Bringing together someone involved in the world of art and an economic specialist is one of the ground rules for our seminar this year.

Simon Njami is well known for the texts he has written and for the exhibitions he has organized. We are indebted to him, in particular, for an African self-definition of Africans’ sense of contemporaneity, freed from Western criteria. Here, he offers a Deleuzean reading of the intransigent rules of the international art market.

The economist Philippe Petit responds to him that as things go for art so do they go for everything else–with the slight proviso that the economic world cannot–even if it wanted to–domesticate everything. He reminds us that the community of economists has a hard time defining what a market is and how values are formed therein: the art object, it seems to him, occupies a unique place there, if only because the value assigned thereto goes far beyond its mere financialization. A work of art would thus be, according to him, a sort of symbolic rampart grounded in an empathic dimension open to the problems of the other, which would make it a favorable site for citizen appropriation.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of October 1, 2009

The Principle

and the Reality

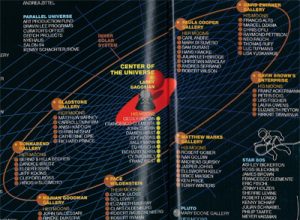

Simon Njami

The establishment of the value of a work before the artist who has produced it enters into commercial circulation and becomes subject to the law of supply and demand corresponds to no economic rule. It would be in that case a matter, rather, of a combination of circumstances that leads to the choice of one or another. For, in fact, it is not a matter so much of choosing a work as of admitting an artist into the highly closed circle of the art market. Contemporary art nonetheless obeys a certain number of rules that are like so many étagements, or layerings, to borrow the Deleuzean expression, and contact surfaces. In this scheme, a series of events go to establish and confirm a value that, whatever the chosen mode of consecration, will in principle remain random, insofar as no historical anointment has occurred. Biennales and major exhibitions, museums, critics and curators, later art fairs and galleries constitute the framework for this transubstantiation of a new kind.

At humanity’s beginnings, art was humble in its approach. It did not analyze itself and did not detach itself from its initial gesture. It was not the object of scholarly commentaries, since it was a natural, everyday expression that partook of the very definition of humanity. Painting was a gesture as basic as drinking and eating. It went unquestioned. Men did not intend to compare themselves with the Great Architect but wished to grant him the place they thought he deserved. Art was collective, anonymous. The gesture was stronger than its result. Then came the moment when, like an impudent Prometheus or an Eve avid for knowledge, man rebelled and sought to become the master of his own fate. Chased from the Garden of Eden, or doomed to have his liver devoured for eternity, man fell into the trap in which Narcissus was caught. He thought himself omnipotent. And the result of this transformation is that the artist started to sign “his” work, substituting thereby the name for the gesture. Some have even seen in the artistic act the “celebration of the death of God.” Indeed, what would one still have to do with a creator of whom one has become the equal? Does one not say of an artist that he is a “creator”?

So, let us summarize. The individuation of the artist and the incarnation of the work constitute the first stage in the establishment of an arbitrary standard as a universal rule. And the complexity–or, to employ the fashionable term, the illegibility–of the contemporary-art market is no doubt but the indirect consequence of an original offense. At art’s birth is to be found an ontological approach that has today been replaced by concepts of discouraging aridity. In the contemporary era, language–which, according to Henri Delacroix, “transforms the chaotic world of sensations into forms and representations”–privileges representation sometimes to the detriment of form. Every representation being only a subjective projection, the resulting interpretations could have no “scientific” value. The contemporary world nonetheless creates a split between the creator and his exegetes, which sets off a series of sometimes laughable misunderstandings. As Jean-Paul Sartre reminds us, “The image . . . it’s a certain way that the object has of appearing to consciousness, or, if one prefers, a certain way that consciousness has of giving itself an object.” [ref]Jean-Paul Sartre, L’imagination (Paris: Gallimard, 1978), p. 19.[/ref]. What was produced by our distant ancestors on cave walls really was art, but it would seem today that, without the gloss that represents the added value of a work or of an artist, there is no room for anything at all. What I am talking about here, let us be very clear about it, applies only to the international art market. It is obvious that outside this highly closed circle, other practices flourish. But that would be the topic for another debate.

