Katia Schneller recently defended an excellent dissertation on the constructions and deconstructions of artistic categories in New York between 1966 and 1973. In her thesis, Schneller described the proliferation of all kinds of labels, from Minimal Art to Postminimalism, passing by way of Conceptual Art and the Anti-Form movement. Such labels offer less an account of clear categories of new artistic practices than an understanding of how the notion of style was being redefined. This way of mimicking the breaks made by various avant-garde movements has served as a prelude to the situation we have today, where the attribution of names corresponds to an attempt to define the nature of artistic activity. The project of Vanessa Théodoropoulou and Tristan Tremeau here is to study what is covered by such nominalism.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of December 10th 2009

Art that criticizes Art?

Tristan Trémeau

A few authors, including myself, have identified and criticized the emerging art of the 1990s, notably described as relational by Nicolas Bourriaud[ref]Nicolas Bourriaud, Esthétique relationnelle (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 1998).[/ref]. For us, such art pertains to a consensual ethics whose aim is mediatory, even pastoral, in character[ref]Tristan Trémeau, “L’artiste médiateur,” Art Press, special issue 22 (November 2001: “Écosystèmes du monde de l’art”): 52-57; Amar Lakel and Tristan Trémeau, “Le tournant pastoral de l’art contemporain,” in L’art contemporain et son exposition, vol. 2, Acts of the international colloquium at the Georges Pompidou Center, October 2002 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007): 101-23; Jacques Rancière, Malaise dans l’esthétique (Paris: Galilée, 2004); Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October, 110 (Fall 2004): 51-79.[/ref]. Within this context of challenging the ethical and aesthetical biases of a kind of art that aims at restoring communitarian feelings through the production of participatory “micro-utopias,” a Hungarian artist, Ferenc Grof (b. 1972), and a student of curatorial practices, the Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Naudy (b. 1982), conducted some research in 2004. Their research led to them to design an exhibition whose ambition was to compare Socialist Realism and relational aesthetics, and more generally, approaches that question the aesthetic forms of sociability and political art. Grof and Naudy interpreted these forms as involuntary parodies of the aesthetic ideology of Socialist Realism: moralizing representations of models of “proper” sociability as attainable utopias (in the case of Rirkrit Tiravanija)[ref]This propagandistic aspect is even more noticeable in the photographs of Tiravanija’s installations, as analyzed by Frédéric Wecker and Benjamin Thorel, “Quand les usages deviennent formes de vie,” Art 21, 1 (December 2004-February 2005): 14-21.[/ref] and a taste for monumentality, group gatherings, and agitprop (in the case of Thomas Hirschhorn). A reversal of the term Socialist Realism, Société Réaliste was the title for this radically critical and negative curatorial project–which, however, did not see the light of day, since it was converted into an artistic project Grof and Naudy treated positively: the creation of an artistic cooperative that produces objects–works, texts, exhibitions, lectures, and so on[ref]Read Niels Van Tomme’s interview with Société Réaliste, “Siding with the Barbarians,” Foreign Policy in Focus: www.fpif.org/articles/siding_with_the_barbarians (Washington D.C., June 15, 2009).[/ref].

Critical Reversal of Micro-Utopian Practices

Fig.1. Ponzi’s office, TRAFO Gallery, Budapest, 2006. cliché : Société Réaliste.

The main critical methodology of Société Réaliste’s artistic project is the creation of fictive institutions that operate as offices of investigation, production, and communication dealing basically with the political economy of forms (and the economy of political forms) as well as the material and symbolic economy of art.[ref]Among these numerous fictional offices may be counted MA (Ministry of Architecture), which conducts investigations into spatial policies; Transitioners, which presents itself as a political design agency; and EU Green Card Lottery, which proposes an immigration policy for Europe. See their site: www.societerealiste.net [/ref] Among those fictive institutions, the PONZI’s agency, created in 2006 for a series of exhibitions which were entitled How to Do Things? In the Middle of (No)where and which were held in museums and art centers in Budapest, Bucharest, Kiev, Copenhagen, and Berlin, is undoubtedly the one that most clearly resumes the concerns of their aborted curatorial project. Indeed, the ambition of How to Do Things? was to inquire into the possibilities of social art with micro-utopian aims, in continuity with the assumptions of 1990s ethical art. Société Réaliste responded to this expectation through parody by proposing a financial instrument and some marketing methods that would be applied to art, presenting them as means to achieving economic autonomy.

