When contemporary artists use the sausage as a visual, a comical effect is to be expected. For Morgan Labar, who wrote his PhD on silliness and stupidity, this foodstuff, popularized through industrialization, deserves to be recontextualized within its long history. In earlier art and literature ribald and scatological references abounded but it is in contemporary works that the ludicrousness of having an animal-less flesh has been magnified.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Morgan Labar Sausage

SAUCISSE, s. f. (Cuisine.) ce mot dans sa propre signification veut dire une sorte de mets que l’on fait avec du sang & de la chair de porc assaisonnée ; c’est une espèce de boudin.

(…) Les saucisses de Bologne sont les plus estimées, & on en fait une consommation considérable en Italie, surtout à Bologne & à Venise, d’où on en porte dans beaucoup d’autres endroits. (…) le commerce de cette sorte de marchandises est plus grand qu’on ne s’imagine.

Diderot & d’Alembert, Encyclopedia…

The motif of the sausage almost automatically conveys a comical or absurd tone, without necessarily referring to its phallic connotations [1]. Is it its relationships to the digestive body – the lower corporal, as Mikhaïl Bakhtine might have said – and the symbolic equation drawn between ingestion, digestion and excretion that makes the sausage funny, even silly, sometimes even prone to the nonsensical? Could it, otherwise, be the fact that it is popular? This question of the “popular” gains sharp acuteness in the contemporary period, a moment where the seriality of the sausage – its industrial and mechanized production – turned it into a common and affordable meal, where it used to be, in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, a sophisticated delicacy. In its indifferent and repeated production, seriality brings an element which adds to the impression of silliness invoked by the sausage: the absurdity of the industrial reification of the living. To become thing (sausage) the animal must not only be slaughtered but transformed very quickly: undone in its shape to give it another, baser, one. Unity (of the living animal, unique and singular) is therefore impoverished and reduced to a standardized and cursory shape, produced in multiples (one might underline the similarity of this language with the one used in contemporary art). This text would like to assess the equation of thing + silly = silly thing through the use of the sausage in art history.

Funny sausages: satire and phallus

Chief symbol of fatty food, the sausage is the anti-Lent. In the 17th century, during Lent, German protestants would put out banquets of sausages and cold meats in front of catholic churches to mock their hypocrisy. Already, in the 15th century, Carnival was represented with a rosary of sausages around its neck (fig. 1: http://archiviostorico.teatrolafenice.it/scheda_d.php?ID=15712#lg=1&slide=4), and in the German Fastnachtsspiele, the priests fuck around with and eat sausages. In Rabelais’ The Fourth book, the Chitterlings of Wild Island are at war with Shrovetide, the embodiment of the austerity of those who fast.

This episode brings us back to the topos of all topos, the analogy between the sausage and the phallus. The queen of the Chitterlings is called Niphleseth, a word that Rabelais borrowed from the Hebrew where it stands for the male member. The analogy is even more explicit, bordering on the ribald, in another episode of comical literature. In Tristam Shandy, Sterne describes how Tom, after having inquired for some time as to how sausages are made of a female shopkeeper, dared to be more forward. The latter then “made a feint however of defending herself, by snatching up a sausage —- Tom instantly laid hold of another —- But seeing Tom’s had more gristle in it —- She signed the capitulation —- and Tom sealed it ; and there was an end of the matter” [2] .

Toying with the formal analogy between the sausage and the erect sex, Sterne underlines one of the obvious comical characteristic of the sausage: it is a penis and not a phallus, a male member unable to penetrate through lack of rigidity – not enough gristle in it – not “nervous enough”. It is therefore both a symbol of virility and of the incapacity to fulfill the latter, a figure of ridicule, of fiasco – even infamy – in a universe that is clearly phallocentric.

Ingestion, digestion, excretion

Bertrand Tillier underlined that the caricature of Louis-Philippe as a pear is both justified and “quasi inept” [3]. Inept and inert, the pear is reduced, below the animal, in a process of regression specific to stupidity that Deleuze qualifies as a “universal digestive and leguminous bottom”, before specifying that the tyrant has “not only the head of a bull, but that of a pear, a cabbage or a potato” [4]. One might add of a sausage, which compounds to the “digestive and leguminous bottom” the equivalence of ingestion/digestion/excretion: in a sausage one eats the digestive organ itself, through thing made from minced meat – shapeless – and stuffed in a gut.

The artist as charcutier

In Claes Oldenburg’s sculptures dating from the 60’s (fig. 2; http://www.sothebys.com/fr/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.81.html/2017/contemporary-curated-n09622), the sausages are openly scatological, just like in one of his first assemblages, precisely called Sausages (1957). Oldenburg imaged himself as a sausage-maker, while assuming the excrement-like character of his first works (he himself wrote : “The Store is cloaca”), going as far as considering that the art spreading though society at the time was a remedy to the constipation of the 50’s [5].

Started at the same time, Dieter Roth’s Literaturwürste (fig. 3; https://www.moma.org/collection/works/141853) are also artisanal homemade sausages, not industrial. The minced meat is substituted by minced books, although the recipe remains unchanged bar that one element: gelatin, fat and spices are mixed in with the books and the whole is then stuffed in an animal gut. The literary homage is paradoxical to the least, as the preservation of the original work in this weakened form concerns only its materiality, and not its significance.

