Charlotte Foucher Zarmanian is known for having extended the perimeter of research devoted to women. Here, she studies the issue of the conservation of things in the National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions (Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires, MNATP), which was created in 1937. In taking a close look at the work of Agnès Humbert and Suzanne Tardieu at the MNATP, she sheds light on their singular relationship to minor objects, which are the fruits of forms of know-how that ensure a connection between art and forms as well as between art and life. She leads us to discover their singular points of view on the museography and scenography of museum collections: beyond the aesthetic principle, what was at issue was to make the MNATP a scientific laboratory for research while interesting the public in the “social” portion of art.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Hartung-Bergman Foundation Seminar

Agnès Humbert, Suzanne Tardieu, and Ethnographic Things at the French National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions

Charlotte Foucher Zarmanian

Fig.1. Agnès Humbert in front of her bookshelves, ca. 1935, Paris, private collection © all rights reserved.

The perimeter of research on the production, consumption, and collection of things has already been well broached as concerns the feminine side of such histories. A blind spot nevertheless remains, which is that of the conservation of things. Were women absent therefrom? Or, more plausibly, did they play a role in some specific, though less visible enclaves? Some reflection on ethnographic things within the particular framework of the French National Museum of Popular Arts and Traditions (Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires, MNATP) would allow us to offer a few answers. Created in 1937, this museum was devoted to enhancing the value of the French side of its ethnographic collections “in its least official, most popular, and most everyday aspects” (Weber, 2003). Alongside Georges Henri Rivière, André Varagnac, and Louis Dumont, two female art historians notably participated in its establishment. They were Agnès Humbert, who defended the idea of making working-class culture a part of the French national heritage (Foucher Zarmanian, 2017), and Suzanne Tardieu, who turned the domestic arts into a genuine field of study. A brief look back on their careers allows us to examine their relation to things while investigating whether those things can also be considered women’s things.

The Dignity of Things

Fig.2. Agnès Humbert, “L’art dans la vie. Folklore et musée,” Clarté, 8 (March 1937) © all rights reserved.

Taking an interest in ethnographic things leads one to redefine how we perceive what we understand by the term art. Does art have to be solely great, precious, and unique? Or can it be something else: everyday, familiar, useful, vernacular, and vulnerable? For Humbert and Tardieu, art’s connection with life is of central importance. The “Art in Life” column Humbert ran for the antifascist review Clarté produced a series of politically engaged articles, like the one that redefined folklore as something no longer to be confined to a fusty old culture, a culture allotted to the female world in the sense of being modest and devalued, but meant to become a field of studies, that of “ethnography” (Humbert 1937). Humbert pleaded not only for the preservation of popular art but also for the less obvious preservation of various forms of know-how. In her work, she took an interest as much in popular pottery and in an exhibition set up by workers as in the history of revolutionary celebrations.

For Tardieu, who joined the MNATP in 1940 and then was named head of the department of collections in 1943, the issue at hand was to legitimate the domestic arts. It was a matter of conferring upon them a national-heritage status that was less forcefully stated in political terms, as Humbert had done, but whose objective—offering a reappraisal—was no less ambitious. For, the domestic arts are quite heterogeneous in character; they not only fulfill practical functions, as relates to the manner in which one heats, lights, cooks, eats, and washes, but attest, too, to rituals and ways of living (a girl’s communion certificate, family archives).

From Inventory to Museum

From 1937 to 1940, Humbert drew up, alongside Dumont, an inventory of objects belonging to the old Trocadéro ethnographic museum that were meant to constitute the initial holdings of the MNATP. This task of filing and classification (4,000 objects in 1939) grew considerably between 1941 and 1946, thanks in particular to Tardieu, who drew up of a list of more than 35,000 index cards concerning domestic amenities.

Fig.3. Mademoiselle Girbal answering questions from Suzanne Tardieu, cooperative research for the Aubrac program (1964-1966), Marseille, Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilizations (MUCEM) photo library © all rights reserved.

