We already knew the role the Armory Show of 1913 had played in the transatlantic exportation of European modernity. At the initiative of artists themselves, a number of foreign painters were able to achieve recognition in America as precursors of modernism. Cézanne in particular benefitted from the wave of exportation of French Impressionism before coming to embody a model of the autonomous artist who is not subject to any movement.

Before that time, and as early as 1870, the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel had presented works by Monet and Pissarro for the first time in his gallery on New Bond Street in London, where the only kind of foreign art then admired belonged to the Barbizon School. In fact, the Impressionists had as much trouble gaining acceptance in England as they did in France. Pissarro, for example, complained in 1871 of the inhospitableness of the English as well as of his colleagues’ rudeness, indifference, and selfish jealousy. And yet, for modern painters to become established in England, all that was needed was a few decades, during which time a high-quality speciality press developed and some inspired critics emerged. In the meantime, the case of England–though the phenomenon was still more pronounced in Germany–shows to what extent the history of art intersects with questions of identity. The issue of nationality had quite an influence, especially for opponents of modernity who saw modernism as part of a betrayal of the national consensus. In her thesis on Cézanne’s reception abroad, Laure-Caroline Semmer has reconstructed these stakes, showing to what extent the painter was instrumentalized by all sides in support of the most contradictory causes.

While Cézanne himself was hardly a strategist, except in the area of his passion, other artists were more aware of the stakes involved in their careers. This is one of the favorite topics explored by Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, who studies the ways in which the various forms of Paris avant-garde painting between 1855 and 1914 became internationalized. Her sociological approach leads one to open one’s eyes about how a detour abroad helped artists who did not always enjoy full legitimacy at home. This is bound to remind one of Daniel Buren’s own long listing, in his Écrits, of the voyages he undertook between September 1978 and July 1979. The following entries are just the start:

Paris–New York: September 14, 1978

New York–Halifax (Canada): September 25, 1978

Halifax–Montreal: October 2, 1978

Montreal–New York: October 5, 1978

New York–Philadelphia: October 18, 1978

Philadelphia–New York: October 19, 1978

New York–Paris: October 20, 1978

Paris–Cologne: October 23, 1978

Cologne–Paris: October 25, 1978

Paris–Liège: October 26, 1978

Liège–Paris: October 26, 1978

Paris–Zurich: November 1, 1978

Zurich–Milan: November 2, 1978

. . . Etc.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Seminar of June 22nd, 2006

Béatrice Joyeux-PrunelThe Paris Avant-Gardes. 'A prophet is not without honor save in his own country :

A Cultural Transfert and Its Cases of Mistaken Identity

It is often asked how the various historical avant-gardes were able to persist in their avant-gardism when support from the art market was denied them out of hand. By avant-garde, we mean a position of rupture within the artistic field. How did they, even more astonishingly, succeed in gaining recognition? A comparative study of the confrontation between these avant-gardes and their publics on the international level offers, after many other studies, some answers to these questions.

From the Realism of the 1850s to the virulent varieties of futurism [avenirisme] in the 1910s, artistic innovation was made possible by avant-garde painting’s physical as well as symbolic detour abroad. This detour allowed artists to remain avant-garde within the Parisian field while at the same time exporting a more saleable kind of painting. On the symbolic level, especially, the proverb that “A prophet is not without honor save in his own country” was able to provide a basis for the legitimacy of avant-garde claims about the internationalization of their careers, stirring European elites’ national guilty consciences.[ref]Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, “Nul n’est prophète en son pays” ou la logique avant-gardiste: l’internationalisation de la peinture des avant-gardes parisiennes, 1855-1914 (History thesis supervised by Christophe Charle), University of Paris-I (Sorbonne), 2005.[/ref]

This internationalization was rendered possible by the large range of cultural divisions among various countries: not only did one not know in one country what was being exhibited in another one, but also art was not looked upon in the same way from country to country, public expectations as well as the roles assigned to art not being the same. One could therefore work to adapt avant-garde exhibitions abroad. From the Realist period onward, the artists themselves, then increasingly their dealer friends, critics, and collectors, took charge of this vast movement of cultural transfer, but at the risk of making many compromises.

