Icon comes from the Greek word for religious images of all kinds, in all materials, and of every dimension. Objects of worship but also objets d’art, icons are linked to the Orthodox faith but also to the history of art. They are the tokens of a worldview that has inspired theologians as well as artists. In this regard, Jean-Claude Marcadé reminds us of the importance of Kandinsky’s discovery of painted and printed icons in those izbas of Northern Russia in which the painter says he learned “not to look at the picture sidelong, but to move within the picture, to live in the picture.” He offers us the keys to understanding the contemporary debate within post-Soviet Russia, where the dual status of icons remains of topical interest. Some Orthodox believers would like to see these venerated images returned to the churches, whereas they had previously been moved to museums where one sometimes see the faithful come to pray. Taking the writings of Nicolai Tarabukin (1889-1956) and Father Pavel Florensky (1882-1937) as their starting points, Marcadé, a great specialist of Russian art, as well as Igor Sokologorsky, a philosopher, study the interpretative aspect of these forms in traditional as well as modern art.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of March 5th 2009

Nicolaï Taraboukine (1889-1956):

The Philosophy of the Icon (1916-1935)

Jean-Claude Marcadé

Icons and Art in the Twentieth Century

Icons have played a key role in the liturgical, theological, and intellectual life of Russia, and this is true in the field of Russian music, as well. Let us recall, among other things, that Kandinsky–that “modernist” par excellence of the twentieth century–said that he already had an existential familiarity with the synthesis of the arts (what at the end of the nineteenth century was called Gesamtkunstwerk or synesthesia) in the izbas of the Vologda Oblast and “in the Moscow churches, and especially in the cathedral of the Dormition and the church of St. Basil the Blessed.” “In these magical houses I experienced something I have never encountered again since. They taught me not to look at the picture sidelong, but to move within the picture, to live in the picture. . . . The “red” corner (red is the same as beautiful in old Russian) thickly, completely covered with painted and printed icons of the saints, burning in front of it the red flame of a small pendant lamp, glowing and blowing like a knowing, discreetly murmuring, modest, and triumphant star, existing in and for itself. When I finally entered the room, I felt surrounded on all sides by painting, into which I had thus penetrated. The same feeling had previously lain dormant within me, quite unconsciously, when I had been in the Moscow churches, and especially in the cathedral of the Dormition and the church of St. Basil the Blessed.”

The choice of these two Moscow churches is no accident. For, both of them are lined with frescos or wall paintings to which are added the wall of iconostases covered with icons.

Malevich. Head of a Peasant (two versions, late 1920s).

The link between icons and the Russian avant-garde manifested itself in a striking way, one could say exoterically, during the Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0, 10 in Petrograd in late 1915, when Malevich installed his “Suprematism of Painting” as the “Red/Beautiful Corner” of Russian Orthodox houses with, as central icon, the Quadrangle (what later on people took to calling the “Black Square against White Background”), which he called “the icon of our times.” This gesture was not meant to signify that it was to be an Orthodox icon, with its liturgical-cultural function (in the sense of the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II, a tradition that has remained intact in the Eastern Church). For, ecclesiastical icons make no sense without the conjunction of the human and the divine in the incarnation of Christ. From this Orthodox point of view, the Malevichian icon, which could be said to manifest only a deus absconditus, is incomplete and has an air of Monophysitism about it.

The Art Historian Nicolai Tarabukin (1889-1956)

Tarabukin is known as a great Soviet art historian who, beginning in 1917, devoted his studies to the innovative arts, and quite particularly to left-wing art (the avant-garde), teaching during the 1920s at Proletkult (Proletarian Culture), at Vkhutemas (Higher Art and Technical Studios), at GAKhN (the State Academy of Artistic Sciences), and at the Meyerhold Theater. In France, people are familiar with translations of his brochures from the very early 1920s: L’expérience de la théorie de la peinture (Towards a Theory of Painting) and Du chevalet à la machine (From the Easel to the Machine), which analyze Soviet Constructivism and Productivism. Most of Tarabukin’s books, like those on the Gothic-Renaissance-Baroque, and the remarkable essay on Vrubel did not appear during his lifetime. The same goes for The Philosophy of Icons, which remained in manuscript form until 1999.

