The staging of photographs is a practice that has always existed. As early as the American Civil War, Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan, it is known, certainly moved corpses around in order to render their compositions more “striking,” just as they also reported their models to be “Yankee” or “Confederate” so as to suit the needs of the message they wished to transmit.

Nathan Rera offers us the conclusions of his dissertation, which will soon become a book from Presses du Réel about some much more recent events. He recalls the facts and interprets them. The genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda generated a lot of photographs, starting from the early days of the massacres. Yet those were not the ones that told of the breadth of the catastrophe or of the most widespread ways in which it occurred. The many other ones, taken in accordance with the hurried ways in which the mass media work, were instrumentalized for propaganda purposes. Such photographs served as vehicles for misinterpretations that turned one away from the images.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Nathan RéraRwanda:

Images of the Disaster From the Time of News Coverage to the Time of Memory

Between April and July 1994, the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda left more than 800,000 victims in its wake. For some, this involved a confused media narrative; for others, a paradigm of human barbarity. The event generated a wealth of visual representations, mainly in the fields of photography and cinema. In many respects, the questions post-Rwandan genocide works raise find strong echos in the debates over the representation of the destruction of the European Jews—an event that has been described, following Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 film Shoah, as “unrepresentable.” The genocide of the Tutsi nonetheless demands recognition for its uniqueness, in that it was a media event: an event with deceptive contours, to be sure, one that was politically instrumentalized and that brought about a deep moral crisis—the same “unhappy consciousness” of which Michel Poivert speaks apropos of Gilles Caron. [1] Photographers and cameramen arrived in the Rwandan capital rather soon after the start of the massacres, and while they were not as numerous as were their colleagues in Bosnia during the same period—a few dozen, at most—the major news agencies were represented. Four to five days after the genocide began, the first images of the Rwandan disaster appeared in the press and on television.

From Discrimination to Genocide

Not very well known at all by most of the media in 1994, Rwanda, a small, landlocked country at the heart of the African Great Lakes region, has long held to the imagery forged by the first colonists: that of the “country at the source of the Nile,” dominated by a “race of Lords” (the Tutsi giants), a shepherd people who had come from Abyssinia to subjugate the “race of serfs” (the Hutu), caricatured as exploitable “niggers.” Supported and instrumentalized by the White Fathers and the Belgian administration (which introduced, in the early 1930s, an “ethnicity” category on identity cards), the Tutsi monarchy faltered when the Hutu contested its power. After the proclamation of Independence in 1962, armed movements of Tutsi exiles attempted several incursions into the country, while discrimination and violence against the Tutsis still living inside the country intensified. The arrival of the Hutu general Juvénal Habyarimana as head of State following a putsch orchestrated in July 1973 in no way improved the fate of Tutsis domestically: a system of ethnic quotas even served to marginalize their place within Rwandan society. The outbreak of civil war between the Government’s Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (FPR), made up of Tutsi from the diaspora, forced Habyarimana to sign the Arusha Accords, which, as it provided, in particular, for the holding of multipartite elections, incurred the wrath of the advocates of “Hutu Power.” [2] On April 6, 1994, the Rwandan President died while returning from a regional summit in Tanzania, his Falcon 50 airplane blown up by a missile as it was preparing to land. [3] The assassination of opponents of the regime and then of the Tutsi began in the capital, under the leadership of the military and of the Hutu militia.

Images of Horror: Between Rememoration and Occultation

Western journalists came on the scene during the first days of the massacres, basically in order to cover the evacuations of expatriates as part of a joint Franco-Belgian operation. [4] Unable to go near the roadblocks where the killings were taking place, most of the photographers and cameramen followed the trail behind the parachutist-commando squads. A few images that give a (brief) glimpse of the violent acts being committed nonetheless came to light, though without assuring a clear view of how the situation was evolving in the Rwandan capital. Thus, the sequence filmed with a telephoto lens by Nick Hughes from the roof of the Saint-Exupéry School, where a genocidal man is seen striking his victim with a club or a machete, was broadcast (and rebroadcast) by French television networks as early as April 11, 1994, as testimony to the barbarity.

1. Patrick Robert, Nyanza Hill, April 21-23, 1994. Mass grave of ca. one hundred victims murdered by the army and the Hutu militia. ©Patrick Robert, Sygma/Corbis, all rights reserved.

At the end of the evacuation operations, the majority of journalists left Rwanda along with the military, with the exception of two photographers, Patrick Robert (Sygma) and Luc Delahaye (Sipa).[5] Having succeeded in embedding himself in an FPR squadron, they discovered, between April 21 and 23, a mass grave of around one hundred Tutsi corpses on the hill around Nyanza [illus. 1]. Their images, the first to give a visual account of the breadth of the massacres, were not widely disseminated in the media.[6] The second half of April thus constituted a veritable “black hole” in media coverage, which was partially filled in early May 1994 when photo and video reporters, profiting from the fact that some territories in eastern Rwanda had fallen into the hands of the FPR, were able once again to enter the country in order to document the traces of genocide.