In order to expand these collections as well as documentation about them, Tardieu and Humbert also had recourse to participant observation. Humbert collaborated in 1938 in the Sologne project, the first large-scale collective investigation intended to document one of the open-air regional museums that was to complement the Parisian museum. And Tardieu went on assignment after assignment to build up a collection of domestic arts and objects. Without neglecting to examine notarial archives, direct observation among villagers and, in particular, “a visit to outbuildings . . . can prove fruitful,” she said. “There, one can find pieces of furniture that have had their hours of glory, but have been abandoned, and whose function has been completely transformed” (Tardieu, 1976). From a microscopic approach to objects to more macroscopic conclusions, what was now going to have to be shown is how such pieces, taken as a whole, can contribute to one’s analysis of changes in domestic amenities over the course of a human life, and more broadly within a local society.

Fig.4. Poster: “Objets domestiques des provinces de France dans la vie familiale et les arts ménagers” (Domestic objects from the French provinces in family life and the domestic arts), MNATP exhibition, 1953 © all rights reserved.

Humbert participated in the design of the MNATP’s first exhibition gallery about “The People of France, its Crafts and its Leisure Time.” As a layout dating from 1936 shows, living environments and cultural practices as well as folk traditions and folk objects were to be placed side by side within the same space. Nonetheless, this first layout was altered by Rivière: the retrospective look at changes in workers’ lives proposed by Humbert had disappeared from the room dealing with towns, as did the section on mines, in favor of a more expansive presentation of working-class neighborhoods and their popular festivals, along with craft workers and their instruments of labor.

Tardieu’s thesis about domestic objects around “home and hearth” also provided her with the opportunity to submit a critical study about the museum itself, which “is not to be solely . . . a museum containing beautiful objects [but] has to aim to become more and more a laboratory for scientific research” (Tardieu, 1945). Her important work of inventorying was leading in this direction and allowed her to draw up a positive report on what the MNATP then possessed and a negative one indicating the gaps still to be filled in.

Women’s Things

These ethnographic things whose value she helped to enhance were rooted in a view about folklore which Humbert deemed old fashioned: “activity quite suitable for ‘proper ladies’ of average culture” (Humbert, 1937). Tardieu also provided a more concrete account about this view apropos of her field work and the type of people being surveyed, who often were aged persons, “and, as one rather quickly realizes, specifically women.” On the subject of the trousseau and household linen, she wrote that they constitute “‘woman’s national heritage’: she brings it to the marriage; she is its caretaker; she is expected to maintain it in order to be able to hand it down” (Tardieu, 1986). We are still in those years when women’s history was under construction, thanks, in particular, to the work of Yvonne Verdier, who published Façons de dire, façons de faire. In that analysis of the peasant life of women in the heart of the Châtillonnais region, the ethnologist Verdier showed that, while language (regional dialects) played an important role, as one very quickly realized things (utensils, tools) substituted for speech to become a language (Verdier, 1979).

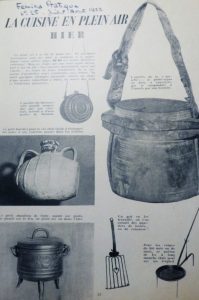

Fig.5. “La cuisine en plein air, hier,” Femina pratique, 25 (July-August 1953). © all rights reserved.

In 1953, Tardieu spoke of the endearing character of these regional objects. Humbert advocated the safeguarding of popular culture. Of course, the actions of these women, and their ways of speaking, were marked by their own subjectivities—which were quite different from someone like an Agnès Humbert, committed to a conscientious Suzanne Tardieu. But, as Daniel Fabre explains, “whatever the case might be, it is the same diffuse sensibility, which is generative of a multiplicity of emotional states; this sensibility is asserted as much in the most dispassionate militant commitments as in the sternest professional calling” (Fabre, 2013). Within a historiographical setting where national heritage was increasingly being grasped as an emotionally-laden place, Humbert and Tardieu could appear as mediators, go-betweens who “take care” of things, with care being understood as a set of practices resting on solicitude, concerned treatment, and responsibility and reliant on two closely correlated constants that one connects rather with the feminine world: the sexual division of labor and its devaluation (Ibos, 2012). In Tardieu’s case, one could even say that a chain of care was set into place, in the sense that these feminine things pass into other hands—the curator’s hands—and are rendered visible, quite specifically, to a feminine readership.

