Anne Lafont offers us a foretaste of her key new research on the genre of massacres, which she examines in a perspective that encompasses the history of scientific expeditions, territorial conquests, and eighteenth-century colonization efforts. She blends American, European, and Caribbean images into the same corpus. Lafont admirably shows in what way representations of massacre scenes were, for those who commissioned such scenes, the moment that inaugurated a new political era.

Massacres: The First Atlantic Pictorial Genre?

Anne Lafont

“But these atrocious and cowardly men, eager to buy, through blood, forgiveness for the blood they have spilled, set no bounds at all on their excesses. Their motive is not pain, but fear; their barbarism is in no way impulse, but calculation; they do not at all commit massacres because they are suffering but because they tremble, and as their terrors are endless, there can be no end to their crimes.”

Benjamin Constant, Des réactions politiques in De la force du gouvernement actuel de la France et de la nécessité de s’y rallier (1796), chapter 1: “Des différents genres de réactions” (Paris: Flammarion, 1988), p. 61.

Scientific expeditions, territorial conquests, and colonization efforts are phenomena that stem from individuals’ and political communities’ desire for expansion. They are necessarily accompanied by acts of violence, for they happen through confrontation, struggle, and the snatching up of persons and goods. When it comes to the eighteenth century, one sees that the violence is twofold. For, grafted onto these ancient and recurrent phenomena are rebellions on the part of dominated populations—in contact with one another—that arise simultaneously on different points of the globe. Thus did the American colonists revolt against British tutelage beginning in 1770; the French Third Estate overthrew the Ancien Regime in 1789; and People of Color (whether slaves or free) took on the “aristocracy of the epidermis” on the island of French Santo Domingo as early as the Summer of 1791.1 Within the framework of a study devoted to the multiple ties that exist between the arts and societies, visual and artistic production relating to these three Atlantic territories in revolutionary turmoil can be considered as a dynamic whole. And furthermore, this whole can be linked to a connected history of art, in that that history reveals novel sites of contact and exchange (including violent ones) through images, objects, and their capacities for mobility.

Here the term mobility is not to be understood in the sense of “transfer” but rather in the less deterministic and less unilateral one of (real or conceptual) circulation of images and objects, whose fecundity may be observed at each point of anchor. In other words, what this boils down to is examining the transformation of pieces within the framework of their new appropriation as well as their effect on their successive environments.

Thus did it seem to me of interest to study the iconography of massacres in one time (the era of revolutions) and within one space (the Franco-American axis) that are rethought, since numerous images were indeed then springing up within this category, which may be defined as the ignominious murder of a large number of defenseless persons. The odious savagery of this specific type of crime stemmed from the number of persons being killed, from the immoral (nay, obscene) form of the killing, and at the same time from the asymmetry between the executioners’ arsenal and that of the victims. In the domain of art, this notion also implied the biblical episode of the Massacre of the Innocents, for which a plethora of imagery existed in the modern era.

A few factual features must be mentioned in order to understand these three revolutionary events in such a way as to facilitate a comparatist study of images (eyewitness testimony or cliches). And their overriding ideology, too, has to be reconstructed, whether it be independence-oriented, abolitionist, loyalist, monarchist, proslavery, or colonialist.

Three Revolutions, One Iconic Symptom

The American Revolution began in 1770, when some of the colonists decided to emancipate themselves from British political tutelage, as they deemed illegitimate a certain number of decrees (those reinforcing taxation of the colonies). Several insurrectional events pitting the colonists against British military forces then occurred in large cities along the Atlantic seaboard (Boston, Philadelphia, Richmond) until 1783, when the thirteen American colonies, assisted secondarily by French troops, succeeded in forcing the British crown to surrender and to recognize the independence of the United States of America. In 1787, the former colonies endowed themselves with a Constitution, and, in 1789, George Washington was elected president. The first French revolutionary events unfolded that same year, with the meeting of the Estates General at the Jeu de Paume in Versailles in June and the storming of the Bastille in Paris on July 14. A series of unique events then gave a special rhythm to the French Revolution, which became synonymous with the last decade of the eighteenth century. Among these events was the end of the monarchy, which coincided with the assault on the Tuileries Palace and the King taking temporary refuge at the French National Assembly on August 10, 1792. Those events were followed by the bloody and terrible September Massacres, which were the highpoint of revolutionary violence and, for this reason, were propitious for a relatively rich iconography.2

