The Surrealists reinvented the idol of origins. They dreamed of their Primitive as someone standing apart from science and reality by curiously rediscovering the paths of history. As early as the 1920s, they were among the first to revolt against the serfage of non-Western peoples, and they did so not by calling, in the name of fine sentiments, for some moderation in the ways these peoples were being subjugated but by calling for a radical condemnation of the very conditions of colonialism.

The history of art retains especially André Breton’s passion for Eskimo, Indian, and South Sea masks and for the dolls of the Hopi Indians of Arizona, of which he kept some beautiful specimens. He did so because he admired their expressive and poetic value, the very same value he sought everywhere else as so many signs of life in a modern world whose disenchantment he tirelessly denounced.

For, the basic problem was less the other than one’s own self, caught in the nets of a Western world whose alienation and decay were being heralded by its poets. Antimodern, yet at the very heart of modernity, the Surrealists opened the way toward the kinds of reflections art history is taking note of today.

Aby Warburg, Jean Laude, and a few others have spoken of the indispensable contributions of anthropology and ethnology and of how unstable were the status of the artist and of the art work and, necessarily along with them, the criteria of uniqueness, originality, and superiority. At a time when the new Quai Branly Museum is looking like Pandora’s Box while inviting comparison with other countries and other ways of presenting collections, the remarkable studies by Nélia Dias, Sophie Leclercq, and Maureen Murphy reopen the file on a shaky identity.

More broadly speaking, we can say that it is discontent with civilization itself that was at issue here. Michel Leiris had noted the coexistence of such discontent with a culture in which everything seemed to have been said already because a certain level of technological development had been achieved but in which that development had been rendered possible only by stifling certain aspirations for the infinite.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of November 23, 2006

Maureen MurphyBetween Arts Works and Documents:

The Arts of Africa in Paris and New York in the 1930s

Considered a passing fad in the 1910s, avant-garde artists’ persistent interest in African, American, and Oceanic (A-O) arts[ref] We shall use the abbreviation A-O in order to designate the arts of Africa, Asia, America, and Oceania and so as to avoid such adjectives as primitive, first, initial, or tribal. This abbreviation is but an expedient while we wait for the artistic productions of these regions of the world to be grasped separately and for the sake of their own specific characteristics.[/ref] began to annoy more and more people by the end of the 1920s. For Waldemar Georges, “this worship of barbarism, this return to an initial state of civilization, has become a form of academicism,”[ref]Waldemar Georges, “Le crépuscule des idoles,” in Les Arts à Paris, 17 (May 1930): 7.[/ref] while others declared that it was time to “return to our clear traditions, those of a race that has already proved itself.”[ref]Fernand Hure, “Procès d’une farce dramatique,” in Le Publicitaire (undated, but probably published around 1930). Review of the Percier Gallery, 1930-1931, archives of the Percier Gallery, Kandinsky Library, French National Museum of Modern Art/Center for Industrial Creation, Paris.[/ref] The Musée de l’Homme (French Museum of Man), whose staff was built up around Paul Rivet in the late 1920s, was born in this context of growing tension and increasing xenophobia. Anxious to make objects brought back from the colonies better known and to cultivate an appreciation of the values of otherness, this new institution upheld the documentary value of these objects as well as a contextualized approach. Despite displays of reaction against a “wholly aesthetic” view, A-O objects were still far from being accepted as works of art–as the reception of an exhibition such as the one organized by Tristan Tzara, Charles Ratton, and Pierre Loeb at the Pigalle Theater Gallery in 1930 testifies. Similarly, in modern art, the new representational norms introduced by the A-O arts gave rise to disbelief and violent reaction. In order to underscore better the pendulum-like process the status of these objects experienced, shifting as it did between works of art and documents in the 1930s, we shall endeavor to retranscribe here the entire complexity of this moment by addressing the creation of the Musée de l’Homme, the “Exhibition of African Art and Oceanic Art” at the Pigalle Theater Gallery in 1930, and the photographs of African objects taken by Man Ray and by Walker Evans around 1935.