As I said, I shall not broach here the question of taste and quality, which we could call aesthetic value, but shall concentrate instead on the other kind of value. For, there exists no universality of taste, and even Immanuel Kant would not contradict me on that point. On the other hand, there exists what I shall call consensus or convention, which determines a “social” value of the work–which, quite often, has no relation to its aesthetic value. The processes applied in these two “revelations” do not always obey the same criteria or rules and sometimes can turn out to be contradictory.

Citroën Picasso C4

We are compelled to analyze the art market either as a phenomenon (Edmund Husserl) or as an event (Gilles Deleuze), knowing all the while that the boundary between the two is sometimes fuzzy, since, as you know, Deleuze made much use of Husserl. What interests me in this system is the fact that, as Paul Ricoeur writes, “At bottom, phenomenology, in bracketing–temporarily or definitively–the question of Being, is born as soon as the way in which things appear is treated as an autonomous problem.”[ref]Paul Ricoeur, Esprit, December 1953.[/ref] » En mettant l’être entre parenthèse, nous ne sommes pas brouillés par des a priori ou des souvenirs. Si je vous dis Picasso, vous ne m’entendrez pas de la même manière qui si je vous disais un « peintre espagnol ». Parce que le nom même de Picasso représente à lui seul une histoire que vous seriez contraints de ne pas ignorer. C’est d’ailleurs l’un des maux dont souffre l’art, et en particulier l’art contemporain. Tout se déroule en vase clos dans ce milieu et les tempêtes qui y surviennent parfois, et qui semblent annoncer la fin du monde, sont, au regard de la « vraie vie », beaucoup de bruit pour rien.

Salvador Dali’s Lanvin publicity.

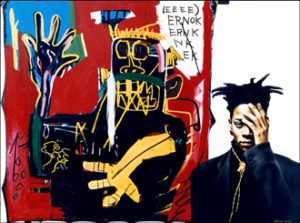

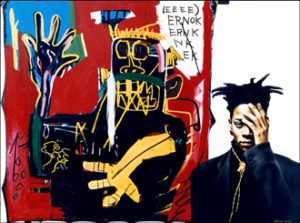

Art–and I am still talking about the kind that is sold between Miami and London, in prestigious art fairs–is not, even if sometimes it involves considerable stakes, a mass phenomenon. It does not constitute a very sexy subject. If I speak of Damien Hirst to my baker, she will look at me stupefied. The aura of the contemporary artist has nothing to do with that of an actor, a singer, or an athlete . . . which confers upon him, straight off, a special position that can be appreciated only by a certain elite group of people. Despite individuation and the phenomena of sporadic crazes that run through the arts community, just a few names have succeeded in leaving the closed field of artistic circles: Picasso in his time, of course, who, after Dali had sung the praises of Lanvin chocolate, lent his name posthumously to an automobile, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Andy Warhol, and perhaps Christo.

Jean-Michel Basquiat in front of one of his works.

I would like to take Basquiat as a case study, for his career illustrates rather well, in my view, all the randomness, the glamor, and the public relations that are tied to contemporary art since the late 1970s. Basquiat, who was of Haitian origin, began his career in the New York subway system and was soon singled out by the New York underground. His signature, SAMO, began to operate as a trademark. Gallery owners sensed a real bargain: this French-speaking black boy had the air of a dandy and his way of expressing himself fit with the times. Starting from there, the machinery was set in motion: group shows, the Whitney Biennial, up to Documenta 7, which was going to hatch three kids, Keith Haring, Miquel Barcelo, and Basquiat. Signs of the times and of mores of the age, Barcelo alone survived the roaring Eighties. Art circles needed new blood. He served it up to them on a platter. Prices for Basquiat works took off all the more easily as the young man displayed a refreshing sense of detachment and made fun of critics and of the world that had crowned him with success. The apotheosis of all this, and I use the word without any cynicism, was his death in 1988 from an overdose at the age of twenty-eight.