The dawn of the industrial sausage: shapeless and seriality

Subsequent uses of the sausage in artistic practices seem to have left aside these traditions of satire or irony, of cloaca or of the phallic. In 1974, when Paul McCarthy performed Hot Dog, he jammed his throat with whole raw sausages and surrounded his head with gauze to block the food inside. The traditional themes that were sexuality, violence and disgust were therefore renewed by their association with the industrial output of foodstuff and consumerism. From that moment on, the vast majority of works using sausages and cold meats lost their comical sexual subtext to evolve towards the ridicule, the absurd, or silliness. For example, in the Wurst-Serie by Peter Fischli and David Weiss, dated 1979, a series of photographs narrated episodes of a story where the protagonists were sausages and cooking implements, one needs to recontextualize it in the context of the young punk scene in Switzerland.

Dumbed down sausage

Fig.4: Anonymous, Hans Worst, 1570 – 1650, engraving, 40 cm × 26,5 cm, Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam

Damien Hirst’s 11 sausages, of 1993, consists of a bastardized version of the works which brought him fame from 1991 onwards (the sharks, cows or sheep preserved in display cases with formaldehyde solution). Beyond the evident inspiration taken from Sigmar Polke’s Der Wurstesser (1963), it is to himself that Damien Hirst refers, by building a type of link between the dead animals of his previous works and their future as industrial food.

Wim Delvoye, proponent of one-upmanship within silly joke-artworks, created in 1999 the series Marble Floor, photographs of flooring, which, regardless of the title, are not made of marble but of cold meats, creating abstract ornamental patterns from slices of ham, salami and mortadella. The technical aspects of their production as well as their final aspect (cibachromes in saturated colors, large scale formats, limited editions) contrast greatly with the stupidity of the statement (a floor made of ham). In 2003, Delvoye pushed through with Embroidered Ham (Mr. Cloaca), a slice of (dry-cured) ham embroidered in blue thread with the effigy of Mr. Cloaca, the logo of Claoca 4, the fourth version of his excrement producing machine. The work itself is not the slice of embroidered ham but the large-scale photograph taken of it. The joke of embroidering ham is transformed, and the work becomes aesthetic, luxurious and non-perishable, therefore fulfilling all of the criteria necessary to make it digestible by the market.

Conclusion

Fig. 5: Peter Johansson, En korv är snyggare än din mamma / A mother, more beautiful than the sausage, 2019, video. Still from video by Bright Film; Chris Sanitate and John Rosenlund, clothes, mask and wig by Mikaela Artén and Folketeatret, Copenhagen. Produced for the exhibition National Therapy, Peter Johansson at the Swedish Institute in Paris, France 2019-20.

Charcuterie has become the epitome of the industrial food complex in the contemporary world, from the over consumption of cheap meat to our alienation with food itself. The loss of phallic, or even scatological, subtext, traditional levers in base humor, of which the Hanswurst character is the paragon (fig. 4), signaled a shift into absurdity and asemia, illustrated to an extent by the Literaturwürste : meaning, once minced up, mixed with lard and stuffed in a gut, is somewhat hard to find. Closer to us, Swedish artist Peter Johansson questions, through comical and disturbing works (figs. 5 and 6), the transformation of a vernacular product (the falukorv) into a cultural icon nearing nationalist folklore.

The sausage is even dumber when it is no longer a phallus but hails back to the shapeless, the indistinction of minced flesh, the process of digestion that compresses it and gives it its shape: it generates silence and inertia, brings thoughts to a halt.

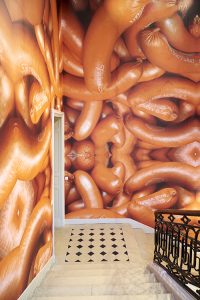

Fig. 6 Peter Johansson, Kärlekstunneln / The Tunnel of Love, 2014-2019. Staircase from the exhibition « National Therapy, Peter Johansson », The Swedish Institute, Paris 2019-20. Photo of the staircase by Laetita d’Aboville. Photos on the wall by Tord Lund and 3D work by Peter Johansson. Printer Lasse at Krelab.

It is almost as if the seriality of its production (at a time when contemporary art, in the 60’s, also starts producing serially) had transformed this signifier of signifiers into an a-signifier, a signifier of general indifference. Nevertheless, indifference is now the dominant characteristic of the sausage: to the mixture of flesh and the process of digestion, one must add the industrialization and seriality of its production. Shapeless, indifferent, amalgamating ingestion, digestion, excretion and sexuality in one movement – evoking cloacal indistinction in psychoanalytical theories as much as the definition of intercourse by the stoic Marcus Aurelius (“a friction of guts”) – when all is said and done, “alles ist Wurst”, “all is sausage”, but also and mostly “it’s all the same ».

[1], “Saucisse”, in D. Diderot et J. le Rond d’Alembert, Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, vol 14, p. 707. [2] L. Sterne, Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, 1760, vol. IX, chap. VII. [3] B. Tillier, “La caricature : une esthétique comique de l’altération entre imitation et déformation”, in Alain Vaillant (ed.), Esthétique du rire, Nanterre, Presses universitaires de Paris Ouest, 2012, p. 260. [4] G. Deleuze, Différence et répétition, Paris, Minuit, 1969, p. 196. [5] B. Rose, Claes Oldenburg, 1969, New York, MoMA, p. 32.

Morgan Labar is an art historian who specializes in contemporary art and artistic comedic practices. He currently holds a postdoctoral fellowship from the Terra Foundation for American Art at the INHA and teaches at the Ecole normale supérieure (Paris). His forthcoming book, In Praise of Dumbness. Regression and Shallowness in the Arts Since the Late 1980’s, will be published at the Presses du reel in 2021.