Media Cliches and Confusions

Thus, in the month of May numerous images succeeded in arriving in the West. Many showed the remains of Tutsis abandoned in schools and churches or tossed about by the current of the Akagera River. Nonetheless, what predominated, across the media, were the spectacular scenes of the exodus of Hutu civilians. The photographs of the refugee camps in Tanzania, like those by Sebastião Salgado, bore witness to an apocalyptic spectacle and lent themselves to various confusions: those tens of thousands of displaced persons, distraught and emaciated shadows of their former selves, looked like “survivors of the genocide.” In reality, though, they were fleeing the advance of FPR troops and the persistent rumors of reprisals. The French army, which had previously gained renown in Rwanda for its support and training of the Hutu military, belatedly arrived on the scene on June 22, 1994. Under cover of setting up a “humanitarian safe zone” in the southern part of the country, the main objective of this new operation, named “Turquoise,” was to polish up the tainted image of Mitterrand’s France, which had been accused of supporting the extremists responsible for the massacres.

After the FPR’s victory in early July, Hutu civilians, fearing reprisals from the victors, headed en masse toward Zaire. In the refugee camps, where the authors of the genocide also were to be found, a cholera epidemic broke out that was taken by the media to be the “sequel to the genocide in Rwanda.” Consequently, the predominant iconography of the genocide was drawn up on the basis of a major misinterpretation, heightened by the presence of French Army bulldozers carting away cholera corpses to pits dug for their burial. Covering over the event with a dubious veneer, the specter of the Holocaust was summoned up through the use of images from the liberation of Bergen-Belsen in 1945. In Clément Chéroux’s analysis, those images have gained notoriety on account of their symbolic dimension and to the detriment of their documentary value.[7].

Crises of Representation

2. Alfredo Jaar, Real Pictures. Installation presented at the Rencontres Photographiques d’Arles 2013, Église des Frères-Prêcheurs. ©Baptiste Astier, all rights reserved.

In the aftermath of the genocide in Rwanda, Western artists were quick to react. Such reactions were initially a way of denouncing the media’s wait-and-see attitude. The “Rwanda Project” of the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar, fitted out with twenty-five different installations, is emblematic of this desire to shed light on the event by pointing an accusing finger at the editorial offices of the Western media, which were said to have failed in their historic task. In Real Pictures (1995) [illus. 2], the photographs taken by Jaar in Rwanda following the genocide are not visible but rather hidden away in black boxes—“image cemeteries”—where only inscriptions on the covers allow visitors to forge a mental image of them. Setting words against images, Jaar thus intended to turn upside down the logic of the media as the generator of “shock-photos” and “decisive moments,” opting instead for a sometimes simplistic rhetoric of unrepresentability.

This crisis of images is palpable, in quite another way, in the works of some photographers and cameramen who have passed from journalism to art. Several of them broke ranks with the media machine, preferring to construct a personal oeuvre set against the temporality inherent in news gathering. Gilles Peress was one of the first to challenge the media discourse. Present in Rwanda in 1994 as a Magnum photographer, he had already been working on images in a unique way no longer beholden to the two-page magazine spread. In 1995, he published The Silence,[8] the point of departure for a vast work in progress that has been exhibited at the greatest international museums (the Pompidou Center, the Picasso Museum in Paris, New York’s MoMA, etc.). The irruption of images of horror in the sanctuary of art nevertheless reopened debates about the “aestheticization of reporting” and the blurring of the boundaries between photojournalism and art photography.[9]

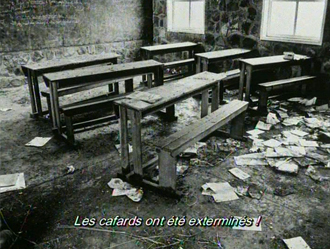

3. Still image from Itsembatsemba: Rwanda One Genocide Later by Alexis Cordesse and Eyal Sivan.

Moreover, the process of memorialization begun in Rwanda after the genocide itself engendered new images. Murambi, an unfinished school where nearly 40,000 Tutsi perished, became one of the emblematic places for remembering the genocide, particularly on account of the exhibition, for testimonial purposes, of some 800 corpses covered in lime. Shown over again and again in photographs and films, these staggering images present, however, only the visible part of Rwandan history by introducing us “to the scandal of the horror, not to horror itself.”[10] After having photographed the Murambi corpses “while holding his breath,” Christophe Calais began a series of blurry images on the roads of Rwanda,[11] a way of approaching a more subterranean memory of the event. In a different way, Alexis Cordesse directed a short film, Itsembatsemba: Rwanda One Genocide Later (1996)[12] [illus. 3], which pertinently questions the flaws in the image. This film, made for the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the organization Doctors Without Borders, links a series of black-and-white photographs, sounds recorded as the images were shot, and snatches from the audio archives of Radio-Télévision Libre des Milles Collines, which constitute obviously incriminating evidence against the authors of the genocide.[13] The objective of this photographer’s approach, which is situated beyond the contingencies of media reporting, is to fathom, as with a seismograph, the “invisible movements that survive”[14] on faces and landscapes, thereby offering a postmortem examination of fragments of the genocide in the mode of a poetics of mortal remains.