The Creation of the Musée de l’Homme or the Documentary Bias

“Ever since certain classes of ethnographic objects–in particular African and then Oceanic sculpture–have been annexed to the domain of artistic curiosity at the instigation, a few years before the war, of artists from the Paris School, a rift has grown between the public, which has acquired this taste, and the curators of ethnographic museums.”[ref]Georges Henri Rivière, “De l’objet d’un musée d’ethnographie comparé à celui d’un musée de Beaux-arts,” Cahiers de Belgique, 9 (November 1930): 310.[/ref] Georges Henri Rivière, who was named Rivet’s assistant director at the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography in 1928, offered this assessment in 1930. For him, there was nothing surprising about the fact “that such a false conception of ethnography would have developed in our artistic avant-garde.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref] The dilapidated state in which these artists had found the Museum of Ethnography[ref]A propos of the history of the Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography, see Nélia Dias, Le Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro 1878-1908. Anthropologie et muséologie en France (Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1991).[/ref] could, according to him, justify the deplorable image they would have had of the discipline as well as their desire to “build up very quickly a ‘Louvre’ to bring together in it all the beautiful pieces of primitive art.”[ref]Ibid., p. 310.[/ref] Rivière, however, deplored such an approach: transformed, adapted to the taste of the moment, A-O works would then be presented in a way that would fail to do justice both to their proper functions and to their original values. The whole difficulty with the Musée de l’Homme project resided in this tension between the need to respond to those who would have liked to see the objects of Africa and Oceania exhibited in a Fine Arts museum and the desire of ethnographers to revitalize their discipline by designing a kind of museography that could highlight the original and supposed meaning of such objects as well as their artistic qualities. The aesthetic approach, however, did not enjoy unanimous backing–far from it–within French society, as the debate triggered by the “Exhibition of African Art and Oceanic Art” at the Pigalle Theater Gallery in 1930 itself testifies.

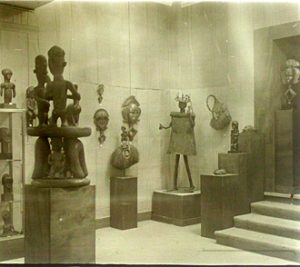

View of the “Exhibition of African Art and Oceanic Art” at the Pigalle Theater Gallery in 1930. Set of uninventoried and unpublished glass plates, French Society of Photography, Paris.

The Exhibition of African Art and Oceanic Art at the Pigalle Theater Gallery in 1930

“The exhibition of Negro and Oceanic art at the Pigalle Theater . . . upset the sensibilities of all the guardians of morality,”[ref]“Art et pudeur” in Cahiers d’art, 1930.[/ref] one could read in the review Cahiers d’art in 1930. “To calm a few countries worried about the virtue of their young ladies,” one could also read, “the gallery owner, Baron Henri de Rothschild, has expelled from the room a few statues that did not seem to him to have been clothed in exemplary fashion.”[ref]Ibid.[/ref].Reacting against this form of censorship, the organizers of the exhibition (Tristan Tzara, Charles Ratton, and Pierre Loeb) demanded that “the chief judge of the Seine court appoint an expert to give his opinion on‘the purely artistic character of the exhibited works.’” The argument for art won out over the reservations of Baron Rothschild and the pieces were reintegrated before the courts had to intervene.[ref]This anecdote, which is emblematic of the changes and tensions at work in society during that era, is reminiscent of another one–that of the lawsuit filed, three years earlier, by Constantin Brancusi against the United States Customs Service, which had seized his sculptures on the grounds that they were industrial products. See Brancusi contre États-Unis: un procès historique, prefaced by Margit Rowell (Paris: Adam Biro, 1995).[/ref] Whether it was a matter of the African art exhibited at the Pigalle Gallery or the modern art inspired by it, it was the very status of the object that was at stake during this era. The idea of otherness and of contrast, the almost dichotomous opposition between the Beautiful or the granted and the foreign and strange or the degraded was at the heart of the approach taken by an artist like Man Ray.

Man Ray, alternate version of Black and White; glass plate, ca. 1921. Man Ray photographic collection, Georges Pompidou Center, Paris. High-resolution scanned version available.

