Fabienne Chevallier studies the connections between architecture, urban planning, hygienics, and politics. Here, she looks at the cholera epidemic of 1932 in Paris, where the inequality before life was confirmed to be a determining factor for inequality before death. The official decrees recommending expensive and inaccessible forms of nourishment—grilled meats and fish—were no more realistic for the destitute than the suggestion to ventilate living spaces.

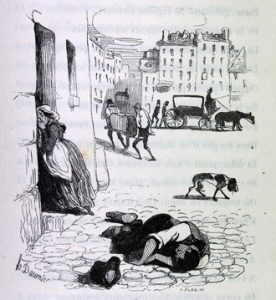

In this process of consciousness-raising and aspiring for more equality, artists played a role by appropriating the event as a figurative motif. In this spirit, Daumier did caricature after caricature. The author offers us the image of a woman wearing a bonnet who flees with a child in her arms and arrives before a doorway painted with a white cross as the allegory of a Social Republic abused by the July Monarchy.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Fabienne Chevallier THE CHOLERA EPIDEMIC OF 1832:

THE PASSION FOR EQUALITY AND THE SOCIAL QUESTION

Late in the month of March 1832, a cholera epidemic struck Paris. It ended in late September, after having brought about the death of more than 18,000 persons (at the time, Paris numbered 800,000 inhabitants). The epidemic came from India, invaded Russia and Poland around 1830, and then arrived in France and England.

Subsequent to the epidemic, Louis-René Villermé’s report on the course of cholera morbus showed that the poorest sections—those situated near the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall), Île de la Cité, and in the twelfth arrondissement of the time—were the hardest hit: inequality before death mirrored people’s living conditions. Yet the egalitarian paradigm was already highly present during the epidemic. What that epidemic revealed was that Les Trois Glorieuses (the three days of revolution in July 1830) were indeed a grand illusion, since the people who supported this revolution had now been unfairly decimated. Art took part in this dramatic shift, appropriating social drama as a new historical subject.

Fermenting the Rage of Equality

The July Monarchy was a fragile regime. This revolution had brought Louis-Philippe to power, but what was to be the revolution’s fate? A journal called La Caricature set the tone on March 1, 1832, a few weeks before the epidemic: “The victorious people had won equality. Promises were made. But its generosity was abused. The people were still in the throes of joy when vile intriguers, men of prey, seized power.”

Chosen for the Presidency of the Council by Louis-Philippe, Casimir Perier succeeded the banker Jacques Laffitte. “Monsieur Casimir Perier, a man of order and wealth, didn’t want to fall into the hands of the people,” Chateaubriand said of him. In the Fall of 1831, the Lyon silk workers’ revolt had been repressed. Louis Blanc saw therein France’s first class war. While Louis-Philippe did indeed purchase Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People after its presentation at the Salon of 1830, this tumultuous icon, which prefigured the French Republic, was quickly relegated to the back of a storeroom.

It was a year after Perier’s arrival in power that this epidemic arose. On March 14, 1832, a note from the Paris police headquarters sounded the alarm: a few cases of cholera had broken out. On the 29th of March, the scourge’s invasion of the city was patent. Ten cholera patients were admitted to the Hôtel-Dieu general hospital overnight, among them, a shoemaker living on Île de la Cité. That evening, during the Mardi Gras festival, a man disguised as Harlequin turned purple and collapsed after having eaten some ice cream. The popular mood on the major boulevards suddenly turned to one of terror.

Egalitarian Scapegoat Figures, Rumors, and Horrors

With a quicker reaction time than is generally admitted, on that same day Paris Police Chief Henri Joseph Gisquet asked a company that had won the bid for city sanitation services to do an additional round of street cleaning in order to clear the streets of garbage and refuse. For, it was known that filth played a role in the spread of the epidemic, even if it was not known why. But the ragmen, who picked up all the rubbish, and who lived on it, resented this measure as the loss of a right. This led to the April 1st riot, which was infiltrated by secret societies.

