“Our way of life resembles a fair,” wrote the Stoic Epictetus. “The flocks and herds are passing along to be sold, and the greater part of the crowd to buy and sell. But there are some few who come only to look at the fair, to inquire how and why it is being held, upon what authority and with what object” (Epictetus, The Golden Sayings of Epictetus, translated and arranged by Hastings Crossley [New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company, 1909-14]: LXVIII). Recounting the fair before departing is also the role of the art historian who looks into the market. Indeed, this year our seminars will be devoted in large part to economics while events are already relegating to the past a number of the methods connected with the growing financialization of the world of art.

We begin with Elizabeth Lebovici and Caroline Bourgeois’s exhibition about money. For, it allows us to enter into the subject through works of art themselves. For the past three decades, art works have in large part been occulted by the emphasis placed on their financial value, while the general euphoria has increased tenfold the likelihood of their being forgotten in favor of the “market,” which had ended up being viewed as running the show. Tobias Meyer, Sotheby’s worldwide head of contemporary art and auctioneer, is said to have declared that “the best art is the most expensive, because the market is so smart”.

(http://artforum.com/diary/id=10968).

The quality of Lebovici and Bourgeois’s offering at Le Plateau, which was carried out with the limited resources at hand, opened onto some essential questions. For, it showed the extent to which artists have been working on the issue of economic links, going so far as to establish their own businesses.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of October 9th 2008

Money at the Plateau

Elisabeth Lebovici

Caroline Bourgeois

At the time we delivered our joint lecture on October 9, 2008, at the Arts and Societies Seminar, the situation was manifestly no longer what it had been three months earlier, on June 15, 2008, when the Argent (Money) exhibition opened at the Île de France/Le Plateau FRAC (Fonds régional d’art contemporain, the Regional Contemporary-Art Fund of Île de France/Le Plateau).

In a few days in September, the Lehman Brothers Bank asked for and obtained bankruptcy protection. The American Insurance Group (AIG) was saved at the last minute by the Federal Reserve. And such financial giants as Merrill Lynch and the Halifax Bank of Scotland had to be sold to competitors. Commentators have begun to compare the present economic situation to the Great Depression of 1929. The American financial crisis spread like wildfire to European banks and markets and then worldwide, and now a recession seems inevitable.

The basic features of the American financial crisis are well known: ill-advised loans to uncreditworthy households seeking to buy homes, securitization and expansion throughout the economy of the riskiest loans, downturn of the American real-estate market and snowball effect of a lack of confidence among financial agents, drying up of interbank loans and of credit within the economy. Could these mechanisms have been foreseen? Does this crisis point to the failure of monetary policies since the 1980s and, in particular, to the failure of the “new consensus,” which had been raised to the rank of an intellectual foundation for the modern central banks?

It is not uninteresting, within this context, to take an interest in art values. Indeed, some correlations have sometimes been observed between art prices and real-estate prices in large cities, for example. A number of writers have laid stress, the past few years, on the significance of “hedge funds” in the purchase and rapid resale of contemporary art. Especially contemporary art. For, it is in this area that prices climbed 132 percent between July 1, 1991 and July 1, 1992, or five times higher than what was observed in the other sectors of the market, like old and modern paintings.

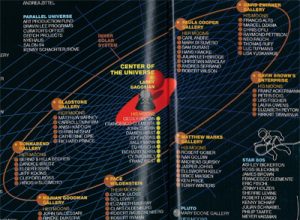

One could also observe that the world art market was up sharply in 2007 (according to the annual report of world markets, Cyclope). Sales on the auction market, estimated at $15 billion, are said to have increased last year, on a like-for-like basis, by 37% over 2006. It is in China (now accounting, according to some estimations, for 20% of the world market in contemporary art) and among Russian oligarchs, certainly, that one should seek the causes for these rising figures; indeed, sales of Asian art, usually organized in London and New York, have been expanded by sales in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai. Next, one must reckon with Chinese artists, who have exploded, en masse, upon the chart of records: three of them figure in the “2007 Top Ten” and ten have sold works for above one-million dollars.

What does the art market hold for us now? Can one think it will remain isolated and retain its autonomy? Can the new markets of China and Russia compensate for the retreat of Western buyers, when Asian stock markets are now in turn in the process of falling off? It is common knowledge that the correlation between financial markets and the art market is not direct and that the latter takes a little more than a year to react; the first bad figures would therefore be only an initial reaction to the subprime crisis of last year, according to The Art Newspaper.

In any case, on September 15–Black Monday for world finance–the British artist Damien Hirst collected 89 million euros. In two days, the auction, organized by Sotheby’s in London, of 223 of the British artist’s recent works brought in 139.2 million euros–a record for a sale devoted to a single artist, and far ahead of Picasso.

Looked upon by the artist as a mini-retrospective, this exceptional sale had the additional peculiarity that it afforded itself the luxury of being a “statement” event. Indeed, the auction grouped together works that had never before been exhibited, ones taken directly from the studio, from the artist’s factory, without going through a middleman. That constituted a first for this famous auction house, which had never, since its establishment in 1744, offered a direct sale from an artist. For the artist, it was “all profit”! By not passing by way of an art gallery, Hirst supposedly “saved” 40-50% on commissions as he received nearly all the profits from the sale. Some critics have mentioned the risk that, by offering so many works in one shot, he might lower his quoted value: but Hirst clinched a new record with the star attraction of the sale, The Golden Calf, which was carried away for 12.9 million euros.

