In drawing up an inventory of images and things in the nineteenth century, Manuel Charpy shows us how bourgeois domestic interiors ended up resembling still lifes, with curios, assembled in a certain order, accumulating there as within a picture. A painted or photographic portrait of a collector was, in this regard, edifying: his acquisitions were set off and highlighted, as in a museum. Here, as elsewhere, it was the artist himself who set the tone with his more or less exotic studio—a kind of picturesque inventory of objects but also similar to an antique shop, since objects were sold there, too. The painter was then set forth as an example of good decorative taste, a characteristic he shared with the interior decorator, that other theater director of bourgeois life.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Canvas, Studio, and Apartment:

Still Lifes of Objects and Still Lifes in Images

in the Nineteenth Century

Manuel Charpy

The still life was a genre that was savored in nineteenth-century middle-class [bourgeois] domestic interiors. Yet, still more than that, domestic interiors in their entirety resembled still lifes, accumulations of curios staged in such a way as to be evocative of the pictorial tradition in art. Cardboard or wax accessories, like fruits, bespoke the blurring between domestic decors and fictions. A new economy of images was at work in this bourgeois act of transubstantiation: while copies of images were proliferating and migrating about as never before,[ref]Michel Foucault, “Photogenic Painting,” in Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, Gérard Fromanger: Photogenic Painting, ed. Sarah Wilson and trans. Dafydd Roberts (London: Black Dog, 1999).[/ref] pictures, studios, and domestic interiors became increasingly confused with one another. In a liberalized art market, painters and interior decorators took charge of tidying things up and engaged in the trade in things for a clientele in search of good taste.

The Art of the Propmaster

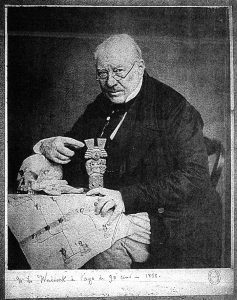

Fig. 1 Portrait of the antique dealer, painter, and collector Jean-Frédéric Waldeck with his Mexican objects. 1858. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Boban Collection, NAF 21478

Within the domestic landscape, which mixed real, fictive, and painted objects, there was, alongside the sale of old paintings, a thriving business in “furniture painting” (to paraphrase Erik Satie’s expression furniture music), copies of which were churned out in assembly-line fashion and sold, at prices fixed according to the size of the canvas and the “richness” of the frame, in print shops as well as in department stores. Yet painting also pertains to the realm of the unique: the portrait of the collector surrounded by his booty remained a hardy sales item, a prolongation of the portrait of the eighteenth-century art lover. Photography democratized this practice. The antiques dealer and dealer in curios Eugène Boban received hundreds of portraits of collectors sitting imposingly amid their finds (fig. 1).[ref]Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Boban Collection, NAF 21476-21478, and Hispanic Society of America (New York), boxes II-III.[/ref] Bought together, they constitute a portrait on their own. Some painters specialized in this field—like Blaise Desgoffes, who, between 1860 and 1900, applied himself to “the meticulously exact reproduction of the objets d’art and furnishings” of collectors.[ref]Gustave Vapereau, Dictionnaire universel des contemporains . . . (Paris: Hachette, 1865).[/ref] Some waxed ironic about these “propmasters [ustensiliers] . . . who make pictures with a gorgerin, a ewer, and a precious box of some sort.”[ref]“Accessoires,” in Joséphin Peladan, La décadence esthétique. L’art ochlocratique, salons de 1882 (Paris: Dentu, 1883).[/ref]

Fig. 2 “Coin mexicain” (Mexican corner), in Eugène Boban’s store, ca. 1870. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Boban Collection, NAF 21478

Yet the middle classes became Desgoffes’s champions: “We find it in good taste now to heap scorn on the marvels he executes,” but the pictures of an “ivory bust belonging to one of the most enlightened lovers of art” and of a “pure quartz vase from the fourteenth century are two precious jewels over which the museums of Europe one day will vie.”[ref]Ernest Chesneau, L’art et les artistes modernes en France et en Angleterre (Paris: Didier, 1864), pp. 264-65.[/ref]

In the hopes of figuring in scholarly imprints or even in popular illustrated publications, to accompany articles on art history and travelogues, numerous collectors had prints of their masterpieces made by such engravers as Alfred Darcel and Henri Guérard. Moreover, such images were used to illustrate the sales catalogues that began appearing in large numbers in 1860.[ref]Archives de Paris [hereafter: AP], auction catalogues, D1E3ff.[/ref] Here again, photography came to democratize this practice, dealers having their merchandise photographed for advertising purposes or in order to sell these visual documents to painters and furniture makers (fig. 2).[ref]Boban Collection, AN, 613 AP, Warneck and Sambon, Antiques Dealers, and the Soubrier Company’s Private Archives [stored at the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris].[/ref] In their wake, collectors had their even modest collections photographed by studios well versed in the composition of still lifes.