As early as 1791, several historical overlaps can be spotted between the French Revolution in the home country and what at the time were called the slave insurrections in the French colony on Santo Domingo—in other words, the Haitian revolutionary process (1791-1804). A patch of this history is of interest for the c. 1800 visual imaginary and thus merits being related in a clear way: the fires set on the plantations located on the Northern Plain of the island and the massacre of a thousand Whites that followed after the Bois Caïman voodoo ceremony, to which the priest and leader of black rebels, Dutty Boukman, had summoned several hundred slaves on August 14, 1791. Boukman was soon killed (on account of his legendary invincibility, his killers went so far as to display his head in the town of Le Cap, as had been done with the head of the Marquis de Launay, in Paris, following the storming of the Bastille). Yet resolute bands of armed men kept up their terrorist activities in several places on the island and soon chose a new leader in the person of Toussaint Louverture. The second episode symptomatic of the French Santo Domingan Terror is the sacking of Le Cap, which prompted the expatriation of more than ten thousand colonists panicked by the surge in violence on the part of former slaves.3 Thus, this article will cast into one and the same corpus American, European, and Caribbean pieces.

Visualizations of Massacres

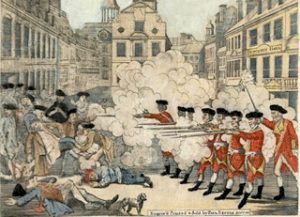

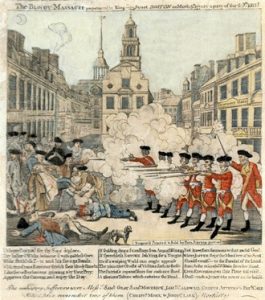

1. Paul Revere (1735-1818), The Bloody Massacre, 1770, engraving.

The Bloody Massacre (ill. 1) was executed by an American engraver of Huguenot origin, Paul Revere (1735-1818), a rebel and freemason whose print—an emblem for the American rebels4—clearly inspired the Spanish painter Goya when he did his picture about the extreme brutality of the Napoleonic Wars, Tres de Mayo (1814; Prado Museum, Madrid, ill. 2).5 This shows, moreover, the extent to which engravings were circulating in all directions between Europe and the American colonies; it also shows that the model did not systematically proceed from a colonizing center toward the peripheries at the confines of the Empire and, finally, that the Atlantic as a politico-artistic space very much did exist in the eighteenth century. Also, it is opportune to apprehend images from this perspective—at the very least, to have this alternative geography as a motivating factor—for, in denationalizing artistic productions, one can envisage their displacements as so many amendments of their meanings. The visual arts, more than any other kind of testimony, source, narrative, or representation—they may indeed pertain to each one of these categories—therefore require horizontal investigations into the permanency of ideas within the images and objects that give them material form, and such investigations are to be based on the existence of formal common denominators.

2. Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), Tres de Mayo 1808, 1814, oil on canvas, Madrid, Prado Museum.

Now, the goal of a massacre is to wear down the enemy group by a sudden and phenomenal killing of numerous individuals who make up this group without leaving the victims any alternative and with the assailants acting in a particularly fierce and relentless way. In Revere’s engraving, the bloodthirsty British soldiers behave like butchers—even though, more than a massacre, as the title suggests, it is a matter here of the execution of a small group of rebels.6 Written sources relate, moreover, an attack by stones coming from a few of the pioneers of the struggle for independence, and in particular the courage and involvement of the valiant Black, Crispus Attucks (1723-1770), who died in the fight. He is nevertheless the ghost in the image, for no African (even an archetypical one) can be made out among the rebels shown in this engraving.7

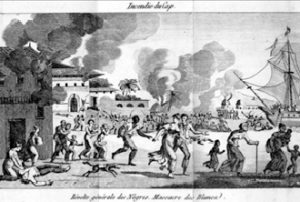

3. Incendie du Cap. Révolte générale des Nègres, Massacre des Blancs. Engraved frontpiece from the anonymous work Saint-Domingue ou Histoire de ses révolutions. Le récit effroyable des troubles, des divisions, des meurtres, des incendies, des dévastations et des massacres qui eurent lieu dans cette île, depuis 1789 jusqu’à la perte de la colonie. (Paris, 1800)., Une si jolie petite guerre, Saigon 1961-63, p. 261. © Denoël Graphic.

