Long neglected, animals have once again, especially since the 1980s, been placed at the center of contemporary art. Against all expectations, animals serve less the cause of ecology than to reassure humans of their own status, as we are told by Marion Duquerroy, whose dissertation on this subject will be published by Presses du Réel. The history of animal embalming and then of their naturalization and their placement under glass says more about us than about them; the same goes for the widespread craze of cutting creatures up into pieces (“botched taxidermy,” to use Steve Barker’s expression).

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Marion DuquerroyFlesh, hairs, and feathers: animals as objects in contemporary art

For a few years now, and after having been largely forgotten by avant-garde movements, animals are again taking front stage on the arts scene. In the so-called postmodern era, they are being accorded a major place within the world of artistic creativity, and within this world, the English-speaking countries, including Great Britain, are not to be outdone. Nevertheless, one should not be mistaken about what is going on: these animals, thus aestheticized, are not always there to serve the cause of ecology but become to a greater degree things that have a lot to say about man and about the current situation in which he is set.

Damien Hirst & Co.

In 1991, Damien Hirst, the leader of the Freeze generation, brought out onto the arts scene his tiger shark preserved in a giant formaldehyde-filled aquarium. It would not be an exaggeration to say that this work provoked as much astonishment as it did indignation. Both these reactions stem, on the one hand, from the fact that the animal figure is preserved here physically intact as a work of art, thereby raising the question of what can or cannot constitute a work of art, and, on the other hand, from the issue raised as to the legitimacy of appealing to animal rights.

Hirst incontestably remains, beyond this polemic, the most highly mentioned artist when it comes to the question of inserting animals into contemporary art. Indeed, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living is the first work of this type to appear in a museum space, during the 1997 Sensation show at the Royal Academy. A near-complete Noah’s Ark, with pigs, sheep, cows, and doves, would follow thereafter.

The breed of shark Hirst presented is classified among the most dangerous species for man, right behind the great white shark. Hirst’s choice was not innocuous. Weightlessly suspended, the beast seems to be heading straight at us, fixing its gaze upon us with its small dark eyes and revealing to us its powerful jaws. We are forced to note that it is in no way there to be admired but is there, instead, to bring out our fears, calling up our literary and cinematographic memories, which transform it into an inveterate flesh eater, as in the film Jaws (1975), where it plays the hero’s role. In sum, the work speaks of everything except the animal itself. In 2005, John Isaacs also exhibited a shark, this time epitomized merely by its fin. The sculpture in resin, Everyone’s Talking about Jesus, shows us its pointy dorsal fin cut directly from its flesh, which suffices for one to understand what is at issue. Who has not already imitated this predator by raising his hand onto the top of his head?

Just like Hirst, Isaacs makes use of this motif in order to reawaken our very human anxieties. These two examples—there are numerous other ones—illustrate a trend in contemporary art, that of making use of the animal figure, the better to discuss the individual, society, and its ills.1 Animals are not used for themselves or in order to offer any sort of proecology discourse. They are there, once again, in order to help man raise himself up in opposition to the other; they are a form of alterity necessary to his own social construction. In this context, which is “conducive to transhumances of images and meanings,”2 animals force their way into the aesthetic realm and are helpful, among other things, in proposing a new form of social writing; they thus become, according to Catherine Grenier, “simulacr[a].”3

Freeze, or the Strata of Today

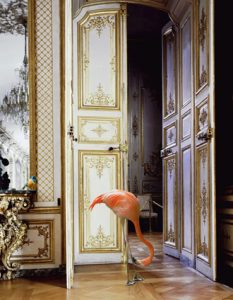

1. Karen Knorr, “The Battle Gallery (Chateau de Chantilly),” Fables, 2003-2008.

Just like the placing of flora and fauna under glass, neither is the stuffing of animals something of recent origin. It supplants embalming, which endeavored above all to preserve the essence of things without necessarily yielding a realistic image, and the craze for it seems to go hand in hand with the grand period of industrialization. However, the work of Karen Knorr (ill. 1) as well as that of the very young London artist Polly Morgan go to show that taxidermy’s move into the world of art has today been validated.