At the Headwaters of Painting

Alongside the “propmasters/set designers,” a kind of painting thrived on the art of composing images of antiques and curios around a motif. For, there were painters, along with writers, who invented such objects. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc recalled painters who, in the 1840s, sought “to give to their historical works a cachet of truth, [of] local color,” by accumulating antiques.[ref]Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l’époque carlovingienne à la Renaissance (Paris: Bance, 1858), p. 296.[/ref] This “picturesque artist’s thrift store” became a cliché.[ref]“Atelier,” Dictionnaire de la conversation (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1858), and Philippe Burty, “L’atelier de Madame O’Connell,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1860-1861: 350-51.[/ref] The fashion for Orientalism introduced into studios, as well as into paintings, some souvenirs from voyages to the Orient and North Africa.

Fig. 3 Studio of the painter Pierre-Jules Jollivet on the Rue des Saints-Pères, in Edmond Texier, Tableau de Paris, vol. 2 (Paris: Paulin et Le Chevalier, 1853) ©Manuel Charpy

Alexandre Dumas described Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps’s studio, where “Algerian slippers” accumulated like “Ganges idols.” “You think you’re entering the home of an artist,” he said in conclusion, “and you find yourself in the middle of a museum.”[ref]L’Artiste, April 1, 1852: 73-74.[/ref] Antiquing became a part of the creative process. Studios and then paintings exhibited these “finds,” like Eugène Fromentin’s in Algeria and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant’s in Morocco.[ref]Charles Gueulette, “Eugène Fromentin,” in Les ateliers de peinture en 1864, visite aux artistes (Paris: Castel, 1864), and John Shirley Fox, Reminiscences (London: Fox, 1909), pp. 204-206.[/ref] A divided Paul Eudel noted, after his visit to the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme: “What a charming domestic interior! You find here the same attention to detail, the same search for perfection as is found in his pictures.”[ref]Paul Eudel, “Léon Gérôme,” in L’hôtel Drouot et la curiosité en 1886-1887 (Paris: Charpentier, 1888).[/ref] Painters set themselves up as inventors of objects—even though the majority of them provisioned themselves at antique dealers. In artists’ studios, members of the bourgeoisie acquired together a taste for curios and knickknacks.

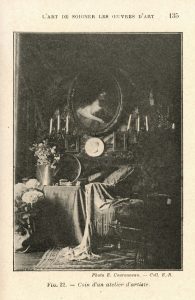

Fig. 4 Émile Bayard, L’Art de soigner les œuvres (Paris: Ernest Gründ, 1928 [drafted before the War])

Still rare in middle-class domestic interiors at the time, these antiques and curios charmed people in artists’ studios. In the late 1860s, Nestor Roqueplan noted the passage of the “debris of time past” from those studios to “society people [for] the everyday furnishing” of their homes.[ref]Nestor Roqueplan, La Vie parisienne (Paris: Lévy, 1869), pp. 161-65.[/ref] The same movement took place in the case of exotic objects. The Japonism invented by a painter “strolling [flânant] about the store of a dealer in Far-East curios” reached artists’ studios and then “the crowd of art lovers.”[ref]Ernest Chesneau, “Le Japon à Paris,” in Gazette des Beaux-Arts, September 1878: 385-97.[/ref] Rustic objects themselves became attractive when they went into the studios of Rosa Bonheur and Fromentin. The pictures that came out of those studios were like inventories, highly prized by the middle classes.

