Romain Fathi is a student of the Great War and of commemorative practices. He invites us to reflect on the way in which Australia set up a section for the celebration of the arrival of the Australian and New Zealand Corps (ANZAC) in the Dardanelles in April 1915, a date hallowed as Australia’s birthday. In dismissing the Aborigines and the inglorious period of British colonization, the country constructed an edifying history and endowed itself with a commemorative site in Canberra: the Australian War Memorial (AWM).

This commentary on the AWM collections informs us about all the things used to celebrate the ideal type of the good Australian soldier, deemed bigger and stronger than all others—a guardian of the nation in the most archaic sense of the term.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Romain FathiExhibiting the Great War at the Australian War Memorial:

How the Rejection of Modernity Serves as a Foundation for Sacred Origins

On April 25, 1915, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) —that is to say, the Australian and New Zealand corps of the British Army— landed, along with Allied troops, at Gallipoli, in the Dardanelles. This day was experienced by contemporary Australians as the day of Australia’s birth,1 when their men fought alongside soldiers of the great nations and shed their blood. Raised on Edwardian militarism,2 the population of that era thought that nations were formed in war, and the Great War constituted the opportunity to establish a national narrative that would set aside both the Aboriginal Peoples and the British colonization effort, which had used the island as a penitentiary. Australia was finally going to be able to write a history of which it could be proud, and one about which it still boasts today, through a major series of memorial policies3 whose effect was to derealize the Great War while heroicizing the Australian soldier.

1. Main courtyard of the Australian War Memorial and its Pool of Reflection, a memorial fountain. Photo: Romain Fathi.

In order to immortalize the war of 1914-1918 as its founding event, Australia set up a section whose mission was to collect traces of its engagement in the conflict.4 Everything was scrupulously gathered, recorded, and indexed: photographs, war diaries, writings, orders, film archives, war trophies, and other evidence of the Australian presence in the conflict were repatriated to Australia. The objective at the time was to create a national museum to commemorate the dead and to create a permanent exhibition of the Great War: the Australian War Memorial (AWM). This Memorial was to be built in the capital, Canberra —which, at the time, had not yet risen from ground. It was also a matter of showing the War in a country that had been protected by its distance from the conflict. After a few exhibitions in Melbourne and Sydney that presaged the permanent one and following numerous delays, the War Memorial opened its doors in 1941.

Regulated by an act of Parliament, the AWM was a government-financed institution from its inception.5 Initially designed to commemorate the dead of World War I and to present Australian troops’ engagement in the conflict via a museum located back home, the Memorial saw its statutes modified during World War II so that it might also take on the responsibility of commemorating all subsequent conflicts. Now, this new mission was rendered difficult by the fact that the solider corps were located at the other end of the world, Australian soldiers who died during the Great War not having been interred in Australia.6 At the end of the conflict, the mourning of families was all the more trying as these families could not go and grieve at the graves of the deceased; making a pilgrimage to the burial grounds was financially impossible for the great majority of those who had lost a loved one.7 The Memorial was therefore meant to be a substitute site.

2. One of the stained-glass panels from the Memorial’s Hall of Memory, executed by Nappier Waller. Photo: Romain Fathi.

Among all its commemorative arrangements, such as the memorial fountain, the Hall of Memory, and the plaques listing the names of soldiers, it was really the museum’s galleries that best fulfilled its commemorative purpose. These collections represented the Australian soldiers of the Great War and illustrated what Australians themselves call the Anzac legend. In order to recruit volunteers and to justify engagement in the conflict when the nation itself was divided, war propaganda at the time orchestrated the fabrication of an ideal type of the Australian soldier, and it is this ideal type that is still presented at the AWM and that constitutes the Anzac legend.8

According to this legend, the Australian solider was bigger, stronger, and better than other soldiers, since the climate of his country and his environment were said to have made him a born warrior. Egalitarian, he took care of his fellow soldiers and proved resourceful in any situation. The list of his qualities, which were often far removed from reality (as the historiography of the War has demonstrated), did not serve only for mobilization purposes and for the maintenance of morale and of the population’s war effort.9 Indeed, the Anzac legend and their epic battles were transformed into a dominant national narrative from the start of the conflict.

