The Surrealists reinvented the idol of origins. They dreamed of their Primitive as someone standing apart from science and reality by curiously rediscovering the paths of history. As early as the 1920s, they were among the first to revolt against the serfage of non-Western peoples, and they did so not by calling, in the name of fine sentiments, for some moderation in the ways these peoples were being subjugated but by calling for a radical condemnation of the very conditions of colonialism.

The history of art retains especially André Breton’s passion for Eskimo, Indian, and South Sea masks and for the dolls of the Hopi Indians of Arizona, of which he kept some beautiful specimens. He did so because he admired their expressive and poetic value, the very same value he sought everywhere else as so many signs of life in a modern world whose disenchantment he tirelessly denounced.

For, the basic problem was less the other than one’s own self, caught in the nets of a Western world whose alienation and decay were being heralded by its poets. Antimodern, yet at the very heart of modernity, the Surrealists opened the way toward the kinds of reflections art history is taking note of today.

Aby Warburg, Jean Laude, and a few others have spoken of the indispensable contributions of anthropology and ethnology and of how unstable were the status of the artist and of the art work and, necessarily along with them, the criteria of uniqueness, originality, and superiority. At a time when the new Quai Branly Museum is looking like Pandora’s Box while inviting comparison with other countries and other ways of presenting collections, the remarkable studies by Nélia Dias, Sophie Leclercq, and Maureen Murphy reopen the file on a shaky identity.

More broadly speaking, we can say that it is discontent with civilization itself that was at issue here. Michel Leiris had noted the coexistence of such discontent with a culture in which everything seemed to have been said already because a certain level of technological development had been achieved but in which that development had been rendered possible only by stifling certain aspirations for the infinite.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of November 23, 2006

Sophie LeclercqThe Surrealist Appropriation of the Indigenious Arts

Especially when it came to politics, the Surrealists had a fascination with “the Other.” This they expressed through their radical anticolonialism or else via the production of poetic representations of the Negro, the Savage, the East, and so on.[ref]See Sophie Leclercq’s dissertation, Les surréalistes face aux mythes et l’Autre et au colonialisme, 1919-1962, Center for the Cultural History of Contemporary Societies, University of Versailles Saint-Quentin, 2006.[/ref] Yet the primary contact they had with distant cultures was mediated through objects. Beyond this admitted taste for “primitive” objects, it seems that the Surrealists–and, in the first place, their leader–were tempted to associate their own image with those objects in an effort at mutual identification, even appropriation, that was played out during the interwar period.

The Search for Novelty

In collecting “fetishes” very early on, the Surrealists fit into a history of collector-artists that preceded them–that is, the first generation of Primitivism. This collected exoticism little by little came to be associated with the idea of modernity. Carl Einstein had already remarked that the interest in “Negro” sculpture gave rise to an “interpretation” of these objects. Concerning this strong infatuation on the part of the Surrealists with “primitive” art, one may ask oneself whether what was expressed was a kind of anticonformism or, on the contrary, a certain sort of herd instinct, an adaptation to the trend of their milieu. Was there not already an awareness of “going modern” when cultivating this taste?

La Révolution surréaliste, n° 6, 1er mars 1926, p. 5. Fac-similé J-M. Place.

Whereas the market for “savage” art basically gathered objects from Africa and Oceania or from pre-Columbian America, the interest several Surrealists had in this area very soon bore on Amerindian art and, in particular, on the art of North America. As early as the 1920s, a number of them took an interest in Kachina dolls and Inuit masks. In 1927, Paul Éluard spoke of Pueblo dolls as “what is most beautiful in the world”[ref]Paul Éluard, Lettres à Gala (Paris: Gallimard, 1984), late May 1927 letter, p. 22.[/ref] and one of these was reproduced in La Révolution surréaliste.[ref]La Révolution surréaliste, 9-10 (October 1, 1927): 34.[/ref] The exhibition Charles Ratton organized in 1935, “Ancient Masks and Ivories of Alaska and of the Northwestern Coast of America,”[ref]Archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery, “Exposition Côte Nord-Ouest” files. Exhibition presented at the Charles Ratton Gallery from July 2 to July 27, 1935.[/ref] certainly prompted them to welcome Yup’ik masks in their own exhibition, which was held the following year in the same gallery. Yet it was presented as “the first exhibition of the kind ever organized.” While attendance at the show did not match the show’s novelty, this show did, on the other hand, arouse the enthusiasm of the Surrealists.[ref]Indeed, Man Ray purchased the least expensive of the Yup’ik masks. Elisabeth Cowling takes up the account given by Charles Ratton in her article, “The Eskimos, the American Indians, and the Surrealists,” Art History, 1:4 (1978). According to Cowling, Ratton said that he did not recall the date of this exhibition but situates it in a very uncertain way around 1931 or 1932. Our own research at the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery leads us to think that he was in reality speaking of the 1935 exhibition and that no exhibition of this kind was organized before this date.[/ref]. À cette occasion, Paul Éluard publie dans Cahiers d’Art « La Nuit est à une dimension », qu’il illustre de nombreuses reproductions de masques exposés chez Ratton[ref]Paul Éluard, “La Nuit est à une dimension,” Cahiers d’art, 10:5-6 (1935): 99-101.[/ref] On this occasion, Éluard published in the Cahiers d’art “La Nuit est à une dimension” (Night is one dimensional), which he illustrated with numerous reproductions of masks that had been exhibited at Ratton’s.[ref]Paul Éluard, “La Nuit est à une dimension,” Cahiers d’art, 10:5-6 (1935): 99-101.[/ref]