Notes

[1] Michel Poivert, Gilles Caron. Le conflit intérieur (Lausanne/Arles: Musée de l’Élysée/Photosynthèses, 2013).

[2] The goal of this extremist ideology was to destabilize the democratization process favored by Hutu moderates by instrumentalizing hatred of the Tutsi via the use of some media outlets (such as the newspaper Kangura).

[3] The investigation into who committed this assassination, which has regularly supplied the news with fresh polemics, is still ongoing. The credibility of the conclusions of Judge Bruguière, who accused FPR officials, was undermined by the existence of false testimony. The latest advances in the case, since Marc Trévidic took over, leaves one with the impression that the assassination was perpetrated by Hutu extremists.

[4] Amaryllis and Silver Back, April 8-14, 1994.

[5] In June of the same year, Delahaye quit Sipa to join Magnum Photos.

[6] Patrick Robert’s photographs were belatedly published in Newsweek and Stern (the series can be viewed on the photographer’s website: www.patrick-robert.com). Luc Delahaye, who had filmed the Nyanza mass grave with a camera entrusted to him by Reuters, was able to send his images to the France 3 television network, which broadcast less than two minutes of his footage on April 25, 1994.

[7] See Clément Chéroux (ed.), Mémoire des camps. Photographies des camps de concentration et d’extermination nazis (1933-1999) (Paris: Marval, 2001).

[8] Gilles Peress, The Silence (New York: Scalo, 1995).

[9] See, for example, the critique by Agnès Sinaï, “L’art contemporain face à l’histoire. Chronique d’une amnésie postmoderne,” Esprit, 230-231 (March-April 1997): 71-82.

[10] Roland Barthes, Mythologies [1957] (Paris: Éditions Points, 1970), p. 117. The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), p. 73.

[11] See the photographer’s website:

http://www.christophecalais.com/diaporama.php?nrep_id=166

[12] Available on the photographer’s website at:

http://www.alexiscordesse.com/video_1_2_1_0_Itsembatsemba ; with English subtitles, at: http://vimeo.com/60896268.

[13] RTLM began broadcasting in July 1993. As the genocide was taking place, calls for ethnic cleansing were made daily.

[14] Georges Didi-Huberman, L’Image survivante. Histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 2002), p. 123.

Selected Bibliography

“Les politiques de la haine. Rwanda, Burundi 1994-1995.” Les Temps Modernes, 583 (July-August 1995). 315pp.

“Rwanda, quinze ans après. Penser et écrire l’histoire du génocide des Tutsi.” Revue d’histoire de la Shoah, 190 (January-June 2009). 512pp.

Jean-Pierre CHRÉTIEN, Jean-François DUPAQUIER, Marcel KABANDA et Joseph NGARAMBE. Rwanda, les médias du génocide. Paris: Éditions Karthala, 1995. 397pp.

COQUIO, Catherine. Rwanda: le réel et les récits. Paris: Éditions Belin, 2004. 217pp.

Didier EPELBAUM. Pas un mot, pas une ligne? 1944-1994: Des camps de la mort au génocide rwandais. Paris: Éditions Stock, 2005. 355pp.

Pierre HALEN and Jacques WALTER. Eds. Les Langages de la mémoire. Littérature, médias et génocide au Rwanda. Metz: Université Paul Verlaine, Centre de recherches Écritures, 2007. 403pp.

Edgar ROSKIS. “Génocide sans images. Blancs filment Noirs.” Le Monde Diplomatique, November 1994: 32.

Allan THOMPSON. Ed. The Media and the Rwanda Genocide. London: Pluto Press, 2007. 463pp.

Nathan Réra who has a doctorate in Contemporary Art History, is a postdoctoral fellow at Labex Créations, arts, patrimoine (University of Paris-I/HiCSA). His research bears on the relationships among the arts and on the visual representations of genocides. The theme of his dissertation, written under the direction of Pierre Wat and Sylvie Lindeperg, dealt with photographic and cinematic media representations of the genocide of the Tutsi (forthcoming from Presses du Réel, 2014). He is the author of two works for Éditions Rouge Profond: De Paris à Drancy ou les possibilités de l’art après Auschwitz (2009) and Au jardin des délices. Entretiens avec Paul Verhoeven (2010).