Brett Littman, who has worked in the alternative art world of downtown New York, retraces here the history of noninstitutional art forms and art exhibitions from the 1960s to the present. He helps us to gauge the power of art actions that were able to thrive only against a background of protests against capitalism in general and of anti-Vietnam War politics in particular. Not that these experiences would not have survived–some of them have, indeed, endured–but they have done so in a landscape now radically altered by new paradigms where economics has come to dominate all forms of social activity.

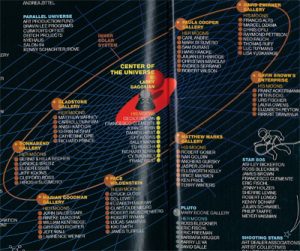

Georges Armaos, for his part, goes back over the “rules of the game” on the New York art market, whose overheating adds to its strange aura. He reviews the role each actor plays on an artistic stage that is directed more and more by dealers to the detriment of museums and critics.

In this landscape, what remains to be written is the international history of the means artists have always availed themselves of in order to escape their condition as pawns on the chessboard of consumerist societies. These, indeed, are societies that regularly prefer to take art as a commodity that is both magical and profitable.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of January 17th 2008

Alternative Arts Movement

in New York

A Personal Histort

Brett Littman

Over the past fifteen years I have worked in four different organizations that were founded in New York in 1976/1977. These organizations are all part of the history of the Alternative Arts movement in New York, were all founded in downtown New York, all received significant start up funding from the New York State Council on the Arts and were originated to address under-recognized art forms, artists, and anti-institutional curatorial practice (non-collecting) (P.S.1 and The Drawing Center) or a desire on the part of craft practitioners to free artistic production from the factories (UrbanGlass and Dieu Donne Papermill).

In this essay I will present a timeline of institutions and events between the late 1960’s to early 1970’s. The four major ideas that I will explore are:

1. Arts and Politics

2. Identity Politics

3. The Anti-Institutional Institutions

4. Studio Craft Movement

We will see from this timeline that the Alternative Arts Movement in New York was intricately linked to the political and aesthetic issues prevalent in the late 1960’s – mid 1970’s. Vacant real estate and a soft economy also played important roles in the development of these groups. During this time New York experienced one of its worst economic crises – leaving large swaths of the city undeveloped and empty buildings, schools, and warehouses were left vacant. At the time a handful of politicians and city planners were cognizant of the fact that culture could be a way to stimulate the economies of certain geographic locations. Through the auspices of the government arts agency called The New York State Council on the Arts and their leadership significant start up grants were given to these groups once they had assembled and gotten their non-profit status and governance in place. In addition, Borough Presidents (who today have little power) were able to turn over abandon city buildings, repurpose them for cultural use and make them CIG’s (Cultural Institution Groups) which were then added to the city’s line item budgets in perpetuity. This was an important step in helping these groups stabilize early on and has provided the basis for survival moving forward. Of course city funding has not keep apace with rising budgets and often when things are bad economically in New York the culture budgets are the first to be slashed which in turn means cutbacks of staff, hours and offerings at CIG’s.

I also want to highlight that many of these spaces were direct offshoots of political action groups protesting the war and policies at the major museums like MoMA, the MET, and the Whitney. Today there is still ongoing scrutiny of many of the issues raised by these groups including: the percentage of women and people of color represented in museum exhibitions and in permanent collections, how often these works are shown, what kind of position museums take in relation to sensitive racial and political topics. However, overall, there seems to be a more collegial relationship between organizations and even wholesale affiliations between old enemies (P.S.1 and MoMA).

Arts and Politics

The beginning of the Alternative Space Movement is very much tied to the social and political movements of the late 1960’s when artist, writers and other creative people began to mobilize in protest against the Vietnam War. This then turned into broader protests and actions in relationship to artists’ individual rights in institutional contexts. Among the important groups and actions that laid the groundwork for the Alternative Space Movement were: Artists and Writers Protest against the War in Vietnam (aka Artist Protest), 1965; Art Workers’ Coalition, 1969; Artists Poster Committee, 1969; Guerrilla Art Action Group, 1969; Art Strike, aka New York Artist Strike, aka Art Strike against Racism, War and Oppression, 1970; and Artists Meeting for Cultural Change, 1975.