Greeted in the art world as a provocation and a scandal, the “Hirst sale” can be analyzed in another way, and first of all as the continuation of a series of artistic projects that have been aimed at questioning or mimicking economic phenomena. Indeed, it may be analyzed as a continuation of the “covering up” of the field of aesthetics by the field of political economy, a project that might perhaps define, as well as other ones, postmodern art.

One must first note one very simple thing: among the cultural forms of expression (one can think here of music, theater, dance, and even literature), the visual arts are very much a domain in which money is visible, if not shown–and not only in the ostentation of a Marie-Antoinette at the Chateau de Versailles. Money has often been problematized in and through works of art. Since the origins of Western painting, coin, along with the direct or indirect relationship with the payer, has been given figural form, weighed, even represented (by the choice of one color rather than another, in terms of its cost, etc.). Artists have scrutinized crowns and wondered about the various organs of the art market. Money is not just an iconography, and some other artists have proposed an alternative economic circuit or have turned themselves into economic researchers, setting art up as a laboratory. These past few years, the indexation of art prices upon prices of luxury goods and the increasingly conspicuous influence of the private sector (collectors, trustees, patrons, etc.) on public or official arts events have undoubtedly transformed in a lasting way the “dealer-critic system” set in place at the end of the nineteenth century, to go along with the new aesthetic, an alternative to official taste. The result is that the media have practically stopped producing any evaluative discourse on art works that does not take into account the market’s own evaluation or the marketing terminologies of public relations.

We undoubtedly need to go back just a little bit in time, to nearly three years ago and the Miami art fair (a satellite of the one in Bâle) from which one of us returned simply stunned by the overwhelming power of the event, where what is literally a “fair city” dedicated almost entirely to speculation on contemporary art, or at least the staging thereof, took place. Few events (“La Couleur de l’Argent” [The color of money] at Paris’s Postal Museum) had been devoted to this theme. Whence the idea of an exhibition, L’Argent (Money), undertaken by the two of us for and with Le Plateau, an arts center operated with public funds in Paris’s nineteenth arrondissement.

For us, it was a matter of not being superfluous and therefore of distancing ourselves from an exhibition “on the art market,” like artists who “do” the market (Koons, Hirst, Murakami, Cai Guoqiang, Zheng Fanshi, Liu Xiaodong, etc.). We nixed that scenario straight off. Thus, in L’Argent just one video dealt with quoted values and investment in the art market–a “trailer” produced for the Arte televison network whose definitive version has yet to be completed.

Our first task was to inform ourselves face-to-face about the ways in which artists “talk” about money–with their works, that is, and not in their own lives. And we therefore had to ask artists first how they broach these questions within their work. This research materialized in an exhibition that occurred in two, or rather three, times and places: the time and place of compiling, archiving, and reading a vast amount of documentary material we had brought together about works from the past or ones so far removed geographically that they could not be lent to an institution and a space like Le Plateau; the hanging of lent works, most often ones from Paris or ones that could easily be obtained from elsewhere; and, finally, during the period of the public exhibition, a number of performances (by Annette Messager, Tania Bruguera, Cesare Pietroiusti), of moments of encounter (with critics, with the Société Réaliste, with the website Poptronics and Internet artists, with the shareholders of Ouest-Lumière, with the Paris Biennale and its association of supporters), filmed interviews, and especially new and spontaneous contributions from artists whom we did not yet know and who came to enrich the show.

An exhibition is necessarily made from decisions and from a subjective selection and hanging of works, the responsibility for which we accept. Two considerations serve to attenuate this general statement. First, money–the subject of our exhibition–is obviously an involved party in this exhibition, as with any exhibition. Nowadays, discussion of the budget for an exhibition concerns less the artistic choices than the transportation costs and insurance estimates (we have been able to observe that, during the show, certain exhibited works saw their insurance estimates increase exponentially, in keeping with the “new market prices” for artists following the Bâle fair). So, an exhibition on money is also, under the conditions we accepted, an exhibition with little money–not even enough to allow publication of a catalogue. A second remark is in order here: we tried to incorporate into this exhibition proposals that to us seemed “major” or “interesting,” precisely ones that called back into question our own aesthetic presuppositions for evaluation and judgment. Finally, we chose, voluntarily or involuntarily, to show “materialized” works or proposals more than dematerialized efforts–in accordance here, no doubt, with the logic of an already established program involving the institution and its pedagogical mission. We asked Annick Rivoire and her Poptronics website to carefully untangle the question of the Internet economy and of the possible tie-ins artists’ projects construct there–with the hope that other exhibitions, different ones, might be constructed elsewhere and otherwise.

Our presentation includes a few images that we did not exhibit.

1. Introduction

The composer-musician Serge Gainsbourg burned a 500-franc note as a token of his artistic celebrity. Such celebrity is decidedly based upon spending–a notion dear to Georges Bataille that gave rise to a lovely exhibition at the Pompidou Center in 1979, back when Pontus Hulten was the director of the museum. That exhibition, curated by Jürgen Harten and Horst Kurnitzky, was entitled: Musée des sacrifices, Musée de l’argent (Museum of sacrifices, museum of money). Money paints; it is a subject that goes beyond the question of modernism.

