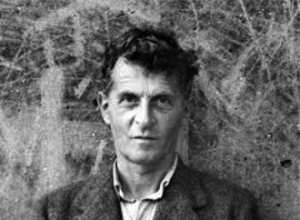

Olivier Berggruen takes an interest in the status of the objects at the home of Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose thought as well as the conditions for his existence he examines. He shows us why it should not be forgotten that Wittgenstein was not only a philosopher but also a gardener, an ambulance driver, and an engineer, as he was, starting in 1926, the partial creator of his sister’s house on Kundmanngasse. His treatment of the slightest details in his architectural work not only has its own significance, but it also sheds new light on his outlook in the domains of art and philosophy. His taste for sparsity does not mean that he failed to pay attention to a variety of objects. Quite the contrary.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Wittgenstein and Aesthetics

Olivier Berggruen

I may find scientific questions interesting, but they never really grip me. Only conceptual and aesthetic questions do that. At bottom I am indifferent to the solution of scientific problems; but not the other sort. [CV, p. 79]

I should like to say: there are aspects which are mainly determined by thoughts and associations, and others which are “purely optical.” [RPPI, p. 970]

Wittgenstein’s Artistic Background

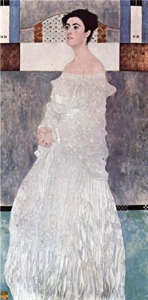

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Margaret “Gretl” Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, oil on canvas, 180 × 90 cm, Neue Pinakothek, Munich

Growing up at a time of unprecedented artistic flowering in fin-de-siècle Vienna, Ludwig Wittgenstein rarely alluded to his privileged background. Though his father Karl was a highly successful tycoon who transformed Austria’s steel industry, the family never shed their outsider status, perhaps owing to their distant Jewish origins. Ludwig and his siblings lived in a grand house on the Alleegasse aptly known as the Palais Wittgenstein. It boasted heavy tapestries, portraits by the fashionable artist Philip de Laszlo, paintings by Giovanni Segantini and Rudolf von Alt, sculptures by Rodin and Max Klinger’s bust of Beethoven. Among other things, Karl Wittgenstein financed the construction of Josef Maria Olbrich’s masterpiece, the Vienna Secession building. Its interior was decorated by Gustav Klimt, who painted a portrait of Karl’s daughter Margarethe (known as Gretl). The family hosted numerous private concerts in the Palais Wittgenstein’s heavily-paneled music room, in the presence of such luminaries as Johannes Brahms and the violinist Joseph Joachim.

It is impossible to overstate the cultural sophistication of the Wittgensteins’ household, their impact at the time stemming mainly from their patronage of the arts. As for Ludwig, his fascination with philosophy prompted him to abandon engineering and to seek the advice of the German logician Gottlob Frege at Jena, before moving to Cambridge to study with Bertrand Russell, the foremost philosopher of his age. Yet, despite his pursuit of philosophy, he never shed his aesthetic and artistic interests.

Music Room, Palais Wittgenstein, no. 16 on the present Argentinierstraße, Vienna, in 1910

The Great War was catastrophic for the Wittgenstein family. Three of Ludwig’s brothers fell and he himself barely survived an Italian prisoner-of-war camp. After that ordeal he rebelled against his background, giving away his inheritance—shortly before his death in 1913, Karl had converted many of his assets into valuable American stocks—and becoming an ascetic in the mold of Count Tolstoy, whose version of the Gospels had sustained Ludwig in the trenches. By then he had ceased practicing philosophy and turned to other occupations, teaching at elementary schools in Lower Austria and working as a gardener. This occurred shortly after the publication of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, the short aphoristic treatise in which he sought to solve most—if not all—of philosophy’s problems.

The Wittgenstein House

Remember the impression one gets from good architecture, that it expresses a thought. It makes one want to respond with a gesture. [CV, p. 22]

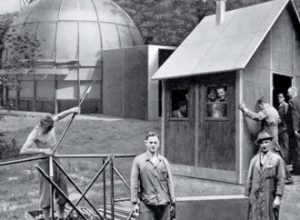

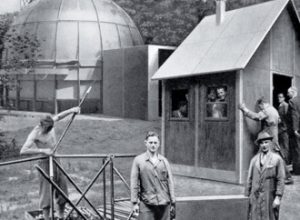

Wittgenstein House by Paul Engelmann and Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1927-1928, Vienna, Kundmanngasse

One of Wittgenstein’s most striking characteristics is the obstinacy and dedication with which he approached his work, be it as an engineer, a gardener, a hospital porter, or a philosopher. A case in point is the house he designed for his sister Gretl, despite his lack of formal architectural training. His standards were rigorously exacting, and he would suffer no deviation from them.