La Révolution surréaliste, n°9-10, 1er octobre 1927, p. 34.

Fac-similé J-M. Place.

While the idea of an aesthetic affinity between Surrealist art and the objects from these regions has its validity, it does not on its own explain the Surrealists’ biases. One can also see therein a search for novelty as much on the sociological level as in efforts at poetic creation. The search for the unheard of, for the completely new, played a large role in those efforts and found poetic expression in their fascination with found objects–which, as André Breton explained, incites the “precipitate of desire.”[ref]Éluard bought, for example, numerous African objects on sale from the Tual collection in 1930. Annotated Roland Tual sales catalogue, Éluard archives, Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet.[/ref], celui-ci, déjà canonisé et associé à l’idée de modernité, ne peut représenter une « trouvaille » surréaliste.

Commercial Appropriation

The Surrealists who were interested in “savage” objects were fully engaged in the activities of buying and selling. They could travel quite far within Europe for the purpose of enlarging their market. Their relations with dealers and their correspondence, just like the abundance of Hôtel Drouot auction catalogues kept by Breton and Éluard–quite a number of them, in fact, between 1926 and 1931–as well as the numerous annotations these catalogues include, reveal to what extent attendance at auctions was part of their way of life.[ref]Éluard wrote to Gala on May 25, 1927 from Paris: “I won’t be able to go to the auctions or do anything for a week” (Lettres à Gala, p. 19). For the Hôtel Druot catalogues preserved in Breton’s studio, see his archives, 42, rue Fontaine auction DVD-Rom, CalmelsCohen, 2003, lots 6067, 6071, and 6080.[/ref] The speculative aspect was never totally avoided. In 1929, Éluard wrote, for example, to Gala: “In Holland, I bought a fetish that is unique in the world, from New Guinea (2.50 meters), for 20,000 francs. It’s magnificent. One day, I will sell it for 200,000. Definitely.”[ref]Paul Éluard, Lettres à Gala, June 1929 letter, pp. 75-76.[/ref]

La Révolution surréaliste, n°9-10, 1er octobre 1927, p. 35. Fac-similé J-M. Place.

During the auction of the Éluard and Breton collections in 1931, the press did not fail to note, either, that such a sale could only be reinforced by the burning issue of the Colonial Exhibition, which was being presented at the same time.[ref]“Au hasard des ventes,” L’Ami du Peuple, July 3, 1931; archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery, Paris.[/ref] Now, Éluard and Breton were aware of “the Colonial Exhibition effect,” as the February letter to Gala testifies.[ref]“There’s a real shortage of money. I saw Ratton yesterday and he offered to sell my objects and those of Breton around the beginning of May. . . . There is at this time the colonial exhibition and he thinks that might help. What should be done?” (Paul Éluard, Lettres à Gala, February 1931 letter, pp. 133-34).[/ref] While in other respects they violently attacked the Colonial Exhibition, they were aware of the advantage they could gain from the infatuation with a certain sort of colonial faddishness.

In 1937, a notary public from Versailles put Breton in charge the gallery he named Gradiva. The gallery, of which Breton was the director, presented Surrealist works and “savage objects” side by side. This commercial venture quickly folded, but it is revealing of an at least partial acceptance of the art market that contrasts with his stark rejection of capitalism. Even though this activity of selling “primitive” objects, just like that of commerce in Surrealist paintings, was not considered to be a compromise, some Surrealists could be expelled for “journalism.” Aragon and Breton decreed that it was impossible for a Surrealist to be “at the beck and call of money.”[ref]Louis Aragon and André Breton, “Protestation,” La Révolution surréaliste, 7 (June 15, 1926): 31. Philippe Soupault detects some “contradictions” in the intransigence of his friends. Philippe Soupault, Mémoires de l’oubli 1923-1926 (Paris: Lachenal et Ritter, 1986), pp. 159 and 162.[/ref] In their minds, there were lucrative activities that harm the Surrealist spirit and other ones that are deemed acceptable, like the sale of “fetishes.”