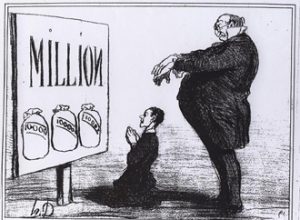

On a handbill distributed on the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, one may read: “Cholera is an invention of the bourgeoisie and the government to starve the people.” Epidemics have always given rise to scapegoats, among them, the Jews. In 1832, the scapegoats were the elites. In chain reaction, a mutiny occurred in the Sainte-Pélagie Prison, after which rumors of poisoning began to spread. They were perhaps fed by the Carlists to destabilize the regime. Still, these rumors triggered six cruel murders, murders of innocent people. Perier, himself stricken with cholera, commented, “That’s not the thinking of a civilized people; it’s the cry of a savage people.”

1. Honoré Daumier, Le choléra-morbus à Paris en 1832 (Cholera-mobus in Paris in 1832). Illustration for François Fabre, Némésis médicale illustrée, vol. 1 (Brussels, 1841), p. 69. Bibliothèque de l’Académie de médecine, call number: 47 337. © Bibliothèque de l’Académie nationale de médecine

Curses and Terror on Both Sides of the Dividing Line Between Rich and Poor

The Archbishop of Paris aggravated the social question by predicting that God would send the cholera epidemic as a chastisement of the people, who were guilty of having “forced out the very Christian king” (Charles X). The press noted right away that the epidemic’s ravages were brought first upon those most unfortunate. This simple fact contained, however, a barely veiled social threat. Filled with moralistic considerations, the decrees that were handed down pointed to idleness, poverty, and alcohol as causes of the illness.

The poor could not follow the instructions given for the prevention and treatment of cholera. As preventive measures, these instructions recommended grilled meats, fish, and the ventilation of living spaces. The price of camphor, the basic medication, shot through the roof. Some rich people, like the banker Alexandre Aguado, Rossini’s patron, left Paris. Heinrich Heine commented in the Augsburg Gazette: “The poor were annoyed to see that money had become, too, a means of protection against death.”

An atmosphere of score settling reigned among classes, as is shown in the following poster that could be read at the Trône tollgate after the ragmen riot: “Remedy against cholera morbus: take two hundred heads from the Chamber of Peers, one hundred and fifty from the Chamber of Deputies, those of Casimir Perier, Sébastiani, and d’Argout, those of Philippe and his son, roll them over the Place de la Révolution, and the air of France and Belgium will be purified.”

The Imagery of the Miracle-Working Prince: A Still-Born Public-Relation Ploy

As a way of indicating his support for the capital’s population, Louis-Philippe decided not to leave Paris. Queen Marie-Amélie sewed flannel belts for cholera patients. The Duc of Aumale, who was ten, passed out free soup. But Louis-Philippe’s image had already been irremediably tarnished by the pear-shaped caricatures done by Honoré Daumier. On April 1, the Royal Prince Ferdinand-Philippe visited the Hôtel-Dieu, accompanied by Perier. The latter was not enthusiastic about the idea of a visit, but he had to resign himself to it, faced with the determination of the prince. Already quite weakened, Perier contracted cholera. This visit was his last public appearance. When he became delirious, one went to fetch Jean-Étienne Equirol, who treated the insane at the Charenton asylum. Perier died on May 16, 1832.

Perier’s illness helped to settle a political score. It stopped the regime’s evolution toward an English-style parliamentary government. The king took back the reins of power. After Perier’s death, Louis-Philippe commissioned from Alfred Johannot a visual rendering of the Hôtel-Dieu visit. The prince is represented there as a miracle-working prince. Behind, Perier seems already stricken with cholera. This painting was never going to play, for the Orléans family, the public-relations role Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (executed by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros in 1804) had played for Napoleon.

2. Honoré Daumier, Maisons marquées pendant une épidémie (Marked houses during an epidemic). Illustration for François Fabre, Némésis médicale illustrée, vol. 1 (Brussels, 1841), p. 265. Bibliothèque de l’Académie de médecine, call number: 47 337. © Bibliothèque de l’Académie nationale de médecine

Medicine, Hovering between Brotherly Devotion and Charlatanism

There was a huge mobilization of the medical profession during the cholera epidemic of 1832. Medical students were requisitioned by the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. Their involvement took place against a background of obscurantism, since the immense majority of the members of the medical profession still believed in the miasma theory and stated that cholera was not contagious. Caring for the sick broke down into two schools of treatment. According to François Broussais, cholera is an inflammation that is to be snuffed out with the ingestion of ice, leeches, and bleeding. For François Magendie, one should, on the contrary, keep the sick person warm. He created a famous punch, Magendie Punch, from a lime blossom-based tea.

