There was a time when war was so loved and considered so normal that history itself was thought to be made up especially of military battles, conquests, and heroism. That was the way it was in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, when the Dutch were victorious over the Spanish occupiers in 1648. Within a Reformation atmosphere, one witnessed the emergence of a new artistic vein that took for its subject soldiers at rest, playing, drinking, eating, smoking, and sleeping while waiting to be called up to fight on the battlefield. In the “vanguard,” young painters not only bore arms but also carried forth a novel conception of art while working on a new history. Léonard Pouy, who is currently preparing a dissertation on the emergence of the guardroom scene in seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting, delivers to us here his initial conclusions.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of October 3rd, 2012

Léonard PouyPainters at War:

The Emergence of the Guardroom Scene

in Seventeenth-Century Holland

It is advisable, when studying a given society, to take an interest in the very conception that society has of its own history. Now, for a mid-seventeenth-century Dutchman, as well as for most Europeans of the time, the most tangible part of his country’s history is above all the military part, made up as it was of a thousand years of battles and conquests, most of them victorious. Obviously palpable in space, the Netherlands’ victory over the Spanish occupying forces in 1648 was equally palpable in time. It colored in that age the reading of an entire national history starting from the prophetic revolt of the Batavian Gaius Julius Civilis, who took advantage of the death of Nero to drive out the Roman occupying forces in 69 C.E.—that is to say, exactly 1,500 years before the beginnings of the Eighty Years’ War. Thus, for the “war atheists” we are today, it is not an exaggeration to speak of militaristic culture within a society in which war, considered as the State’s primary role, was (to borrow Martin Luther’s terms) “as needful and useful to the world as eating and drinking or any other work.”[ref]Martin Luther, “That Soldiers, Too, Can Be Saved,” Works of Martin Luther, trans. with Introductions and Notes, vol. V (Philadelphia: A. J. Holman Company and The Castle Press, 1931), p. 36.[/ref]

In a climate of overall reformation that, from politics to religion and passing by way of art, touched the whole of Dutch society at the time, a certain number of new compositions emerged around a single set of military themes painted by young artists in search of recognition. Usually taking as their subject relaxing soldiers who had taken refuge in dark interiors and who were busy drinking, smoking, sleeping, and gambling while awaiting call-up, these compositions were quickly given the label cortegaerd (from the old French corps de garde) by various art experts and art theorists. Inherited from various rooverijen, or scenes of robbery, and other boerenverdriet, or peasant woes, the first guardroom scenes offered a clearly negative image of soldiers. Likewise, while at the dawn of the seventeenth century, in his lives of artists, Karel van Mander presented the god Mars as the possible father of Harmony in association with Venus, he linked Mars especially to the ravages of war that had recently affected numerous artists.[ref]Karel van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck (Haarlem, 1603-1604), fol. 274r20, fol. 260v19, fol. 261v30, fol. 299r14, and v31.[/ref] His Schilder-Boeck (Painter book) nonetheless lacked one biography needed to explain the reasons for such a historiographical trauma: that of van Mander himself. Having settled in Haarlem in 1583, the painter-art theorist had in fact just left his hometown, Meulebeke, in western Flanders, where an encounter with some marauding soldiers had nearly cost him his life.

Initiated, in some cases, into the art of war in their youth, artists such as Pieter Codde (1599-1678), Willem Cornelisz. Duyster (1599-1635), and Daniël Cletcher (ca. 1599-1632) frequented the world of the barracks even when they were themselves not part of it. Referring at the start to this burning issue of the military described by Van Mander, their compositions nevertheless quickly moved away therefrom and thereby brought about a thoroughgoing transformation, as subtle as it was radical, in the iconography of the pillaging mercenary.

From Pillager to Art Lover

1. Willem Cornelisz. Duyster, Soldiers Fighting over Booty in a Barn, ca. 1623-1624. Oil on panel, 37.6 x 57 cm. National Gallery, London, Inv. NG1386. ©National Gallery, London.

Enriched with some complex attributes and represented in accordance with the new norms being set down by the most recent handbooks in military theory, the Dutch soldier gradually left behind the sad rags of the pillaging mercenary so as to don the luxurious attire of the enlightened and refined officer capable of showing leniency toward his prisoners and exhibiting a certain amount of taste, nay expertise, with regard to pillaged objects.