The story of the building is well known. Having failed to find spiritual renewal during his years of self-imposed exile in remote Austrian villages, Wittgenstein welcomed the opportunity to work with the architect Paul Engelmann. Not only was Engelmann a student of Adolf Loos, whose stark modernism Ludwig revered, but the two men were acquainted from their days in the army.

Though Wittgenstein kept close to Engelmann’s original plan, his contribution far exceeds what is generally acknowledged. He refined the layout, altered the proportions of the rooms and designed such architectural details as the windows, doors, handles, and radiators, which he saw as essential to the overall design. He also contributed original, unusual, and costly engineering solutions, such as an invisible pulley system for the window shades. The walls in stucco lustro reflected Wittgenstein’s wish to maintain a similar shine between the house’s flooring and its other surfaces. The latching of the double windows was achieved by means of Espagnolette bolts.

Window Details, Wittgenstein House, by Paul Engelmann and Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1927-1928, Vienna, Kundmanngasse

Wittgenstein’s alterations echoed Loos’s rejection of decorative embellishments. Stories about his eccentricities abound: the year spent designing door handles and radiators, for instance; or the seamless 150-kilogram metal curtain that could be lowered to the floor below. At the last minute, he insisted on raising the living room ceiling by 30 millimeters in order to maintain the original proportions of the house. From various accounts, its severe classicism did not make for a particularly welcoming home, which no doubt explains Gretl’s incongruous but perhaps understandable decision to fill it with comfortable Biedermeier furniture.

Wittgenstein’s work as an architect reflected his other artistic pursuits. In the tradition of Loos, he disdained ornament, preferring more understated forms. In Loos’s famous pamphlet Ornament and Crime, embellishment is deemed superfluous, it having a vexing tendency to go out of style. There was something unhealthy, it argued, about the inflated and degenerate style of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Though Loos never shunned ornament completely, he felt it should conform with a building’s surfaces and materials. Unlike Bauhaus theorists, he refused to subordinate form to function: what mattered was structure. Wittgenstein applied these principles to his own life, whether in his surroundings or in his sober style of dress. As far back as 1912, his rooms in Cambridge had been furnished with simple custom-made pieces commissioned after a series of unsuccessful visits to local furniture shops.

Interior of the Wittgenstein House by Paul Engelmann and Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1927-1928, Vienna, Kundmanngasse

To what extent does the Wittgenstein House reveal its creator’s approach to philosophy or his desire to achieve clarity in the expression of thoughts? (We know that in his lectures Wittgenstein lamented his self-confessed inability to verbalize what he wished to communicate.) What is the relation between Wittgenstein’s life and his aesthetic and philosophical stances?—between his work as an architect and his notion of style? As has often been noted, the Wittgenstein House echoes its designer’s philosophical premises—the stark beauty of the object reflecting the austere, almost paradoxical “logical poetry” of the Tractatus.

After the war, as we have seen, Wittgenstein turned his back on the material excesses of his upbringing. This was driven by a desire for healing and cleansing. Similarly, the Wittgenstein House reflects its author’s desire for simplicity. The building’s austerity harbors a paradox (Wittgenstein’s life was full of them), for despite its somber feel, it is neither menacing nor belligerent. On the contrary, it is fully imbued with harmony, even peace, qualities that Wittgenstein seldom experienced himself. Style is presented as the embodiment of a certain ethical attitude; of the refinement and correction of human endeavor; and of a yearning for serenity in contrast to the nervous strain that ran in the Wittgenstein family, with its upshot of instability and suicide. At the same time, his philosophy, too, took on a distinctly therapeutic edge, an escape from the confusion of thought and metaphysical inclinations.

Michael Drobil, Büste von Ludwig Wittgenstein (Bust of Ludwig Wittgenstein), ca. 1926-1928, white marble, height: 44 cm, private collection

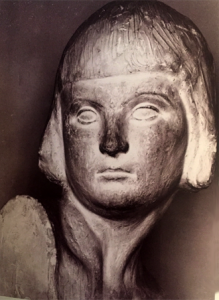

During his time in Vienna (1926-28) Wittgenstein frequented the studio of the sculptor Michael Drobil, who executed a bust of him. In turn Wittgenstein created the plaster likeness of a young woman inspired by his new mentor. By emphasizing the geometrical and the armature of the head, the bust can be seen as a correction and refinement of Drobil’s sculptural style. The face’s features display an austere, serene beauty derived from the tradition of Greek statuary which the philosopher much admired. With the parsing of its structural elements, Wittgenstein’s art follows a path similar to his work as a philosopher. This activity had a distinct therapeutical dimension. There is a parallel here between the desire to liberate us from philosophical confusion and the ensnarement of thought (and do away with metaphysics), and the wish to refine and purify art and architecture of all that is structurally unnecessary.