Drug trials were developed, sometimes with deadly results, against a background of charlatanism tinged with exoticism: lead-acetate pills, South-American ipecacuanha, and a balm from Iceland were sold in pharmacies, not to mention calefactories. Three medical reviews (Le Journal Hebdomadaire, La Gazette Médicale, and La Gazette des Hôpitaux) attempted to correct these excesses and abuses by giving information on treatments. But examples of charlatanism were already filling the columns of La Caricature. The style, drawn from Molière’s comedies, was to ridicule medical practices: if you are sick, “You must walk a great deal, unless you prefer to stay in bed.” In order to denounce these bad old ways, François Fabre would publish in 1841 the Némésis médicale, with illustrations by Daumier. Closely related to the ideas of François-Vincent Raspail—who demanded a new kind of medical practice, one capable of uniting a republican society—Fabre denounced the negligence of the July Monarchy, which never rewarded the devoted doctors who had attended to the people of Paris during the cholera epidemic. Daumier represented the homes marked by the epidemic: a woman wearing a bonnet flees with a child holding her hand and arrives before a doorway painted with a white cross. One may see therein the allegory for a social republic that had been swindled by the July Monarchy.

The cholera epidemic set the paradigms of equality, the Republic, and justice to work within the Parisian soil. Imbued with a new sense of heroism, the art of Honoré Daumier preceded and accompanied these upheavals in social history.

Bibliographie

Louis BLANC, Histoire de dix ans: 1830-1840, Paris, Jeanmaire, 1882.

Louis CHEVALIER, Le choléra, la première épidémie du XIXe siècle, La Roche sur Yon, Bibliothèque de la Révolutio de 1848, Tome XX, 1958.

Heinrich HEINE, De la France, Paris, Renduell, 1833.

François-Vincent RASPAIL, Histoire naturelle de la santé et de la maladie, Paris, Alphonse Levasseur, 1843.

Fabienne Chevallier, est historienne de l’art (HDR), actuellement en poste au service de la conservation du musée d’Orsay. Elle est membre de l’équipe d’accueil Histoire et critique des arts de l’université de Rennes 2.

Ses travaux ont trait à l’architecture et à l’art du dix-neuvième siècle (jusqu’en 1914), ainsi qu’à l’histoire du patrimoine en France. Ils portent tout d’abord sur les développements de l’idée de nation dans l’art et l’architecture européennes pendant cette période. Elle a publié notamment, avec Jean-Yves Andrieux et Anja Kervanto Nevanlinna, Idée nationale et architecture en Europe 1860-1919, Finlande, Hongrie, Roumanie, Catalogne, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2006 et elle a contribué en 2012 au catalogue de l’exposition sur l’artiste finlandais Akseli Gallen-Kallela, organisée au musée de la ville de Helsinki, au musée d’Orsay et au Kunstmuseum de Düsseldorf (Akseli Gallen-Kallela, une passion finlandaise, musée d’Orsay, 2012.

Dans son habilitation à diriger les recherches (2009) Fabienne Chevallier s’est intéressée à l’histoire sociale de l’architecture au dix-neuvième siècle, en étudiant les liens entre l’architecture urbaine et les politiques d’hygiène à Paris. Cette monographie est publiée en deux volumes : La naissance du Paris moderne. L’essor des politiques d’hygiène 1788-1855, 2012 (ouvrage en ligne à :

http://www.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/histmed/asclepiades/chevallier_2009.htm), et Le Paris moderne. Histoire des politiques d’hygiène 1855-1898, Presses universitaires de Rennes – Comité d’histoire de la ville de Paris, 2010 (prix du meilleur ouvrage de la Société Française d’Histoire de la Médecine en 2010 et prix Jean-François Coste de l’Académie nationale de médecine en 2011).

Son prochain ouvrage, en collaboration avec Jean-Yves Andrieux, s’intitulera une Histoire du Patrimoine monumental. Des sources antiques à l’époque contemporaine. Il sera publié en 2013 aux Presses universitaires de Rennes.