Whence the success of studio visits. Long considered places not to be frequented, artists’ studios were opened to the public and visits became a bourgeois pastime, recommended by guidebooks (fig. 3).[ref]Albert Wolff, La Capitale de l’art (Paris: Victor-Havard, 1886), pp. 285-90, and Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Thibault Collection, Print Room, Li243; “Ateliers de peintres connus,” in Paris-Parisien 1898 … (Paris: Ollendorff, 1898), pp. 88-90, and Usages mondains: guide du savoir-vivre moderne dans toutes les circonstances de la vie (Paris: Victor-Havard, 1901), p. 455.[/ref] One observed the pictures present there but also the seductive shambles of the creative life. Built in the style of conservatories, the glass roofs of studios acclimated curios to Parisian apartments. “Picturesque hodgepodges,” with their learned sense of order, became models of interior decorating for a bourgeoisie burdened with the clutter of sundry objects. Artists’ studios, noted Hippolyte Taine, were “invented” domestic interiors; “they are not the middling work of interior decorators.”[ref]Hippolyte Taine, Notes sur Paris. Vie et opinions de M. Frédéric Thomas Graindorge . . . (Paris: Hachette, 1857), p. 247.[/ref] And Henry Havard confirmed that a “deliberate disorder generally accentuates the picturesque character of the decorations.”[ref]Henry Havard, L’Art dans la maison, Grammaire de l’ameublement (Paris: Rouveyre, 1885), chapter XLVIII.[/ref] To guard against errors in taste and to ward off petit-bourgeois order, the guidebooks recommended one follow the “advice of artists” and gave, as models to be followed, the “recesses of artists’ studios” (fig. 4).

Staged Objects

Curios also began to accumulate on theatrical stages. That was the case in such exotic fantasies as La Vénus noire (1879), where an “African museum” was exhibited in the foyer of the Théâtre du Châtelet.[ref]Adolphe Belot, Catalogue du musée africain installé au foyer du théâtre du Châtelet pour les représentations de la Vénus noire, voyage dans l’Afrique centrale, pièce nouvelle en 5 actes et 12 tableaux (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1879).[/ref]

Fig. 5 “Magasin des accessoires” (accessories store), Jean-Pierre Moynet, L’envers du théâtre: machines et décorations (Paris: Hachette, 1873), p. 166 ©Manuel Charpy

Those objects conferred a realism upon the plays, and in return they seemed to be coming to life again in their original environment. Historical plays themselves promoted antiques. In the late 1840s, one witnessed the concomitant return of Marivaudages, “eighteenth-century painters,” and Rococo knickknacks.”[ref]Francisque Sarcey, Quarante ans de théâtre: feuilletons dramatiques (Paris: Bibliothèques des Annales, 1900), vol. 2, p. 207.[/ref] That is how Arnold Mortier described the decor of La Duchesse Martin: “everywhere, old knickknacks, stoneware filled with flowers, hammered copper objects, used sideboards, and Louis XV clocks purchased at insane prices.”[ref]Arnold Mortier, “16 mai,” Soirées parisiennes . . . (Paris: Dentu, 1884).[/ref] And apropos of Balsamo, he noted that the Director of the Odéon Theater “savored the effect” of his “second-hand period pieces,” hunted down at the most unlikely dealers’ shops, . . . and he feels, quite naturally, this evening, the sweet emotions of a collector totally consumed by his quest.”[ref]Ibid., 1878.[/ref] In short: historical reconstruction and chasing after trinkets, rolled into one (fig. 5).

Yet, while the majority of plays were mirrors held up to private bourgeois life, the accessories became real. In 1859, Louis Ulbach could write: “One must first of all please a society that asks about its own secrets by presenting an accurate horizon of the milieu in which it bustles about.”[ref]Louis Ulbach, “L’art au théâtre,” in La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1859: 34.[/ref] Consequently, “the set designer and the theater director have turned themselves into interior decorators and “salesmen of knickknacks.”[ref]Louis Becq de Fouquières, L’art de la mise en scène, essai d’esthétique théâtrale (Paris: Charpentier, 1884), p. 78.[/ref] The interior decorators, those new “theater directors of bourgeois life,” provided furniture pieces and curios. From Dumas to Georges Feydeau, the stage directions of the time specified the style, age, and placement of the furniture and knickknacks, down to what colors they should be. Opera glasses ensured that the audience could scrutinize the objects on stage, in the manner of painting enthusiasts. The influence of these decors was all the stronger as theater reviewers would linger over them, sustained as they were by photographs that often included views of the bare decor.

Exiting the theater, the middle classes found these objects again in store windows or at the Drouot auction house. The advertising power of the process was such that dealers took the stage themselves, some going so far as to put on plays—like the interior decorator Jules Duval, who turned himself into an author in order to parade his compositions across the stage.[ref]Jules Duval, Le Marchand de son honneur, Théâtre de Cluny, April 20, 1881.[/ref]

Painters & Co.

