At the end of his life, Giovanni Battista Piranesi fabricated three large candelabra along with some vases, tripods, and stands out of some mud-covered debris left over from sculptures that had been rediscovered in Hadrian’s villa during the Pantanello excavations of 1769. In retracing the history of these candelabra that no longer evince any of the sobriety of Antiquity or express their original meaning, Caroline Van Eck introduces us to the complicated trajectory of these art objects, starting with the moment of their production and going all the way to their reception. She tests the effectiveness of some anthropological methods of analysis by identifying what pertains to the commodification of art objects and to their singularization.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

'A Neo-Classical Dream and an Archaeologist's Nightmare':

Piranesi's Colossal Candelabra in the Ashmolean Museum

Caroline Van Eck

‘A confused mixture of great part of the finest things of Hadrian’s Villa’[ref]This quotation is from Gavin Hamilton’s account of the excavation at Pantanello: G. J. Hamilton and A. H. Smith, ‘Gavin Hamilton’s Letters to Charles Townley’, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 21 (1901), pp. 306-321.[/ref]

In the last decade of his life, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1779), using the chaotic mass of muddy sculptural débris from Hadrian’s Villa he had found during an excavation in Pantanello near Tivoli in 1769 (fig. 1), made three monumental candelabra.[ref]See Nicholas Penny, Catalogue of European Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum: 1540 to the present day, 3 vols, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992, vol. 1, p. 108-116.[/ref] From these fragments he constructed monumental vases, tripods, pedestals, and not in the last place three monumental candelabra: one, more than 3 meters high, intended for his own grave, now in the Louvre, and two others, slightly smaller but no less intricate, which he sold for the staggering sum of 1000 gold scudi to the British collector Sir Roger Newdigate, which were left to Oxford University. Recently investigated thoroughly and restored, they are now presented as conspicuous, if not typical, cases of the Neo-Classicist revival. Yet on closer scrutiny they turn out to be very mysterious objects indeed, and they have undergone strange reversals of appreciation.

Fig. 1-2 : Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1770-1778), Marble Candelabra, h. 300 cm, made out of various elements (Roman, 15th and 18th Century), after a design by Piranesi. Acquired by Sir Roger Newdigate in 1774, donated to Oxford University in 1775 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum; photo: author).

They conform to the basic scheme of Graeco-Roman candelabra of Hadrian’s age: tall, composite shafts or columns, resting on a pedestal or tripod, and carrying a disc or dish in which wood or incense could be burned (fig. 2). The one on the right in the Ashmolean sports a shaft, surrounded by pelicans with claws that firmly grasp their support as well as attentive beaks. The birds surround a Corinthian floral motif suggestive of a grinning grotesque face (fig. 3). Next comes a young satyr supporting the disc that would hold the light source, doubtless an allusion to the passages in Homer, Plutarch, Pliny or Petronius where slaves acted as living torch-bearers. The one on the left is constructed around a fluted column that is surrounded by three lions biting into their own claws. They carry several levels of reliefs representing instruments of sacrifice as well as mysterious, isolated limbs. Next comes another tripod with reliefs showing three female figures–Pallas Athena, Omphale–and an Amazon. It is crowned by three rams’ heads that serve as the transition to the final part, again a variation on and elaboration of architectural mouldings such as the egg-and-dart list, which are combined with Corinthian acanthus leaves seemingly reaching, in their upward growth, into the culminating disc itself.

Fig. 3. Piranesi Candelabrum in the Ashmolean Museum, showing pelicans flanking ornamentation derived from acanthus leaves and medusa heads (photo: author).

Candelabra are strange objects. Basically they are lamp-stands, tall, composite shafts or columns resting on a pedestal or tripod that supports a disc or dish in which wood or incense could be burned. They are little studied by art historians and archaeologists, in spite of their evident importance in Graeco-Roman culture and its revivals.[ref]H.-U. Cain, Römische Marmorkandelabra (Mainz: Von Zabern, 1985), pp. 5-21; P. Gusman, La Villa Impériale de Tibur (Paris 1904), Chapter 7; E.-Q. Visconti, ‘Le Musée Pie-Clémentin’, in: Oeuvres de Ennius Quirinus Visconti, vol. 4 (Milan: Giegler 1819-22), pp. 31-43 and 305-6.[/ref] Homer already mentions them.