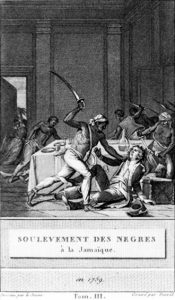

In the large engraving in the front of the volume devoted to the French colony, Saint-Domingue ou Histoire de ses révolutions (published in Paris in 1800),8 a procession can be made out in the foreground, with more turbulent incidents shown in the background (ill. 3). The image is therefore quite far removed from its cataclysmic title, Incendie au Cap. Révolte générale des Nègres. Massacres des Blancs (Fire at Le Cap/General revolt of the Negroes/Massacres of the Whites). This frontispiece, whose function is to offer a condensed version of the text that follows on the revolutions of French Santo Domingo, does not offer an illustration of the violence one might infer from the title, even if a young armed black man can be seen running after women, children, and old men who are white. The fire alone seems to threaten these people—including the Black at the center of the picture, who might also be part of the fleeing procession—though the lynching of a White by several Blacks in the background obviously recalls the racial confrontation of the overall scene. As for the representation of the massacre, we again are faced with a gap between title and image, in contrast to an—exactly contemporary—engraving whose euphemistic title “Soulèvement des Nègres à la Jamaïque en 1759” (Uprising of the Negroes in Jamaica in 1759) would not lead one to believe that the image fits perfectly into the iconography of carnage.9 In this case, the gap between word and illustration was reinforced, moreover, by the book’s Abolitionist bent.

4. Soulèvement des Nègres à la Jamaïque en 1759. Engraving by François-Anne David (1741-1824) after a drawing by Nicolas Lejeune (1750-18??), plate 5 following p.36, in L’Histoire d’Angleterre représentée par figures (Paris: Guyot et Milcent, 1784-1800), vol. 3 (1800).

By contradicting the text with which they cohabited in their respective book-objects, these two images from 1800 dealing with the question of the massacre of Whites in the Caribbean therefore functioned in a paradoxical manner. On the other hand, these engravings showed how keen—from afar, for these prints were designed in Paris—was the dread caused by the prospect of the bloody and pitiless revenge Blacks might exact upon the white colonists. Such dread was even fed at the time by a Creole Bonapartist current of opinion advocating the reestablishment of slavery in the colonies, where the “ferocious Africans . . . tigers, ever bloodthirsty and eager for carnage” belonging among the “savage, cruel, cannibalistic nations,” might pursue the massacre of the few Whites who had remained in place in order to secure the colonial wealth of metropolitan French families.10 This campaign legitimized the expedition of General Charles Leclerc (1801-1803), who was put in charge of the effort to retake control of the colony and reestablish slavery in all the colonies, from Guadalupe to Sainte Lucie (Saint Lucia) by way of French Guiana.11

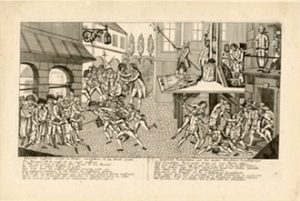

Things proceeded somewhat differently in France. But there, too, the phenomenon of massacres was tied to the act of revolution. It was even the supreme event thereof, the one whose horribleness, during the Summer of 1792, made it the tipping point between rebellion and terror. The September Massacres resulted in more than one thousand deaths in a few days’ time. Summary executions of persons suspected of counterrevolutionary plotting, or scheming and ploys preparatory to a foreign invasion, were then committed in the name of a necessarily expeditive and arbitrary form of emergency justice that authorized all sorts of excesses, including bloody settlings of scores. Pikes, knives, and the guillotine were employed full time in order to execute, in great numbers and without further ado, more or less suspect women and men. The engraving Horrible massacre (ill. 4) shows this quite well: a staggering number of crimes take place on just one improbable site, befitting the visual syntax, which efficiently represents the panic induced during the most lethal sequence in the French Revolution.

Capturing the Point of No Return

5. Johan Martin Will (1727-1806) Horrible massacre avant la Contre Révolution, 1792, engraving.

Thus, if the images are to be believed, revolutions happen through massacres—in other words, through the violent and brutal annihilation of the past via the killing of the men who embody it. They were imagined at the request either of the rebels (the American colonists frightening their compatriots by brandishing the image of the cruelty of British troops) or at that of conservatives (the French reactionaries or Creole colonists who, in images, were fanning the counterrevolution in order to forestall the advent of a more egalitarian era). Whichever clan commissioned the image, the massacre scene signaled, for those who commissioned it—whether they liked it or not—the impossibility of going backward and augured a new political era—a new one, without it necessarily being a better one.

6. Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, oil on canvas, Louvre Museum, Paris.