Quentin Metsys. The scene is painted. Leaning on a green felt table, the color of gambling tables, and seated before a background obstructed by bare shelves, a male character and a female character appear side by side. Their faces incline forward, looking at what the man is doing. With lowered eyelids, the man, concentrating fully on what he is doing, weighs money with a skillful hand. He could do it with his eyes closed. That is his trade. Money changer? Lender? Usurer? The era in which this canvas (The Moneylender and his Wife, 1514, Louvre Museum, Paris) by the Flemish artist Quentin Metsys was painted belongs to a pivotal period in the history of Western Christianity, when the money trades appeared along with men who live off the proceeds made from money without themselves being producers of wealth.

He acts and she looks. Leaning over, her eyes trained on what he is handling, the female character, both of her hands placed on a book of hours, flips through images related to contemplation without actually seeing them. A mirror in the foreground reflects the presence of a third person, the indication of a no doubt attentive countenance. He integrates the point of view of the spectator. He puts us in our place. We are good clients.

Edouard Manet. Commerce is part and parcel of artistic work and sometimes rises back up to the work’s surface. Because the sum paid by the patron, Charles Ephrussi, exceeded the price asked for his painting Bunch of Asparagus (1880), Manet made for him, in addition, Asparagus (1880), a single one, “since one in your bunch was missing.” The buyer did indeed get his money’s worth: Manet exhibited here two distinct visual projects, two for the price of one: a picture plus a “picture of the picture” (as Éric Alliez has said) nakedly exposing the previous one and casting light on the context, the size, and the orientation of the vegetable, as well as its pictorial physicality. The solitary asparagus, like a pale corpse, “without any artifice in its presentation, which even still in Chardin gave it class and distinction” (as Thierry de Duve has said) is, thus, the foreign element that de-idealizes the exchange.

Hans Haacke. While Asparagus ended up in the Orsay Museum, Bunch of Asparagus went into the Wallraf-Richartz Museum collection in Cologne. Invited in 1974 to commemorate the centennial of this museum, Haacke designed a series of panels. The first one is a reproduction of Manet’s painting. Each of the ten others presents the people who bought the picture after its completion by the painter, along with the price they payed to acquire it. The description of the social and economic status of those who possessed this painting is a contemporary-art project. The museum director turned this project down. Haacke’s exhibition finally took place at the Paul Maenz Gallery of Cologne.

In 1986, at the Consortium in Dijon, Haacke presented Les Must de Rembrandt, a monument that explains the relationships between the Rembrandt Trust (the largest Afrikaner business group under Apartheid), the Richemont financial group, and Cartier Monde–which owns Cartier’s Must (“must-haves”) line. Photos of black workers in gold mines and coal mines, whose attempts at an uprising had been violently repressed, were framed by the inscription in gold letters of the names of all Rembrandt companies in South Africa. Later, in a famous dialogue, the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and Hans Haacke endeavored to offer an update on the power changes that had taken place in the world of art since the 1980s. That was a time when the idealization of companies and of the business world was represented, in the manufacture of aesthetic value, through the intervention of financial groups as a way of offering a form of symbolic domination over exhibition policy.

Marcel Duchamp. In 1919, he signed a fictitious, handmade check he gave to Dr. Daniel Tzanck, the then-president of the French Society of Art Collectors, in payment for the dental work done on the artist. The bank Duchamp created from which to draw a check was called “The Teeth’s Loan & Trust Company, Consolidated,” headquartered on Wall Street. Duchamp reported that he bought back his check from the dentist at a much higher price than the sum written on it. During the same period this check was fabricated, Duchamp captured 50 cubic centimeters of Air de Paris in order to bring it to the American collector Walter Conrad Arensberg.

In 1925, Duchamp found a way of imagining the means to play at the Monaco Casino without financial worry. To build up the capital, it sufficed, he thought, to float 500-franc bonds at 20 percent interest (see the bond, opposite). Thirty bonds were printed showing the image of a larger-than-life Duchamp in the style of a little devil with outsized ears, the face covered in shaving cream. His portrait is to be found on the roulette wheel, a composition made by his friend Man Ray. Each note bears Duchamp’s signature and that of “Rrose Sélavy.” Alas, the artist’s effort was not crowned with success. Only two bonds were to be sold, though those ones to members of high society: Jacques Doucet and Marie Laurencin.

Yves Klein. Klein consumed the consumption of Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility, the “ritual” rules of whose transfer Klein was to set in 1958. Each zone was worth a certain weight in gold. Yet authentic immateriality (immortality?) has no price–unless, that is, the buyer would burn his certificate and throw half of the weight of gold in a river in the presence of a museum director, a well-known art dealer, or a critic and two witnesses. At the moment the buyer thinks that he has acquired his coin of pictorial immateriality, he obtains but ashes.

Joseph Beuys. To the prospect of the cacophonous mythologies of Beuys, who seemed to have taken on all the roles, the art historian Thierry de Duve responded with a unique figure for designating this creative artist, that of “the artist as proletarian.” This in no way implies his ideological alignment around certain class positions, but rather “a faculty for producing value that, in order to be authentic, has to be unique to the artist.” Now, what Beuys promises is the universalization of this faculty, this labor power, through a malleable system of generalized “creativity.” “Kunst = Kapital,” Art equals Kapital, the capital of coming social change. Utopia and reality. Located now in the Hallen für Neue Kunst of Schaffhausen (Switzerland), Beuys’s piece Das Kapital Raum 1970-1977, originally done for the Venice Biennale in 1980, can be seen as the condensation of thought-spaces and object-spaces that were already being produced starting in 1970.

