Annette Becker is known for her fine knowledge of wars and genocides. She is now studying the conditions under which they are being exhibited in museums that have preserved traces thereof. Such museums have become sites of both commemoration and mourning. Especially since the 1990s, a bit everywhere in the world and there, too, things appear as powerful signs of men and women who have disappeared and of what is no longer. And yet, how far can one go in reconstituting historically these minuscule lives pierced by the tragedies of history ?

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Things in Catastrophe Museums

What Sorts of Things ?

Annette Becker

“Things speak to us. . . . They afflict us. . . . They are a sort of language that surrounds us.”

— Pierre Bergounioux [1]

Catastrophe: “A sudden event that upsets the course of things, often while bringing about death and/or destruction. Synon. Disaster, calamity, misfortune.” [2] Our dictionaries are quite adept at handling euphemisms. Back in 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti simultaneously banned war—“Museums: cemeteries! . . . Identical, surely, in the sinister promiscuity of so many bodies unknown to one another”—and exalted it as “the world’s only hygiene.” [3] Artists are always to be taken seriously: on the basis of this “no-future” rhetoric, Marinetti’s compatriots forged the concept of a Museo al aperto to describe spaces where traces of wars, repression, and mass death have become commemorative sites, places for mourning, for a grounding in despair. From the 1990s onward, this national heritagization has gained new breadth in the cyclic return to the two World Wars and to the Shoah (catastrophe in Hebrew) in Western countries, Western Europe, the United States, Australia; to the end of the Soviet Union and its satellites; to new genocides, that of the Cambodians, that of the Tutsi of Rwanda; and, finally, to Islamist global terrorism.

The ruins, restored or left in state, the mass graves, the concentration camps and forced-labor camps, the extermination sites, and the prisons have in turn become museums wherein objects and traces are shown in a fascinating act of self-conscious reflection [mise en abyme].

These sites exist first of all in the heads of those who suffer from their past. They exist in the form of tears and prayers, a landscape, or a topography, whether legendary or not. [4] They are, in short, an interpretation of the trauma that is also a representation thereof. How does one make human beings reappear when everything was done to make them disappear? Such “site museums” are confronted with a taboo, the taboo of death; how does one show this “thing” through things, metaphors of a disappeared life?

What is one to make of the ever-accusatory ruins in these sites that are very high in memorial, emotional, and sacral potential? [5] Most such museum sites are made up of two parts: the sites themselves, which have been more or less rearranged and refurbished in order to render them visitable, and an area where History is displayed in a newly constructed building—the design of which is today often assigned to a major international architect—or in one of the buildings of the time, diverted from its prior function in order to become a museum within the site museum. For, while these memorial museums first of all are real or substitute cemeteries, they also henceforth are included in catastrophe tourism, sometimes not without fostering a sense of voyeurism toward these detestable objects. People now speak of Dark Memory Tourism.

On April 10, 2010, when the plane taking Polish President Lech Kaczyński for the first time to commemorate the Katyn massacre crashed on the very site where the massacre had taken place, one had the feeling that one was living through a remake. As Viktor Yerofeyev said, “For the Poles, Russia is an unbounded Katyn.” [6] Are not all catastrophe sites boundless—first time tragedy, second time farce, and a third time a museum?

Death as Thing

When Vassily Grossman arrived in Treblinka in 1943, the violated bodies—the bodies of the crime of crimes, genocide, a concept invented at the very same moment by Raphael Lemkin—were quite visible:

The soil threw up bone fragments, teeth, various objects, papers. . . . Things burst from the cracked earth, from its still gaping wounds: half-rotted shirts, underwear, shoes, pale cigar cases, watch parts, penknives, shaving brushes, candlesticks, red-tasseled shoes, embroidered towels from the Ukraine, pieces of lace, scissors, dice, corsets, and bandages. Further on, one saw piles of utensils: aluminum tumblers, cups, frying pans, sauce pans, cook pots, jars, tin cans, canteens, vulcanite children’s cups, etc. . . . Thick, wavy hair, the color of copper, . . . then blond curls, heavy black braids against bright sand, and then more hair, and still more.

And yet, at Treblinka, as at most death sites, death remains in large part taboo and is all the more invisible as the way of dying and then time, even denial, have served to make the bodies disappear. At the National September 11 Memorial & Museum in New York, the human remains are sealed within enormous walls, and one literally descends to be amongst the victims yet without ever seeing them.