The Realistic Realist Heritage: Differentiating One’s Production

Gustave Courbet, Stag Taking to the Water, 1861, Marseilles, Museum of Fine Arts.

From Realism to Impressionism, the various avant-gardes did not hesitate to alter their production according to their different markets: avant-gardist for France, more commonplace abroad. As early as the 1850s, Courbet wished to sell his huge paintings of stags in England and Germany, explaining to Champfleury in 1860, “This is a place for big hunts, Germany; it is a place of great nobles or little ones, who are there to spend money.”[ref]Letter to Champfleury, Ornans, October 1860, in Correspondance de Courbet (Paris: Flammarion, 1996), p. 163. [/ref] Where had Realism’s social and political advocacy gone?This strategy was implemented in a systematic way within the network of the Naturalists. Determined since 1858 to find some outlets in England while remaining avant-garde within the Parisian field, Whistler, Fantin-Latour, and Alphonse Legros based their strategy on a specific type of production for London collectors. Fantin-Latour began by making copies of canvases of the old masters for these collectors and then launched into the production of still lifes and portraits whose existence he did not wish to make known in Paris. These three undervalued kinds of artistic activity made him feel ashamed, as his letters reveal. Nevertheless, they enabled the artist to earn a living. As if to exorcize this compromise, Fantin-Latour attacked academicism all the more in painting-manifestos he sent to the Paris Salon, such as L’Hommage à Delacroix (Homage to Delacroix) in 1864.

Fantin-Latour, Still Life with Flowers and Fruit, 1862, Paris, Orsay Museum.

Such practices presupposed a national conception of tastes and styles that in fact permeated the minds of avant-garde artists as much as those of their contemporaries. Well established in the Realist tradition and a member of the Impressionist group, Camille Pissarro had always hoped to sell abroad. Around 1883, he decided to create, for the English market, some etchings whose picturesque quality might make one forget his “coarseness,” and therefore might interest an English public that was “sophisticated” and yet in search of some of the sensations of rural life.

Fortified by these reflections on national tastes, some modern-art dealers themselves changed what their artists’ production for foreign markets–be it only by exhibiting them alongside well-recognized canvases. Durand-Ruel did this systematically in his London exhibitions after 1870, then in New York after 1886. Relying on artists, collectors, and brokers who were willing to help him with his export business, he followed a strategy that mixed Impressionist canvases with other, well-recognized ones, especially those of the School of 1830, thereby offering a calmed-down interpretation of Impressionism’s innovations.

Post-Impressionism Translated for Foreign Countries, To the Point of Mistranslation

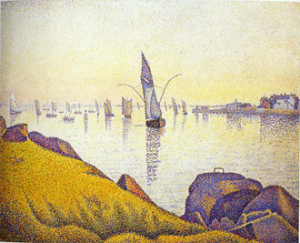

A kind of modern painting that had inherited a great deal from Impressionism began to gain recognition in Paris and then internationally after 1889-1890. Starting at that time, networks of European critics, dealers, and collectors interested in modern art were established. Leaning on this structure, the Post-Impressionists (Neo-Impressionists, Symbolists, and Nabis) were able to forge alliances with various avant-gardes abroad. To this end, they had to modify appreciably their aesthetic messages. Between Paris and Brussels, Signac changed the titles of his paintings: the musical names for the titles he chose for the Salon of the XX in Brussels in 1892 adapted his painting to the expectations of Belgian modernists keen on new music, whereas two months later, for Paris’s Salon of Independents, Signac renamed his canvases, setting them within the French landscape tradition.[ref]See Françoise Cachin, “Le paysage du peintre,” in Pierre Nora, ed., Les Lieux de Mémoire, tome 2, La Nation (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), vol. 1, “L’Immatériel–Paysages,” pp. 957-96.[/ref]

