In 1978, Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden, then the two members of Art & Language, launched a stern attack on a certain type of political contemporary art. Their condemnation can only be understood in a context when yesterday’s utopia transformed into disenchantment. Thus, the two artists ask a question that remain topical, in a world fraught by turmoil and fears: should we, or can we, “ask what art can do?”. For Art & Language, the answer is negative. However, even though its work seems to speak of a total disavowal of political action, that is not entirely the case. This is what Louis-Antoine Mège underlines by replacing the pictural and discursive output of the group within a larger original project, where critical ambition and aesthetic project work in tandem to reshape the outline of a different kind of political art.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Thibault Boulvain

Louis-Antoine Mège « Art for Society ? » Art & Language (England, circa 1979)

“We are nothing unless we are trying to change ourselves as part of the whole.

Art & Language, “Art for Society?”, 1980

In 1978, the group Art & Language, formed at the time by English artists Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden, published a ferocious op-ed against overtly political contemporary art exhibitions1Art & Language, “On the Recent Fashion for Caring”, Art Monthly, no. 20, 1978, pp. 22-23. This is an abridged version of a paper given by Baldwin, Harrison, Pilkington and Ramsden at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1978 as part of the exhibition “Art for Society: Contemporary British Art with a Social or Political Purpose”. In 1980, their journal Art & Language published a new, more developed version, from which we have taken the title “Art for Society”.. From the get-go, they denounced a “‘left-wing art‘”, with no effect other than the perpetuation of “bourgeois democratic domination“, orchestrated by “opportunist monsters, curators and fools” and artists with a disconcerting “intellectual cowardice“. Expunging all utopianism, they answered the rhetorical question “should we ask what art can do?” with “Nothing, without confronting the real mechanisms of domination.“

Created ten years earlier in the orbit of Coventry College of Art, Art & Language quickly became a leading exponent of analytical and linguistic conceptual art, and, in the 1970s, enjoyed considerable transatlantic growth as well as a measure of critical recognition. However, by the end of the decade it had narrowed and the discourse of the remaining members had radicalized: this was due to the energy spent internally thinking about the group, its transformations and internal conflicts, the changing landscape of contemporary art as well as an uncertain economic situation. From an artistic and theoretical approach initially informed by epistemology and analytic philosophy, there followed a period that distanced itself from scientific rigour by adopting an uncompromising stance towards the art world. Parallel to this pamphleteering work, the group reinvested the pictorial medium in an astonishing manner.

These twin dynamics occurred around 1979, which in the United Kingdom saw the crystallization of a long succession of social and political crises. The failure of the left to respond to popular ‘discontent,’ as well as Margaret Thatcher’s rise to power and the establishment of a liberal-conservative government put an end to the revolutionary aspirations inherited from the 1960s. Within this context, the writings and paintings of Art & Language seem, at first glance, to want to avoid the obvious. Preferring caricatural ad personam attacks, ironic distancing and bitter idiosyncrasy, the artists give the impression of a radical disavowal of any political efficacy of art. However, within the duality of the year or “years” 1979, Art & Language, in a gesture that was both provocative and protective, also sought to find the means for a possible personal and political transformation within a rather disconcerting textual and iconic production.

fig. 1: Art & Language, Ils donnent leur sang, donnez votre travail, 1978, collage and gouache on photographic print, 30 x 54 cm, collection Philippe Méaille/Château de Montsoreau-Musée d’Art Contemporain. © Art & Language; Courtesy Philippe Méaille. Photography CRBMC.