Already, in mid-nineteenth century, the Crystal Palace was the theater for playlets playing upon British customs and colonial activities wherein the actors were none other than stuffed animals. These “‘comic scenes’ are the humorous illustration of a fashion that will be echoed again at each new step toward an ever more radical modernization of techniques and technologies and will allow one to quell a generation’s fears of losing its foothold on reality and of drifting away from the natural order of things, which is shown.”4 The fall of this order, initiated by industrialization itself, made people aware at the same time of nature’s importance, thus instigating both a nostalgia for nature and the glorification thereof. From curiosity to a passion for technical advances and mechanization, in the twentieth century the world passed on to the terrors of the apparently uncontrollable postindustrial era. The human scale of the production line was shattered and consumer society, which had put people in such a joyous mood just a few decades ago, has become the symbol of refuse, detritus of all sorts, wastage, and the irremediable pollution of nature, leading toward its future demise.

Returning to the contemporary period, it is to be noted that the modern “cabinet” more often exhibits the curious than the marvelous. Fables are now obsolete and the world has become disenchanted. Even while preserving the desire for narration and the playful as well as intellectual quality of this site, the new cabinet is intended as the image of a dark and decadent nature. Even though, at first glance, the illusion of nineteenth-century positivism continues to have its effect, and even though the vintage furniture, antique jars, and other period objects are rearranged therein, faith in science and the hope of progress seem to have left the room. When the contemporary artist, against expectations, refills the cabinet with various items, this time it is done in order to denounce consumer society and to inculpate capitalist policies and uncaring governments, as is shown in the work Tate Thames Dig by the American Mark Dion. An archeologist of modernity, Dion creates a cabinet of curiosities from cast-off items dredged from the Thames between 1999 and 2000 and thus reveals to us, in living color, every stratum of our society.

A Postmodern Animal

This mashup of science—extending from taxidermy to cabinets of curiosities—with the aesthetic realm and quotations of the past leads us to think in terms of a kind of postmodernity of the animal figure. The art historian Steve Baker grazed up against this question in his work The Postmodern Animal5, published in 2000. An art of fragmentation is thus said to be the current taste, and the animal figure, too, is sliced to order. Baker labels “botched taxidermy”6» this way of showing a beast that is no longer intact but, rather, exhibited in tiny pieces, often as a hybrid of some sort or resewn together.

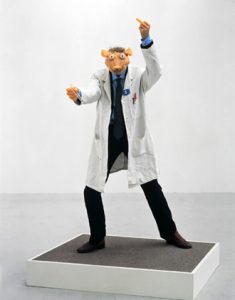

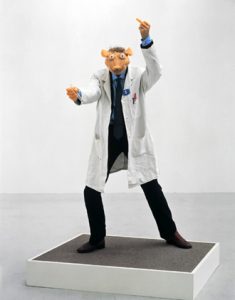

2. Isaacs, Say It Isn’t So, 1994.

Creating and showing an animal in pieces is, however, in no way an action meant to alert us as to the dangers of genetic engineering or to remind us of the violence done to animals. Once again, botched taxidermy, which is not always to be taken literally but rather as a form of imperfection or a kind of lapse, serves to render the animal figure less visible, “abrasively visible,” and thus forces us to go beyond just engaging in a reflection on the species. “Botching” can designate various forms of animal use, extending from the use of toy stuffed animals to their hybridization with other species and passing by way of the scragginess of bodily disintegration. Humor is often an integral part of the process, as is shown in John Isaacs’ 1994 work Say It Isn’t So (ill. 2).

This sculpture of a man dressed in a lab coat with a rat’s head may first cause some confusion and make one think that the point is to denounce the omnipotence of man. And yet, when one takes a closer look, one glimpses that the rodent face is in fact formed from a wax mold of a frozen chicken, to which have been added ears, hair, and eyes that give it a look inspired by comic-book art. This hybrid character carries in one hand a test tube and, with the other, it is giving the middle finger. A joke reminiscent of the canvases of Giuseppe Arcimboldo or simply an insolent gesture on the part of the artist, Say It Isn’t So is there more to disturb us, to upend our bearings, than to ask the question of what will become of nature.

Still Life: The Mirror of Modern Man

3. Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Dirty White Trash (with gulls) 1998.

These beasts, but also the castoffs of nature or industrial waste gathered and thrown together in order to give shape to man, a decadent man, seem to be the exclusive work of the artists Tim Noble and Sue Webster, and this for now going on two decades. The art of hybridization takes on its full scope here in trash-can sculptures made up, in the main, of animals that have been stuffed. Placed alongside the detritus of everyday life today, they go to form garbage heaps that are fully revealed for what they are only once they are lit up. What the shadow projected onto the wall then reveals are human silhouettes, those of the artists, in sometimes provocative, sometimes plaintive poses. These shadow sculptures, as the artists like to call them, harbor vermin and other kinds of animals that take over the urban zones within which the shadow of man ends up being hidden. As its title indicates, Dirty White Trash (with Gulls) (1998; ill. 3) shows us two stuffed gulls fighting over the spoils of trash cans. Once lit, the work allows us to discover the shadow of the artists seated back to back, one drinking from a stemmed glass, the other smoking a cigarette. While what the projected image offers is a moment of relaxation, the sculpture of cast-off items swipes its material (to be brief) from popular culture, extending here from junk-food consumption to the birds—here, gulls—that now thrive in cities, thanks to the presence of refuse.