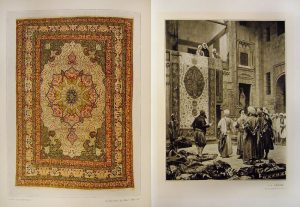

Fig. 6 “L’Orient par J. L. Gérôme, offert par les Grands Magasins du Bon Marché, Paris aux visiteurs du salon des artistes français,” Bon Marché catalogue, 1910. Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, “Actualités” series: “Grands magasins.”

The nature of this association between artists, stages opened to a select audience, and the knickknack business was the same in the world of painters. While dealers were setting up shops in the vicinity of painters in order to attract a middle-class clientele,[ref]AP, D11U3/187, bankruptcy 111942, Latapie curio dealer, rue de Rivoli, 1854.[/ref] painters were exhibiting and selling antiques and curios. This was the case with Jean-Paul Laurens, who bought or borrowed, at Boban’s, the curios that abounded in his studios as well as in his pictures.[ref]Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Boban Collection, NAF 21478, Letters, nos. 87ff., and Jules Claretie, Peintres et sculpteurs contemporains (Paris: Jouaust, 1884), p. 273.[/ref] In return, when the play Derniers moments de Maximilien met with success, Boban placed these objects in his shop window. Such combinations became common after 1890: antique dealers left objects to be sold at the studios and homes of painters, and painters exhibited their works in the shops of antique dealers. Large department stores did the same thing—like Le Bon Marché, which reproduced pictures by Gérôme in which clients could see Oriental rugs on sale at the store (fig. 6).[ref]“L’Orient par J. L. Gérôme, offert par les Grands Magasins du Bon Marché, aux visiteurs du salon des artistes français” (The Orient, by Jean-Léon Gérôme, offered by the Bon Marché Department Store to visitors of the Salon of French Artists), 1910.[/ref]

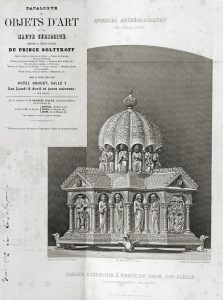

Fig. 7 “Quarter-sized” engraving of a Byzantine shrine from the collection of Prince Soltykoff, published in the Annales archéologiques and reproduced in the Prince Soltykoff auction sale catalogue, April 8, 1861, under the supervision of Charles Pillet.

This logic became pronounced as early as the 1850s, with the opening of Drouot, a space for the art business, and the sales of “studio objects” (fig. 7). In 1853, the sale organized by Decamps proved quite popular, with the middle classes carrying away yatagan swords and “sixteenth-century goblets.”[ref]AP, D42E3/26, Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps sale, April 21-23, 1853; Catalogue des tableaux, dessins, armes, meubles, costumes composant l’atelier de M. Decamps . . . , 1853, and Félix Mornand, La vie de Paris (Paris: Librairie Nouvelle, 1855), p. 118.[/ref] In 1860, at the time of his death, people were desperate to get ahold of his drawings and his “tremendous collection of objets d’art and curios.”[ref]Philippe Burty, Gazette des beaux-arts, December 1860: 317.[/ref] The number of sales for studio objects exploded.[ref]AP, D42E3/40-49.[/ref] Reviewers stuck to obituaries, society columns, and furniture catalogues. During the Vibert auction in 1887, the public was keen on purchasing objects “that served to decorate the artist’s house as much as they provided the information the artist needed to execute his works” (fig. 8).[ref]Paul Eudel, L’Hôtel Drouot et la curiosité en 1887 (Paris: Charpentier, 1888), pp. 181-82.[/ref] Eudel saw in such “studio debris” the “decors of a theater” that one can make out to be social in character.[ref]Ibid., 1881, p. 343.[/ref] After 1890, not only did painters organize sales but such sales often offered only “studio utensils” along with exotic and antique objects.[ref]AP, D1E23-68, sales records of the Compagnie des Commissaires-priseurs (Company of Auctioneers), 1890-1914, and Catalogue des objets d’art et de curiosité, [et] ustensiles d’atelier garnissant l’atelier de feu M. Brissot de Warville, Drouot, salle 3, les 14 et 15 novembre 1892, 1892.[/ref] These sales were all the more successful as they took place in studios where visits and knickknack-hunting had become synonymous.

