Between 1830 and 1870, at the time of the French colonial conquest of Algeria, more and more representations appeared. Yet, with few exceptions, these representations camouflaged the sufferings on both sides, and hardly anyone but Tony Johannot directly evoked the brutality of colonization. Johannot fixed in place the image of the “smoke out” from the Dahra caves, where the location population was suffocated using a technique advocated by General Thomas Robert Bugeaud, whereas an artist like Horace Vernet, who was enlisted to paint heroic conquests, was not fooled about the violence he had witnessed.

Nicolas Schaub offers us an excerpt from his research, which will be presented in a forthcoming book that draws on his dissertation: L’armée d’Afrique et la représentation de l’Algérie sous la monarchie de Juillet (The Army of Africa and the representation of Algeria under the July Monarchy).

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Nicolas SchaubThe Conquest of Algeria

Through Images

Between 1830 and 1870, nothing could allay or stop the war of extermination conducted on both sides in Algeria. The sudden appearance of Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud’s soldiers has long surrounded the representation of colonial conquest. One hundred years after the first battles, these monsters were still recognized. As Mouloud Feraoun recalled to Albert Camus:

When a woman from the jabal (mountains) or the interior wanted to frighten her child in order to silence him, she said, “Be quiet, here comes Bouchou.” That was Bugeaud. And Bugeaud, that was a century ago! That’s where we still were at, in 1938.[ref]Hédi Abdel-Jaouad, Rimbaud et l’Algérie (Paris: Paris-Méditerranée, 2004), p. 149n.1.[/ref].

1. Benjamin Roubaud (1811-1847), Le retour d’une razzia (Return from a raid), lithograph, 22.3 x 29.3 cm. From Aubert Éditeur, excerpted from the series “Nos troupiers d’Afrique” (Our soldiers from Africa), 1844-45, which appeared in Le Charivari, December 1844. Private collection. The caption reads: “Dis donc Chauvin… c’est cocasse les hasards de la guerre, nous étions hier dans l’infanterie et nous v’là aujourd’hui dans la cavalerie… ça ne fait rien, c’est tout d’même flatteur de revenir comme ça à cheval sur les produits de ses conquêtes… et v’là des bourriquets dont nous tirerions un crâne parti s’il [sic] pouvaient nous conduire seulement à Montmartre!” (So, Jingo . . . funny how in war, yesterday we were in the infantry and today here we are in the cavalry. . . . No big deal; it’s even flattering to come back like this mounted on the proceeds of our conquest . . . and here we have the little donkeys; we could take gallant advantage of them if only it [sic] could lead us to Montmartre!)

Peasants enlisted for seven years of military service constituted the main mass of the Army of Africa. They discovered very quickly the frightening side of Algeria, where they were plunged into an infertile world often permeated with delirious illusions.[ref]During the Algerian War, it was also peasants who were sent into battles.[/ref]. In 1841, an observer as lucid as Alexis de Tocqueville noted the inability of these men to adapt to such an unbearable reality. “Coming straight from their villages, their undisciplined imaginations are struck by the foreign and terrible nature of this war, and they become prey to nostalgia and to illnesses that the climate threatens to inflict. They are the ones, in general, who succumb to delirium during the long summer marches and kill themselves for fear of not keeping up with the columns.”[ref]Alexis de Tocqueville, “Essay on Algeria,” in Writings on Empire and Slavery, ed. and trans. Jennifer Pitts (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), p. 79.[/ref] At the time, people never could grasp this suffering on the part of the military and as a result they allowed themselves to be blinded all the more by the legend and the colonial epic.

