We know Antje Kramer because of her thesis on Les Nouveaux Réalistes en Allemagne (1957-1963) (The New Realists in Germany, 1957-1963), forthcoming from Presses du Réel. Here, she studies the figure of the artist as teacher in the 1960s and 1970s through the writings and actions of Yves Klein, George Maciunas, Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Wolf Vostell, and Joseph Beuys. Concerned above all with bringing about radical societal changes while dreaming of an ideal new world to be born from a universalist form of education in which equality would reign, they were unable to avoid the contradictions of utopians belong to an elite that guarantees its superiority by becoming artists. Going back through history, Kramer brings out the peculiarity of this era in which art was no longer conceived in terms of a transmission of artistic knowledge and skills but instead as a laboratory for the creation of a new world and a new man.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

The Artist as Teacher:

On the Egalitarian Myths of Arts Education After 1960

Antje Kramer

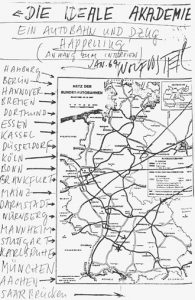

In the 1960s and 1970s, the figure of the artist as teacher was to set its mark on the work–at least the theoretical work–of a good number of artists who had come out of the new avant-garde movements of the time. Through their writings and actions, they exhibited, like the initial avant-garde movements before them, a desire to provoke societal changes that, at their pinnacle, would surely give birth to a new man: an ideal man in an ideal society that, it too, would be the fruit of a universal, free, and egalitarian form of education and training. Turned toward the world of tomorrow, these conceptions of an “ideal academy” are to be understood as forward-looking visions, ones faithful to the mission these artists had assigned to themselves: the instauration of a new unity between art, nature, and society. While Yves Klein had dreamed, as early as 1959, of creating a “school of sensibility” that would realize his overall concept of an immaterial architecture, George Maciunas envisaged the founding of a “Fluxus Bauhaus” on a Carribean island and Friedensreich Hundertwasser, with Arnulf Rainer, got down to the business of creating the “Pintorarium,” an academy “half way between a urinal and a pinacotheca.”[ref]Hunderwasser, quoted by Pierre Restany in Le Pouvoir de l’art. Hundertwasser, le peintre-roi aux cinq peaux (Cologne: Taschen, 2003), p. 24. [/ref] Wolf Vostell, in turn, imagined in 1969 an “ideal academy” in the form of a mobile laboratory that would travel from town to town. Joseph Beuys–the only one of these artists to have actually benefitted from some serious teaching experience–sketched out the image of totally free school that would be able to take shape specifically through the creation of a new political party.

What is striking when one considers these various conceptions, which for the most part remained in the state of rough drafts, is how they went beyond the very concrete problems involved in arts education so as to favor the instauration of a site of universal education. Far from being reformers of an already established system, these artists clearly showed themselves to be utopians. In claiming a presumably higher status qua artist, they took a stand against the established materialism while promulgating ideal, indeed spiritual, values that were supposed to guarantee the greatest good for the greatest number. A survey of these educational missions, whose history remains to be written, raises a certain number of questions.

Universal Ambitions

Joseph Beuys during a meeting of his German Student Party, 1969, in front of the Düsseldorf Academy.

First of all, while such reflections were born of a need to extend artistic practice to life itself, they testify thereby to a radical redefinition of the problematic of art. Well beyond the confines of individual artistic genius, art is understood here as an egalitarian social practice grounded on the principles of dialogue, democracy, and shared creation. All these projects testify to an extremely broad approach to education in which multidisciplinarity and a generalist training take precedence with the goal of allowing the complete development of people’s creativity. Whereas, for Klein, students would have to take on, alongside artistic subjects, both the martial arts and public relations, Beuys integrated the natural sciences and economics as much as sociology into his plan, and Vostell made room for new media. These ideal academies all shared the same objective: that of no longer forming artists, but instead “complete men,” ones capable of transforming society. In 1969, Beuys summarized this calling in an interview:

