned by J. O Summer: Moissonneuse; loaned by Sir William Van Horne: Portrait of Mme Cézanne; loan of Stephan Bourgeois: unknown.[/ref] At the entrance was found the Portrait of Gustave Boyer, the sale price set at $4,000.00.[ref]John Rewald, Cézanne and America: Dealers, Collectors, Artists and Critics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989); on pp. 193-207, Rewald details how Cézanne’s works were presented at the Armory Show.[/ref]

Paul Cézanne, View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph, 1888-1890, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cézanne’s genius no longer required proof in America, as was established with the March 16, 1913 purchase of La Colline des pauvres by the Metropolitan Museum at $6,700.00–the highest price paid in the whole show. This institutional event was decisive for Cézanne’s critical reception. At a time when the avant-garde was creating scandal, its spiritual father was entering into a museum. That it was the Metropolitan Museum that acquired this canvas is not insignificant, in view of the time spent by Roger Fry, Cézanne’s greatest admirer, as chief curator for paintings in 1906.

In these major exhibitions, it was French modernism that was being exported. In the process, it underwent a cultural adaptation whose goal was to show the liveliness of the local modernism in each country. The fact that these three exhibitions were organized at the initiative of artists themselves was not unrelated to this phenomenon. Moreover, the proclamation of Cézanne as the father of modern art affirmed the need to effect a cultural adaptation of this modernism; each time, his critical fortune was, on the whole, similar, while revealing at the same time particular national features. At first, in the early 1900s, Cézanne was exported as an Impressionist. Then, his special place within this same movement allowed him to be removed therefrom so as to make him a precursor thereof as well as an individual genius. In Germany, he became a master of Expressionism, whereas in England, thanks to Fry’s writings, he justified the label of Post-Impressionist, situated between classicism and modernity. In the United States, he became established as the father of modern art, as Alfred H. Barr’s 1936 diagram for the Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition shows. Moreover, when MoMA opened its doors in 1929, it began with Cézanne, whereas France some fifty years later, when the Orsay Museum opened on December 9, 1986, almost ended its selection of works with him. This museographic consideration offers a very different reading of his influence. Through the proximity of works by Matisse, Picasso, the avant-garde, and abstraction, MoMA displayed a history of modern art in which Cézanne existed as patriarch, whereas the presentation of these works in relation to him as a nineteenth-century artist afforded him the place of precursor, alongside the Impressionists, but tended to minimize his impact on later generations.

Bibliographie

J.B. Bullen, Postimpressionists in England, London, New York, Routledge, 1988.

M. H. Brown, The story of the Armory show, New York, The Jospeh H. Hischorn Foundation, 1963.

A.-P. Bruneau, “Aux sources du postimpressionnisme. Les expositions de 1910 et 1912 aux Grafton Galleries de Londres”, Revue de l’art, n°113, 1996, p. 7-18.

P. Cézanne, Correspondance, Paris, Grasset, 1978.

A. Gruetzner Robins, Modern Art in Britain 1910-1914, London, Merell Holberton, Barbican Art Gallery, 1997.

B. Nicolson, “Post-impressionism and Roger Fry”, Burlington magazine, vol. 93, janvier 1951, p. 11-15.

W.B. Richmond, „Post-impressionist“, Morning post, 16 novembre 1910, p. 5.

B. Paul, Hugo von Tschudi und die moderne französische Kunst im Deutschen Kaiserreich, Mainz, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1993.

I. Overbeck, Invented traditions. The cologne Sonderbund Exhibition 1912. Regionalism, Nationalism and Internationalism, MA, Courtauld Institute, 2000.

G. Pène du Bois, “The spirit and the chronology of the modern movement”, Arts and Decoration, mars 1913.

J. Rewald, Cézanne and America, dealers, collectors, artists and critics, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989.

Manet and Post-impressionist, London, Clive Bellantyne, 1910.

Catalogue of the international exhibition of modern art 1913, 3 volumes, New York, Arno Press, 1972.

Paris-Berlin. Rapports et contrastes France-Allemagne, Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1978.

Paris-New York, Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou, Gallimard, 1991.

Laure-Caroline Semmer a soutenu en 2004, à l’Université Paris I, sa thèse sur Cézanne au XXe siècle. Une histoire de la réception critique, dans laquelle elle étudie les modes d’émergence et de déformation des différentes images du peintre, travaillant aussi bien dans les domaines de l’histoire de l’art que de l’histoire des idées, des institutions et de l’histoire politique. Parallèlement à ses études en histoire de l’art, elle a obtenu également une licence d’ethnologie. En 2006, année du centenaire de la mort de Paul Cézanne, elle participe à différents événements, notamment un colloque organisé par le musée Granet. Elle publie également une monographie sur Cézanne aux éditions Larousse.