We can safely assume that Wittgenstein’s work on his sister’s house renewed his interest in the aesthetic. Yet in addition to its therapeutical benefit, what part did aesthetics play in Wittgenstein’s philosophy after his return to Cambridge in 1929?

Aesthetics

Aesthetic attention is directed at a variety of structures—a chair, a funerary cloth, a tiara, a work of art, the falling snow. If the realm of aesthetics is traditionally defined as purely sensory, to what extent can it be investigated objectively? Herein lies a philosophical question (cf. Kant, who defines the aesthetic as disinterested pleasure in the appearance of things) which Wittgenstein addresses in ambiguous ways.

For Wittgenstein the aesthetic realm derives from the customs, traditions, and forms of discourse inscribed within a community of people. The Lectures of 1938, for instance, define aesthetic appreciation as the upshot of a set of temporal and social circumstances. A case in point is his juxtaposition of a Negro mask and King Edward VII’s coronation robe. To appreciate the mask as an African does is to see it within a cultural and historical frame. The same can be said about the coronation robe. “You appreciate [each artwork] in an entirely different way; your attitude to it is entirely different to that of a person living at the time it was designed.” [L&C, p. 10.]

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Mädchenkopf (Head of a Girl), 1927, terra cotta, height: 39.5 cm, private collection

Furthermore, aesthetic pleasure is linked to the awareness of rules or, in a more general sense, a set of skills. The rules are internal to our cultural practices; and their awareness may provide a more refined aesthetic appreciation; this might include technical knowledge, as in the case of an art collector who has learnt to draw or an opera buff who has studied harmony. [See CV, pp. 28-29, 84; Z, p. 164]

. . . if I hadn’t learnt the rules, I wouldn’t be able to make the aesthetic judgement. In learning the rules you get a more and more refined judgement. Learning the rules actually changes your judgement. (Although, if you haven’t learned harmony and haven’t a good ear, you may nevertheless detect disharmony in a sequence of chords.) [L&C, p. 5]

This line of enquiry has had ramifications in France, as embodied by the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. We know that Pierre Bourdieu, who read Wittgenstein extensively, considers judgments of taste to be interested (as in partial). For him, our appreciation of art is inherent to the cultural background from which it is appraised. Comprehension is thus linked to cultural paradigms, that is to say, whether we know it or not, we adhere to our language-games and cultural practices. In the final analysis, Bourdieu’s “socialization of aesthetics” leads to the nonexistence of the aesthetic realm. On this subject, Wittgenstein is more ambiguous: he claims, for instance, that though appreciation may not be linked to the understanding of certain rules, knowledge of the latter may optimize our aesthetic judgment. [See Z, p.164]

Nevertheless, we must avoid conflating the existence or possibility of aesthetic response with that to which it is applied, i.e., the objects we evaluate, which are likely to shift across time and cultures. In other words, these shifts, however real—as between, say, the art of Guido Reni and Rosa Bonheur—do not negate the existence of the aesthetic response.

Wittgenstein’s contextualism must be juxtaposed to his remarks in the Lecture on Ethics and Culture and Value. To see something aesthetically is to see it in the absolute, outside space and time. This is what we call the view sub specie aeternitatis. From this point of view, aesthetic experience involves the realm of the sensory, and the work of art is seen with the whole world as background. Or to put it differently, the work of art, as a telling fragment of reality, can give us a window into the totality of the world. [See N, p. 83]

Furthermore, claims can be made in defense of some kind of aesthetic objectivity beyond time and cultures. In other words, even when a judgment of taste derives from specific localized practices, if the latter are shared by other cultures, the judgment in question can cross the boundary between them. (The same goes for a relativistic view of morality.) It might be worth distinguishing between a view that, while taking aesthetic judgments seriously, links them to specific circumstances, versus a view that is suspicious about the existence of such judgments and regards them as merely part of a cynical play in the game of power, hierarchy, and exclusion. (I owe this point to Paul Boghossian.)