Transfiguration (16th century, Berat Church, Albania).

This work may seem to be a surprising one to come from a theorist and historian of art known rather for his rigorous study of forms and styles who relegated the thematic aspect of works to the background. And this choice of subject matter is all the more surprising as, in contrast to Father Pavel Florensky, Tarabukin was a layman–a believer, certainly, but someone whose experience with prayer, he tells us, was “weak.” And yet here we have a man who declares, in the Second Letter of his Philosophy of Icons (entitled “The Meaning of Icons”): “When applied to religious creativity, aesthetic criteria become, quite suddenly, extraordinarily impoverished and narrow-minded; such criteria can shed light on but a tiny portion of its brilliant content. The aesthete or the philosopher who goes about analyzing religious creativity aesthetically appears a rather pitiful figure of a man, like one who tries to measure the volume of the sea with a dipper. One can, and one should even, speak of an icon aesthetics, but that is but one tiny feature of a very profound content, one problem in a larger whole. Moreover, that feature is conditioned by this whole; the former can be understood only by starting from the latter. And this whole is the religious meaning of the icon.”

Philosophical and Theological Context

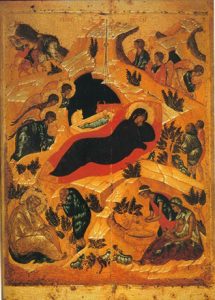

School of Rublev. Nativity (Moscow, c. 1410-1430).

The main part of The Philosophy of Icons is made up of fourteen Letters addressed to his “dear friend,” which is reminiscent of the epistolary format of Father Florensky’s theological dissertation, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters (1914). There is no doubt that the passages in that treatise on art and mathematics gave Tarabukin a decisive impetus to write The Philosophy of Icons, even though he himself was neither a philosopher nor a theologian. Another impulse was to be given to the young Tarabukin by the famous lectures of Prince Yevgeny Trubetzkoy, which appeared between 1915 and 1918 and which took their title from his first lecture, “Speculation in Colors, on Russian Icons and their Place in the Destiny of Russia.” Finally, when he completed his text–clearly sometime in the late 1920s or the early 1930s–Tarabukin undertook a dialogue with Florensky’s Imaginary Numbers in Geometry (1922) and Lev Lossiev’s Dialectic of Myth (1930), traces of which are to be found in The Philosophy of Icons. The head-on opposition to Western art, from the Gothic onward, which is to be found among all Russian authors writing about icons (and particularly in Florensky), becomes in Lossiev and in Tarabukin a violent rejection of Western religious art.

Various Approaches to Icons

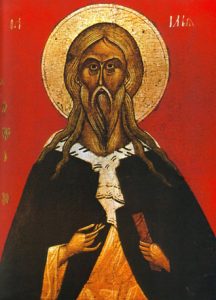

The Prophet Elijah (School of Novgorod, 14th century).

Simplifying things, it could be said that there are four types of approaches to icons–approaches that take into account the specificity of this pictorial art form whose status is totally different from the kind that developed in Western religious painting. It is no accident that Russian vocabulary distinguishes ikonopis (iconography, i.e., the painting-writing of images) and zhivopis (zoography, the painting-writing of life). The first type of approach is theological; icons are here considered to be a “theology in colors,” nay, purely religious. In this category, one could mention Theology of the Icon, a remarkable book by Leonid Ouspensky, the lay icon painter who lived and worked in Paris. The second type of approach is purely philosophical and deals with the issue of images as this issue was raised during the crisis of iconoclasm in the seventh and eighth centuries. Works by Marie-José Mondzain in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s can be mentioned from this standpoint. The third approach involves taking the onto-theological aspect of icons into account, but it does so while placing this aspect of icons in the service of their formal features, icons being the creation of something beautiful, a branch of painting in general. One finds this approach in Father Florensky, particularly in his Iconostasis or, in the West, in the classic book The Icon: Image of the Invisible; Elements of Theology, Aesthetics, and Technique by the German Jesuit scholar Egon Sendler. Finally, a fourth type of approach considers Russian icons as “the beginnings of Russian art,” to borrow a phrase from Nikolai Leskov, the author of The Sealed Angel (1873), a novel that contains a brief treatise on icons. This type of approach could also be linked to The Russian Icon, a book by the Russo-Ukranian painter Alexis Gritchenko that was published in Moscow in 1916, and quite particularly to the pioneering work done by the painter Lev Fedorovich Zhegin (1892-1969), The Language of the Pictorial Work (The Conventions of Ancien Art), which was published posthumously in 1970.