Andy Warhol. In English, “I buy it” means not only “I am purchasing” something but also “I believe it,” I am in agreement, I subscribe thereto, I sign off on it. That’s it! “I sign.” Art implies a tacit or overt commerce between production and looking. In 1975, in The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again), Warhol stated, “Business art is the step that comes after Art. I started as a commercial artist, and I want to finish as a business artist. . . . Making money is art, and working is art and good business is the best art.”

There is no point in becoming indignant, Warhol seemed to be saying. However little one might subscribe thereto, one must admit that his work sets the torch to any vague attempts at differentiating the “disinterested” collector from the consumer, nay even from the speculator. Warhol wanted to be a machine; he was the “cash register of art” (Thierry de Duve), of all media likely to become art, whether it be painting, cinema, television, the print media, or any sort of hide or film. Exhibiting the dollar, a car accident, an electric chair, or the most “wanted” men (manhunt = sexual desire)–all these were for him (but also for us) equivalent subjects of the same value.

Marcel Broodthaers and the bankruptcy of the museum. Take the invitation card for Broodthaers’s first show in 1964: “I, too, wondered whether I could not sell something and succeed in life. . . . Finally the idea of inventing something insincere finally crossed my mind.” This “something insincere” is indicative of Broodthaers’s ongoing reflection on the constant in the work of art: “I mean the transformation of Art into merchandise,” when all the utopian potentials of modernist beliefs have been exhausted. Take the art object in the era of the culture industry. This is what he is articulating, straight off, without establishing a hierarchy among productions, reproductions, commentaries, catalogues, films, sets, and exhibitions. “Art as the Art of Selling” was the subtitle of his 1972 show at the MTL Gallery in Antwerp.

In 1968, Broodthaers opened a museum at his home: the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles (Nineteenth-Century Section), making reference to the mythical authority of the eagle as well as to its notorious stupidity. Broodthaers inscribed the name of the museum on his windows and stocked his apartment with works’ shipping crates, hermetic sarcophagi displaying only the names and indications of their place of destination. These crates gave figural form to the visual arts while signifying the disappearance of the work in museum presentations. The invention of an empty institutional identity producing a program, many and varied papers, and so on, is a critical way of looking at official exhibition sites, their storage practices, and how they legitimate art. The staging of the museumification of the visual arts was continued through the opening of various Sections–including the Financial Section in 1971–until the institution closed for reasons of bankruptcy in 1972. For its creator, art could survive only so long as it admitted its subordination to the dominant values: ideology and speculation. The final stage was to occur when the museum, which had itself become a commodity, was put up for sale: what remains is the art of the production of production.

2. Here is where our exhibition began. We thought that we had too many works, and that turned out not to be the case. The spatial articulation of the hanging of the show allowed several configurations and their interactions to be distinguished.

Presented near the entrance to the exhibition was a sign by Claude Rutault that had been hung on the balcony of the Parisian office of Ghislain Mollet-Viéville beginning in September 1996. Rutault made the collector responsible for literally pro-ducing his work by painting it the same color as the wall for which it was destined. In this way, the “production of production” confers upon the work, as it is exhibited, a paradoxical temporality. This is summed up here in the form of a “For Rent” type of sign.

A. Entrance and First Room: Questions of Gender and of Authorial Rights.

To us, it seemed appropriate to open the festivities with works that immediately integrate the question of the artists’ bodies, of the bodies of those viewing their installations . . . and of the bodies of the organizers, too.

Matthieu Laurette. The inscription “Let’s make lots of money” is a proposal from the artist to be implemented by the exhibition’s organizers, to whom were left the “manner” and the placement of the text’s inscription.

Orlan. Questions of gender, sex, and sexuality also weighed on the alleged universalism of the exhibition arrangements–and, therefore, on the productions that subvert the exhibition’s economy and its very subjects. At the 1977 Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain (FIAC; International Contemporary-Art Fair), Orlan, seated behind the image of a nude bust set on stage, invited people for Le Baiser de l’artiste (The artist’s kiss), promising a kiss to every person who inserted five francs into a specially built slot set between the two breasts. The coin slid down the plastic esophagus and then suddenly fell to the bottom of a transparent pubis-drawer. At that moment, the client received his or her kiss. Here, Orlan lent her support to a visual, auditory, and odoriferous reconstitution of this action. One thinks also of the offerings of Annette Messager, which make of the everyday their raw material, thereby ceaselessly parodying the sexual differences supposedly also at work in a visual economy.

Joanna Vasconselos chose to install, in situ, an installation of metal poles connected by ropes that set up a waiting line, a way of directing the bodies of visitors as if they were, for example, in a bank. The ropes were made of (fake) hair of many colors. This was an unexpected incursion of an extension of the body, one tied to female seduction (cf. the hair of Mélisande), that replays on this stage of money the ongoing concerns of these artists from Portugal: the female body as money (Une direction, 2003).