Galling contradictions

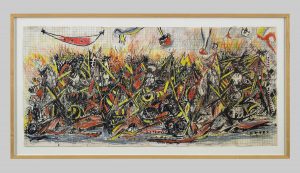

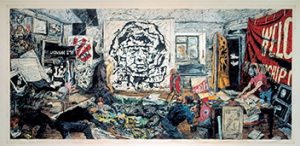

A Vichy propaganda poster hijacked for display in the north of England [fig. 1], an official portrait of Lenin reinterpreted in the manner of Jackson Pollock [fig. 2], and a nervous neo-expressionist touch blurs Courbet’s realism [fig. 3]. It is thus that the paintings of Art & Language, produced around 1979, blur ideological (East/West), political (right/left) and artistic (expressionism/realism) oppositions. In the same way, the numerous and virulent texts of this period pursue these uncertain collisions. Between 1976 and 1985, from the end of the group’s American history to the suspension of the journal Art-Language, Baldwin and Ramsden, sometimes in collaboration with Charles Harrison 2Harrison (1942-2009) was an art historian who worked continuously with the group from the early 1970s until his death., multiplied their writings, the formats used (short, long, referenced), the forms and objects (review of an exhibition or publication, essay, pamphlet, poem), the mediums (their journal, catalogues, art magazines, paintings), revealing an argumentative and rhetorical inventiveness.

fig. 2. Art & Language, Portrait of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock VII, 1980, enamelled paint on marouflaged canvas on wood, 105 x 100 cm, Lisson Gallery (A&L800007), London

© Art & Language; Courtesy Lisson Gallery. Photography Ken Adlard.

Sometimes abstruse and abrupt, these texts testify to a gradual shift from apparent scientificity to polemical verve, almost veering into a strange ‘poetic’ form. Art & Language’s work as lyricists and librettists, in collaboration with the experimental rock band Red Krayola, led by Mayo Thompson 3In addition to the six albums they made with Red Krayola between 1976 and the present day, they wrote the libretto for an unfinished opera, Victorine (1984)., fuelled this new discursive modality. Rhythms, rhymes, figures of speech and lexical luxuriance tend to muffle or even obscure the politically assertive roots of the earlier texts. However, should this be seen as the revival of a debate that would align literary work with the political spectrum, therefore placing stylistic concerns on the right and intellectual content on the left? In other words, do the successive mutations of Art & Language, compelled by circumstances both inside and outside the group, translate a sudden over-politicisation into a definite dizzying ‘stylisation’?

Melancholic mannerism?

Whether being excessive or concise, flirting with the polemical and the decorative, Art & Language takes responsibility for being “engaged in a kind of mannerism“, as a new narrative working against a dominant Western art form. Although this was actually part of a contemporary trend, as evidenced by their participation in the exhibition “Mannerism: A Theory of Culture” in Vancouver in 1982, this position could be seen, in the artists’ own words, as a “reactionary retreat ” indicating a shift towards a politicised style 4Art & Language, La Conférence du Jeu de Paume, Paris, Flammarion/Galerie de Paris, 1996, p. 28.. It’s true that this mannerist gesture, which Art & Language describes as “hinting, parody, travesty, bluffing, forgery, double-talk ” 5Art & Language, “A Letter to A Canadian Curator”, Art-Language, vol. 5, no. 1, October 1982, p. 33., stands in stark contrast to the explicitly political proposals put forward in the “Art for Society” exhibition. The attachment to the duplicity of forms over the pedagogy of substance would confirm the abandonment of any political programme in the spirit of anti-modern suspicion.

fig. 3 : Art & Language, Study for ‘Gustave Courbet’s “Burial at Ornans” Expressing…’, 1981, collage, ink and pencil on paper, 76,5 x 161,5 cm, collection Philippe Méaille/Château de Montsoreau-Musée d’Art Contemporain

© Art & Language; Courtesy Philippe Méaille. Photography CRBMC.

But shouldn’t this be replaced within the vast movement shared by Western leftists who, from 1979 onwards, according to Enzo Traverso’s analysis, confined themselves in a sense of defeat, mourning and melancholy 6Enzo Traverso, Mélancolie de gauche, Paris, La Découverte, 2018, p. 5. ? This might shed some light on the gradual shift in the group’s discursive energy towards a muteness expressed by holding the brush in the mouth to produce large paintings [fig. 4] or by the representation of the studio plunged into darkness [fig. 5]. Somewhere between mannerism and resignation, Art & Language accelerates this entropic trajectory with this terrible admission: “we are all stalked by decadence 7Art & Language, “A Letter to A Canadian Curator”, art. cit.. And yet, despite the fact that in 1979 the only revolution that had taken place was the neo-liberal turn, a light in the dreary horizon of melancholy could be seen, thanks to a game of verbo-iconic artifice.

fig. 4 : Art & Language, Index: The Studio at 3 Wesley Place Painted by Mouth (I), 1982, acrylic, pencil and ink on paper, 343 x 727 cm, collection Herbert Foundation, Gand

© Art & Language; Courtesy Herbert Foundation.