“[I]f one says, aesthetics equals the human being, the human being is still an artist, it mattering little whether he becomes an accepted specialist in this field, of significance for the history of art, or not; that’s just secondary. –So, it’s almost the opposite: man enters here [into the academy] perhaps as an artist and leaves the institution with the intention of studying techniques. In the meantime, however, he has received important information about man himself. This process can be initiated on the artistic side. –But it would also have to be initiated through science.”[ref]Interview with Friedrich Heubach, facsimile reprint published in Johannes Stüttgen, Der ganze Riemen. Der Auftritt von Joseph Beuys als Lehrer, Hessisches Landesmuseum (Cologne: Walther König, 2008), pp. 465-66.[/ref]

Let us recall, however, that none of these projects offered any details about the actual organization of the curriculum or about individual classes.

Historical Background

Yves Klein during his lecture at the Sorbonne, June 3, 1959.

While it is true that, in an underlying and unconscious way, these different models of schooling revived the distant tradition of the first Platonic academies, we still must inquire about the historical models that served to consolidate these images of a general life-apprenticeship. Most of the references are difficult to make out, for only hints of them are to be found in these conceptions (we are thinking, in particular, of the tacit influence of anthroposophical education on Beuys). But in them there remains a specific appeal to history. In drawing up the curriculum for their “school of sensibility,” the French artist Klein and the German architect Werner Ruhnau explicitly appealed on this occasion to the Bauhaus in order to present their own project as a space for emulation that would, faithful to the practice of their predecessor, gather together international artists of all kinds. Both of them started off with the idea of a revival of architecture, which had already been at the center of the reforming efforts of Walter Gropius. Yet, when one looks closely, this “crystal symbol of a new faith”[ref]Walter Gropius, “Programme of the Staatliches Bauhaus in Weimar” (1919), in Ulrich Conrads, Programs and Manifestoes on 20th-Century Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1971), p. 49.[/ref] conceived by Gropius in reality served merely as a consensus-building historical prop that was grounded, to say the least, on a quite superficial familiarity with that chapter in the history of avant-garde movements. It was indeed a matter of consensus-building, since such general mentions of the Bauhaus were part of the broader discourse being produced in post-1945 Western European and American historiography, which sought to find some symbolic common denominators–such as “modern rationalism,” the goal of “social progress,” and deeply “democratic” motivations–in the efforts of avant-garde movements.[ref]See on this score, in particular, Kathleen James-Chakraborty, ed., Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). [/ref] During the Nineteen-Fifties, only the Hochschule für Gestaltung (school for creation and design) in Ulm–which was financed in part by the American authorities and run by Max Bill, a former student at the Bauhaus Dessau–had been able to establish itself, until its closing in 1968, as the most immediate guarantor for the survival of the progressive legacy of Gropius and his FRG colleagues.

Teaching as Total Artwork

Wolf Vostell, Sketch of the Route of the Ideal Mobile Academy, January 1969.

Since art was longer grasped in terms of a transmission of artistic knowledge and skills, it thenceforth manifested itself through the concepts of collaboration, communication, and social action. It is exchange that is to act as the artwork, as Vostell, in turn, prognosticated in 1969:

“I imagine the academy of the future as a mobile and flexible counseling unit, for the art of the Seventies will require a legal counselor and a psychologist. Furthermore, it is my conviction that the art of the final decades of this century will be immaterial, and so, starting in the early Seventies, I will stop producing objects and actions so as not to devote myself any longer to anything but ideas.”[ref]Interview conducted by Friedrich Heubach; facsimile reprint published in Vostell, Fluxus-Zug, das mobile Museum Vostell, 7 Environments über Liebe, Tod, Arbeit, Dagmar von Gottberg, ed., Sekretariat für Gemeinsame Kulturarbeit in Nordrhein-Westfalen (Berlin: Fröhlich und Kaufmann, 1981), p. 152.[/ref]