They enjoyed a significant revival during the reign of Hadrian, and examples of very high quality survive from his villa in Tivoli. When these were excavated in the 1750s and 1760s, they were considered so important that creating a proper exhibition space for them was one of the main reasons for founding the Museo Pio-Clementino, which even today boasts a Galleria dei Candelabri.

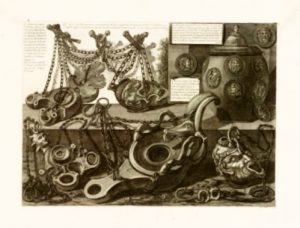

Images of Piranesi’s candelabra were published in 1778 in his Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, a large-format collection of what we would now call Graeco-Roman material culture. This volume showed lamps, altars, vases, lamp-stands, and sarcophagi, in typically Piranesian compositions, or collages, or bricolages, or pastiches even, of very different kinds of objects and fragments. The large majority of them share a funerary context. Somewhat unusually, Piranesi also included objects coming from ethnographical collections, such as the Museo Kircheriano and the Museo Borgiano (fig. 4). His captions indicate that this collection served as a graphic documentation of his attempts to materially reconstruct the funerary culture of the Roman world. In the accompanying texts he argues that in working from the fragments surviving from Pantanello and using Roman composition principles, he is not restoring these ancient objects but reconstructing them entirely in the Roman manner. He is not a restorer of antiquities, but a creator of them.

Fig. 4. Barberini Candelabra, now in the Museo Pio-Clementino, Rome, excavated c. 1650 at the Villa Hadriana, probably made 2nd century AD [photo: James Anderson, c. 1860]

Recent research, however, has shown that 75% of the Oxford candelabra was composed of new material, but Newdigate and his collector friends were unaware of this. Once they were put on display in Oxford they were hailed as original pieces of incomparable quality, ‘the best and most instructive documents of classical sculpture’ the British had ever seen, as one witness put it upon their arrival. Yet less than 30 years later, in the 1810s, they were dismissed by the painter James Barry as total fakes and utter trash.[ref]J. Barry, Works (London 1809), vol. 1, pp. 125-6. See also Henry Blundell, An Account of the Statues, Busts, Bass-Relieves, Cinerary Urns, and other Ancient Marbles, and Paintings, at Ince (Liverpool: J. McCreery, 1803), p. 174.[/ref] That is, from a major document of the ongoing material presence of Roman art, and a showpiece of classical sculpture, they were turned into mere documents in the history of archaeology and collecting.

By focusing on the radical change in appreciation of the candelabra and offering one partial explanation for it, I hope to look with fresh eyes upon a set of phenomena–usually connected with Neo-Classicism–that have become so familiar as set pieces of Western artistic and museum culture that we have forgotten how strange they really are.

Lamp Lore in Antiquity

Roman candelabra are just as little studied as their 18th-century descendants, since like the large majority of Roman or Greek precious or luxury objects of interior design, they have suffered from a bad press started by Pliny and his prejudices against luxury, and this has endured to the present day. Also, candelabra, like many Graeco-Roman lamps, do not have a stable iconography, conveniently linked to their function or use. Despite their material solidity they are what one might call socially and even ontologically unstable objects.

From the earliest documentations of their presence, in Homer for instance, they have a double role and a dubious nature. In Homer’s Odyssey, wooden or bronze candelabra are linked to the custom of having slaves hold up lamps during festive banquets, and this association would continue to be evoked or revived throughout Antiquity. But they also had a religious role, either as votive gifts or as instruments of ritual illumination–even today archaeologists do not agree. The funerary role Piranesi gave them is not attested. Surviving sources mention how these objects, which by the first century BC had grown into a major category of what we would now call the luxury industry, had moved away from their religious contexts, in which they would flank statues of divinities and illuminate temples, to become the illuminators of the homes of the very rich. The sources also speak of material excess, erotic associations and intense engagements, if not identifications of humans with them.

Pliny offers a tale about a Roman patrician lady who paid the staggering sum of 50.000 sestertii for a particularly fine candelabrum because it combined the excellence of the two major workshops at the time, Aegina, which specialized in sockets, whereas Tarentum was the place to go to for the branches.[ref]Pliny, Historia Naturalis, XXXIV.vi.12[/ref] At the sale, a slave was thrown in, who had to perform naked for her during the banquets illuminated by this candelabrum. The lady appreciated his charms so much that she began an affair with him, eventually leaving him her entire estate in her will. After her death the slave, now a rich man, revered the candelabrum like a god, or indeed numinum vice, instead of the gods.

