Following in the footsteps of Dada and Marcel Duchamp, a number of artists have linked art and life, to the extent that they sought to do without the object itself, which the workings of the art market had sacralised. Particularly active in the 1960’s, at a time when the status of the author was being called into question on all sides, these artists worked together to adopt critical and analytical positions that gave a place to those who collected, sold or staged works of art. Ghislain Mollet-Viéville is one of those who work to promote and sell this art, which contains a utopian, poetic and humorous dimension.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Thibault Boulvain

Ghislain Mollet-Viéville For a socialized art

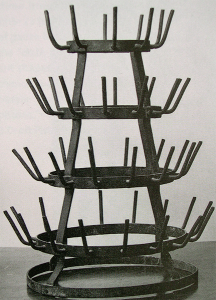

fig. 1: Marcel Duchamp, Porte-bouteilles, réplique, vers 1921, collection Hopi Lebel.

An alternative to the art of beautiful things

In the wake of Marcel Duchamp’s readymade, many artists have gradually turned away from the preoccupations associated with the traditional aesthetics of painting and sculpture, and relativised the artistic conventions imposed by the art market. Without being peremptory, they are putting forward alternatives by adopting an analytical and critical stance that increasingly takes into account the collector or curator, who is left in charge of presenting their work.

These artists are reassessing the status of their works by linking them to concepts and protocols, inviting ideas that relegate to the background the production of art objects on which it is not possible to intervene over time.

Lawrence Weiner

With his “Statements”, Lawrence Weiner places the collector at his own level, since it is he or she who controls the various displays of his works, with no limits imposed on their interpretation.

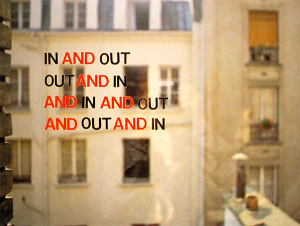

fig. 2: Lawrence Weiner : Statement n° 2037, 1971

In 1988, for example, I took charge of displaying the work IN AND OUT – OUT AND IN – AND IN AND OUT – AND OUT AND IN. Initially, I chose to display it on my window pane because, for me, it represented the ideal boundary between the inside (IN) and the outside (OUT) of my office.

I then displayed it in a completely different way, at a Picard Surgelés shop, during a joint gallery opening in 1988. Visitors would go into this supermarket – which was between two galleries – to see the work advertised in the exhibition programme. But when they didn’t notice anything, they came back out to see if there was anything in the window or on the front of the building. There was nothing there either. So they re-entered the shop to inspect it more thoroughly. But as nothing artistic truly stood out, the visitors came back out again. It was then that they were told that the work on display was in fact only existed in their comings and goings inside (IN) and outside (OUT) the shop. They had been looking in vain for the tangible product they usually get from the art market, whereas I was offering them a totally immaterial exhibition.

Within this mindset, many artists choose to involve us in their creations, giving us a voice to energise an art form that embraces the dimensions of life. It’s an art to be experienced rather than contemplated in an overly passive attitude.

fig. 3: boijeot.renauld.turon, place Stanislas à Nancy, 2014.

Art as social lubricant

Artists Laurent Boijeot, Sébastien Renauld and Nicolas Turon chose to work within this framework, and to put social cohesion at the heart of their participative works. When they were asked by the town of Nancy to question “how to consult the city’s residents in the most direct way possible, how to involve them as citizens”, their response was to set up and move around a 7-kilometre stretch very basic tables, chairs and beds for eight days. They had made them themselves and they were made available to everyone in the streets (including the mayor, who participated by sleeping there for two nights with Nancy residents, who were irresistibly drawn to this altruistic event).

This open-air habitat gave free rein to both the flow of ideas and to spontaneous dialogue, with the city as a common thread. It was a way for these artists to take a playful journey through the city, forcing people to open up to the humanity in each of us. The main aim was to re-enchant the city with art as a social lubricant.

fig. 4: Jean-Baptiste Farkas, IKHÉA©SERVICES, at the Grand Palais in 2009.

IKHÉA©SERVICES and the use of instructions

For his part, Jean-Baptiste Farkas, with his company IKHÉA©SERVICES, puts forward ‘services’ in the form of works that are not art objects but proposals, based on directives, protocols and instructions inviting us to act in a different way within society. The aim is to get us out of our comfort zone through unnerving experiences, and to come up with a set of unorthodox ideas.

Among other things, he suggests to contemporary art collectors that they remove from their collections all the works encased in beautiful moulded frames, all the photos and drawings surrounded by a pretty gilded mount, all the small sculptures arrogantly elevated by pedestals, glorifying them for no reason. In short, collectors are being asked to part with works revelling in embellishments that have nothing to do with the essence of art.

IKHÉA©SERVICES likes to create anomalies in our standardized lives. We’re therefore truly challenged to experiment with various situations, whose often unpredictable outcomes are always enriching. It can mean, for example, testing the risks we take in “lying at our own expense and at the expense of others” (another one of Jean-Baptiste Farkas’s protocols). Michèle Didier, following the instructions in 2016, lied outrageously by announcing that she had sold me her gallery. It was during the international contemporary art fair (FIAC) and it was a way of intriguing and making the art world react.

Following the buzz it generated, Jacques Salomon bought this ‘work’ and was given a contract certifying his ownership. Nothing else was given to him: only the proof of a scenario, that had already been experienced and could be re-enacted along with other lies, became part of his collection.