Echoes and gaps

“Athwart, poetics are both of and against their time” 8Henri Meschonnic, Politique du rythme, politique du sujet, Lagrasse, Éditions Verdier, 1995, p. 93 : “Traversière, la poétique est à la fois de ce temps et contre ce temps”.. Following the anachronistic dynamic suggested by Henri Meschonnic, Art & Language’s “reactionary” gesture becomes a poetic tour de force. In other words, within a singular formal experiment – their style – they reconsider the political vitality of a dialogism that has been characteristic of the group since its beginnings. Not only are the texts and the images animated by a great deal of intertextuality and intericonicity, but various discursive and visual strategies attempt to stage a poly-auctoriality (through dialogues, choruses or group portraits) and an address to the public (with a discreet influence of Brechtian distancing).

fig. 5. Exhibition view of a work of Art & Language at the Château de Montsoreau, Index: The Studio at 3 Wesley Place in the Dark (III), 1982, acrylic on canvas, 330 x 780 cm, collection Philippe Méaille/Château de Montsoreau-Musée d’Art Contemporain. © Art & Language ; Courtesy Philippe Méaille. Photography Marie-Caroline Chaudruc.

From then on, style, far from any fixed stylisation, becomes a complex space of echoes and deviations. John Roberts characterises the discursive practice of Art & Language as a writing of noise, delay and disruption 9John Roberts, “The ‘Black Debt’: Art & Language’s Writing”, in Art & Language, Writings, London/Madrid, Lisson/distritocu4tro, 2005, pp. 18-19.. These are all hiatuses that lead us to Déborah Laks’s analysis of these “painters” who return to the “”poetic” to designate a mode of communication specific to painting and to the period that is not of the order of meaning or form but of the ambiguous”10Déborah Laks, “Hans Hartung et les poètes. Réseaux et intermédialité”, in Thomas Kirchner et al (eds.), Hans Hartung et l’abstraction, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2020, p. 55..

As such, Baldwin and Ramsden in no way gave up when faced with a hostile context: they sought to redesign their work so that it was no longer totally on the side of meaning and not quite on the side of form, nor was it the forced march of an idle dialectic or the endless play of signifiers. Instead, it travelled, to quote Laks again, along “the line of the ambiguous”.

This ambiguity of form and purpose, reflected in the polemical style outlined in the introduction, creates a tension between critical ambition and aesthetic program. It is in this uncertain space that Art & Language issues, to quote Valérie Mavridorakis on the subject of this same ambiguity, a veritable “challenge to intelligence” 11Valérie Mavridorakis, “Differences and repetitions. Une sensibilité steinienne dans l’art minimal et conceptuel”, in Cécile Debray and Assia Quesnel (eds.), Gertrude Stein et Pablo Picasso, Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 2023, p. 116.. This challenge gives rise to a wider sceptical enterprise, the political action of which begins, according to Baldwin and Ramsden, by striving “to change ourselves“.

My warmest thanks go to Philippe Méaille and Marie-Caroline Chaudruc (Collection P. Méaille/Château de Montsoreau-Musée d’art contemporain), the Herbert Foundation (Ghent), the Lisson Gallery (London) and the artists, Michael Baldwin and Mel Ramsden, for the kind loan of visuals and permission to publish them.

[1] Art & Language, “On the Recent Fashion for Caring”, Art Monthly, no. 20, 1978, pp. 22-23. This is an abridged version of a paper given by Baldwin, Harrison, Pilkington and Ramsden at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1978 as part of the exhibition “Art for Society: Contemporary British Art with a Social or Political Purpose”. In 1980, their journal Art & Language published a new, more developed version, from which we have taken the title “Art for Society”.