Paul Signac, Concarneau, 1891, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The cultural transfer of Post-Impressionism took place on a large scale when, about 1900, some middlemen came forth with the intention of introducing it abroad. In Germany, under the leadership of Count Kessler and of the critic and art dealer Julius Meier-Graefe, the Pointillists and the Nabis, who did not like each other, were presented as the united brothers of Impressionism, which they in fact fiercely rejected. The interpretation of this catchall “Neo-Impressionism” as the culmination of the evolution of painting toward material reality wiped away the scientific and political import of Pointillism as well as the religious orientation of Nabism. At the risk of mistranslation, the canvases of Maurice Denis enjoyed success in Germany within atheistic and Nietzschean circles for whom art was a new religion, whereas for Denis, art was to be put in the service of Christ. The disparity was just as striking between the “revolutionaries in pumps”[ref]“Diese Kunst träumt von Revolution und Umwertung aller Werte und geht en escarpins einher” (Karl Scheffler, Henry van de Velde [Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, 1913], pp. 45-46). [/ref] who welcomed Pointillist paintings of Signac in Germany at the turn of the century and the latter’s social-anarchist choices.

The New Strategies of the Avant-Garde in the Face of the Internationalization of Art

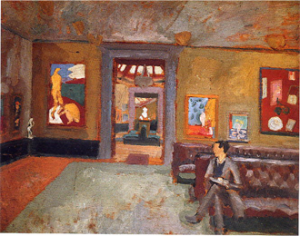

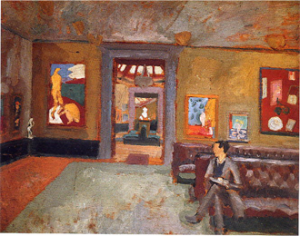

The Matisse room at the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, at the Grafton Galleries, attributed to Roger Fry (1866-1934), sometimes to Vanessa Bell (1879-1961), Paris, Orsay Museum.

After 1905, the internationalization of the modern-art market and the increasing intervention of the press in artistic debates made it trickier to differentiate artistic discourses from one nation to another. Exportation of Parisian avant-garde art was taken over by art professionals who took care to preserve the indispensable information gap between countries, conscious as they were of its importance in building up artists’ reputations. In particular, the dealer Ambroise Vollard gambled on his artists’ presence in foreign markets in order to raise their real as well as symbolic value.

It thus became indispensable to win acceptance for the avant-garde abroad, and various strategies were adopted toward this end, toning down being the most widespread tactic. The works of Matisse exhibited abroad after 1905 are, for example, tamer in style than that found in his Parisian exhibitions, which witnessed the triumph of Fauvism. Toward Belgium and Germany, the Fauve, who soon gained support from Félix Fénéon and the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery, exported softly-colored still lives, not his green-nosed portraits. In America, it was not the painter of color who was exported but, rather, the excellent artist of black-and-white drawings. After 1910, more Fauve-like canvases were exported, but they were now being interpreted in a decorative and soothing vein–as at the Grafton Galleries in 1912, under the leadership of Roger Fry.

After 1910, the development of international artistic polemics, the internationalization of the avant-gardes and of their reviews, and the appearance of major international arts fairs prompted the use of some more subtle strategies. Some, like Robert Delaunay or Marc Chagall, again chose to exhibit works whose orientations varied from country to country, sometimes touching up their canvases, changing titles, and even, as Delaunay did with the help of Apollinaire, commenting on their works in different ways for Berlin, Moscow, and New York. In 1913-1914, Delaunay exhibited in France some of his still representational works, which celebrated the influence of Paris as world capital of modern art, whereas he sent along abstract works and cosmopolitan messages to Der Sturm Gallery in Berlin.