There is, however, yet another aspect to the ill-defined ontological status of candelabra in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Like most lamps, they were considered capable of movement and animation and thought to witness the acts they illuminated. Ruth Bielfeldt has recently argued that these claims are not as ill-founded or counter-intuitive as they might seem when considered in the context of classical theories of visual perception.[ref]Ruth Bielfeldt, ‘Lichtblicke – Sehstrahlen. Zur Präsenz römischer Figuren- und Bildlampen’, in idem (ed.), Ding und Mensch. Gegenwart und Vergegenwärtigung in der Antike, Heidelberg 2014, pp. 169-238[/ref] They are capable of sight like humans and animals because their very action, to cast light, is so very similar to the way sight was thought to work: by the active emission of particles that touch, and are bounced back by, the objects they reach.[ref]Bielfeldt 2014, p. 204.[/ref] This lore is wittily summarized in Lucian’s science-fiction tale The True History, where one episode takes place on a planet called Lychnopolis or Lamp Town:

On landing, we did not find any men at all, but a lot of lamps running about and loitering in the public square and at the harbour. Some of them were small and poor, so to speak: a few, being great and powerful, were very splendid and conspicuous. Each of them has his own house, or sconce […]. They have a public building in the centre of the city, where their magistrate sits all night and calls each of them by name, and whoever does not answer is sentenced to death for deserting. They are executed by being put out. We were at court, saw what went on, and heard the lamps defend themselves and tell why they came late. There I recognised our own lamp: I spoke to him and enquired how things were at home, and he told me all about them.[ref]Lucian, True History I.29, Loeb ed A.M. Harmon, 1913, vol. I, p. 283.[/ref]

Fig. 5. Piranèse, Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, planche 11 : lampes et vase avec camées, Rome, 1771. Photographie : Getty research Centre

Very often Graeco-Roman lamps play in their design on the similarity between giving light and seeing. There are many examples–some of which are included in Piranesi’s Vasi, Candelabri e Cippi–where the openings for candle wicks have the shape of a human being’s face (fig. 5). The motif of the lucerna viva, the living lamp, is a frequent topos in Greek and Roman poetry; also, the term rostrum, snout or beak, is used for animals, persons or objects with a beak-like appearance, such as lamps. The conscious lamp, a witness of the acts it illuminates, is a recurring theme in erotic poetry. Thus in Lucian’s Cataplus, the lamp is so horrified by what it has to witness in the bedroom where it stands that it tries to extinguish itself by refusing to drink its lamp oil. Lamps thus are witnesses, aware of what goes on in front of them and are therefore literally conscious.[ref]Bielfeldt 2014, pp. 209-14, with many references to Greek and Latin texts.[/ref]

Piranesi’s Transformation of His Discoveries at Pantanello

Now, when we place Piranesi’s candelabra next to those surviving from Roman antiquity, which he knew very well, it is striking to see how very different the ones he made are. Compared to their clearly visible structure with pedestal, shaft and light-bearing disc very much derived from acanthus and Corinthian forms, and quite sober iconography of gods and small erotes, his work presents a very riot of ornament, a profusion of elements taken from altars, the theatre, sarcophagi, and furniture, and exhibits a tendency to duplicate and reverse classical motifs: in his candelabra, the lions’ claws are not simply content to carry a pedestal, but, when doing so, enliven their performance of this task by sinking their teeth into their own claws. Next to this profusion of ornament and riot of allusions, we find some striking cases of the lamp lore listed by Bielfeldt: animation, in many of the animals’ heads and faces; movement; an inwardness that suggests consciousness in the elephants’ heads; and intense observation in the pelicans and eagles. All this would be much more evident were we able to see the candelabra in action, carrying their discs of light in dark spaces lit by other flickering lights.[ref]R. Bielfeldt, ‘The Lure and Loss of Light: Roman lamps in the Harvard Art Museum’, in S. Ebbinghaus (ed.), Ancient Bronzes through a Modern Lens. Introductory Essays on the Study of Mediterranean and Near-Eastern Bronzes, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museum 2014, pp. 171-93, this passage p. 189; see also Goethe, Italian Journey, March 3, 1787.[/ref] One of the few things Piranesi said about the candelabrum intended for his own tomb concerned the light itself: an eternal flame was to burn on the antique candelabrum meant to be placed on his tomb–a candelabrum that was in fact his own creation.[ref]G.B. Piranesi, Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, caption to Plate 107.[/ref]

In Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, lamps are frequently depicted, from the candelabra in the frontispiece of Part One to the numerous small lamps in the shape of humans and animals, often grotesquely contorted, exotic or grotesque; and this is again the case in the series of monumental plates of the candelabra for Newdigate and for his own grave, the latter now in the Louvre. The provenance of some of these lamps is revealing: they were all excavated in Rome, but they may have been made all over the Roman Empire, and Piranesi saw them in the ethnographical collections of the Museo Borgiano and the Museo Kircheriano. This suggests that for him, the candelabra were not only very fine specimens of Roman artistry but also what we would now call material culture: objects documenting the life and rituals of the Graeco-Roman world.

The Biography of Objects

All this suggests a few clues for understanding the drastic devaluation of these candelabra. Despite Piranesi’s claims to the contrary, they do not look at all like surviving specimens from Hadrian’s time; their composition, structure, ornament, iconography, and function are different, and they exhibit a design overdrive we do not find there. Also, the Graeco-Roman cultural meanings associated with candelabra are very different from 18th-century ones. Instead of the dominant funereal and Christian connotations of the extinction of mortal light and the endurance of the lux aeterna, we find a fascinating range of statements about sight, animation, attentiveness and witnessing. Graeco-Roman lamps often take human or animal shapes, and Piranesi’s candelabra are an excessive culmination of this trend. These meanings seem to have dropped completely from sight in their reception in the 18th and 19th centuries, as is shown by Visconti’s accounts of the specimens in the Sala dei Candelabri and the Louvre candelabrum. They concentrate entirely on provenance and conventional iconographic analysis.

In the third place, Piranesi places himself squarely within the tradition of Roman workmanship and artistry, but his notion of authenticity is very different from the one that would emerge around 1800. What he actually did was use fragments found in Pantanello and other collections and employ them as the elements out of which he would create his entirely new compositions. Since he presents them as Roman antiquities, for us this makes them fakes or even forgeries. But Piranesi himself adopted the attitude that, since he understood Roman design methods, materials and craftsmanship as nobody else did at the time on account of his intense and longstanding first-hand experience as an excavator and draughtsman, he was in fact continuing Roman traditions of craftsmanship. Such an attitude toward authenticity was very much on its way out by the end of the 18th century because of Winckelmann’s effort to provide a chronology of Graeco-Roman art and the growing awareness that many classical statues were not Greek but Roman copies, an insight that resulted from the geologist Dolomieu’s investigations into the properties of various marble varieties available in Italy.

So a profound shift occurred in the appreciation of both the meaning and the status of Piranesi’s candelabra. This is not an isolated case but a symptom, I would argue, of the great changes that had taken place from 1760 to 1800 in the way Graeco-Roman art was viewed and appreciated. As is already evident from the reactions at the time to Piranesi’s polemic with Julien David Leroy, Laugier and Mariette about the origins of architecture and the nature of ornament, he was fighting a losing battle. His arguments in the Parere and the Diverse Maniere in favour of stylistic diversity, variety, richness and complexity, and his view of creativity that went beyond faithful imitation of the Ancients were rendered obsolete by the success of Winckelmann’s clear model of a history of ancient art and by his aesthetic that privileged simplicity and transparency. While Winckelmann’s beauty resembles pure water, Piranesi’s is more like a Barolo wine, with its complex and contradictory layers of murky tar flavours and flowery violet fragrance.

