Maurice Fréchuret has just been awarded the Pierre Daix Prize for his book Effacer. Last year, he offered us a preview of his reflections which take an interest, too, in the status of things. In a world where the eye is permanently being solicited, he pays heed to all artists who, since Marcel Duchamp, have decided to erase, burn, cover over, or bury things, not in order to destroy them but, on the contrary, to alert us to the abuses of accumulation, while inviting us to see what is barely visible so that we might gaze again with fresh eyes.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Right of Withdrawal

Maurice Fréchuret

Too often we forget how much we owe to artists, the investigations they undertake, and the proposals they direct our way. We do not know exactly what works of art bring to us, nor in what way they transform our view and our perception of the world. Of course, since Pablo Picasso we are not unaware of the fact that “Painting is not made to decorate apartments,” but it is still with much difficulty that we assign to art the roles it really plays, and we are generally happy to grant the necessity of this practice solely to the individuals who exercise this profession. And yet art reveals itself to be a powerful tool for change whose impact can, when we reflect upon it, easily be confirmed. Our gaze is altered by what artists imagine, by what they let us see, and by the gestures they make. These are so many facts that serve to impose ideas on the world but also to make the world of things undergo significant transformations.

Among these artistic gestures, there is one we wish to bring out because it changes our way of apprehending art, its object, and the surrounding world. In a world in which one’s gaze is constantly being solicited, it is quite paradoxical that the gesture of erasure has become, in the course of the twentieth century and still today, an exemplary artistic practice full of particularly rich developments. From Marcel Duchamp to Robert Rauschenberg and from Marcel Broodthaers to Roman Opałka, numerous artists have practiced erasure and have shown the positive aspects of this gesture, a gesture that, in the other domains of human activity, is so strongly tied to lying, falsification, dissimulation, and bans. In the political field, erasure is a practice most dictators have perpetrated time and again. One has stopped counting the number of documents in which, heroic leaders one day, leaders would soon become traitors whose image had to be banished so that everything, up to and including their past existence, would be made to be forgotten. The damnatio memoriae that, through the use of erasers or scissors, struck Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, Liu Shaoqi, Lin Biao, and Joseph Goebbels is, without any doubt, the surest sign of this sort of historical “correction,” but it applies, too, in the field of the economy and communication. An illustrated magazine’s erasure of an extra fold of presidential flesh and, of more serious consequence, the erasure of a black man from a recent ad are other examples of this sort of falsification associated quite generally with the practice of erasure.

View of Claudio Parmiggiani’s installation, Untitled, 1999, smoke and soot on wood, Art Basel 2013

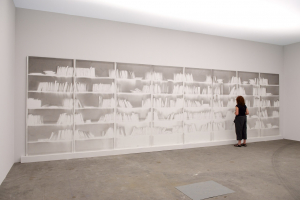

Artists have recourse to this gesture in order to reveal erasure’s capacities for innovation and the depth of its creativity. Claudio Parmiggiani is one of those artists, and the works he would go on to produce along these lines—the Delocazione—are among the subtlest and most exacting on record. Objects—as it happens, often books—are lined up on the shelves of a bookshelf standing against a wall. The space retaining this setup is then hermetically sealed and, in the middle of it, tires are piled up which the artist sets on fire. As expected, the combustion of these tires deposits a thick black acrid smoke on the walls but also on all the elements contained within the space. The books or other objects, once removed, allow but a ghost of themselves to appear. Their presence no longer exists, yet their off-white shapes, thus drawn on the wall, persist within this somber and gloomy universe. As an evocation of a past presence, a reminder of a dissolved materiality, the erasure of objects the Italian artist performs inevitably impairs one’s gaze but furnishes one’s imaginary with some highly lively and penetrating features. Images of the past, which are individual, which are fashioned by the personal history of individuals, may thereby resurface: a photo, a painting, or some other object that, when taken down, leaves marks on the walls of the home in which one has lived are so many occasions to reconnect with those images. Emanating from a collective unconscious as if refreshed by recent history, images can surge forth anew and remind us of the dramatic episodes lived by humanity, which has been tested in its very depths. The ghost of the ladder visible on a wall in Hiroshima and that of bodies pulverized on one side of a Nagasaki house haunt our memory, which, in this instant, finds in Parmiggiani’s works the means to be summoned forth anew.

Eric Cameron, Thick Paintings, Morgane’s White Sugar (1456), sugar packet, layers of acrylic gesso paint, 7.6 × 39.4 × 36.2 cm, begun in 2004

The erasure of things by their mere withdrawal is one of the means artists like Parmiggiani have explored. Other methods of erasure are possible and have been tested. The work of the Canadian artist Eric Cameron is the fruit of another procedure, that of gradually covering over the object, which culminates in its being dissolved beneath the numerous layers that, little by little, mask it, transform it, or annihilate it. In fact, the application of hundreds if not thousands of layers of white acrylic gesso, which the artist deposits on objects (photographic film, a child’s shoe, a rose, a sugar packet, or a head of lettuce) make those objects undergo a veritable metamorphosis—to the point that their initial shapes are sometimes no longer recognizable and their identity as things is completely and inexorably destroyed. The erasure of things selected from among those available within the painter’s everyday world is the fruit of a perfectly paradoxical gesture. The artist paints objects—not as would be done by a painter of still lifes whose objective is to represent them in two dimensions on a canvas but by intervening directly multiple times upon their surfaces, the effect of which is to modify radically their initial appearance. This effort on the part of the painter who makes use only of brushes (we are insisting here on the artist’s status) results, moreover, in three-dimensional shapes that bear a similarity, quite often, to abstract sculptures. The things this Canadian artist has seized upon, and which he has considerably transmuted, are thus twice erased: rendered formally unrecognizable as well as deprived forever of their identity as utilitarian objects.