Specificities of Icon Art

Saint John Chrysostom and Saint Paul (Byzantium, 13th century).

Tarabukin’s Philosophy of Icons belongs, in the main, to the first type of approach, the religious one. That is paradoxical, we said, for an art historian who is reputed to be “formalistic”!

In the First Letter, entitled “Paintings and Icons,” Tarabukin declares: “Paintings, like all artworks, are individualistic; in the case of icons, they are prayers expressed in figurative terms. . . . Paintings can have a religious or worldly content. Icons are not only religious but also ecclesiastical.” In the Second Letter, entitled “The Meaning of Icons,” one can read the following: “Worldly paintings act in a contagious way. They carry the viewer away, take him by the throat. Icons are not an appeal; they are a path. They show the ascent toward the Archetype. One does not look at icons; one experiences them and prays to them.” In the Third Letter, “Miraculous Icons,” he states forcefully that “icons, like all rituals, are traditional, canonical, and sanctified by the Church, which, and this goes without saying, would not be the case with just any object.” In the other Letters, Tarabukin lays emphasis (as does Florensky) on the opposition between Catholic sacred art and the Orthodox painting of icons: “Catholic painting narrates; Orthodox iconography prays.” In the Ninth Letter, “The Outward Means of Expressing the Inner Meaning of Icons,” Tarabukin studies in detail the specific techniques of icon painting. The composition of icons stands out on account of its extraordinary self-enclosure. It is a microcosm that contains in itself the macrocosm. It renounces all that is worldly. To this end, it makes use of the composition’s tripartite division, the parallelism of planes, the repetitions, and the symmetry.

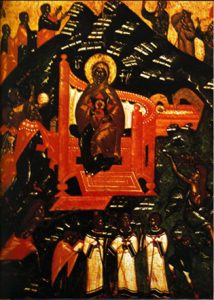

Synaxis of Mary Mother of God (School of Pskov, 14th century).

The composition of icons is indissolubly linked to rhythm. Rhythmic repetitions fulfill the role played by meter in versification and poetic rhyming. Iconography does not think in a Euclidean way. It rejects perspective as a form of expressing an endless space. The world of icon painting is finite. In place of a blue-sky background, icons have a golden background, which symbolizes that the events being contemplated in icons come from outside the delimited boundaries of earthly time and space and are represented, rather, sub specie aeternitatis. “In icon painting, the spatial moment is not separate from the temporal one. The world is understood, it could be said, in the manner of Hermann Minkowski, who says that neither space nor time exists separately, but that the world exists as a n-dimensional spatiotemporal unity. . . . Inverse perspective is the representation of space that is found beyond the terrestrial world, presented in another (i.e., inverted) aspect than the usual one here below. Inverse perspective is the visual representation of the concept of the other world. But as concepts (any concepts) are not representable on their own, but only thinkable, the visual expression of concepts is imaginary. In Imaginary Numbers in Geometry, Florensky says that in representation there are visual images and there are some images that seem to be visual.”

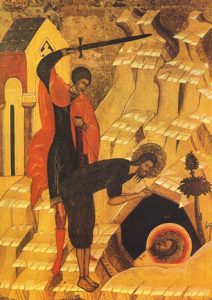

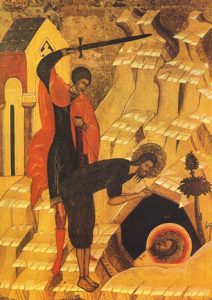

Beheading of St. John the Baptist (Northern Russia, 15th century).