The former allows for the possibility that works may not be culturally indexed, by which I mean that aesthetic appreciation occurs apart and away from community-based contexts. For example, there can be initial traces of taste, of a pure aesthetic awareness, in very young children. A child’s taste may be elementary, yet it indicates a sensitivity to aesthetic types uninfluenced by custom and convention. (By “pure” aesthetic awareness, we mean consistent emotive responses to certain simple forms and combinations of forms, hues, color combinations, sounds, textures, etc., generating commensurate feelings. The sparking of emotive responses by specific stimuli possibly follows rules and is discernible in many children’s early development.)

In later years, Wittgenstein may have become more of a relativist. Still, if we look at, say, the 1938 Lectures, the positioning of cultural artefacts within an anthropological or historical framework does not preclude them from being viewed aesthetically, that is, outside of space and time.

This last point begs another important question, namely aspect-seeing (Aspekt-Wechsel). In Wittgenstein’s lectures, comprehension is likened to grasping a global configuration. A piece of music or a painting is understood in a certain way, like a waltz or a minuet, like a conversation piece or a romantic landscape. At times, he brings up the notion of Aufleuchten, or “lighting-up,” to describe the way in which we recognize a face in a painting. The approach in terms of seeing-as, or aspect-seeing, elucidates how we look at works of art, how we listen to music.

Seeing different aspects in a work of art produces a move away from fixed meaning toward the realm of comprehension and interpretation. What emerges is a notion of the aesthetic not just as a discourse about art, but as a relationship between the beholder and the work. We perceive the latter in one way rather than another. Wittgenstein emphasizes the multiplicity of perspectives in a work of art, yet while all these might exist within a second work too, it is still the first that we want to see. “That means that the chief impression is the visual impression. Yes, it’s the picture which seems to matter most. Associations may vary, attitudes may vary, but change the picture ever so slightly, and you won’t want to look at it any more.” [L&C, p. 36] There is an irreducible aspect to each work, since the feelings and impressions it gives rise to cannot be replicated by another one.

Comprehension

In order to get clear about aesthetic words, you have to describe ways of living. We think we have to talk about aesthetic judgements like “this is beautiful,” but we find that if we have to talk about aesthetic judgements, we don’t find these words at all, but a word used something like a gesture, accompanying a complicated activity. [L&C, p. 11]

The Lectures on Aesthetics (1938) give us a good sense of Wittgenstein’s philosophical methodology. They show a disregard for traditional questions such as how to define a work of art, what is beautiful, how do works express feelings, etc. When there is talk of aesthetic appreciation, Wittgenstein stresses the variety of forms it takes. Understanding is not only conveyed by words, but actions, gestures, etc.

Suppose you meet someone in the street and he tells you that he has lost his greatest friend, in a voice extremely expressive of his emotion. You might say: “It was extraordinarily beautiful, the way he expressed himself.” Supposing you then asked: “What similarity has my admiring this person with my eating vanilla ice and liking it?” To compare them almost seems disgusting. But you connect them by intermediate cases. [L&C, p. 12, §4]

The use of intermediate cases for understanding our aesthetic reactions is related to the concept of family resemblances, which is developed in the Philosophical Investigations. It is a comparative method, rather than the search for essence. What matters is the synoptic view. [See PI, p. 92.] Wittgenstein wants to survey the general terrain of aesthetic pronouncements, to look at the variety of uses to which an expression is put, to reach what he calls a “perspicuous representation.” Such an approach might be termed morphological, in the spirit of Goethe, since morphology is geared toward an overview of the use of particular expressions. Therefore, description is favored over explanation and elucidation reached by overview over hypothesis. Aesthetics should emphasize “certain comparisons, the grouping together of certain cases.” [L&C, p. 29, PI, pp. 24, 291]

Worms and Serpents

Let us conclude via a haunting, enigmatic aphorism from 1931:

A beautiful garment that is transformed (coagulates, as it were) into worms and serpents if its wearer looks smugly at himself in the mirror. [CV, 1931, p. 22]

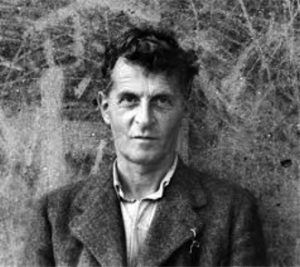

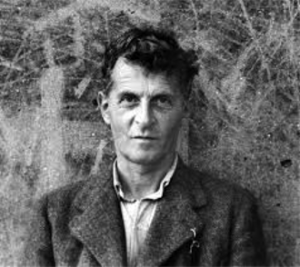

Ludwig Wittgenstein (April 26, 1889—April 29, 1951)

A number of scattered notes testify to Wittgenstein’s emphasis on the notion of style. (For example, he admires La Rochefoucauld’s well-known aphorism, “Le style, c’est l’homme même.”) Style is the outward manifestation of the refinement of the senses that was essential to him. It is organic and deeply felt, never self-conscious to the extent of turning into worms and serpents.