The Violence of War

In the 1840s, Marshal Bugeaud’s methods of continuous warfare were one of the principal reasons for the violent insurrections that destabilized the colony. Each time these revolts broke out and suddenly spread, the authorities failed to understand the gravity of the danger at hand. Abdelkader El Djezairi dealt in this way the blows that challenged “the future” of the occupation.[ref]On the iconography of the representations of Abdelkader, see the works of François Pouillon.[/ref] This resistance to the invader was fed by “the hatred of the stranger and the infidel who has come to invade their country”[ref]Tocqueville, “Essay,” p. 64.[/ref] —a dynamic that escaped the July Monarchy’s military men and politicians. Only Tocqueville understood, and no doubt rather early on, the effects of this radical confrontation: “In a word, it is clear to me that whatever happens, Africa has henceforth entered into the movement of the civilized world and will never leave it.”[ref]Ibid., p. 61.[/ref] Resistance and repression are two mechanisms of power that operated on this territory and that affected the artists who were to voyage there.

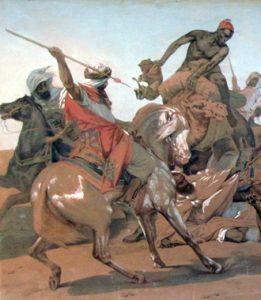

Spurred on by the young officer Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière, “the most inhuman of all the great chiefs of Africa,”[ref]Charles-André Julien, Histoire de l’Algérie contemporaine. La conquête et les débuts de la colonisation (1827-1871) (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1964), p. 316.[/ref] the principle of systematic devastation was established ca. 1840. Employing the ruthless technique of raiding [razzias], Lamoricière applied an effective doctrine of war stoked by war. The history of the agonies and tortures caused by these raids appears only in the correspondence of officers, and it is literary images, often from personal archives, that predominate. They are lively material reported by the actors in the drama being played out. Such letters, addressed to parents and friends, express ambiguous emotions that do not, however, prevent the authors from taking an acute look at the deeds and the men of the African campaigns. In reading these texts written by Pierre François Joseph Bosquet, Lucien-François de Montagnac, and Jacques Leroy de Saint Arnaud, one understands how a war imaginary was constructed on the basis of the experiences of pillaging. This generation of officers assimilated and reconstructed a Romantic aesthetic that was transformed and subverted to express a case of systematic destruction.

It was during this period that the noun razzia and then the verb razzier entered into the French language. Narratives and images brought to light these violent practices that became picturesque in the eyes of Western spectators. Collectors and art lovers acquired aesthetic objects that came from African razzias and, little by little, such objects filled up their bourgeois homes. After each operation, military leaders as autonomous as Lamoricière or Giuseppe Ventini (“Yusuf”) distributed to their soldiers horses and mules, carpets, jewelry, silver, etc. Most often, the needs of the troops and not any military interest were that determined these pack movements. Everywhere, the countryside was burned, enemies were massacred, and women were raped. Most often, the officers gloried in these practices and did not seek to reestablish discipline. In time, the procedures for punishment became more elaborate. In Kabylia and at oases, the army set fire to ksours (fortresses) and villages, and what they did above all was cut down fig trees and palm trees, causing irreparable ruin.

2. Tony Johannot (1803-1852), Les grottes du Dahra (The caves of Dahra), 1845, 27 x 19 cm, etching excerpted from a work by Pierre Christian (1811-1872), L’Afrique française, l’empire de Maroc et les déserts de Sahara . . . (Paris: A. Barbier, [1846]). Private collection.

Scandal broke out in 1845, with the affair of Colonel Aimable Pélissier’s smoking out of insurgents from the caves of Dahra, Pélissier having refused to let these insurgents live, despite their promises to surrender and pay a ransom. The crime this officer committed there was not some isolated incident, as it was preceded and followed by other fires and massacres in the course of the conquest. However, he wrote a report describing in precise terms the sufferings of his victims, this document reaching all the way up to the French Minister of War. Politicians and journalists then seized on this news in order to denounce the excesses of the army, and public opinion was touched by the tragedy. The lithographer and engraver Tony Johannot formulated a romantic and somber view of this group execution. The authorities, however, systematically covered up such abuses and engaged in various forms of censorship that gave officers a totally free hand. Instances of collusion were numerous. Moreover, the powers-that-be orchestrated a genuine propaganda campaign through the use of images that served to legitimate the violence of colonial warfare.