Fig. 2. Ponzi’s first franchisee classroom, Center for Contemporary Art, Kiev, 2006. cliché : Société Réaliste

PONZI’s is laid out like a game. In order to participate therein, one has to buy coupons and then convince one’s acquaintances to visit the exhibition showing PONZI’s by giving them one of the purchased coupons. When they visit the exhibition, these persons turn in their coupons to the PONZI’s bureau. The winner is the person who will have sent the largest number of visitors. PONZI’s second activity consists in selling franchises to artists–that is to say, the right to use this game, its rules, its visual identity, its logo, its color chart. The main model inspiring Société Réaliste is the one invented by Charles Ponzi in Boston in 1919.[ref]Charles Ponzi was born in1882 in Lugo, Italy and died in 1949 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. His swindle resulted in approximately 40,000 victims who were attracted by his promise of 30 percent interest on investments over 45 days and 240 percent over a year.[/ref] Ponzi invented the pyramid scheme that consists in winning over investors with a rhetoric specially adapted to them so that those investors might finance nonexistent productions. In principle, the first investors are paid by the next group of investors, the second group by the third, and so on. This setup–which holds out the possibility of extravagant returns on investments in the absence of any “real” products–was recently brought back to light by the Madoff investment scandal.[ref]Born in 1938 in New York, Bernard Madoff is an American businessman who was arrested by the FBI and indicted in December 2008 for a Ponzi-type scheme.[/ref]

A Satire of the Relational Economy

Fig. 3. Ponzi’s managers training room, CIAC, Bucarest, 2006. cliché : Société Réaliste

This setup is scathingly ironic: proposing as a social utopia an ultraliberal financial model, itself inspired by a model that makes it difficult to make out the boundaries between legal and illegal investment practices and sales,[ref]To generate PONZI’s, these artists were also inspired by some legal financial instruments and multilevel marketing practices (for example, the American direct sales companies Amway or Avon), as well as casino and banking systems.[/ref] from the start runs counter to the gift ethic and the altruistic benevolence promoted by the current forms of micro-utopian art. Now, what strikes me about PONZI’s is that this setup is also a satire of the relational economy, one that sheds light, in a more general way, on the dominant institutional and commercial mechanisms of art today. Such an economy operates for the benefit of the members of a network, in line with Jacques Godbout’s definition of networks in relation to the way the gift economy has evolved:

“Networks quite simply have no public. They concern regulative processes that address an ensemble of members. That is why it can be said that a network operates in self-regulatory fashion. It does not regulate a public audience but, rather, members, that is to say, individuals who belong to one and the same ensemble. This absence of a producer-user split, which is characteristic of networks, is inherent in the communitarian model.”[ref]Jacques Godbout, in collaboration with Alain Caillé, L’esprit du don (Paris: La Découverte, 1992).[/ref]

When Fiction Meets Reality

Fig. 4. Ponzi’s board of directors, NIKOLAJ, Copenhague, 2006. cliché : Société Réaliste

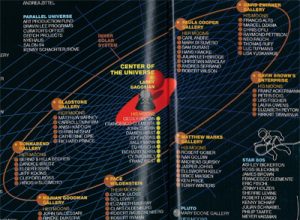

PONZI’s may be understood as a critical disclosure of this relational and franchise-based economy. Moreover, the utopia of artistic financial autonomy, which PONZI’s brings out in fictional fashion, is not unrelated to the project of setting up a mutual-aid program among artists, which was proposed “in real life” by a financial institution that presents itself as a pension fund for artists. Created in 2004, the Artist Pension Trust (APT) consists of eight pension funds spread over the world, the ambition of each one being to set up a fund of 2,000 works invested by 250 artists who have been selected by curators. Once the number of 250 artists has been attained, a special committee is to proceed to sell some works, 40 percent of the proceeds of which go back to the artist, 32 percent being spread among the other members of the APT to which the artist belongs and 28 percent going to APT. Operating as a kind of lobby, APT promises to do everything in its power to assure the sales level of the works and guarantee a reassuring financial annuity for the artists admitted into this program. The curators play a determining role as procurers of artists and as credible intermediaries (all of them being internationally known), but also as promoters of artists (they can organize exhibitions of APT works, presenting them in shows of the institutions they direct or in places where they work freelance). If one compares APT and PONZI’s, APT operates according to the same model and with the same mechanisms as the former’s critical satire of the dominant mechanisms of the art market: the credibility of middlemen (the curators) and the credulity of the investors located at the base of the pyramid (the artists). Moreover, while the marketing of APT to its clients (the artists) works at once on the ethical and utopian levels, the names of the investors at the top of the pyramid are unknown and no public information is provided as to what profits they might draw therefrom.