In order to embody this legend, as early as the 1920s the Memorial commissioned from numerous artists paintings, statues, stained-glass windows, and even scale models that were intended to provide a narrative for the objects collected and to offer a positive view of the conflict. Whereas, through this same conflict, Europe had broken from a positive representation of heroic, male-dominated war, that of the upright body,10 Australia saw in this conflict the chance to construct its own origins narrative and to effect almost an artistic counterrevolution in order to represent it. War-torn Europe produced Otto Dix, Fernard Léger, Paul Nash, Christopher R. W. Nevinson, and many others, as well as the incomparable contributions they made to art. For its part, the Memorial commissioned and demanded classical, nay hackneyed, and martial forms of expression. It thus set the tone for the representation of the Anzacs in Australia.11 The Great War became the Australian Iliad, which had to be represented in such a way as to respect certain canons suitable for the foundation of a national narrative. The pictures were therefore those of great battles, the statues represented idealized, muscular bodies, and the dioramas showed a derealized war dating from another era.12

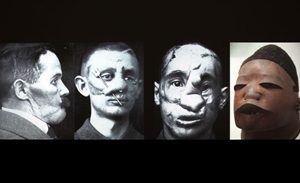

Indeed, while the permanent collections of the Australian War Memorial devoted to the Great War are remarkably well done, for a European visitor they represent much more the wars of the nineteenth century than the kind of modern and industrialized war that took place during the Great War. For, the body cannot withstand the shell. Yet the Australian soldier was taken to be a hero, and, in order to represent him as such, many aspects of the War were left untold so as to be able to show a glorious war that had no impact on the bodies of the Anzacs. It is understandable that this was the method of exhibition chosen at the end of the War for a Memorial that was to be visited by grieving families. Nevertheless, still today, the collection is not set in historical context as a construction aimed at establishing a national narrative, whereas the archives are clear on this score.13 In summary, as much on the level of the fighting and its consequences as on the level of its artistic representation the radical turning point experienced by the European belligerents was repudiated by the official Australian authorities in order to establish a national narrative.

3. The Australian War Memorial’s Roll of Honour commemorating each Australian who died in war. Photo: Romain Fathi.

Established in the nineteenth century, the European formula for the modern nation —one endowed with an Ossianic bard and therefore with a thick and ancient history14— was applied by Australia a century later to create for itself its own origins. Nevertheless, the modernity of the Great War does not lend itself to this classical exercise and reality ends up being warped. At the Australian War Memorial, the traumas of wars have no place, nor do venereal diseases, and still less any degrading injuries. The industrial and technological dimensions of war are set aside so as to highlight the qualities of the heroic and chivalrous Australian soldier, qualities that are summoned up in order to define national values. Placed in the service of the creation of this identity, an identity that was much more imagined than actually lived, art had to evacuate the modernity of the conflict by emphasizing Apollonian bodies drawn after the fashion of nineteenth-century heroic military painting, with some classical references and references to Antiquity added thereto. Indeed, Gallipoli, located near the ruins of Troy, as well as Australian military engagements in the Middle East and the stationing of Australian troops in Egypt in 1915, allowed Australia to be incorporated into the history of humanity and thereby to be ennobled.

Today, the AWM is Australia’s most visited museum and continues to influence the tone of the country’s military history. While the Anzac legend began to wane in the late 1950s and was significantly challenged during the Vietnam War, it has been given new political vigor and has been brought up to date starting in the late 1980s. Since the time of the Howard government (1996-2007), it has again become the dominant national myth, leaving little place for the Aboriginal Peoples and “new Australians” from Asia or Europe who have no roots within White Protestant British monarchist Australia. And even within this group, the Anzac legend ultimately leaves little place for women. At the dawn of the centenary, this quite popular “civil religion”15 offers impressive commercial opportunities for an Anzac industry that is teeming with ideas for hawking the legend16 in a highly patriotic, even nationalistic climate.17

These sacred origins and the combatants themselves will therefore be celebrated with great pomp during this centenary celebration wherein Australia seems very well to be in the lead in the public and private commemoration-related spending race.18

Notes

1 Martin Crotty, “25 April 1915: Australians Troops Land at Gallipoli: Trial, Trauma and the ‘Birth of the Nation,’” in Turning Points in Australian History, Martin Crotty and David Roberts, eds (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2009), p. 113.

2 Henry Reynolds, “Are Nations Really Made at War?” in What’s Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History, Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, eds (Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2010), p. 32-36.