Of course, while commerce in these objects secured some revenue for certain ones among them, the purchase thereof proceeded no less from a genuine election. Moreover, the Surrealists attached little importance to the authenticity or antiquity of such objects, and they rejected “patina” as a criterion of value.[ref]André Breton, “Océanie,” foreword to the exhibition catalogue Océanie, Olive Gallery, 1948, Oeuvres Complètes, vol. 3 (Paris: Gallimard-La Pléiade), pp. 834-39; “Phénix du Masque,” XXe siècle, new series, 15 (Christmas 1960), Perspective cavalière (Paris, Gallimard-NRF, 1970): 182.[/ref]Their passion for popular objects partook of the same logic of removing the art work from its expected settings.[ref]André Breton, preface to the Exposition surréaliste d’objets catalogue, Oeuvres Complètes, vol. 2, pp. 282-83.[/ref] Thus, their collections were made up not only of masterworks but contained also some Surrealist bric-à-brac. For this reason, the Surrealists were atypical collectors and atypical dealers, but their poetic grasp of such objects was not something that shunned a possibly opportunistic relation to them.

The Surrealist Appropriation of the “Savage Arts”

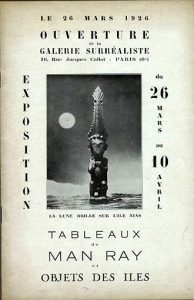

Couverture du catalogue de l’exposition Tableaux de Man Ray et objets des îles, 1926.

Archives André Breton, 42, rue Fontaine.

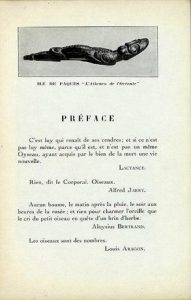

On a more basic level than commercial appropriation, the appropriation of savage art was played out symbolically through an explicit and repeated effort to make a connection [rapprochement] between these objects and the movement itself at the time of exhibitions as well as in reviews and texts. Evocatively entitled exhibitions wherein Surrealist works stood in juxtaposition to non-Western objects were organized. As early as 1926, the “Pictures of Man Ray and Island Objects” exhibition was presented for the inauguration of the Surrealist Gallery. The catalogue’s cover reproduced a sculpture from the island of Nias.[ref]Stacks of the Kandinsky Research Library, Georges Pompidou Center.[/ref] The catalogue itself was illustrated with objects from Oceania, the captions being reworked by the Surrealists–such as “Easter Island, the Athens of Oceania”–which testifies to their will to substitute these objects for the classical heritage of the West as well as to sift out new canons and new classics.

The following year, it was America’s turn to be honored. The “Yves Tanguy and Objects from America” exhibition presented, side by side, pictures by this Surrealist and objects from America, both pre-Columbian objects and more recent ones, like those of British Columbia.[ref]“Yves Tanguy and Objets from America” exhibition catalogue, May 27 to June 15, 1927, Surrealist Gallery. Stacks of the Kandinsky Research Library, Georges Pompidou Center. The objects came from, among other places, the collections of Aragon, Breton, Éluard, Tual, and Nancy Cunard.[/ref] In the text written for the catalogue, Breton established a bridge between the “ancient cities of Mexico” and the painter’s universe, which “today invites us to meet him in a place he has truly discovered.” In “D’un véritable Continent,” Éluard connected up Amerindian cultures with such Surrealist concerns as dreams and the imagination. Their comments legitimated the presentation of American objects by relating them to realms privileged by Surrealism.[ref]In 1935, this poetic connection between Amerindian cultures and the work of Yves Tanguy was to be found again in a poem by Benjamin Péret, “Je me souviens de Tanguy dormant dans les hautes branches d’un arbre,” Cahiers d’art, 10:5-6 (1935).[/ref]

This juxtaposition of non-Western objects and Surrealist products was also to be found in journals. In La Révolution surréaliste, a New Mecklenburg mask was used to illustrate “Surrealist texts,”[ref]La Révolution surréaliste, 6 (March 1, 1926): 5.[/ref] and then a set of finery and masks from New Ireland accompanied a poem by Philippe Soupault.[ref]La Révolution surréaliste, 7 (June 15, 1926): 16.[/ref]

Page intérieure du catalogue de l’exposition Tableaux de Man Ray et objets des îles, 1926.