Daniel Spoerri, Luncheon under the Grass During the Burial of the Trap Picture, picnic organized by the artist in the gardens of the Montcel estate in Jouy-en-Josas, April 23, 1983

After the mode of removal that governs Parmiggiani’s actions and after the neutralizing kind of covering up Cameron practices, burial is a third means for the erasure of things. This is the mode Daniel Spoerri, among other artists, has chosen. In the Trap Pictures this artist began executing in the early 1960s, common objects are extracted from their anonymity and literally upgraded by setting them upright in a vertical position. The 90 degrees that separate the surface of a table from the surface of a wall suffice to confer a new identity upon these objects and make them partake of the plasticity of the wooden panel to which they have meticulously been glued. They thereby fully become pictures in their own right. Those objects guests brought to the large picnic the artist organized in 1983 in the park of the Montcel chateau in Jouy-en-Josas near Versailles would undergo quite another fate. The utensils specially chosen by the guests to participate in this meal were not to be returned to their owners, for the place settings, plates, glasses, dishes, and other containers were going to be buried, at the end of the meal, in an open trench Spoerri had previously dug.

Daniel Spoerri, Luncheon under the Grass During the Burial of the Trap Picture, Jouy-en-Josas, gardens of the Montcel estate, April 23, 1983

Covered by shovelfuls of dirt each guest was invited to cast over them, the objects in question were quite quickly going to disappear from view, as if erased by the thick covering of soil that engulfed them. Common or unique, displaying or not displaying the personality of the guest, these objects, buried under several feet of dirt, were to remain in place on the site for a number of years, until the artist himself decided to undertake an archeological dig and bring to light the vestiges of this much-talked-about banquet. In no way did the rediscovery of these objects, some twenty-three years later, weaken the initial project of this Burial of the Trap Picture, which became a Déjeuner sous l’herbe (Luncheon under the grass) so closely connected to the artist’s own biography. Either a mere reminder or a genuine outlet for his feelings, Spoerri’s project, executed in the joyous and playful form of a banquet, cannot help but be related to the frightening scene in which his father, Isaac Feinstein, was shot by Nazi Einsatzgruppen, those militarized Third Reich political police units charged with the mission of exterminating (in a Holocaust by bullets) the handicapped, Gypsies, Jews, and other categories of the population deemed obstacles to the project of Aryan purity. The trenches dug prior to these massacres thus became burial pits into which fell the “pieces” (to use the name by which the Nazis designated Jews, who were treated as “things” and piled up like “packages”). It is in such a reversal of viewpoint that The Burial of the Trap Picture/Luncheon under the Grass gains its full force and that a response is given, in the form of generous social interaction, to terror and to the tragedy of history.

In a world where the things that accompany individuals’ existence have been transformed into a vast and anonymous accumulation of commodities and where “see all” has become a genuine, overriding imperative, some artists have chosen, paradoxically, to erase and to remove from one’s sight elements whose materiality is, as a result, as if called into question. Parmiggiani, Cameron, and Spoerri, but also Broodthaers, Jochen Gerz, Félix González-Torres, and Ann Hamilton, among other artists of various generations, have exercised this “right of withdrawal” and restored to artistic experience the roles that commit it to the human community, roles that it can sometimes forget to assume and without which it ceases to be the sort of invigorating exercise of which we have so great a need.

Maurice Fréchuret is an art historian and a French National Heritage Chief Curator. With a doctorate in Sociology and another one in Art History, he was curator of the Saint Étienne Museum of Modern Art from 1986 to 1993 and then of the Picasso Museum in Antibes from 1993 to 2001. Director of the CAPC Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux from 2001 to 2006, he was named curator of French Twentieth-Century National Museums in the Alpes-Maritimes département of France (2006-2014). Fréchuret has organized numerous exhibitions in the course of his career and written for numerous catalogs. His latest work, Effacer, paradoxe d’un geste artistique (Presses du réel, 2016) received the 2016 Pierre Daix Prize. He is, in addition, the author of Exils (in collaboration with Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2012), Les Années 70, l’art en cause (Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2003), L’Art médecine (in collaboration with Thierry Davila, Picasso Museum, Antibes, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), L’Envolée, L’enfouissement (Skira, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1995), La Machine à peindre (Jacqueline Chambon, 1994), and Le Mou et ses formes (École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 1993; Jacqueline Chambon, 2004).