An old style can be translated, as it were, into a newer language; it can, one might say, be performed afresh at a tempo appropriate to our own times. [ . . . ] That is what my building work amounted to. By that I do not mean giving an old style a fresh trim. You don’t take the old forms and fix them up to suit the latest taste. No, you are really speaking the old language, perhaps without realizing it, but you are speaking it in a way that is appropriate to the modern world, without on that account necessarily being in accordance with its taste. [CV, p. 60]

This can be compared to Joshua Reynolds’s Third Discourse (14 December 1770), in which he compares learning the craft of painting to assimilating a language. (There is no evidence of Wittgenstein having read him.)

I cannot help suspecting that in this instance the ancients had an easier task than the moderns. They had, probably, little or nothing to unlearn, as their manners were nearly approaching to this desirable simplicity; while the modern artist, before he can see the truth of things, is obliged to remove a veil, with which the fashion of the times had thought proper to cover her.

In his Discourses, Reynolds was inspired by William Hogarth, who had published two prints in his Analysis of Beauty (1753). Hogarth conceives of a morphology of the perception of natural sights, objects, and artefacts; at the beginning, forms are governed by the serpentine “line of beauty.” Artistic language is modeled on the language of nature. The Analysis of Beauty renders the world readable and gives it an aesthetic dimension. Just like a letter announces a word, the doodles of the child anticipate beauty, not yet structured by the knowledge of rules. Such a vision is hierarchical, with the art of Antiquity at the top. It is therefore the original language of the Ancients that needs to be conquered, once again. As Michael Baxandall’s studies on the Italian Renaissance testify, order and clarity of design were deemed essential. As for style, we might class it as equally significant in that it permeates behavior and has a moral dimension. The fixation on how things are made, what their armature is, the sense of proportions, balance, harmony, and other related concepts all matter to Wittgenstein. The core principles of art and architecture of Antiquity, the noble simplicity of Greek statuary, are the foundation on which art can rest.

The analogy here is that of language and how it relates to style: namely, that while taste and fashion are impermanent, language and style endure. They are the abiding threads that link old and new—not so much the functionalism of the Bauhaus, but the classicism embodied in the Wittgenstein House. It shows that Wittgenstein’s attitude to environment and space, in order to be conducive to peace and satisfaction, is anchored in two related notions: that of space and architecture as conceived by the Ancients, who devised orders, symmetry, and architectural principles based on embodied spatial relations as well as on mathematics; and the fact that these notions are based on universal aesthetic principles that cut across times and cultures. As long as they don’t replicate past forms, objects are not dead things, but engage and readapt these principles to our needs and environment.

I would like to thank Prof. Antonio Damasio, Prof. Paul Boghossian for their comments on an earlier draft of this essay. May Anunciata von Liechtenstein, too, be thanked for her role in the preparation of this talk.

Abbreviations

CV Culture and Value. Ed. Georg Hendrik von Wright in collaboration with Heikki Nyman. Trans. Peter Winch. Oxford: Blackwell, 1998.

L&C Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief. Ed. Cyril Barrett. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1966.

N Notebooks 1914-1916. Ed. G. E. M. Anscombe and G. H. von Wright. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. 2nd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1979.

RPPI Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology. Ed. G. E. M. Anscombe and G. H. von Wright. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell, 1980.

Z Zettel. Ed. G. E. M. Anscombe and G. H. von Wright. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. 2nd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1981.

Further References

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979). Trans. Richard Nice. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984.

BUDD, Malcolm. Aesthetic Essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

LEITNER, Bernhard. The Wittgenstein House. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000.

LOOS, Adolf. Ornament and Crime. Trans. Michael Mitchell. Riverside, CA: Ariadne Press, 1998.

REYNOLDS, Joshua. Discourses on Art. Ed. Robert R. Wark. London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1975.

WIJDEVELD, Paul. Ludwig Wittgenstein Architect. Amsterdam: The Pepin Press, 1993.

WITTGENSTEIN, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. 2nd ed. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958.

_____. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Trans. C. K. Ogden. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1922.

_____. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Trans. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness. New York: Humanities Press, 1961.

Olivier Berggruen (b. 1963, Switzerland), studied in Paris and then studied Art History at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, and then at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. From 2001 à 2007, he was the associate curator at the Schirn Kunsthalle of Frankfurt. Author of The Writing of Art (Pushkin Press, 2011), he is currently preparing a retrospective on Picasso and the Ballets Russes at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome for 2017.