Archives André Breton, 42, rue Fontaine.

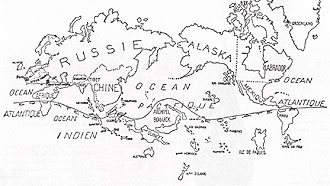

In another issue, two illustrations presented opposite each other seemed to compose a diptych, so much did the two representations formally match: on the left-hand page, a Kachina doll, on the right-hand page, a cadavre exquis.[ref]La Révolution surréaliste, 9-10 (October 1, 1927): 34-35.[/ref] The famous map, “The World at the Time of the Surrealists,” which appeared in Variétés in 1929[ref]“Le Monde au temps des surréalistes,” in “Le surréalisme en 1929,” Variétés, 1929: 26-27.[/ref] was another product of such a rapprochement. Cartography is a discipline that went along with the Age of Discovery and that partook of a logic of domestication and appropriation of the world. By engaging in a détournement of the realistic map of the world, the Surrealists reappropriated the Earth for themselves so that “the world at the time of the Surrealists” would be a world that could almost be described as Surrealist.[ref]André Thirion would later detect in this map a form of appropriation of these typically Surrealist cultures. André Thirion, Révolutionnaires sans Révolution (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1972), p. 454.[/ref] This world map echoed Paul Nougé’s “New Elementary Geography,” which appeared in the same issue. It, too, was connected with Éluard’s poem on “L’art sauvage,” which linked it explicitly to the material productions of the peoples being promoted.

Such juxtaposition, which is to be found again on numerous occasions in statements by Breton, belongs to a technique that was dear to the Surrealists: that of analogy. The purpose of presenting, side by side, an object from New Ireland and a cadavre exquis was to create ties between those two realities in order to arrive at the point where they “will cease to be perceived contradictorily,” to use the Surrealist formula. Exhibition titles, which were articulated around the conjunction and, offered confirmation through language of the principle behind the spatial design of these exhibitions. In this way, the Surrealists appropriated “savage” objects by stamping them “Surrealist.”

« Le Monde au temps des surréalistes », in : Variétés, 1929. Fac-similé.

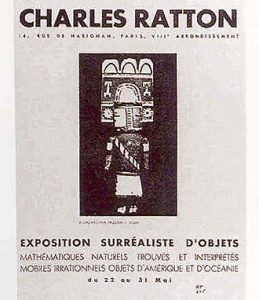

According to Krzysztof Pomian, an object that has been used in some other context and by other individuals can take on a partially transformed meaning and be laden with new signs.[ref]February 17, 2003 talk by Krzysztof Pomian in Pascal Ory’s seminar on “The Cultural Memory of the Contemporary Era,” at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.[/ref] The non-Western object presented in these exhibitions or these journals, while continuing to retain some of the signs of its “primary life” and those of its uprooting which made of it an artefact, is partially transformed once again in order to become there a sort of “Surrealist object.” This appropriation is, of course, a form of recognition. It is also a means of defining Surrealism through these objects and of forging its identity in particular upon them. Surrealism was a movement that always wanted to master its own image. The presentation of the “savage” arts partook of its intention to forge and to display a certain image of Surrealism in relation to these cultures.[ref]In this capacity, Elisabeth Cowling speaks of “surrealist propaganda for the works of art they discovered or rediscovered,” in “An Other Culture,” in Ades Dawn, Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (London: Art Council of Great Britain, 1978), p. 467.[/ref] Yet it was with the Surrealist Exhibition of Objects, which was presented from May 22 to May 29, 1936 at the Ratton Gallery[ref]See the shots of the rooms of this exhibition in the archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery.[/ref], that this effort at rapprochement really hit a snag.

The Surrealist Exhibition of Objects

Publicité pour l’exposition surréaliste d’objets (poupée kachina, Pueblos, Sud-Ouest des États-Unis), in : Cahiers d’Arts, n°1-2, 1936.

This exhibition[ref]On the attendance at and the reception of this exhibition, see the visitors’ book and the press clippings found in the archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery.[/ref] fit into one of Breton’s reflections at that time. Around then, he was also displaying, in “Crisis of the Object,” the Surrealist ambition to divert [détourner] objects from their usual purposes and to bring out “force fields” via fortuitous connections.[ref]André Breton, “Crise de l’Objet,” Cahiers d’art, (May 1936), Le Surréalisme et la peinture (Paris: Gallimard, 1965), p. 279.[/ref] His classifications into categories, like “natural objects, perturbed objects, American objects, Oceanic objects, mathematical objects,” and so on were a means of arranging the objects of the exhibition in a Surrealist way. Inuit masks, or those from New Guinea, were shown there alongside Salvador Dalí’s Aphrodisiac Jacket or Meret Oppenheim’s Breakfast in Fur.