What follows are some quotations from Florensky’s book, which allow Tarabukin to conclude: “The world of icons is, in its own way, real and concrete. In icon painting understood as meaning, subjectivism and psychologism are absent. . . . The icon painter has an entirely other relation to the flat surface than the one, for example, that Egyptian painting or Greek vase painting had. . . . The icon painter thinks in four dimensions and constructs a conception of spherical space, with the two-dimensional flat surface as his basis.”

The Place of Icons in the Transition from the Nineteenth to Twentieth Century

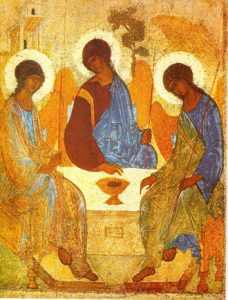

The debate that began in post-Soviet Russia bears on the way in which icons are to be presented and considered today. Starting from the evident facts that icons are not works of art like other ones and that their full meaning resides only in an ecclesiastical polyphony-symphony, some Orthodox believers would like to see the most venerated images that had been removed by force be returned to the churches. Today, the Mother of God of Vladimir (12th century) is placed in a church adjacent to the Tretyakov National Gallery in Moscow, and one can see people come into this same museum to pray in silence before Andrei Rublev’s Old Testament Trinity (early 15th century).

Andrei Rublev. Old Testament Trinity (Moscow, early 15th century).

The monk Grégoire Krug, an iconographer who died in France in 1969, stated that the presence of icons in the secular world has a meaning: “It is in this way that icons that are prayed to, those whose purpose is to serve prayer, complete their salvational action in the world. They can leave the church, be found in a museum or in the homes of collectors, and be part of exhibitions. Such apparently incongruous conditions are neither fortuitous nor absurd.”

In fact, throughout the twentieth century Russian icons have catalyzed the at-once utopian and prophetic movement of metamorphosis and transfiguration of painting in general, as well as of life as a whole, toward what Bruno Duborgel calls, in opposition to the “iconoclasm of a surfeit of naturalistic images and in rupture with it,” “the iconophilic obsession with approaching an experience of the Unfigurable.”

Bibliographical Hints

Boespflug, François, and Nicolas Lossky, Nicée II (787-1987). Douze siècles d’images religieuses. Paris: Cerf, 1987.

Duborgel, Bruno. Malévitch. La question de l’icône. Saint-Étienne: Université de Saint-Étienne, 1997.

Florensky, Pavel. La perspective inversée/L’iconostase et autres écrits sur l’art. Trans. Françoise Lhoest. Lausanne: L’Âge d’homme, 1992.

Larchet, Jean-Claude. L’iconographe et l’artiste. Paris: Cerf, 2008.

Nicéphore. Discours contre les iconoclastes, Trans. and intro. Marie-José Mondzain-Baudinet. Paris: Klincksieck, 1989.

Ouspensky, Leonid. Theology of the Icon. Trans. Anthony Gythiel with selections translated by Elizabeth Meyendorff. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1992.

_____, and Vladimir Lossky. The Meaning of Icons. Trans. G. E. H. Palmer and E. Kadloubovsky. 2nd ed. Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1982.

Sendler, Egon. The Icon, Image of the Invisible: Elements of Theology, Aesthetics, and Technique. Trans. Steven Bigham. Redondo Beach, CA: Oakwood Publications, 1988.

Troubetzkoï, Eugène. Trois études sur l’icône. Paris: YMCA-Press/O.E.I.L., 1986.

Yon, Ephrem, and Philippe Sers. Les Saintes Icônes. Une nouvelle interprétation. Paris: P. Sers, 1990.

Zibawi, Mahmoud. Eastern Christian Worlds. Preface Olivier Clément. Trans. from French Madeleine Beaumont. English translation edited by Nancy McDarby. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1995.

_____. The Icon: Its Meaning and History. Pref. Oliver Clément. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1993.

Jean-Claude Marcadé PhD, is a director of research emeritus at the French National Center of Scientific Research (Institute for the Aesthetics of Arts and Technologies). Author of Malévitch (Paris: Casterman, 1990), L’avant-garde russe 1907-1927 (Paris: Flammarion, 1995; 2007), Calder (Paris: Flammarion, 1996), and Nicolas de Staël. Dessins et peintures (Paris: Hazan, 2008), he is the president of the “Friends of Antoine Pevsner” association.