[2] Harrison (1942-2009) was an art historian who worked continuously with the group from the early 1970s until his death.

[3] In addition to the six albums they made with Red Krayola between 1976 and the present day, they wrote the libretto for an unfinished opera, Victorine (1984).

[4] Art & Language, La Conférence du Jeu de Paume, Paris, Flammarion/Galerie de Paris, 1996, p. 28.

[5] Art & Language, “A Letter to A Canadian Curator”, Art-Language, vol. 5, no. 1, October 1982, p. 33.

[6] Enzo Traverso, Mélancolie de gauche, Paris, La Découverte, 2018, p. 5.

[7] Art & Language, “A Letter to A Canadian Curator”, art. cit.

[8] Henri Meschonnic, Politique du rythme, politique du sujet, Lagrasse, Éditions Verdier, 1995, p. 93 : “Traversière, la poétique est à la fois de ce temps et contre ce temps”.

[9] John Roberts, “The ‘Black Debt’: Art & Language’s Writing”, in Art & Language, Writings, London/Madrid, Lisson/distritocu4tro, 2005, pp. 18-19.

[10] Déborah Laks, “Hans Hartung et les poètes. Réseaux et intermédialité”, in Thomas Kirchner et al (eds.), Hans Hartung et l’abstraction, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2020, p. 55.

[11] Valérie Mavridorakis, “Differences and repetitions. Une sensibilité steinienne dans l’art minimal et conceptuel”, in Cécile Debray and Assia Quesnel (eds.), Gertrude Stein et Pablo Picasso, Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 2023, p. 116.

Bibliography

Ansel, Y., “Politique du style”, in Philippe Berthier and Éric Bordas (eds.), Stendhal et le style, Paris, Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2005, pp. 75-89.

Art & Language, La Conférence du Jeu de Paume, trans. by C. Schlatter, Paris, Flammarion/Galerie de Paris, 1996.

Art & Language, “A Letter to a Canadian Curator”, Art-Language, vol. 5, no. 1, October 1982, pp. 32-35.

Art & Language, “Art for Society?”, Art-Language, vol. 4, no. 4, June 1980, pp. 1-25.

Art & Language, “On the Recent Fashion for Caring”, Art Monthly, no. 20, 1978, pp. 22-23.

Hartley, D., The Politics of Style: Towards a Marxist Poetics, Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2022.

Laks, D. “Hans Hartung et les poètes. Réseaux et intermédialité”, in Thomas Kirchner, Martin Schieder, Antje Kramer-Mallordy, (eds.), Hans Hartung et l’abstraction – “Réalité autre, mais réalité quand même”, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2020, p. 36-58.

Mavridorakis, V., “Différences et répétitions. Une sensibilité steinienne dans l’art minimal et conceptuel”, in Cécile Debray and Assia Quesnel (eds.), Gertrude Stein et Pablo Picasso, l’invention du langage, exhibition catalogue, Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 2023 (15 September 2023 – 21 January 2024), pp. 109-116.

Meschonnic, H., Politique du rythme, politique du sujet, Lagrasse, Éditions Verdier, 1995.

Richards, M. & Serota, N. (eds.) Art for Society: Contemporary British Art with a Social Or Political Purpose, exhibition catalogue, London, Whitechapel Art Gallery (10 May – 18 June 1978).

Roberts, J., “The ‘Black Debt’: Art & Language’s Writing”, in Art & Language, Writings, London/Madrid, Lisson/distritocu4tro, 2005, pp. 9-22.

Traverso, E., Mélancolie de gauche. La force d’une tradition cachée (XIXe-XXIe siècle), Paris, La Découverte, 2018.

Antoine Mège is a PhD student in contemporary art history at Sorbonne-Université, working under the supervision of Valérie Mavridorakis. His work seeks to study the transformation, between the 1970’s through to the 1990’s, of the conceptual group Art & Language, via the notion of conversation. Previously he worked as a research assistant at the Documental Institut (dir. Felix Vogel, Kassel), and is now a research fellow at the Deutsche Forum für Kunstgeschichte (dir. Peter Geimer and Georges Didi- Huberman, Paris).