From there on, how should we view works that can be widely displayed in the art world, but that can also be used by all in their everyday lives? When artists and their interlocutors are united, with novel and reciprocal bounds, through a new art that develops within social relationships, what specific rules do works of art follow?

Experiencing the work of art as an activity

In such a paradigm the multiple activations of works over time, the legitimacy of the commissioner, the role of the author and of his signature, as well as the redistribution of roles, gave rise to the primacy of thoughts about experimentations and exchange, over the idea of the exclusive possession of an art object hung like a trophy on the wall.

The works of these artists correspond to the first definition of the term given by the dictionary: a work as an activity, a labour. “Being at work” does not necessarily mean producing a beautiful object. It may very well mean seeking to redefine works associated with processes that question their very characteristics. It can also lead us to question the data that makes us perceive ourselves as interpreters/authors, helping us confront art with our lifestyles. The aim for these works is for them to be renewed and experienced in a new light each time they are taken on.

fig. 5: Olivier Blanckart, Centre Pompidou, 1995.

Art, a major social phenomenon

The social contours of art, and the way it relates to fluctuating data, lead to the emergence of works that are inseparable from social reality, while at the same time questioning the conditions of their appropriation and exhibition.

In 1995, artist Olivier Blanckart’s Galerie des Urgences put up a huge banner on the façade of the Centre Pompidou: “Art against AIDS is useless: wear condoms!” This hard-hitting injunction was a reaction to the art world, which was content to simply organise events to raise money for AIDS charities.

Beyond its preventative focus, this action encouraged us to rally behind just causes. And, when brought to its natural extension, it showed us that, in art, we were witnessing the transition from an aesthetical art object to an ethical and social one.

This ethical turn comes from questioning the foundations of artistic practices, questions that were forged outside the rules dictated in an authoritarian way by the current art market.

A new economy is needed, one that takes into account art in relation to its societal context: it is not solely the work of art that counts, it is also what it will generate in each and every one of us.

Cognitive capitalism versus traditional capitalism

This statement should be explored on the basis of a cognitive capitalism, opposed to traditional capitalism. Traditional capitalism focuses on over-producing material goods to enable exponential financial speculation, with little concern for the well-being of workers. Cognitive capitalism, on the other hand, proposes that people should be enriched by thoughts and reflections that can be shared by involving everyone. In other words, unlike traditional capitalism, cognitive capitalism concerns an economy in which knowledge can be a property right, to be freely distributed.

Indeed, within our economic system, the material has not completely disappeared, but it is now dominated by the immaterial. This shift towards an economy that favours the creative faculties within each of us consequently leads to new relationships, based on a fair distribution of rights. It also results in the erasure of the ethical and cultural contradictions experienced within the community.

In the arts, creativity can no longer be based solely on material goods that are accumulated excessively, but rather on knowledge as intangible capital that increases in value as it becomes socialised.

Cognitive capitalism is thus moving us towards an economy of the immaterial, devoted to an art devoid of all materialist superfluities.

Given this state of affairs, the less we indulge in the private ownership of art, the more we will be able to share. What’s important is what happens between people, in other words, the interaction of the community with its mechanisms of transitions and encounters.

When an artist thinks up a work with a protocol, he doesn’t lose it by communicating it or giving it to others: on the contrary, he reinforces and enriches it from the moment it is passed on, commented on, and put into practice with getaways that become an art de vivre.

Bibliography

Collet, M. & Létourneau, A. É., Art. Performance, manœuvre, coefficients de visibilité, Dijon, les presses du réel, 2019.

Farkas, J.-B., Des modes d’emploi et des passages à l’acte – IKHÉA©SERVICES, Glitch, Riot éditions, 2020. Freely downloadable at : https://riot-editions.fr/ouvrage/dmd-dpal/

Gurita, A., & Ardenne, P., BDP, le catalogue, Paris, éditions Biennale de Paris, 2004.

Gurita, A., & Wright, S., XV, le catalogue, Paris, éditions Biennale de Paris, 2007.

Ickowicz, J., Le Droit après la dématérialisation de l’œuvre d’art, Dijon, les presses du réel, 2013.

Joint publication, « La disparition de l’œuvre », in nouvelle Revue d’esthétique, n°8, 2011.

Le Bon, L. ; Armleder, J. ; Copeland, M. ; Metzger, G. ; Perret,M.-T. & Phillpot, C., VIDES une rétrospective, Paris, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2009.

Lippard, L., Six Years: the dematerialization of the art object, New York, Praeger Publishers, 1973.

Mollet-Viéville, G., L’art minimal & conceptuel, Geneva, Edition d’Art Albert Skira, 1995.

Weiner, L., “Collection Public Freehold”, in Pratiques. Réflexions sur l’art, n°19, 2008.

Moulier-Boutang, Y., Le Capitalisme cognitif : la nouvelle grande transformation, Paris, éditions Amsterdam, 2007.

Ghislain Mollet-Viéville is an art agent, honorary expert for the court of Appeal in Paris, member of International Association of Art Critics, specialist of minimal and conceptual art, with a focus on its developments towards an immaterial, social art. He is a frequent speaker at the École Nationale d’Art : http://www.enda.fr/presentation/ and often writes for the Revue de Paris : http://www.revuedeparis.fr/l-art-non-artistique/