Bertrand Lavier (Golden Brot, 1983). We would have loved to have, of course, the much-talked-about Brandt/Fichet Bauche, a refrigerator set atop a safe. The thing proving too heavy for the exhibition space, what he really wanted was one of his vitrines (display cabinets for a collection) to be filled with a number of fetish objects dealing with the issue of the “monetarization” of art: Wim Delvoye’s “Action Doll” tie-in, Shu Lea Chang’s Monnaie d’ail (Garlic money), a copy of Jessica Diamond’s “Do It” project, Sol LeWitt, and Lawrence Weiner. In 1971, Seth Siegelaub gave up playing the role of a conceptual-art exhibition organizer in order to take the time to prepare “The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sales Agreement,” in which it was proposed that the artist receive 15 percent of the profits garnered from each of the transactions concerning his works. Money as “the sinews of war”: the supposed purity of the art work is thus haunted, infuriated nonstop, by the questions of life and survival. The personal is political in matters of art and money, too.

B. In the second room, after passing by a poster by Arnaud Labelle-Rojoux, we had productions, whether collective or not, of works from the 1980s, of a new social relation to businesses, and of the rethinking of the traditional role of artists opposite or against corporate communications, including within the culture industries.

Thus we had Ouest-Lumière, which was an electrical generator bought by Yann Toma before becoming a joint-stock company whose goal is to “produce and distribute Artistic Energy for the next hundred years.” Among the numerous artistic firms that spurn the individual identity of the modern artist and choose instead to label their products under the heading of “design,” there was also Information, Fiction, Publicité (IFP; Information, fiction, advertising). In a lighted box with the group’s logo on it appears the transaction performed to buy the work, the check for which is at once the indication, the icon, and the referent (Société Générale, 1984). General Idea’s “copyright paintings” (1987), on jeans or with a gilded logo, are part of the same effort at enunciation and denunciation mixed together.

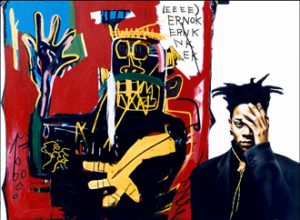

Répétition Générale (General rehearsal). We may ask whether in the 1980s, during the boom in the Western markets that lasted until 1989, the implementation of new advertising, promotional, and media practices designed to give visibility to artistic “trends,” the increase in the number of large exhibitions, and the industrialization of culture, including that of artistic products, were accompanied by a change in the status of the artist. Philippe Cazal, for example, exposed the figure of “the artist in his environment,” surrounded by champagne, cocaine, and pretty girls, everything fitted out with price tags. “The Artist”: a fashionable profession? La Magie du Succès (The magic of success, 1986) is a form of staging that was already nostalgic before being recognized as such.

Sensitive to the way in which the media have transformed art into cliches and the figure of the artist into a buffoon, Ernest T., under this elusive pseudonym (the T as modernist emblem of orthogonality, the right angle), produced canvases as banners that allowed him to ridicule this other self of his with impunity and to make that self into the object of a strategy that denounces at the same time that it enunciates the meanness of the art market. As an artist, Gilles Mahé is one of the inventors of “free” or “gratuitous” art. He makes visible those who pay for this free or gratuitous art, the advertisers manufacturing the very material of its publication. Through gratuitousness, art given away for free, one makes manifest the shift toward the advertiser that is being carried out by all media–magazines as well as television and today the internet–though this economic model for the Web is today being brought back into question.

At MaMCO in Geneva something described as stocking was installed (and sometimes shown). It is that of the agency known as Readymades Belong to Everyone®, which opened in New York in 1987 and closed in 1993. “I am part of a fiction for producing something that truly fits into reality,” the agency says. Created by Philippe Thomas, this agency proposes that “characters”–a deliberately ambiguous term–enter into art history through his library–his catalogues, his lists, and his registers. In short, he proposes the archiving of the work, before it comes into existence, as the real stake in the transaction. The agency’s “clients” then pay for their signature and, with it, the entrance fee into a small theater where collectors, curators, critics, art historians and journalists take on figural form. This small theater does not appear as such but rather in the bureaucratic image of the managing company and of its images, all the fictional consequences of which Thomas has imagined.

This company did not limit itself, however, to producing works whose singularity derives from the fact that their first sale is accompanied by the attribution of their signature to the buyer–a procedure inspired by the one quite commonly used in literary fiction and which, in the case of the novelist, consists in attributing remarks, thoughts, or even entire works to characters. As an inevitable development of the internal logic of this agency’s work, it passed in 1991 from attributing a single work to giving attribution to an entire exhibition. The quotation of the title of a book by Nabokov, Pale Fire, at the Centre d’arts plastiques contemporains (CAPC, Center of Contemporary Visual Arts) of Bordeaux, afforded a re-envisioning of the entire history of the Western museum and went so far as to associate it with various works of unknown artists (clients of the agency) which are hung on the walls with the blessing of the institution that signs the show. As Patricia Falguières has pointed out, it is a matter not of a physical retreat, but of a genuine re-investiture, of the exhibition. This is an exhibition in which the verbal and the visual, the book and the site would no longer be opposed to one another. In this way the stock, the stocking, the archiving, the planning boards, and the postcards ultimately become the Cabinet d’Amateur (collector’s gallery) of the aesthetics of production.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres makes his way through similar problems: not only do his “stacks” and his mounds of candy merge the one with the many, the autographical character of the work of art with the allographic character of the book and of the musical work, but, in addition, it is up to the buyer to invest for them to be produced. The personal is political: with his paintings representing the graphics of the current state and progressive decrease in T4 cells (displaying in this way the decline in the artist’s vital functions), Gonzalez-Torres invites us to meditate on a sort of speculation that affects not only works but also the life and death of artists.