Even though Noble and Webster never have issued any sort of clear-cut political opinion of their own, their life choices, as well as the materials they use for their creative works, say a great deal about how they position themselves within contemporary society. Deeply anchored within British popular culture, they show, with a measure of tenderness, both its excesses and its abuses. Like archeologists of the present, they step out into zones devastated by deindustrialization, accounting for the byproducts of unemployment and idleness while showing us the harm consumer society does as much to people’s bodies as to the environment. Nevertheless, these artists, as full members of this society, never criticize it totally. Just as light gives life to the jumble of dead animals and refuse, their own embeddedness within a British tradition—as may be seen in their titles (British Wildlife, British Rubbish) or in their cultural activity (birdwatching)—injects a sufficient whiff of nostalgia to transform this cabinet of horrors into a delicate work of protest art.

Notes1 While the works of Damien Hirst have been able to arouse a certain amount of scandal, they have not, for all that, been censored. Looking at this work dispassionately, it may be noted that, without taking into account the audience’s sensibilities and the taboo death represents in Western societies, the artist shows the organic reality intrinsic to the life of each human or animal individual. In the face of death—here, animal death, whether that death be natural or due to slaughtering—man succeeds only with difficulty in thinking reasonably about the (sad?) ordinariness of such events. “What this emotion-laden, overinvolved reading reveals is an inability to reflect serenely on the horror that surrounds us,” notes Barbara Denis-Morel in “L’animal à l’épreuve de l’art contemporain: le corps comme matériau,” Sociétés & Représentations, 27 (2009): 157.

2 Marianne Celka, “L’homme de la condition postmoderne dans son rapport à l’animal,” Sociétés, 4 (2009): 82.

3 Catherine Grenier, “Faire la bête,” in La revanche des émotions: Essai sur l’art contemporain (Paris: Seuil, 2008), pp. 167-83. The author makes the point that the animal figure is an effective simulacrum, for it is set within the same field of existence as man. Thus is it easy, via a process of identification, to slip from man towards the animal. “The simulacrum is an image that is effective only if one adheres to it. It is not a rhetorical figure, like metaphor, nor a mimetic image. The object that substitutes for a simulacrum is all the more an operational factor in identification as it is set within the same level of reality as that of the model to which it relates” (ibid., p. 168).

4 See, on this topic, Céleste Olalquiaga’s book Royaume de l’artifice: l’émergence du kitsch au XIXe siècle (Lyon: Fage, 2008), p.41.

5 Steve Baker, The Postmodern Animal (London: Reaktion Books, 2000).

6 Steve Baker, “One of the alternative French verbs for to botch, or to bungle, is cochonner,” ibid., p.64. [Translator: in French, un cochon is a pig, so cochonner literally means: to make like a pig, to make a mess.]

Steve BAKER, The Postmodern Animal, Londres, Reaktion Book, 2000.

Christian DEBIZE, « Cabinet de curiosités d’hier et d’aujourd’hui », dans Merveilleux ! d’après nature, cat. exp. , Château de Malbrouck à Manderen, Paris, Fage, 2007.

Catherine GRENIER, « Faire la bête », La revanche des émotions : Essai sur l’art contemporain, Paris, Seuil, 2008, pp.167-183.

La part de l’autre, cat. exp., Arles, Actes Sud/Carré d’Art, 2002.

Le cabinet des merveilles : Éternuements de corneilles, pied d’huître et œufs de léopard, cat. exp. Milan, Silvana Editoriale, 2008.

Merveilleux ! D’après nature, cat. exp., Paris, Fage, 2007.

Mythology, cat.exp.,Londres, Haunch of Venison, 2009.

Céleste OLALQUIAGA, Royaume de l’artifice : l’émergence du kitsch au XIXème siècle, Lyon, Fage, 2008.

Rachel POLIQUIN, The Breathless Zoo : Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing, Pennsylvanie, Penn State UniversityPress, 2012.