Propaganda by Images

3. Horace Vernet (1789-1863), Scène d’Arabes dans leur camp, écoutant une histoire (Scene of Arabs in their camp, listening to a story), 55.8 x 80.5 cm, lead pencil and watercolor with white gouache highlights on bistre-colored paper, Prints and Drawings Office, Strasbourg Museum of Fine Arts, inventory no. 77.986.0.138.

For fifteen years, the Army of Africa had huge means at its disposal to defeat Abdelkader and his resistance fighters. What was also required was the established power’s orchestrated celebration of national glory and colonial epic struggle. Horace Vernet (1789-1863) was specially enlisted to paint the monumental battles for the Palace of Versailles.[ref]See Michael Marrinan, “Schauer der Eroberung. Strukturen des Zuschauens und der Simulation in den Nordafrika-Galerien von Versailles,” in Stephan Germer and Michael F. Zimmermann, eds., Bilder der Macht/Macht der Bilder. Zeitgeschichte in Darstellung des 19. Jahrhunderts (Munich: Klinkhardt and Berlin: Biermann, 1997), pp. 267-96.[/ref] His bearing and his behavior predisposed him to invent the visual means for understanding this new modern-military world. To a large extent, his numerous compositions molded this war of conquest by imposing a reading of the events and establishing their legendary character for a long time to come.

As early as the late 1830s, Vernet strove to paint but the glorious aspects of the Algerian conquest. The reality of massacres no doubt appeared to him to be an impossible pictorial motif, as it could call back into question not only the prestige of the Army of Africa but also the very meaning of this conquest. These catastrophes from the past had to sink into oblivion so as not to hinder civilization’s march of progress. In the name of colonization, the artist chose not design a single work in support of such abject acts as smoking people out. He undoubtedly recollected his past experiences with violence in Algeria, and similar views directly affected his work.

4. Horace Vernet (1789-1863), Chasse au sanglier (Wild boar hunt), 55.8 x 80.5 cm, lead pencil and watercolor with white gouache highlights on bistre-colored paper, Prints and Drawings Office, Strasbourg Museum of Fine Arts, inventory no. 77.986.0.140.

As with others involved in the conquest and its popularization, Vernet evinces a problematic discrepancy between the complexity of his reactions in the field and the unvarying frames for propaganda ultimately erected into collective representations. To evoke nothing of the most grievous consequences of the military occupation is obviously a sign of the artist’s great discomfort. Vernet drew up no image of these crushed people, for he knew too well its power of propaganda over the public at that time. Moreover, he had to compose his works according to the instructions of those who commissioned them, and these sponsors preferred to stifle any such scandals. He sought to satisfy the various players in the conquest and thus collaborated patiently with the leadership of the Army of Africa. At the same time, he was vigilant in the task of safeguarding complete creative freedom for himself. Within his experience from the 1840s, he separated out the domain of artistic practice from that of his relations with military people.

5. Horace Vernet (1789-1863), Chasse au lion (Lion hunt), 55.8 x 80.5 cm, lead pencil and watercolor with white gouache highlights on bistre-colored paper, Prints and Drawings Office, Strasbourg Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 77.986.0.139.

As he was finishing The Battle of Isly, he wrote a letter to Pélissier, the most decried officer in France, that revealed his desire for independence.[ref]Letter from Vernet to Pélissier, April 1846, conserved at the Empéri Museum in Salon-de-Provence (no inventory number). I thank Mélanie Vanderbrouck for having indicated this source to me.[/ref] He apologized to Pélissier for having represented him in the picture’s background, even though the action deserved to figure right out front, before the viewers’ eyes. He also took full responsibility for this choice requiring a certain sense of artistic verisimilitude. “I have just finished Isly; unfortunately, your brigade is far removed from the foreground and I couldn’t separate you from it at the moment when it was the most engaged, in order to place you in front. Here we have the harsh necessity to which I was reduced, as against the desire to paint you during one of those days when the Arabs felt the power of your warrior spirit.” Vernet then stated his total support of the officer regarding the past massacre in the caves and expressed his “indignation at the shameful way in which certain individuals who fight war only from afar have maligned [the] cave attack.”[ref]Pierre Guiral and Raoul Brunon, Aspects de la vie politique et militaire en France au milieu du XIXe à travers la correspondance reçue par le maréchal Pélissier (Paris: Publication du Musée de l’Empéri, 1968), p. 66.[/ref]