In December 1979, “The Miss General Idea Boutique” opened at the Carmen Lamana Gallery in Toronto. The show was at once a sculpture and a sales counter, a feature that signals quite well the dual function of work and product. The boutique, qua “artwork and artshop,” anticipates the development of the “museum shop” while being installed within a gallery, then, later, within a museum exhibition space–which is justified, let it be said in passing, only in its separation from the sales shop: by transforming the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris into a Hybermarché (Hybermarket), Fabrice Hyber was likewise to foist this same sort of structural perversion. In its subsequent presentations, the shop becomes by turns a “work,” closed to sales and simply visitable, and a “shop,” open for buying, depending on the day, the place, and so on. Other versions also exist, such as General Idea’s ¥en Boutique (1989), which we presented at Le Plateau. The gallery or museum space thus promotes merchandise General Idea has produced, inspired by the fact that marketing of a product exists before the production process and the production line start up–with such “preventive appearances” as market research, fashion shows, and television casting calls.

C. Second Room: “Bling Bling” and Dematerilized Money.

A statement by Philippe Cazal, “Art doesn’t give credit,” is set before some photos by Marylène Negro that make reference to an action performed several times during the exhibition and that consisted in leaving a Cadeau (Gift)–the schematic drawing of a gift-wrapped package–on the windshields of cars in the neighborhood where Le Plateau is located.

With the “cash machine” painting by Claire Fontaine–a very young artist who “makes use of her fresh and youthful appearance to transform herself into an ordinary, everyday individual and into an existential terrorist in search of emancipation”–and the perpetual and unending investigation undertaken by Sophie Calle (with Fabio Balducci), representations centered around the dematerialization of money were expounded. Olga Kisseleva and her Troll mirror with a dollar sign invited us to look into the mythologies of money under Communism. Michel François makes a mass of pastry boxes into a pile of gold like Scrooge McDuck’s.

Thomas Hirschhorn, with his terrorist realism, has manufactured a huge Swiss watch out of cardboard. Sylvie Fleury has reproduced, unchanged but in heavy marble, a Chanel shopping bag. Matthieu Laurette has offered, here again, one of his conceptual propositions: a graph representing the euro/dollar exchange rate over the year preceding the inauguration of the exhibition.

D. Third Room: Money Materialized, Scrutinized, and Displayed. The “Doc” and its Photocopier.

Plying money to show its color, its odor, its hallucinatory effects. With her blister-packed pills, which promise all sorts of transformations, all kinds of changes “instantaneously,” and which she sells in museum shops all over, Dana Wyse has set up a parallel economy in galleries and on the market for rarities.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall and the stock-market crash, Moyra Davey closely examined with her camera at the end of the 1980s and in the early 1990s the surface of one-cent coins, the humblest money emitted by the American Treasury, as well as bills. Cildo Meireles put bills “out of circulation.” Zoe Leonard displayed one-hundred one-dollar bills she found, each one provided with inscriptions. A very large number of bills presented, photographed, represented, certificates or other traces of stock shares, such as that of the Mur de l’Argent (Money wall), and bleeding bills by Michel Journiac populated this room of works by Adel Abdessemed, Antoni Muntadas, Claude Closky, Ernest T, Malachi Farrell, Et n’est-ce* & / etc., Dana Wyse, Kris Martin, Cildo Meireles, Moyra Davey, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Gabriel Orozco, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin, Sigmar Polke, Zoe Leonard, David Hammons, Cady Noland, Josephine Pryde, Fabien Hommet, and so on.

E. Passageway: Two Generations, Two Business Firms

From the work of Iain Baxter&–who, in the name of his company N.E. Thing, organized a game of monopoly with real money in a bank in 1973–we have also exhibited some landscape paintings borrowed from Canadian bank notes, where he confined himself to hiding the numbers with a picture mount (1969).

Société Réaliste, a group of “political designers,” has commented: “Physical money is the systematic meeting point between politics and economics: there is no commercial exchange without liquid assets, no State without issuance of its own money.” Their work Marka (2008) has three components: a sculpture in metal, representing a 10X enlargement of a one-euro coin, with the grooves on the object’s edge removed in order that one might read the names of the countries forming the perimeter of the European fortress; a political world map, retrieved from CIA databases, that appears superimposed on the Europe in the numismatic design which constitutes the heads side of the one-euro coin; and a series of vinyl stickers that remind us of the derivations of marka in French: “a sign marking a boundary,” marka yields marche (step) marcher (walking), marge (margin), mark, marquer (marking), marque (brand), marquis, and so on.

F. Fourth articulation: Figured, Disfigured; Money and the Image’s Means

Juxtaposed to the euro painted and dripped in Larry River’s style by Rena Spaulings, a collective artist and dealer, are the Gloria Friedmann carpet representing a currency-exchange room and a videogram in which cows, painted with the symbols of stock-market indexes, are surrounded by folk dancers, not far from the video of a performance by Cesare Pietroiusti and Paul Griffiths that combines ingestion, digestion, and excretion, a cycle in which money always come out white, as if laundered. L’Argent (Money), Suzanne Lafont’s photographic polyptych full of pictorial and cinematographic references, offers a counterpoint to these icons.

Finally, Louise Lawler, with two images of paintings hung in rooms of auction houses, shows the loss of autonomy of the art work, which no longer appears nor is apprehended any longer, even visually, outside of the economic context of an exhibition.