This crossing of a threshold opened by an acme of violence gives to the massacre scene in general some qualities that are particularly propitious for its visualization. This boomerang violence so well described by Benjamin Constant therefore enriched the visual arts in various forms, but, in its hesitant beginnings, it did not give rise to a pictorial genre in its own right because it remained too enmeshed in current events. On the other hand, these various engravings gave material form to a moment of iconographic and formal experimentation in the years before Romanticism, whose style manifestly lent itself more readily to the representation of massacres. Thus did the work of Eugène Delacroix, from The Massacre at Chios (1824, Louvre Museum) to The Death of Sardanapalus (1827, Louvre Museum, ill. 6), inaugurate the gradual displacement of these vile—and here public and Atlantic-area—crimes toward two areas of work that found nineteenth-century art: intimism and orientalism.

1 Florence Gauthier, L’aristocratie de l’épiderme. Le combat de la Société des Citoyens de Couleurs 1789-1791 (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2007).

2 As early as the eighteenth century, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing explained that painting—by which is meant the visual arts—had the capacity to condense several different times. He also noted that the work of art attained aesthetic heights when the artist chose the right moment—that is, right before the apogee of the action—and that it introduced a certain number of figures—episodes, as it were—charged with the task of embodying the past and future times of the instant to be shown. These considerations, as we shall see, are of particular interest for the iconography of massacres (see Lessing, Laocoön: An Essay upon the Limits of Painting and Poetry [1766], trans. Ellen Frothingham [Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1877], pp. 18 and 120 and elsewhere).

3 Carolyn E. Fick, The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990); see Part Two: “Revolts of 1791,” pp. 89-134.

4 In order to execute this image, which turned out to be iconic, Revere plagiarized a drawing by the Loyalist Henry Pelham (1748-1806), The Fruits of Arbitrary Power, or The Bloody Massacre. See Clarence S. Brigham, Paul Revere’s Engravings (New York: Atheneum, 1969), pp. 61-63.

5 Jan Bialostocki, “The Firing Squad, Paul Revere to Goya: Formation of a New Pictorial Theme in America, Russia, and Spain,” in Moshe Barasch, Lucy Freeman Sandler, eds, Patricia Egan, coordinating ed., Art: The Ape of Nature. Studies in Honor of H.W. Janson (New York: H. N. Abrams; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1981), p. 549-58.

6 In Pelham’s original version, there is no shop sign, whereas, in Revere’s, one can be distinguished—“Butcher Hall”—which was unquestionably chosen by the artist for its correspondence between the blood of the victims and that of a butcher’s stall.

7 The black contribution to the Boston revolt was reestablished in 1856—i.e., during the Abolitionist era—by the introduction of a central character, with African features, at the center of the chromolithograph done by John Bufford (1810-1870) after a work by William L. Champney (active 1850-1857).

8 The subtitle was as follows: Le récit effroyable des troubles, des divisions, des meurtres, des incendies, des dévastations et des massacres qui eurent lieu dans cette île, depuis 1789 jusqu’à la perte de la colonie (The horrifying narrative of the troubles, divisions, murders, fires, devastations, and massacres that took place on this island from 1789 until the loss of the colony).

9 Engraving by François-Anne David in L’Histoire d’Angleterre représentée par figures (Paris: Guyot et Milcent, 1784-1800), vol. 3 (1800), plate 5 following p. 36.

10 Quotations from two monographs by Louis Dubroca: La vie de Toussaint Louverture, chef des Noirs insurgés de Saint-Domingue (Paris, 1802), pp. 34 et 44, and La vie de J.J. Dessalines, chef des Noirs révoltés de Saint-Domingue (Paris, 1804), p. 14.

11 Yves Bénot and Marcel Dorigny, eds, Rétablissement de l’esclavage dans les colonies françaises. Aux origines d’Haïti (Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 2003).

ARMITAGE, David and Sanjay SUBRAHMANYAM. Eds. The Age of Revolutions in Global Context, c. 1760-1840. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

BÉNOT, Yves and Marcel DORIGNY. Eds. Rétablissement de l’esclavage dans les colonies françaises. Aux origines d’Haïti. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose, 2003.

BORDES, Philippe and Régis MICHEL. Eds. Aux armes et aux Arts! Les arts de la Révolution 1789-1799. Paris: Adam Biro, 1988.

FICK, Carolyn E. The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution from Below. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

GAUTHIER, Florence. L’aristocratie de l’épiderme. Le combat de la Société des Citoyens de Couleur, 1789-1791. Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2007.

GÓMEZ, Alejandro E. “Images de l’apocalypse des planteurs.” L’Ordinaire des Amériques [on line], 215 (2013). Posted February 22, 2013. URL: http://orda.revues.org/665

GRIGSBY, Darcy Grimaldo. Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

ROBERTS, Jennifer L. Transporting Visions: The Movement of Images in Early America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.