But may I not be misunderstood. The art market does not have the power to mass produce Basquiats. The chosen one must still be capable of donning his hero costume. His work, as Deleuze reminds us, has no meaning in the solitude of his studio: “signs remain deprived of any sense as long as they do not enter into the surface organization which assures the resonance of two series (two images-signs, two series, or two tracks, etc.).”[ref]Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense (1969), trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), p. 261.[/ref] The work must therefore be capable of acquiring some commercial value; it must become the object of a consensus among all the agents involved in the operation. All that is needed is for one of them to be absent for the miracle not to occur. The artist and his work would thenceforth no longer have to do anything but gamble on receiving the historical anointment that will write them into the history books. Thus, Van Gogh, whose works were to hit records in auctions long after his death, did not benefit from a consensus capable of winning appreciation for them during his lifetime. In order for the “world of meaning” developed by the artist to be accessible to all at the same time, that world has to meet a certain number of criteria: “And this is the case not only because it hovers over the dimensions according to which it will be arranged in order to acquire signification, manifestation, and denotation, but also because it hovers over the actualizations of its energy as potential energy, that is, the realizations of its events, which may be internal as well as external, collective as well as individual, according to the contact surface or the neutral surface-limit which transcends distances and assures the continuity on both sides.”[ref]Ibid., p. 104.[/ref]

Therefore, there can be no recognized value without a perfect match between production and its “contact surface.” That holds just as well for the market we have attempted to describe, as for the other, parallel markets whose often social, activist, or political character does not necessarily breach the barriers of international recognition. But that world, within which tomorrow’s expressions are tested out (as Basquiat did in his time with graffiti), is the breeding ground without which the great marketplace would have no future. It is upon this breeding ground that, from time to time, influential people will draw in order to provide some novelty for a consumerist world that hastens to burn tomorrow what it had adored the day before. Some artists find themselves compelled to repeat themselves over and over again, trapped as they are by their sudden celebrity. It is only fair–forgive me the moralizing tone here–if others, who are still living in the shadow of the Great Marketplace, have retained their full freedom to create without having to answer to anyone.

Simon Njami is a writer, critic, exhibition curator, cofounder and director of Revue Noire, and a visiting professor at the University of San Diego. He has organized numerous exhibitions, including: Paris Connection, Paris/San Francisco, 1991; L’Afrique par elle-même, photographies, Paris, Sao Paulo, London, Bamako, Washington, Berlin, and Cape Town, 1998/1999 (co-curator); Les Rencontres africaines de la Photographie, Bamako, starting in 2001; Africa Remix, Düsseldorf, London, Paris, Tokyo, Stockholm, and Johannesburg, 2004/2007; Un prisme lucide–photographies, Biennale of Sao Paulo, 2004; first African Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennale, 2007 (co-curator); As You Like it, first African Contemporary Art Fair, Johannesburg, 2008.

Njami is also the author of texts published in exhibition catalogues as well as many of other texts, among which are: “L’invention de la vie,” in Peut-on être vivant en Afrique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2000); Remembrance of Things Past, Ten Years of Debate about African Contemporary Art (Tobu Museum of Art, 1998); An Anthology of African Art: The Twentieth Century (co-editor and coauthor, New York: Distributed Art Publishers/Éditions Revue Noire, 2002); L’Afrique en regards. Une brève histoire de la photographie (editor; Paris: Filigranes, 2005). He is also the author of various short stories, novels, and essays, among which are: Coffin and Co. (1985), trans. Marlene Raderman (Berkeley: Black Lizard, 1987); Les Enfants de la Cité (Paris: Gallimard, 1987); African Gigolo (Paris: Seghers, 1989); Les Clandestins (Paris: Gallimard, 1989); James Baldwin ou le devoir de violence (Paris: Seghers, 1991); C’était Senghor (Paris: Fayard, 2006); Panthéon noir (Paris: Mengès, 2010).