Even though Vernet supported this military man with a gruesome reputation, he remained no less relatively autonomous on the artistic level, acting in accordance with his own artistic intentions. Although numerous personalities condemned the colonial project and although political pressures coming from the anticolonialists persisted, Vernet, along with his military friends, hardened their positions in favor of total conquest. The artist, moreover, was to face a strong critical challenge in particular from Baudelaire, who attempted to demolish the aura surrounding him and his works.

Bibliography

BENJAMIN, Roger. Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism and French North Africa 1880-1930. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

BLAIS, Hélène. “Les enquêtes des cartographes en Algérie ou les ambiguïtés de l’usage des savoirs vernaculaires en situation coloniale.” Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine, 54:4 (October-December 2007): 70-85.

ÇELIK, Zeynep. Urban Forms and Colonial Confrontations: Algiers under French Rule. Berkeley-Los Angeles-London: University of California Press, 1997.

FRÉMEAUX, Jacques. L’Afrique à l’ombre des épées: 1830-1930. Paris: Service historique de l’Armée de terre, 1993-1995.

IRWIN, Robert. For Lust of Knowing: The Orientalists and their Enemies. London: Allen Lane, 2006.

JULIEN, Charles-André. Histoire de l’Algérie contemporaine. La conquête et les débuts de la colonisation (1827-1871). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1964.

LABRUSSE, Rémi. Ed. Purs décors? Arts de l’Islam, regards du XIXe siècle. Collections des Arts Décoratifs. A 2007-2008 Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) exhibition catalogue. Paris: Les Arts Décoratifs, Musée du Louvre, 2007.

MacKENZIE, John M. Orientalism: History, Theory, and the Arts. Manchester: Manchester University Press and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

MESSAOUDI, Alain. Savants, conseillers, médiateurs: les arabisants et la France coloniale (1830-1930). Dissertation written under the direction of Daniel Rivet. University of Paris-I, 2008.

OULEBSIR, Nabila. Les usages du patrimoine: monuments, musées et politique coloniale en Algérie (1830-1930). Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2004.

PELTRE, Christine. L’atelier du voyage. Les peintres en Orient au XIXe siècle. Paris: Gallimard, 1995.

PORTERFIELD, Todd. The Allure of Empire: Art in the Service of French Imperialism, 1798-1836. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

POUILLON, François. Ed. Dictionnaire des orientalistes de langue française. Paris: Éditions Karthala, 2008.

POUILLON, François. Les deux vies d’Etienne Dinet, peintre en Islam: l’Algérie et l’héritage colonial. Paris: Balland, 1997.

SAID, Edward. Orientalism (1978). New York: Vintage Books, 2003

Nicolas Schaub, who has a doctorate in the History of Contemporary Art and has been an “ATER” instructor at the University of Western Brittany and then at the University of Strasbourg, participated in the 2012 exhibition Algérie 1830-1962, avec Jacques Ferrandez at the French Army Museum, Hôtel National des Invalides. He has also contributed to various exhibition catalogues (Daoulas Abbey, Vosges Departmental Archives, Museum of Civilizations from Europe and the Mediterranean [MuCEM] in Marseille). Between 2003 and 2007, he worked as part of the “Art and Architecture of Globalization” program at the French National Institute of Art History. He is currently preparing the publication of his thesis (under the direction of Christine Peltre), L’armée d’Afrique et la représentation de l’Algérie sous la monarchie de Juillet for Éditions Comité des Travaux Historiques et Scientifiques (CTHS)/Institut National d’Histoire d’Art (INHA) in its “L’Art et l’Essai” series.