While the world of art is magnetically drawn to globalized capitalism, while arts events are indissolubly connected with the promotion of tourism, shopping, real estate, and speculation, and while one must bow to these globalizing trends, these things undoubtedly do not occur without one having a word to say about them. For, artists have a lot to teach us and have taught us a lot during these past few months in the company of their works–if only to comment upon this exhibition on money and the way it was organized. This exhibition was the fruit of a confrontation among works and with the curators that has allowed some significant articulations to be sketched out. The social transformations that occurred during the 1980s, before the fall of the Wall, became more vivid to us. This was back at a time when the status of the author was being turned upside down and that of businesses (including cultural ones) was glorified. The AIDS epidemic is indissolubly linked to this moment of oscillation between public and private, when the “I” of utterance, of illness, and of exclusion was inscribed upon the (anonymous) Wall of money and capitalization.

The period after the fall of the Wall, with its excess of consumption (including that of images), seemed to us to coincide, both spatially and chronologically, with the dematerialization of money. The question of the relations between money and power seemed to us to give way to worries centered around the relations between money and (national, cultural, sexual) identity–worries that continue to this day. Finally, the play of figuration and disfigurement and the presence of bodies also appeared to us to have a nonnegligible place in these productions. Thus, when it gives rise to artistic work, even the immateriality of the stock-exchange trade and of foreign exchanges (which have also become dematerialized) finds itself enmeshed in a production line or manufacturing line that gives body to it. This is perhaps the major lesson to be taken away from this exhibition. Art gives body, even if this body is not exactly an organic one.

-

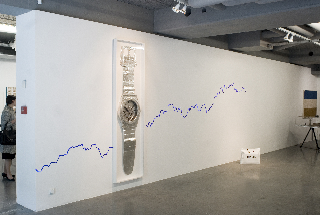

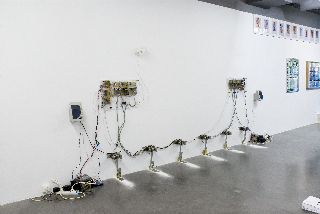

View of the exhibition.

Entrance to Le Plateau with, in the foreground, Joana Vasconcelos, Une direction, 2003.Stainless steel and artificial hair. Varying dimensions.

Courtesy of the artist and the Nathalie Obadia Gallery, Paris.

In the background, part of the 2007 reconstitution of Le Baiser de l’artiste (The artist’s kiss) by Orlan.

-

On the ground, Sylvie Fleury, Untitled, 2008. Bronze. 40 x 50 x 11 cm. Courtesy of the Almine Rech Gallery, Paris/Brussels.

On the wall: Matthieu Laurette, € vs $ (Euros versus Dollar), 2001-2008. Wall painting in progress (graphic representing the Euro/Dollar exchange rate for the year leading up to the day of completion). Varying dimensions. Unique work. Courtesy of the artist, the Blow de la Barra Gallery, and the Gaudel de Stampa Gallery, Paris.On the wall: Thomas Hirschhorn, Swiss Made, 1999. Cardboard, paper aluminum, felt, wood, plastic, and transparent film. 230 x 50 x 5 cm. Private collection, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

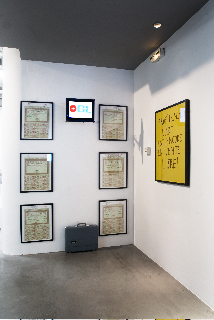

At right: Arnaud Labelle-Rojoux, Profitez-en . . . , 2005. Writing in acrylic paint on colored paper. 80 x 62 cm. Pierre Cornette de Saint-Cyr Collection, Paris.

Center: Ouest-Lumière, Stock Exchange, 2008. Mixed media. Varying dimensions. Courtesy of the Patricia Dorfmann Gallery and Art & Flux, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

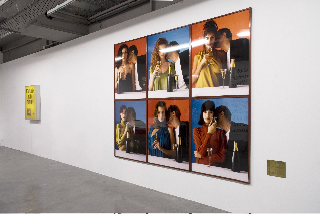

In the foreground: Philippe Cazal, La magie du succès (The magic of success), 1986. Six Cibachrome photographs. Each one: 100 x 80 cm. Engraved brass plaque. 17.5 x 18.5 cm. Daniel Bosser Collection, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

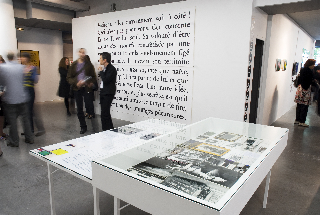

In the foreground: documentary display cases about the work of Gilles Mahé. Mahé Collection, Paris/Saint Briac, and private collection, Paris.

Photo: Martin Argyroglo

-

Readymade Belongs to Everyone®, 1993. Backstage–Le Plateau, Paris, 2008. Varying dimensions. MAMCO Collection, Geneva, Benoît d’Aubert Collection, Paris, Claire Burrus Philippe Thomas Estate.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

On the ground: Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Untitled (Himmler, Hate, Hole, Helms), 1990. Black and white offset printing on red paper. Pile of sheets of paper. 71 x 60 x 56.5 cm.

Fonds National d’Art Contemporain Collection/CNAP. Courtesy of Jennifer Flay, Paris.