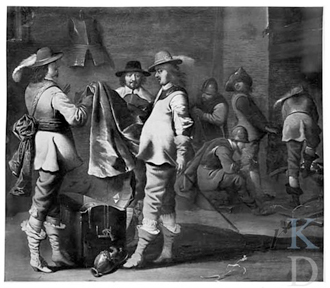

2. Pieter Jansz. Quast, Guardroom with officers examining the catch of a looting, with men around a fire in the background. Oil on panel, 46 x 52.5 cm. Sold in Vienna at Dorotheum’s, April 13, 1943, lot 109. ©Rkd.nl

As early as the mid-1620s, in his Soldiers Fighting over Booty in a Barn (now in London; see illustration 1), Duyster emphasized the value of the materials the violence to which they had given rise represented, even when no soldier showed any direct interest in them. A few years later, Pieter Quast broke up this dichotomy by placing the soldier back within a discussion over the evaluation of the pillaged good (illustration 2). At the same time that the officer ennobled himself by taking on the new role of expert, the artist displayed his talent by representing various textures and materials. Stimulating the eye of the viewer in this way, the painter fulfilled the desires of such art theorists as Philips Angel, who was then campaigning for more naturalism in painting. Other artists, like Simon Kick, offered representations of similar scenes. In a guardroom scene now at the Kunstmuseum Basel (illustration 3), Duyster, however, went further: two elegant soldiers examine the contents of a chest a sumptuously dressed young woman, seated at their feet, has just opened for them. This lady is attempting to draw the attention of the two men to a pearl necklace. Among the various pieces of silverware and other luxurious materials already brought out from the chest, a single object nonetheless captures their interest: a small painting.

3. Willem Cornelisz. Duyster, Soldiers in a guardroom, with a woman showing them precious objects. Oil on panel, 49 x 40.5 cm. Kunstmuseum, Basel, Inv. 1340. ©Kunstmuseum Basel

In line with how the rhetoric of war and the arts evolved in theoretical treatises, this same ambiguity is also to be found in texts written at the time. Whereas Van Mander saw in the barrack-room “the crude children of Mars, the enemy of art,” the painter and art theorist Philips Angel (1618-ca. 1665) tells us a quite different story in In Praise of the Art of Painting, a transcript of his speech given in Leiden in 1641 to a gathering of painters brought together to obtain their guild dues. Drawing from Vasari an episode in the life of Parmigianino (1503-1540), Angel reports how, right in the middle of the Sack of Rome, Charles V’s Landsknechte, who had come to rob the artist’s studio, were changed into subdued gentlemen at the sight of his works [ref]Philips Angel, Lof der Schilder-Konst (Leiden, 1642), p. 15. Michael Hoyle’s translation, Praise of Painting, appears in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 24:2/3 (1996): 227-58; see page 36.[/ref].

Under the Aegis of Minerva, Between schild and schilder

Mirroring this gradual likening of the figure of the officer to that of the art lover, one finds the likening of the painter to the officer, reigning over his knechten or assistants. Presented in embryonic form in Duyster’s work in the early 1630s, this iconography, which merges the spaces of the guardroom and the studio, is to be found again during the following decade, as developed in Flanders in the work of David Teniers the Younger and his followers. Those followers substantially revived the genre at a time when certain Dutch artists, such as Jacob Duck and Anthonie Palamedesz., were displaying a certain amount of repetition in their works.