3 Romain Fathi, “La Grande Guerre de l’identité nationale: mémoire, politique et politiques mémorielles en Australie des années 1980 à nos jours,” in Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains (forthcoming).

4 The archives of the Australian War Records Section are preserved at the Australian War Memorial under the call number AWM224.

5 See The Australian War Memorial Act of 1980, which incorporated previous versions of the Act.

6 Apart from General Bridges, buried in 1915, and the Unknown Australian Soldier, in 1993.

7 Bruce Scates, Return to Gallipoli: Walking the Battlefields of the Great War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 64. On the issue of grieving and distance, see: Bart Ziino, A Distant Grief: Australians, War Graves and the Great War (Crawley, W.A.: UWA Press, 2007).

8 On this ideal type, see Graham Seal, Inventing the Legend: The Digger and National Mythology (Queensland: University of Queensland Press, 2004) and Dale Blair, Dinkum Diggers: An Australian Battalion at War (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2001).

9 To get a handle on this historiography, one may refer to the notes and works referenced in Craig Stockings, ed., Zombie Myths of Australian Military History (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010) or Craig Stockings, ed., Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History (Kensington, NSW: NewSouth Pub., 2012).

10 Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, Combattre. Une anthropologie historique de la guerre moderne (XIXe-XXIe siècle) (Paris: Seuil, 2008), p. 275.

11 I am thinking of the writings of Bowles, Coates, Gilbert, McCubbin, as well as Septimus Power. Dryson is a notable exception, but his most original works are not presented in the permanent collections.

12 Romain Fathi, Représentations muséales du corps combattant de 14-18. L’Australian War Memorial de Canberra à travers le prisme de l’Historial de la Grande Guerre de Péronne (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2013), especially chapters 2, 3, and 4.

13 Ibid., p. 27.

14 Anne-Marie Thiesse, La Création des identités nationales. Europe XVIIIe-XIXe siècle (Paris: Seuil, 1999), p. 43 and passim.

15 Kenneth Inglis, Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (1998; Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2008), p. 433 and passim.

16 James Brown, Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession (Collingwood: Redback, 2014), p. 17.

17 James Curran, The Power of Speech: Australian Prime Ministers Defining the National Image (2004; Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2006), Chapter 6, pp. 316-56.

18 James Brown, op. cit., p. 20.

Below, a very brief bibliography offering a few points of access to a quite vast field of investigation, that of Australian identity and its connection with the Anzac. Organized by themes, this general survey suggests a few key books and articles that will allow access to more thematic and much more substantial bibliographies.

Australia During the Great War

BEAUMONT Joan. Broken Nation: Australians and the Great War. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2013.

BEAUMONT Joan. Australia’s War, 1914-18. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1995.

Mythology of the Anzac and the Birth of the Nation

CROTTY MARTIN. “25 April 1915: Australians Troops Land at Gallipoli: Trial, Trauma and the ‘Birth of the Nation.’” In Turning Points in Australian History. Martin Crotty and David Roberts. Eds. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2009.

LAKE, Marilyn, and Henry REYNOLDS. Eds. What’s Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History. Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2010.

STOCKINGS, Craigs. Ed. Zombie Myths of Australian Military History. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010.

STOCKINGS, Craigs. Ed. Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History, Kensington, NSW: New South Pub., 2012.

Australian National Identity

CURRAN, James. The Power of Speech: Australian Prime Ministers Defining the National Image. 2004. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2006.

CURRAN, James, and Stuart WARD. The Unknown Nation: Australia after Empire. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2010.

The Centenary in Australia/Australian Trench Tourism

BROWN, James. Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost of Our National Obsession. Collingwood: Redback, 2014.

FATHI, Romain. “Connecting Spirits: The Commemorative Patterns of an Australian School Group in Northern France.” Journal of Australian Studies, 38:3 (2014): 345-59.

The History Wars

MACINTYRE, Stuart, and Anna CLARK. The History Wars. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2003.

BROWN, Peter. “Mémoire et identité nationale: la ‘guerre des histoires’ en Australie.” Hermès, 52 (3/2008): 133-38.

En français

FATHI, Romain. Représentations muséales du corps combattant de 14-18. L’Australian War Memorial de Canberra à travers le prisme de l’Historial de la Grande Guerre de Péronne: Paris: L’Harmattan, 2013.