As Maurice Henry explained in an article about this exhibition, “from an Eskimo mask in the form of a duck, a carnivorous plant, a glass deformed by lava from a volcano to a Surrealist object, there is but a step. It is quickly taken by the visitor.”[ref]Maurice Henry, “Une Exposition d’objets surréalistes. Quand la poésie devient tangible,” Le Petit journal, May 24, 1936, from the archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery.[/ref] For the journalist Guy Crouzet, all these juxtaposed objects had “a family likeness.”[ref]Guy Crouzet, “Surréalisme pas mort,” Vendredi, May 29, 1936, from the archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery.[/ref] Breton drafted the press statement that appeared under the initials “J. F.” in La Semaine de Paris[ref]The archives of the Ladrière-Ratton Gallery has a copy of this article handwritten by Breton that would leave one to assume that this text served as the press release. Published with the initials J. F. (in Breton’s handwriting) as “Exposition d’objets surréalistes,” La Semaine de Paris, May 22-28, 1936 (reproduced in his Œuvres complètes, vol. 2, p. 1199). One also finds a handwritten note by Marcel Jean who sent the article, after it had appeared, to Charles Ratton at Breton’s request.[/ref] and Éluard wrote “L’Habitude des tropiques” for Cahiers d’art. All these texts reinforce, in words, the analogy being sought after in the exhibition.

Salle de l’Exposition surréaliste d’objets, 1936.Galerie Ladrière-Ratton, Paris.

Thus, between the “Surrealist exhibition of objects” and the “exhibition of Surrealist objects,” there was but a step. Yet the first set of catalogue proofs reveals that the initially planned title was “Exhibition of Surrealist Objects.” Similarly, that title was the one for the articles by Henry and Breton.[ref]This transposition is to be found in the title of the lecture Breton gave the previous year in Prague: “Surrealist Situation of the Object. Situation of the Surrealist Object.”[/ref] The willingness to consider an Amerindian object as a Surrealist object was also expressed by the fact that the object retained in the advertising notice as emblematic of the exhibition was an Amerindian object, a Pueblo Kachina.[ref]Presentation notice for the exhibition, on the first page of Cahiers d’art, 1-2 (1936).[/ref] These “savage” objects were therefore placed center stage in the image Surrealism intended to give of itself. They were tied by analogy to Surrealist objects, combined with them for subversive ends, and ultimately appropriated so as to become “Surrealist objects.” They belong to the “Surrealist gallery” in the same capacity that Sade and Lautréamont figure within the “Surrealist pantheon.”

Bibliographie

Textes de surréalistes

Breton, André, Œuvres complètes, 3 tomes, Paris, Gallimard, La Pléiade, 1988.

Breton, André, Perspective cavalière, Paris, Gallimard, NRF, 1970.

Eluard, Paul, Lettres à Gala, Paris, Gallimard, 1984.

Eluard, Paul, « La Nuit est à une dimension », in : Cahiers d’art, 1935, n°5-6, p. 99-101.

Péret, Benjamin, « Je me souviens de Tanguy dormant dans les hautes branches d’un arbre », in : Cahiers d’Art, vol. X, n°5-6, 1935.

Thirion, André, Révolutionnaires sans Révolution, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1972.

Revues

La Révolution surréaliste, n°1-12, 1924-1929.

Variétés, « Le surréalisme en 1929 », 1929.

Analyses

Cowling, Elisabeth, « The Eskimos the American Indians and the surrealists », in : Art History, 1, n°4, 1978.

Cowling, Elisabeth, « An Other Culture », in : Dada and Surrealism reviewed, Ades Dawn, Art Council of Great Britain, 1978.

Archives

Archives de la galerie Ladrière-Ratton

Correspondances, Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet

Archives Breton, DVD-Rom, 42, rue Fontaine, Calmelscohen, 2003

Sophie Leclercq a soutenu une thèse au Centre d’histoire culturelle des sociétés contemporaines de l’Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin intitulée Les surréalistes face aux mythes de l’Autre et au colonialisme, 1919-1962. Elle travaille au département de la recherche et de l’enseignement du musée du quai Branly en tant que chargée de l’édition scientifique, où elle assure en particulier la rédaction de la revue d’anthropologie et de muséologie Gradhiva. Elle est également chargée de cours à l’Institut d’études politiques de Lille où elle anime un séminaire sur les mémoires coloniales.