The Art Worker’s Coalition (AWC) had the most far reaching impact on the development of Alternative Spaces in New York. AWC was started in response to the artist Takis removing his sculpture from MoMA because he did not want to be represented by the piece in the Machine exhibition they were organizing. The work was in MoMA’s collection so this created a problem and a question as to what rights artists had in relationship to their work being show once it was in a museum collection. A group of artists and then director of MoMA Bates Lowry meet to discuss their demands. AWC held a forum on April 10th 1969 at SVA and later redefined its demands to MoMA and all New York museums. They published the transcript of the “Open Hearing” at SVA and also produced Documents I which surveyed the groups activities up until 1971 when they officially disbanded. Some of the documents from the “Open Hearing” are available on the internet, are still quite relevant today and are very much worth reading. They can be found at http://www.journalofaestheticsandprotest.org/5/articles/forkert.htm.

Identity Politics

AWC mobilized activity around ethnic, gender, and sexual orientation in relationship to institutional exposure and professional inequities faced by people of color, women and the gay and lesbian community in the art world both in terms of exhibition possibilities, recognition in the canon and the issue of culturally underserved geographic areas in the city. Out of AWC several non-profit arts organizations were founded in the 1970’s including Studio Museum in Harlem, El Museo Del Barrio in the Bronx, and the Bronx Museum of Art, who were focused on black and Hispanic audiences and neighborhoods. These organizations became CIG’s (Cultural Institution Groups on city owned property, in city owned buildings that receive annual line item support from the NEW YORKDepartment of Cultural Affairs) in the late 1960’s early 1970’s.

Among the important groups who played a role in shaping the discussion about ethnic representation in museums were the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition 1968 – 1969 (BECC), which was founded after the Whitney Museum’s “1930’s: Painting and Sculpture in America” in 1968 failed to include aNew YorkBlack artists. Under Henri Ghent’s guidance the group produced a counter exhibition at the Studio Museum called Invisible Artists: 1930. BECC was also involved with a critique and demonstration of Harlem on My Mind, an exhibition at the MET in 1969 curated by Allan Schoener under Thomas Hoving. Their mission statement at the time was to be “an action-oriented, watchdog organization to implement the legitimate rights and aspirations of the individual artists and the total arts community.” Later BECC was involved with an Art in Prison program and most notably worked with artists and writers in Attica before the riots in 1971.

During this time there was also a significant amount of organizing being done around gender issues in the art world. The Women Artists in Revolution (WAR), founded in 1969, an offshoot of AWC fought for women’s rights in the art world. WAR organized art actions, newsletters, posters, wrote articles, and met with museum representatives. Their mission statement and list of demands included “Museums should encourage female artists to overcome centuries of damage done to the image of the female as an artist by establishing equal representation of the sexes in shows, museum purchases, and on selection committees. As well groups like: Ad Hoc Women’s Artist’s Committee, 1970, which was formed to specifically address the low number of women artists included in the Whitney’s Annual (later Biennial) exhibition; A.I.R Gallery, 1972, the first independent woman’s gallery in the US and later the Guerrilla Girls, 1985, who combat sexism in the art world by using statically information about gender representation in museums, all added to the rise of importance of feminist issues in the art community and in major cultural institutions.

The Anti-Institutional Institutions

In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s there was a shift in the way that artists were conceiving, producing and exhibition their work. With the rise of Minimalism, Anti-Form Art, Street Works, the Fluxus Movement and Performance Art, the context for art activity moved out of the gallery and into the world. Much of the work produced during this time could not be collected in a traditional way by museums and often required specific sites, architectural settings our live audiences to be activated.

In an effort to deal with these new art forms several non-profits were founded by artists, curators and critics who wanted to provide platforms for this kind of work and also wanted to stand in opposition to the canonical and rigid collecting institutions.