Man Ray: Between Black and White

In a preliminary, unpublished version of the photograph Black and White that appeared on the cover of the Dadaist review 391 in 1924, two sculptures were set facing each other: a Baoulé sculpture from the Ivory Coast and an Art Nouveau figure representing a European woman. Symbol of a Western “classic,” the latter was opposed on a symbolic level to the Baoulé sculpture but seemed to be establishing a dialogue with her by offering her a flower. In response to the Baoulé sculpture’s hieraticism and its marked forms, we have the curves of the European woman, set on one hip, with one arm over her bust and the other outstretched toward her “companion” as if to ask her to dance. The two sculptures are set on a garden chair that is covered with a musical score. This detail might offer several interpretive leads from the context in which the artist executed this composition: close to nature, the white woman (symbolizing the West) and the Baoulé sculpture (symbol of Africa) face each other in a dialogue of bodies accompanied by musical notes arranged under their feet in the form of an invitation to dance. Here, however, nature is neither “savage” nor tropical. They are in a garden, which might be suggesting that, both of them cultivated (in the sense of esteemed, pampered), the woman, like African art, could give birth to “another” culture –a culture no doubt happier and richer than the current one. As for the musical score, it might be understood as an allusion to jazz. Considered as being, in music, as subversive as African art was in the plastic arts, jazz constitutes, in some sort of way, the counterpart to “art nègre” as well as its substrate; it is the backdrop on which the objects are to be apprehended.[ref]A propos of this, see Jody Blake, Le tumulte noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1930 (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, 1999).[/ref] Would Georges Henri Rivière, himself a musician and a great jazz enthusiast, have deplored such a staging for the Baoulé object ?[ref]A propos of Georges Henri Rivière, see Nina Gorgus, Le magicien des vitrines, le muséologue Georges Henri Rivière (Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2003).[/ref] Or would he have appreciated the egalitarian and dialogic values brought out by this photograph? Between the artistic approach and the documentary approach, compromise seems impossible. In photography, however, a new trend was in the process of developing, one that associated “two poles that until then were considered irreconcilable.”[ref]Olivier Lugon thus wrote: “Before the 1920s, not only did the documentary not constitute a aesthetic genre but was the negation thereof. Yet suddenly, around 1930, these two hitherto irreconcilable poles found themselves deliberately brought together in numerous photographic projects” (Le style documentaire. D’August Sander à Walker Evans, 1920-1945 [Paris: Macula, 2001], p. 15).[/ref] “If one can legitimately speak of a wave of the ‘documentary style’ during the interwar period,” writes Olivier Lugon, “it was not only that these types of images were then appearing–they had existed for a long time–but especially that they had suddenly found a name, a theoretical framework, and that they were emerging as an aesthetic category.” Present in Europe since the Renaissance, the A-O arts, for their part, had become the object of the same phenomenon of theoretical and aesthetic emergence in the 1930s. A new sensibility was leading some artists to look into what had, until then, been thought to pertain exclusively to the domain of the documentary and of ethnography and were considered to have some value in relation to the object or to the culture being represented but not to have any genuine value in itself. At the juncture between these two movements of convergence toward objects hitherto situated outside the field of art, the series of photographs of African works taken by Walker Evans for New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) on the occasion of the 1935 African Negro Art exhibition made their mark.

Walker Evans and the Arts of Africa

While Paris was considered, until the 1930s, the capital of “Negro” art, New York organized a major exhibition of African art in 1935 that rivaled all those organized until that date. For this young institution, it was a matter of affirming its place on the modern-art scene and of rivaling Paris by organizing a prestigious exhibition in homage to one of the main sources of inspiration for the European avant-garde. Of the six-hundred pieces exhibited, nearly four-hundred-and-sixty were photographed by Walker Evans, from whom the Museum had commissioned a series of portfolios to be distributed among various American universities with the aim of making African art better known in the United States.[ref]A propos of this, see Virginia-Lee Webb, Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art, 1935 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum, 2000).[/ref] While the photographs were supposed to be purely documentary in character, they nonetheless also brought out an aesthetic inherent to photography and dear to the institution in question. Indeed, Evans made no basic changes in his technique when photographing these sculptures. As with his views of buildings or streets, he took a head-on approach, framing tightly around the object,[ref]Evans trimmed his negatives so that the edges of the photograph would be as close as possible to the object. On this point, see Virginia Lee-Webb, p. 35.[/ref] which was itself placed at the center of the composition; no low-angle shots or plays of light and shadows that might express the photographer’s subjectivity opposite the object were used. Evans rejected pictorialism (moreover, he positioned himself firmly against the approach of Alfred Stieglitz), championing realism, absolute neutrality, and the elimination of all subjectivity from the work. The gap between the object and its reproduction disappeared and the photographed subject became the photographed object. These photographs almost came to substitute themselves for the sculptures. In sum, this approach concurred with that of the exhibition’s curators: in the MoMA rooms, the works were to be grasped outside their original context, and disconnected from other possible works belonging to the same geographical area or the same period of creation, as pure plastic creations echoing the modernist aesthetic. If Evans’ photographs came to substitute themselves, qua subject, for the sculptures photographed, one might say, similarly, that in African Negro Art, A-O objects lost their status as subjects so as to becomes objects of modern art. It was therefore less a matter here of disseminating “another” culture or “other” values[ref]In the catalogue, the only information concerning the objects was written in the form of captions. It does not seem that the portfolio was accompanied by any texts of an in-depth nature. On the other hand, Professor Franz Boas, who at the time headed Columbia University’s Anthropology Department, was invited to give a lecture on the arts of Africa on April 17, 1935. See Virginia Lee-Webb, p. 23.[/ref] than of consolidating an aesthetic canon that was in the processing of being built up, via the arts of Africa.