Conversely, in Rwanda death is on display; bodies are shown. Thus, at the Murambi Genocide Memorial Centre, skeletons have been preserved in lime, positioned just as their bodies were at the moment of killing. The senses—the odor is quite strong—and the sensibilities of visitors are put to a rough test—all the more so as the museum’s mediators are surviving witnesses who have become guides at these sites where they, as genocide incarnated and sometimes bearing visible scars, not to mention the trauma, “tell the story every day.” [7] These men and women are much more than guides: they bear moral witness. [8] “I am a guide because I am a survivor but also because I can do it.” [9]

Dead Things

Everywhere, the wish has been to give the dead back their names, which is the very translation of Yad Vashem. “To them I will give . . . a memorial and a name” (Isaiah 56:5, New International Version). One could add: “I will give you back a face” via objects and photographs.

For, pervasive odors rise up from the apparel on display (piles of shoes from the Majdanek concentration camp; soiled clothing in Cambodia) when the visitors—more than the objects—are not protected by exhibition glass. A preferred choice are the effects of children who were put to death for what they were at the center of the genocide: Rwandan school uniforms, baby booties and bibs at Auschwitz. “All the shoes in the fog of tears have become my mother’s shoes” (Avraham Sutzkever, “Objects,” Vilna ghetto, 1943). For, it is not the objects but human beings that have been “discarded.” [10] Someone’s pair of glasses, this doll, that photograph is unique; it gives an identity back to those who were murdered, like the names etched on Auschwitz suitcases. In Rwanda, the ID cards that are exhibited are proofs of destruction: beneath the photograph and the name, mentions of Twa and Hutu are crossed out; what remains is Tutsi, a synonym for being put to death.

Hiroshima, Museum, Glass case (tricycle, helmet). ©Annette Becker.

As Claude Lévi-Strauss recalls, “The virtue of archives is to put us in contact with pure historicity. . . . Archives are the embodied essence of the event.” [11] This is what museum designers have done in one way or another, from the diversity of the most traditional and most physical sorts of archives to the most virtual ones, up to and including the landscape itself, which can be seen in or around exhibition sites. We are dealing here with full sensorial spaces wherein visitors are given a “kick in the stomach.” Modern museums are the work of museographers who are adept at furnishing the space with written documents, drawings, photographs, objects, presences of absence. Visitors are led to retrace routes as they move around the space, sometimes while undergoing sensorial experiences—like seeing a ditch into which creosote has been poured—that trivialize the past.

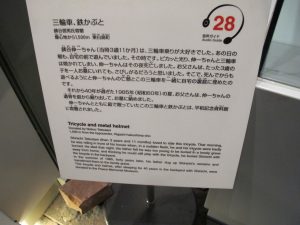

Museum label in Japanese and English. ©Annette Becker.

As “minuscule lives,” tiny objects remain very close to the ways in which they were used by individuals, quite near to their personal experiences. These “things” recount the story of the individual who used them, loved them, hated them, lost them, or found them. “Things created by man in society have a permanent worth and meaning. . . . They will survive death and decay.” [12] Catastrophes bring on death while surviving objects give back life. The closer they are to human beings—drawings, musical instruments, pieces of embroidery—the more one has the impression that one is approaching a trace of those who are absent. Yet too much of an artifact, too much scenography makes them disappear. They belonged only to a single individual and are commonplace enough that everyone in the same group could have possessed the same thing, ever similar, ever different.

Natacha Nisic, Children’s memorial, Shoah Memorial, Paris. 2018. ©Annette Becker.

Objects that were the commonplace property of ordinary lives suit the immediacy of the horror: a bicycle of a murdered son, paired with a text read by his father at the Jewish Museum of Deportation and Resistance in Mechelen; rosaries in the very hands of the praying victims of genocide in Kinazi, Rwanda. At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, commonplace objects have become history to be touched, in both senses of the term to be touched. A schoolboy’s shirt, a sandal, a pipe, a watch, glasses, shoes, a jar. These things sketch the outlines of a personal portrait of human beings caught up in the machinery of death.

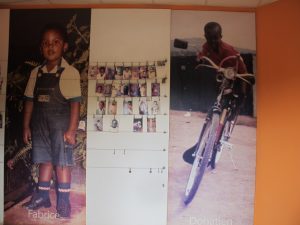

Child victims of Rwanda’s Tutsi genocide, Kigali, Genocide Memorial. ©Annette Becker.