On the wall: General Idea, Copyright Paintings, 1987. Courtesy of the Frédéric Giroux Gallery.Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

General Idea, Yen Boutique, 1989-1991. Installation: metal, painting, textiles, offset printing, silkscreen printing, ceramics, glass, brass, paper, enamel, plastic, nylon. 200 x 350 x 350 cm. Fonds National d’Art Contemporain Collection/CNAP.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

Left to right on the back wall: Sigmar Polke, Sans titre (Untitled), 1988. Banknote. 8.5 x 17 cm (20 x 39 cm with frame). Private collection, Paris.

Zoe Leonard, One Hundred Dollars, 2000-2008. 100 one-dollar bills, thumbtacks. Each one: 5.6 x 6.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the Yvon Lambert Gallery, Paris.David Hammons, Money, 1989. Fabric, plastic, gold paint, coins, paper. 121 cm. Private collection, Paris.

On the ground: Cady Noland, Eveready, 1992. Mixed media. 30 x 48 x 33 cm. Private collection, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

Malachi Farrell, Money Money, 2000. Installation. Mixed media. Nadia and Cyrille Candet Collection, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

-

Left: Reena Spaulings, Money Painting (50 Euros), 2005. Mixed media on canvas. 91 x 178 cm. Courtesy of the Chantal Crousel Gallery, Paris.

On the ground: Gloria Friedmann, Nous sommes les antiquités de demain (We are tomorrow’s antiques), 2003. Printed carpet. 433 x 350 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the serge le borgne Gallery, Paris.

On the wall: Gloria Friedmann, Tableau vivant: Money Makes the World Go Round, 2005. Digital print. 50 x 100 cm. Courtesy of the artist and the serge le borgne Gallery, Paris.

Photo : Martin Argyroglo

Bibliography

Artforum (special issue: “Art and its markets”), 46:6 (April 2008).

Benhamou, Françoise. L’Économie de la culture. Paris: La Découverte, 2006.

Benhamou, Judith. Art Business (2). Paris: Assouline, 2007.

Beuys, Joseph. Qu’est-ce que l’argent. Paris: Arche, 1997.

Claude Closky 8002-9891. Exhibition catalogue. Ivry: MAC/VAL, 2008.

General Idea. FILE Magazine. Ed. Beatrix Ruf. Zurich: JRP/Ringier, 2008.

Goux, Jean-Joseph. Frivolité de la valeur. Essai sur l’imaginaire du capitalisme. Paris: Blusson, 2000.

Huitorel, Jean-Marc. Art et économie. Paris: Cercle d’art, 2008.

Les Couleurs de l’Argent. Ed. Jean-Michel Ribettes. Catalogue. Paris: Musée de la Poste, 1991-1992.

Lawler, Louise. The Tremaine Pictures–1984-2007. Zurich: JRP/Ringier, 2008.

Lebovici, Elisabeth. With Mike Hunt, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Dana Wyse. How to Turn Your Addiction to Prescription Drugs into a Successful Art Career. Paris: Editions du Regard, 2007.

Massera, Jean-Charles. Amour, Gloire et CAC 40. Paris: P.O.L., 1999.

Moulier-Boutang, Yann. Le Capitalisme cognitif. La Nouvelle Grande Transformation. Paris: Éditions Amsterdam, 2007.

Moulin, Raymonde. Le Marché de l’art: Mondialisation et nouvelles technologies. Paris: Flammarion, Paris 2003.

Musée des sacrifices, Musée de l’argent. Ed. Jürgen Harten and Horst Kurnitzky. Catalogue. Paris: Centre Pompidou, 1979.

Naumann, Francis. Marcel Duchamp: L’Argent sans objet. Caen: Éditions de l’Echoppe, 2004.

Les ready made appartiennent à tout le monde. Exhibition catalogue of Philippe Thomas and his agency Readymades Belong to Everyone. Barcelona: MACBA, 2000.

Sagot-Duvauroux, Dominique, and Nathalie Moureau. Le Marché de l’art contemporain. Paris: La Découverte, 2006.

Siegel, Katy, and Paul Mattick. Money. New York: Thames and Hudson (Questions d’art collection), 2004.

Toma, Yann. Ouest-Lumière–La Collection. Dijon: Presses du réel, 2008.

Simmel, Georg. The Philosophy of Money. Ed. David Frisby. Trans. Tom Bottomore and David Frisby from a first draft by Kaethe Mengelberg. 3rd English ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Warhol, Andy. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (1975). Orlando: Harcourt, 2006.

Wu, Chin-Tao. Privatising Culture: Corporate Art Intervention since the 1980s. London: Verso, 2002.

Zola, Émile. Money (1891). Trans. Ernest A. Vizetelly. Phoenix Mill: Alan Sutton, 1991.

Elisabeth Lebovici is a historian and art critic. She has recently published, along with Catherine Gonnard, Femmes/artistes, Artistes/femmes, Paris de 1880 à nos jours (Éditions Hazan, 2007). Lebovici, who worked in the culture service of the Paris newspaper Libération between 1991 and 2006, currently co-directs the “Something You Should Know” seminar at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

Caroline Bourgeois is an exhibition curator. She was Artistic Director of Le Plateau from 2004 until 2008. Bourgeois previously worked as an independent curator and producer (Valie Export, Point of View, project on Line 14 of the Paris Métro system, etc.). She is today charged with the management and exhibition of the François Pinault Foundation’s video collection.