The Parisian dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, who was less beholden to the prevailing nationalism, implemented a radically new strategy: that of absence from Paris, complemented by retrospectives abroad. Picasso’s paintings, for example, could be seen only at his dealer’s gallery, among a few collectors, or abroad. Not only did the painter gain a reputation for having an international career, and therefore a legitimacy abroad, but his absence from the Parisian field once again created the ideal dearth of information to support the idea that his works were in short supply and to maintain the myth of an artist rejected in Paris but prized elsewhere. Abroad, Picasso’s painting was presented in a retrospective way: always exhibiting pre-Cubist works among those shown, the point was to prove in visual terms that the artist was a good illustrator and that he had come to Cubism through a gradual intellectual evolution. Cubism became the culmination of a basic philosophical reflection on pictorial creation itself. This extremely convincing demonstration made through the use of images still permeates our history of modern art.

Thus, the various avant-gardes did not achieve their dominance on account of their genius alone. Rather, they knew how to invent their place within society and in the art of their time, through strategies involving creation of works, exhibition of them, and discourses thereupon. This conclusion prompts one not to grant too quickly, to the aesthetic theories of artists and to their works, a homogeneity that they did not have either in time or in space. It also suggests that one should see, at the sources of modern art’s development, a constant manipulation on the national and international levels that undermines any approach to the history of art in terms of national as well as international art. Does this conclusion endanger the aura of the various avant-gardes? Yes, if their originality is limited to that of an authenticity they did not always possess. But no, if it prompts one to inquire in a new way about the originality and intelligence of the actors who knew how to gamble on their publics and to undo their era’s cultural, artistic, and political rules of the game.

Bibliographie

Assouline, Pierre. L’homme de l’art. D. H. Kahnweiler 1884-1979. Paris: Balland, 1988. Reprint. Paris: Folio 1999. 732 pp.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Les Règles de l’art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire. Paris: Seuil, 1992. 2nd ed., revised and corrected, 1998. 567 pp.

Charle, Christophe. Paris fin de siècle. Paris: Seuil, 1998. 320 pp.

Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler–marchand, écrivain, éditeur. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, 1984. 197 pp.

Espagne, Michel. Les Transferts culturels franco-allemands. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1999. 286 pp.

Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice.“Nul n’est prophète en son pays” ou la logique avant-gardiste: L’internationalisation de la peinture des avant-gardes parisiennes 1855-1914. Doctoral Thesis supervised by Christophe Charle. Paris: University of Paris-I (Sorbonne), 2005. 950 pp.

Huth, Hans. “Impressionism comes to America.” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 6:29 (April 1946): 225-254 pp.

Jensen, Robert. Marketing Modernism in Fin-de-siècle Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996 (1994). 367 pp.

Kostka, Alexandre. “Der Dilettant und sein Künstler: die Beziehungen Harry Graf Kessler-Henry van de Velde.” In Klaus-Jürgen Sambach and Birgit Schutte, ed. Henry van de Velde. Ein Europäischer Künstler in seiner Zeit. Cologne: Wienand Verlag, 1992, pp. 253-273.

White, Harrison C. and Cynthia White. La Carrière des peintres au XIXe siècle: du système académique au marché des impressionnistes. Paris: Flammarion, 1991 (Canvases and Careers, 1965). 167 pp.

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel a former École Normale Supérieure (Rue d’Ulm) student with a teaching certificate in History, defended her history thesis at the University of Paris-I on “‘A prophet is not without honor save in his own country’ or the Avant-Gardist Logic: The Internationalization of Parisian Avant-Garde Painting, 1855-1914.” Using the methods of the sociology of art, that of cultural transfers, and the results of analysis of a data base derived from exhibition catalogues, she has retraced the international strategies Parisian avant-gardes employed to gain recognition. She has taught at the University of Reims and the Louvre School and has just been selected to teach contemporary art history at the École Normale Supérieure (Rue d’Ulm). Joyeux-Prunel participates in the “Cultural Capitals” group of the Institute of Modern and Contemporary History at the French National Center for Scientific Research and is a contributor to the joint project, coordinated by the Orsay Museum, to create an online data base of exhibition catalogues. She is currently writing a cultural history of avant-gardes (1848-1968) for Gallimard Press’s “Folio Histoire” imprint.