Fig. 5. Model, Artist Pension Trust. Source: http://www.aptglobal.org.

When I noted APT’s existence in a recent article, some readers thought that APT was fictional.[ref]Tristan Trémeau, “In art we trust. L’économie participative dans l’art,” L’Art Même, 43 (2nd trimester 2009): 3-7.[/ref] Why? With a lot of nerve, APT magnifies all the dominant market traits of the main visible aspects of today’s art world: conflicts of interest, insider trading, and an overemphasis on the role of curators. As such, APT seems to me to be a perfect case study today if one wishes to adopt a critical and theoretical approach with the aim of shedding light on recent changes in the art world and, in particular, on the redefinitions taking place in artistic statuses, identities, and economies. From this perspective and from the standpoint of my current research, Société Réaliste’s critical premonition and lucidity[ref]Premonitory, since Grof and Naudy did not know of the existence of APT when they designed PONZI’s. Later contacted by the fund, which extended them an invitation, they declined to participate in it...[/ref] prove to be of precious value, and PONZI’s turns out to be a lovely thinking machine.

Bibliographie

Bishop, Claire. “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics.” October, 110 (Fall 2004): 51-79.

Gatti, Étienne. “Spéculation/APT: le fonds qui valait 3 milliards.” Particules, 26 (October-December 2009): 2-3.

Godbout, Jacques T., in collaboration with Alain Caillé. L’esprit du don. Paris: La Découverte, 1992.

Kollewe, Julia. “Portrait of the Artist as an Older Man–This Time with a Pension.” The Guardian, September 18, 2009: 6.

Lakel, Amar and Tristan Trémeau. “Le tournant pastoral de l’art contemporain.” In L’art contemporain et son exposition. Vol. 2. Acts of the international colloquium at the Georges Pompidou Center, October 2002. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2007: 101-23.

Lebovici, Elisabeth. “Un projet de société.” Multitudes, 35 (Winter 2009).

Moineau, Jean-Claude. “Étant donnés.” In Contre l’art global. Pour un art sans identité. Paris: Éditions Ère, 2007.

Rancière, Jacques. Malaise dans l’esthétique. Paris: Galilée, 2004.

Salamon, Julie. “New Pension Fund Seeks to Give Struggling Artists a Taste of Long-Term Stability.” The New York Times, July 20, 2004.

Société Réaliste. “The Great Karaoke Swindle.” In How to Do Things? In the Middle of (No)where. Frankfurt/Main: Revolver Publishing, 2006.

Trémeau, Tristan. “L’artiste médiateur.” Art Press, special issue 22 (November 2001: “Écosystèmes du monde de l’art”): 52-57.

Trémeau, Tristan. “Société Réaliste. Nouveaux entrants.” Art 21, 15 (December 2007-January 2008): 42-49.

Trémeau, Tristan. “In art we trust. L’économie participative dans l’art.” L’Art Même, 43 (2nd trimester 2009): 3-7.

Van Tomme, Niels. “Siding with the Barbarians” (interview with Société Réaliste). Foreign Policy in Focus: www.fpif.org/articles/siding_with_the_barbarians (Washington D.C., June 15, 2009).

Tristan Trémeau is a professor of history and theories of art at the École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts of Quimper and at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels. He is, in addition, a junior lecturer at the University of Paris 1-Sorbonne as part of the “Master 2 Pro” program in the Sciences and Techniques of Exhibitions. Holding a doctorate in art history (Charles-de-Gaulle Lille 3 University, 2002), his activities as an art critic since 1995 have led him, after Ddo and Art Press, to join the editorial committee of Art 21 (France), to be a columnist for ETC (Canada), a regular collaborator for L’Art Même (Belgium), and a member of the reading committee of the scholarly review La Part de l’Œil (Belgium). His critical writings concern in the main contemporary pictorial issues and the aesthetic and ideological stakes of present-day art. He is currently working on his first book, which is devoted to the economy of art. His most important articles are to be found in the archives of his blog: http://tristantremeau.blogspot.com.