What would happen then to the individual status of the artist in this space that is clearly dedicated to the empty place of democracy? Will this status establish him as at once initiator, professor, and missionary? Although, from the standpoint of their political positions, Beuys, Klein, and Vostell were poles apart and diverged on numerous points regarding their respective commitments, all three of them displayed a hypertrophied approach to artistic creativity that was said to be ultimately the only way to succeed in changing the world. Their imaginary academies and, by way of consequence, their teaching activity, claimed the status of “total artwork.” These academies were said to have finally gone beyond the problematic of art and achieved “social sculpture,” as Beuys defined it, so as to constitute immaterial masterworks of the spirit. Indeed, Beuys himself did not hesitate to define his teaching practice as his greatest work of art. And when he went about explaining his pictures to a dead hare, was that not testimony to his supernatural pedagogical talent?

The Student Without Qualities

In light of these totalizing approaches to pedagogical transmission, a final point remains to be made. Whereas these artists had, in their speeches and actions, thought through their individual educational role and experimented in very concrete ways with it, they neglected to nuance the role of their direct partner in social dialogue. The student or pupil was envisaged in absolutist terms that seemed to render obsolete any nuanced questioning about his status or his individual future. Thanks to these in vivo experiments in collaboration and exchange within such an academy, he is supposed to become that faceless “complete man” who is capable, beyond any particular distinctive biographical or psychological characteristics whatsoever, of acting on the future. Thus, Beuys’s student and faithful assistant Johannes Stüttgen, having learned his lessons well from Beuys, did not hesitate to report his occupational status, in complete seriousness, as “student of Beuys.”[ref]Interview published in Petra Richter, Mit, neben, gegen. Die Schüler von Joseph Beuys (Düsseldorf: Richter, 2000), p. 207.[/ref] If the ultimate development of the egalitarian pedagogical ideal thus halts at the mirror stage, one cannot help but reinforce the role of the teacher [le maître] while repeating the claim that democracy is indeed very funny. [ref]We are making reference here to Joseph Beuys’s Demokratie ist lustig, a screen print created by Klaus Staeck from a news photo taken after the occupation of the Secretariat of the Düsseldorf Academy, in October 1972, which led to Beuys’s firing. [/ref]

Bibliography

DUVE, Thierry de. Faire École (ou la refaire ?). Dijon and Geneva: Les presses du Réel/Mamco, 2008.

HULTÉN, Pontus, and Daniel BUREN. Eds. Quand les artistes font école. Acts of a colloquium at the Institut des Hautes Études en Arts Plastiques. 2 vols. Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2003.

RICHTER, Petra. Mit, neben, gegen. Die Schüler von Joseph Beuys. Düsseldorf: Richter, 2000.

SEMIN, Didier, and Marie SiCHÈRE. Eds. Yves Klein. Le dépassement de la problématique de l’art et autres récits. Paris: École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2003.

STÜTTGEN, Johannes. Der ganze Riemen. Der Auftritt von Joseph Beuys als Lehrer. Hessisches Landesmuseum. Cologne: Walther König, 2008.

Vostell, Fluxus-Zug, das mobile Museum Vostell, 7 Environments über Liebe, Tod, Arbeit. Dagmar von GOTTBERG. Ed. Sekretariat für Gemeinsame Kulturarbeit in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Berlin: Fröhlich und Kaufmann, 1981.

Of German origin, Antje Kramer is an assistant professor in the History of Contemporary Art at the University of Rennes II. Studying under Pierre Wat at the University of Provence Aix-Marseille I, she completed her doctorate in 2009 on Les Nouveaux Réalistes en Allemagne–réalités et fantasmes d’une néo-avant-garde européenne (1957-1963) (The New Realists in Germany: realities and fantasies of a neo-avant-garde movement, 1957-1963), which is forthcoming in 2011 from Presses du Réel. In her work, she evinces a specific interest in the relationships between avant-garde and neo-avant-garde movements and in the archives and writings of twentieth-century artists. In particular, she has published an anthology of writings accompanied by commentaries: Les Grands Manifestes de l’art des XIXe et XXe siècles (Paris: BeauxArts Éditions, 2011).