Among the groups that were started during this time to address these types of issues were: 112 Workshop / 112 Greene Street, 1970 (aka White Columns), which was founded by Jeffrey Lew and Gordon Matta-Clark as a site for the production of new sculpture in unexpected materials; The Kitchen, 1971, founded by artists who were frustrated that museums and galleries were not showing video art; The Clocktower Gallery, The Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Idea Warehouse (1971) later becoming P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in 1976, founded by Alanna Heiss, whose mission was to convert abandon or under-utilized buildings into performance, exhibition or studio spaces for contemporary artists who were not shown in established museums; Artists Space/Committee for Visual Arts, 1972; started by Irving Sandler and Trudie Grace, whose mission was to provide a service organization for artists that offered exhibitions, programming by artists, a space for performance, cultural meetings, events, the Emergency Materials Fund and the Independent Exhibition Program which awarded grants to artists and groups for presenting their work in other non-profit venues and unorthodox sites; Creative Time, 1974, founded by Anita Contini, which took advantage of the economic downturn that emptied hundreds of thousands of square footage of office space in Lower Manhattan and whose original mission statement states “Public art, as presented by Creative Time, challenges both the chronic isolation of artists and the widespread notion that “Art” is an elitist pastime”; The Alternative Museum, 1974 founded with the principle that “Alternative Museums (if not all museums) should devote themselves more often to exhibitions with controversial substance, otherwise they won’t be alternatives at all”; The New Museum of Contemporary Art, aka The New Museum, 1977; founded by Marcia Tucker, a former curator at the Whitney, who had put on several controversial shows there, whose mission was to act as a “exhibition, information, and documentation center for contemporary – focusing on living artists and the work they make – work that does not yet have wide exposure or critical acceptance. The New Museums projected scope lies between the non-historically oriented alternative spaces and the major museums” and The Drawing Center, 1977, founded by former MoMA curator Martha Beck, with principle “of encouraging work on paper, and the visibility and appreciation of drawings which are often intimate, direct and experimental state of an artist’s creative process … The Gallery presents shows of promising lesser-known artists, and also historical or thematic exhibitions by established figures.”

Studio Craft Movement

The Studio Craft Movement also played a role in the development of the Alternative Arts Movement. Artists working in craft materials were interested in taking control of the means of production in craft field outside of the factory setting by setting up independent studio in urban settings. They also wanted to collaborate with visual arts and anyone else interested in working with these materials. Two organizations that were founded in New York under these auspices were: UrbanGlass, aka New York Experimental Glass Workshop, 1976 was founded in Soho in 1976 by artists who wanted to create a glass making studio in New York to make their own work and also to collaborate with visual artists, architects and industrial designers and Dieu Donné Papermill, 1976 which started in Soho as a commercial enterprise by two students who had graduated from the hand papermaking program at Madison, Wisconsin. In the early 1980’s Dieu Donne was incorporated as a non-profit and started to offer classes, residencies and exhibition opportunities and has introduced handmade paper to hundreds of artists and created an important and lasting body of work in the medium.

Are Alternative Arts Groups still viable today?

The institutions and production groups that were founded in New York during this time form the backbone of the thriving culture scene in our city. On any given night there are public programs, performances, exhibition openings, symposium, concerts etc in these spaces. There is no doubt in my mind that New York would be a much less exciting place if these spaces did not exist.

However, many of these groups are going through transitional phases of leadership, are re-evaluating their missions and must rebuild their boards and audiences as they go.

What should the values and activities of organizations of this type be in 2008?

In my opinion it is interesting to re-evaluate where these institutions stand vis a vis their relationships to the larger canonical organizations, current events and the needs of artists. In my career I have had first hand knowledge dealing with some of the transitional issues that these kinds of organizations have gone through in the 1990’s to the present as they relate to founders syndrome and coming to grips with maintaining “core values” while discarding outmoded thinking in relation to organizational culture, economic models and the new reality we live in where the cultural sector seems to privilege and absorb the contemporary in a totally overheated art market. In my mind there are new paradigms, issues and questions that need to be asked of artists, mediums and anti-institutional postures to create viable and relevant organizations for the future.

I am indebted to the exhibition at The Drawing Center called Cultural Economies: Histories from the Alternative Arts Movement curated by Julie Ault in 1996 and her follow up book Alternative Art New York, 1965 – 1985, published by The Drawing Center and the University of Minnesota Press in 2002 for much of the historical research for this talk.

Brett Littman has a unique perspective on the alternative space movement as he has worked at four non-profit organizations founded in 1976-1977 including: UrbanGlass (NY Experimental Glass Workshop), Dieu Donné Papermill, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, and The Drawing Center. Although the genesis and mission of each of these organizations are different – the aesthetic issues, politics, and economics involved, as well as the national and local arts funding situation at the time, were similar.