Waxing ironic, Louis-Edmond Duranty noted in 1882: “We know of painters who have at their homes some 30,000 francs worth of knickknacks. . . . Costumes, furniture, tapestries, weapons—they paint them in their pictures, thereby attracting the eye of the art lover. Without their knickknacks, they would not do a quarter of the business they do.”[ref]Louis-Edmond Duranty, Le pays des arts (Paris: Charpentier, 1881), pp. 140-41.[/ref] This practice was commonplace. The “ethnographic painter” Théodore Delamare, who depicted everyday Chinese life without having ever left Europe, sold the pottery presented in his pictures.[ref]Charles Gueulette, “Théodore Delamare, 4 janvier 1864,” in Les ateliers de peinture en 1864.[/ref]

Fig. 8 : Jehan Georges Vibert, Le Comité des œuvres morales, oil on canvas, 1866, private collection. This painter also executed several Vendeurs de tapis (rug sellers)

That was also the case with Jehan Georges Vibert, who sold at auction the large Chinese vases, objects from Brittany, Turkish rugs, and eighteenth-century furniture pieces that populated his paintings.[ref]AP, D48E3/74, Me Chevallier, Catalogue des tableaux, études composant l’atelier de J. G. Vibert […] et du mobilier garnissant son hôtel, Drouot, 21-28 avril 1887, and “La vente Vibert,” Le Bulletin de l’art ancien et moderne, April 1887.[/ref] Pictures became catalogues, inasmuch as they were reproduced by the printing process.[ref]See the Goupil and Co. archives (Bordeaux) and Stephen Bann, Parallel Lines: Printmakers, Painters and Photographers in Nineteenth-Century France (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001).[/ref] In a dizzying way, objects circulated from studios to domestic interiors that imitated paintings of domestic interiors executed on the basis of objects accumulated in studios. . . . With life imitating art, the bourgeoisie bought what it had already seen.

Within this context, numerous painters passed over to the other side of the looking glass in order to become interior decorators or dealers in curios—like the antiques dealer Charles de la Roche, a former painter at the French War Ministry.[ref]Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris, “Actualités” series: “Antiquaires” and “Tapissiers,” and AP, D11U3/639 1869, Charles de la Roche, dealer in curios, 7 rue Bonaparte.[/ref] This transition seemed natural. A large number of art experts also were former painters, often of still lifes, like the emblematic Jules Féral.[ref]See, for example, L’heure du thé, 1858, and AP, D4E3 43/59 (1876), 64 (1882), and 75 (1890).[/ref] An “artist painter” like Lucas-Moréno sold at the same time “old paintings, antiques, [and] curios” in his studio-boutique on the Rue de Provence. An object purchased from a painter took on a picturesque and Romantic veneer, gave one the feeling of having escaped from the standardized taste of the large department stores, and extracted itself from the commercial realm of ordinary mortals.

Bibliography

CHARPY, Manuel. “Les ateliers d’artistes et leurs voisinages. Espaces et scènes urbaines des modes bourgeoises à Paris entre 1830-1914.” Revue d’histoire urbaine, 3 (2009).

_____. “Le spectacle de la marchandise. Sorties au théâtre et phénomènes de mode à Paris, Londres et New York dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle.” Pascale Goetschel and Jean-Claude Yon. Eds. Au théâtre! La sortie au spectacle, XIXe-XXIe siècles. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 2014.

_____. “L’ordre des choses. Sur quelques traits de la culture matérielle bourgeoise parisienne, 1830-1914.” Revue d’histoire du XIXe siècle, 1 (2007).

GUICHARD, Charlotte. Les amateurs d’Art à Paris au XVIIIe siècle. Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2008.

MARTIN-FUGIER, Anne. La Vie d’artistes au XIXe siècle. Paris: Fayard, 2007.

MILNER, John. Ateliers d’artistes: Paris, capitale des arts à la fin du XIXe siècle. Paris: Du May, 1990.

Manuel Charpy is a research fellow at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and is connected with the University of Lille. He works on the history of material culture and the history of social, political, and cultural identities in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries in Europe, the United States, and Sub-Saharan Africa. His work bears in particular on the production of clothing, clothing in colonial settings, the birth of the market in antiques and exotic curios, and the social practices of portraiture. Since its inception, he directs Modes pratiques. Revue d’histoire du vêtement et de la mode.