Yet there is also another, less narrowly art-historical way of understanding the change in appreciation of the candelabra. The events of their lives resonate very strongly with present-day debates about the biographies of objects or the social life of things. Appadurai argued in his The Social Life of Things for a methodological fetishism, thereby turning commodity fetishism inside out. Instead of going along with a traditional view of mystification or reification of commodities, as if they possessed autonomous lives of their own in the market, Appidurai assumes things have lives. Following their movements, he thus retraces how human beings endow objects with value across a variety of contexts. Now, this becomes really interesting for us the moment things–or human beings, for that matter–refuse to remain in their normal domain: in the case of objects when they are endowed with agency or life, or in the case of humans when they are treated as objects. Two processes cross paths in such situations: what the anthropologist Kopytoff called commodification, a homogenising process through which objects end up as commodities on the market and are subjected to the laws of value determination through the forces of demand and supply; and its opposite, singularisation, through which objects are singled out, set apart from the realm of commodities.[ref]Kopytoff, I., ‘The Cultural Biography of Things. Commoditization as Process, in A. Appadurai (ed.), The Social Life of Things. Commodities in cultural perspective (Cambridge 1986), 64-91.[/ref] The Oxford candelabra clearly went through both stages; their ancestors in late Republican Rome, as Cicero tells us, started life as sacred objects only to end up as fetishes in a collector’s home; but after their excavation in the 17th and 18th centuries, they went through an accelerated process of commodification, entering the Roman art market through the agency of Piranesi, Cavaceppi, and dealers such as Jenkins, followed by a new phase of singularisation, when they were given by Newdigate to Oxford University, only to end up in the Louvre, or in the Museo Pio-Clementino, that is, in a museum setting, withdrawn from commercial circulation.

Bibliography

BRAUN, Emil. Die Ruinen und Museen Roms. Für Reisende, Künstler und Althertumsfreunde. Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1854. pp. 346-50, 472, 476, 485-86, and 491.

BIELFELDT, Ruth. “Lichtblicke – Sehstrahlen. Zur Präsenz römischer Figuren- und Bildlampen”. In Ding und Mensch. Gegenwart und Vergegenwärtigung in der Antike. Ed. Ruth Bielfeldt. Heidelberg: Winter, 2014. Pp. 169-238.

GRIENER, Pascal. “Plaster versus Marble: Wilhelm & Caroline von Humboldt and the Agency of Antique Sculpture”. In Idols and Museum Pieces. The Nature of Sculpture, its Historiography and Exhibition History, 1640-1880. Ed. Caroline A. van Eck. Munich and Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017. Pp. 159-177.

HAMILTON, G. J., and A. H. SMITH, “Gavin Hamilton’s Letters to Charles Townley”. The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 21 (1901): 306-321.

KOPYTOFF, Igor. “The Cultural Biography of Things. Commoditization as Process”. In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986. Pp. 64-91.

PENNY, Nicholas. Catalogue of European Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum: 1540 to the Present Day. 3 vols. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1992. Vol. 1. Pp. 108-116.

PIRANESI, Giovanni Battista. Vasi, candelabri, cippi, sarcofagi, tripodi, lucerne ed ornamenti antichi, disegni ed incisi dal cav. Gio. Batta. Piranesi, pubblicati l’anno 1778, 2 vols, S. l. [Roma], no date [1778].

PIRANESI, Giambattista. Diverse maniere d’adornare i cammini ed ogni altra parte degli edifizij. Rome: Stamperia Generoso Salomoni, 1769. Reprinted in Giovanni Battista Piranesi, The Polemical Works, Rome, 1757, 1761, 1765, 1769. Ed. John Wilton-Ely. Farnborough, Hants: Gregg International Publishers Ltd, 1972.

VAN ECK, Caroline A., and M. J. VERSLUYS, “The Hôtel de Beauharnais in Paris: Egypt, Rome, and the Dynamics of Cultural Transformation”. In Housing the Romans. Ed. Katherine T. von Stackelberg and Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

VISCONTI, E.-Q. “Le Musée Pie-Clémentin”. In Oeuvres de Ennius Quirinus Visconti. Vol. 4. Milan: Giegler, 1819-22. pp. 31-43 and 305-306.

A former student at the Ecole du Louvre, Caroline van Eck is a Professor of Art History at Cambridge. In 2017 she holds the Slade Chair in Fine Art at the university of Oxford. Recentely, she published : Art, Agency and Living Presence. From the Animated Image to the Excessive Object (Munich, de Gruyter, 2015) ; François Lemée et la statue de Louis XIV sur la Place des Victoires : les débuts d’une réflexion ethnographique et esthétique sur le fétichisme (Paris, Centre Allemand d’histoire de l’art/Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2013) ; « Art Works that Refuse to Behave : Agency, Excess and Material Presence », in Canova and Manet, New Literary History, October 2015 ; and, with Miguel John Versluys et Pieter ter Keurs, « The Lives of Styles. Objects, Agency and Cultural Memory », Cahiers de l’Ecole du Louvre, vol. 7/1, 2015.