Conclusion

After World War II, the arts of Africa continued their institutional displacement from the sphere of anthropology toward that of the Fine Arts. Bled dry by the war, France could no longer maintain the role of capital of the arts.[ref]Apropos of this, see Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).[/ref] New York took over that role with the inauguration of the Museum of Primitive Art, founded by Nelson A. Rockefeller in 1957, just a few steps away from MoMA. Intimately linked together as much on the administrative level as on the level of the aesthetic being promoted, these two institutions endeavored to promote modern art and A-O art. In 1967, Rockefeller donated his collection to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, which in 1982 inaugurated a Michael C. Rockefeller wing devoted to these objects. In France, an event of such symbolic importance would not occur until twenty years later with the inauguration of the Louvre’s Pavillon des Sessions. The Quai Branly Museum, which is devoted to the arts of Africa, America, Asia, and Oceania, opened its doors to the public in 2005. In both cases, the bias in favor of the aesthetic won out over the one favoring the document. In light of the reflections, research efforts, and debates that are today emerging in the history of art as well as in anthropology,[ref]See, for example, Les cultures à l’oeuvre. Rencontres en art, ed. Michèle Coquet, Brigitte Derlon, and Monique Jeudy-Ballini (Paris: Adam Biro, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’Homme, 2005).[/ref] a third way should be able to take shape, one that would reconcile art and the document, as well as the history of art and anthropology, for the sake of an approach to A-O arts that would take into account the history and reception of these objects in the West and would do so within a broader multidisciplinary perspective.

Bibliography

Brancusi contre États-Unis: un procès historique. Prefaced by Margit Rowell. Paris: Adam Biro, 1995.

Blake, Jody. Le tumulte noir, Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz Age Paris, 1900-1930. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University, 1999.

Dias, Nélia. Le Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro 1878-1908. Anthropologie et muséologie en France. Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1991.

Gorgus, Nina. Le magicien des vitrines, le muséologue Georges Henri Rivière. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2003.

Guilbaut, Serge. How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Lugon, Olivier. Le style documentaire. D’August Sander à Walker Evans, 1920-1945. Paris: Macula, 2001.

Rivière, Georges Henri. “De l’objet d’un musée d’ethnographie comparé à celui d’un musée de Beaux-arts.” Cahiers de Belgique, 9 (November 1930).

Webb, Virginia-Lee. Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art, 1935. New York: The Metropolitan Museum, 2000.

Maureen Murphy defended a thesis in art history at the University of Paris-I (Sorbonne) entitled Stratification et déplacements d’un imaginaire: les arts d’Afrique dans les musées et les expositions, à Paris et à New York, des années 1930 à nos jours (Stratification and displacements of an imaginary: the arts of Africa in Paris and New York museums and exhibitions from the 1930s until today). After having worked for three years at the Quai Branly Museum on the D’un regard l’Autre (“Regarding the Other”) exhibition, she is now project leader for the Cité nationale de l’immigration’s inaugural exhibition, provisionally entitled 1931, which will broach the questions of colonization and immigration in France in 1931.