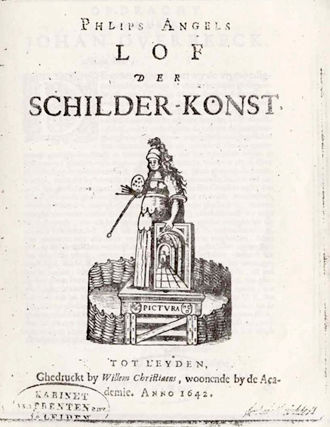

4. Philips Angel, Lof der Schilder-Konst (Leiden: Willem Christiaens, 1642). © Prentenkabinet Universiteit Leiden

While fitting into a noble history of art, Angel also participates in this merger between painters, soldiers, and art lovers. Sprinkling his text with metaphors and expressions that issue from the art of war,[ref]Op. cit., p. 40; see p. 244 of the English translation.[/ref] Angel, too, undergoes a militarization of his status as an art theorist, like the guardroom painters he mentions several times, [ref]Op. cit., pp. 42-43; see pp. 244-45 of the English translation.[/ref] and he goes so far as to place a figure of Minerva as the frontispiece to his work (illustration 4).[ref]See, on this topic, H. Perry Chapman, “A .Hollandse Pictura: Observations on the Title Page of Philips Angel’s ‘Lof der schilder-konst,’” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, 16 (1986): 233-48.[/ref] Represented here with her helmet on, a palette and brushes in her hand, the goddess has now replaced Luke as the patron saint of painters. The connections Minerva maintained with the art of painting were indeed palpable at the time, through analogy between the term schild, or shield, and that of schilder, or painter. Goddess of wisdom and war, what she embodied above all was this new image of a theoretical and scholarly form of art. While wishing for artists to take their inspiration from nature rather than from preexisting works, Angel nevertheless draws this figure from another title page, one composed by Isaeck van Aelst for Samuel Marolois’s (1572-1627) book on Perspective, which appeared in Amsterdam in 1638 and which itself borrowed from the treatises of Hans Vredeman de Vries. A mathematician, too, Marolois was at the time a key figure in the exchanges taking place between the artistic and military theories of the era. In addition to his much-talked-about treatise on perspective, he was principally the author of a number of works on military architecture.[ref]Let us mention here his book on fortifications, published at the Hague in 1615; The Art of Fortification, or Architecture Militaire as Vvell Offensiue as Defensiue, Compiled & Set Forth, by Samuell Marolois Revievved, Augmented and Corrected by Albert Girard Mathematician: & Translated out of French into English by Henry Hexam (printed at Amsterdam for M. Iohn Iohnson, Anno 1631).[/ref]

After the end of the war in 1648, theoretical expositions of the guardroom scene quickly lost their intensity and their “commitment,” and this occurred in a direct proportion to their gradual acceptance. Right before his death, Duyster, who had nevertheless been one of the pioneers of the genre, dissolved the various attributes and references of that genre so as to execute purely atmospheric pieces. Other artists, like Palamedesz., Duck, Maerten Stoop, and Gerard Ter Borch, oriented their compositions toward greater gallantry, sometimes combining the guardroom theme with that of merry company. The figure of the officer then alternated between that of the gallant military noble and the likeable, fat, red-faced troop leader enjoying the company of a family that follows him around in his deployments. These artists could then supply a market on a regular basis without having to suffer too greatly the effects of changes in fashion—beyond, of course, the need to update people’s tastes in clothing, which were increasingly being influenced by France.

Dating back to the 1630s, this twofold cross mutation of the artist into a soldier testifies to the deployment of an intense movement of artistic legitimation begun by an emerging class of painters who were eager to establish their independence from a dominant form of painting and who were the bearers of a new theoretical discourse.

If a war of art really did take place in Holland during the first half of the seventeenth century, it was therefore a war of conquest of markets and statuses conducted by young artists who saw themselves as members of a modern painting corps, the founders of an aristocracy that had newly come into existence since the Netherlands Revolt. These artists went so far as to identify with their subjects, or even those of the Revolt itself. More than the representation of a historical truth, what above all the guardroom scene thus proclaims, through its complexity and its richness, is the autonomous empowerment of a visual language in relation to a history to which it belonged while at the same time constructing it.

Selected Bibliography

BORGER, Ellen. De Hollandse kortegaard: Geschilderde wachtlokalen uit de Gouden Eeuw (exhibition catalogue). Zwolle: Naarden, 1996. 80 pp.

KUNZLE, David. From Criminal to Courtier: The Soldier in Netherlandish Art, 1550-1672. Leiden/Boston/Köln: Brill, 2002. 662 pp.

VAN MAARSEVEEN, Michel P., HILKHUIJSEN, Jos W. L. and DANE, Jacques. Eds. Beelden van een Strijd: Oorlog en kunst voor de Vrede van Munster 1621-1648 (exhibition catalogue). Delft: Stedelijk Museum Het Prinsenhof and Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers, 1998. 384 pp.

ROSEN, Jochai. Soldiers at Leisure: The Guardroom Scene in Dutch Genre Painting of the Golden Age. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010. 220 pp.

SALOMON, Nanette. Jacob Duck and the Gentrification of Dutch Genre Painting. Doornspijk: Davaco, 1998. 192 pp.

Léonard Pouy is currently preparing a dissertation, directed by Professors Alain Mérot (University of Paris-Sorbonne) and Jan Blanc (University of Geneva), on the emergence of the guardroom scene in seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting. A research fellow at the French National Institute of Art History since October 2010, he is also a collaborator in the “Tableau Vivant: Iconographic and Textual Sources” research program directed by Julie Ramos (University of Paris-I).