Humbert’s and Tardieu’s professional position ultimately raises the question: Have these women been confined to specific domains, or have they profited from these deserted territories in order to enter into the museum world? Has legitimacy been achieved via “the illegitimate”? To answer these questions, one would have to be able to compare their careers to those of other men and women, though it may already be noted that, while they were quickly able to take on certain responsibilities, they also had to turn toward teaching and guided tours. These associated activities are indeed valued in their profession but can be perceived as auxiliary assignments, supplementary sources of income. Following Michelle Perrot, who encouraged people to ask what a woman’s profession is, it is also fitting to reflect on the type of tasks (mediation, collection, inventorying) that would be more readily to be given to women than to men.

Integrating women into the processes of knowledge acquisition and trying to gauge their action are decisive for a history of forms of knowledge that has long been conceived in their absence. Are women helping to push back the boundaries of scholarly spaces, to strike down some of them, or to produce new ones? It seems to me that, in wanting to restore life to things that have been forgotten because they are deemed unaesthetic, useful, and the product of anonymous generations of people, Humbert and Tardieu illustrate what Bernadette Dufrêne has suggested that one do: begin to reflect on what lesser well known aspects of national heritage owe to the action of women. And on this point, it can be stated that, in endeavoring to reexamine the “silences” in the national heritage, these women also participated in the process of making museums more concerned with these “feminine” things—by forcing museums to become more involved in the social sphere and in society.

Bibliography

Dufrêne, Bernadette. “La place des femmes dans le patrimoine.” Revue française des sciences de l’information et de la communication, 4 (2014). URL: http://rfsic.revues.org/977

Fabre, Daniel. Ed. Émotions patrimoniales. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2013.

Foucher Zarmanian, Charlotte. “Agnès Humbert, historienne de l’art.” Revue de l’Art, 195 (2017): 63-69.

Humbert, Agnès. “L’art dans la vie. Folklore et musée.” Clarté, 8 (March 1937).

Ibos, Caroline. “La mondialisation du care. Délégation des tâches domestiques et rapport de domination.” Métropolitiques, June 2012. URL: http://www.metropolitiques.eu/La-mondialisation-du-care.html

Perrot, Michelle. “Qu’est-ce qu’un métier de femme?” Le Mouvement social, July-September 1987: 3-8.

Tardieu, Suzanne. Les objets domestiques “Foyer-chaleur” des collections du musée des arts et traditions populaires. Dissertation. Paris: École du Louvre, 1945.

_____. “Le trousseau et la ‘grande lessive.’” Ethnologie française, 16:3 (July-September 1986): 281-82.

Verdier, Yvonne. Façons de dire, façons de faire: la laveuse, la couturière, la cuisinière. Paris: Gallimard, 1979.

Weber, Florence. “Politiques du folklore en France (1930-1960).” Pour une histoire des politiques du patrimoine. Eds. Philippe Poirrier, Loïc Vadelorge. Paris: Comité d’histoire du Ministère de la Culture, 2003.

Charlotte Foucher Zarmanian, who has a PhD in Art History, is a Researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) affiliated with the Laboratoire d’Études de Genre et de Sexualité (LEGS, Laboratory for the study of gender and sexuality—UMR 8238). She defended her doctoral dissertation on women artists in Symbolist circles in France, which was published, in the form of an essay, by Mare & Martin in 2015. Her current research investigations bear on the forms of artistic knowledge of women from the eighteenth to the twentieth century.