Large objects fulfill another function: they focus one’s gaze and become striking as they communicate a message that both synthesizes and symbolizes the collectivity. Museographers at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. were the first to have placed imposing visual elements in their galleries: a wagon, a boat used by Danes to save their Jews, a Gypsy cart.

“Literature and art make the familiar look strange, the ordinary look beautiful,” says Orham Pamuk of his “Museum of Innocence” in Istanbul—a book that has become a museum, or is it vice versa? In these museums, personal things are archives of life and death, hovering between “estrangement” (Carlo Ginzburg) and “defamiliarization” (Viktor Shklovsky). [13] Like life itself, they are heteroclite as well as sometimes kitschy—like the pink stuffed lamb decked out with blue, white, and red sunglasses that was placed at the temporary memorial set up after the attack in Nice, France, where children were struck by a truck on Bastille Day 2016. As Milan Kundera well knows, “Kitsch excludes everything from its purview which is essentially unacceptable in human existence. . . . . kitsch is a folding screen set up to curtain off death.” [14]—or perhaps it isn’t?

[1]Le Monde, June 9, 2017.

[2]Trésor de la Langue française informatisé, www.atilf.fr

[3]The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) http://www.unknown.nu/futurism/manifesto.html

[4]Maurice Halbwachs, La topographie des Evangiles en Terre Sainte (1941; Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2008).

[5]Annette Becker, “Pour la mort et les ruines, pas de Fin de la Grande Guerre,” in the catalogue Ravaged : Art and Culture in Times of Conflict, ed. Jo Tollebeek and Eline van Assche (Louvain: Museum Leuven, 2014).

[6]Quoted by Piotr Kosicki in Commémorer les victimes, en Europe, XVI-XXIe siècles, ed. David El Kenz and François-Xavier Nérard (Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2011), Postface by Annette Becker.

[7]Magnifique Neza, apropos of the survivor-guides of Rwanda, April 2014.

[8]Avishai Margolit, L’éthique du souvenir (Paris: Climats, 2006).

[9]Site guide, Bisesero, Rwanda, April 2014.

[10]At the “Canada” section of Birkenau: “Laundry barracks, shoe barracks. Piles of various objects that seem intended for the scrap heap. Among this jumble of items, one can make out glasses, prayer books, children’s dolls, photographs, passports, canes, umbrellas” (Simon Laks and René Coudry, Musique d’un autre monde [Paris: Mercure de France, 1948], p.131).

[11]Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (1962; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 242.

[12]Ernst Becker, quoted by Judyta Pawlak in the catalogue Biographies of Things: Gifts in the Collection of the History of the Polish Jews (Warsaw: Polin, 2013), p.12.

[13]Marita Sturken, Tourists of History, Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007.

[14]Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, translated from the Czech by Michael Henry Heim (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), pp. 248, 253.

Selected Bibliography

Becker, Annette. “Vivre par et pour la musique. Simon Laks pendant et après Auschwitz-Birkenau.” In Simon Laks, Mélodies d’Auschwitz et autres écrits sur les camps. Paris: Le Cerf, 2018.

_____, and Stéphane Tison. Eds. Un siècle de sites funéraires, de l’histoire à la valorisation patrimoniale. Nanterre: Presses de Paris-Nanterre, 2018.

_____, and Charles Fordsick. Eds. Tourisme mémoriel, la face sombre de la terre? Mémoires en Jeu, 3 (2017).

_____. “Faire parler les objets? Nice, après le 14 juillet 2016.” Mémoires en Jeu, 4 (2017).

_____. “Les musées des catastrophes, exposer guerres et génocides.” In Delphine Bechtel & Luba Jurgenson. Eds. Muséographie des violences en Europe centrale et ex-Urss. Paris: Éditions Kimé (“Mémoires en jeu” series), 2016.

Gellereau, Michèle. Ed. Témoignages & médiations des objets de guerre en musée. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2017.

Savoy, Bénédicte. Objets du désir, désirs d’objets. Paris: Collège de France/Fayard, 2017.

Annette BECKER, professor emeritus at the University of Paris-Nanterre, has published a large number of texts on the two World Wars and on how these wars have been remembered and occluded as well as on how they have been represented, including by the most contemporary artists. Her most recent works are Voir la Grande Guerre, un autre récit (Armand-Colin, 2014) and Messagers du désastre, Raphaël Lemkin, Jan Karski et les génocides (Fayard, 2018). She runs the Labex project (Presents in the Past) on history museums and “Dark Tourism.”