Take the floor! The floor is yours!”: in the second half of the 1970’s, Lea Lublin opened to all the possibility to speak freely about the nature of art. Hélène Gheysens recontextualizes this project – but also Lublin’s career – within a wider social, political and intellectual setting, one that compelled reinvention, up and to a new ethical way of creating art. The public space therefore the forum where an individual can assert himself within society.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac, Thibault Boulvain

Hélène Gheysens Psycho-Politics Of Public Space: The Investigations Of Lea Lublin (1929-1999)

In Interrogations et Entretiens sur l’art, Lea Lublin calls out to her audience: “Take the floor! The floor is yours!”. Lea Lublin’s call is conveyed in several works that, between 1974 and 1979, question the nature of art itself. This is one of the artist’s leitmotifs in order to think a non-authoritarian social articulation that affects both the intimate (the psychoanalytical dimension) and the collective (the political dimension) future of the individual. These questions are deployed in the public space, which is conceived as a physical space (to circulate in) and a mental space (to communicate in).

Public Space = Physical Space

Fig. 1 : Lea Lublin, Untitled (crowd), 1958, ink on paper, private collection (Buenos Aires). © Hélène Gheysens.

Lea Lublin’s consciousness of circulation spaces comes from the Surrealist heritage passed on to her by her teacher at the Buenos Aires School of Fine Arts, Antonio Berni. Lea Lublin shares his interest in representing the city. However, she adds to it a new way of thinking about communication. A drawing dated 1956 shows a tree in the process of merging with the edges of buildings, echoing the lines of antennas and electric wires, anticipating the artist’s interest in the fusion of the biological and the media. At a time when the brain’s electrical activity was being uncovered, the lamp in the corner seems to be a metaphor for human consciousness, necessarily dependent, partial and skewed. The question of awareness under influence is present in the many drawings that Lea Lublin dedicated to representing crowds between 1957 and 1958.

Ideological Pop

Lea Lublin continues her surrealist experiments in the spirit of the neo-dada artists, incorporating everyday objects into her work. For the Cara o Seca (Heads or Tails) exhibition, she created 3D “paintings-installations” that appropriated semiotic elements of urban space as well as household objects: not without humour, for example, a hairdryer becomes part of a gas mask.

Fig. 2 : Lea Lublin, Unknown Title, oil and applied objects on canvas, undated, (1965), black and white photograph, Lea Lublin archives (Paris). © Nicolas Lublin.

The artist presents chaotic compositions that echo shopping streets during rush-hour. Through these works, Lea Lublin alerts of the risk of personalities being destroyed by an aggressive capitalist environment. In the context of the development of behaviourist theories, she creates “warning-works” designed to awaken the viewers. We propose to call this practice, which uses pop media in a political and social perspective, “ideological pop”, following Luis Camnitzer’s theorisation of “ideological conceptual art”. By rejecting elitist art, this practice can be seen as part of pop art. It is art made by the people, for the people. Its inspiration comes from the street, the media or popular works (including vernacular ones), while its output makes extensive use of industrial materials, new media and found objects. However, unlike pop, particularly American pop, which celebrates consumer culture, this particular brand of pop, aware of the power of images to shape identity and social relations and fully ingrained within a Marxist tradition, claims the critical consciousness previously carried by Mexican muralists, Surrealists and the Cobra group. It asserts the revolutionary power of artworks.

Lea Lublin’s subsequent projects occupy the public space in a bid to raise people’s awareness. In 1969, the artist proposes Opération Commando Télécommandée de Communication (OCTC), as a script. Later, in a more direct attempt to fight the autocratic situation in Argentina, she seeks to transform collective action from “mass” art into “community” art through experiments such as Fluvio Subtunal and Flor de Ducha. These two works, both a path and a performance stage, use water as a key element of creation. Space, like water, lies at the boundary between the material and the immaterial.

Public Space = Mental And Discursive Space

During the Cold War, the intellectual public space constituted by culture was recognised as a place for debate and confrontation. Lea Lublin embraces this idea which was supported by the Cuban cultural revolution. Several articles published during her visit to Cuba in 1966 express her enthusiasm for the revolution underway. She does not see art as propaganda for a particular regime but as a true heir to the idea of the avant-garde, as a prophecy of a world to come. As such, the artist carries a social responsibility.

Fig. 3 : Anonymous, Nicolas Guillén and Lea Lublin in Buenos Aires, 1958, black and white photograph, Lea Lublin archives (Paris). © Nicolas Lublin.

This point of view is shared with two close friends, Nicolas Guillén and Rafael San Martin, who both played a role in this revolution. Nicolas Guillén, a Cuban poet, is an essential reference to understand the merging of culture and identity. Encouraged by his encounters with Federico García Lorca and Langston Hughes, his literary experiments buttress his social convictions, making him, for some, a negritude writer, or a precursor of the Black Arts Movement developed in the United States in the 1960’s. Although the precise circumstances of his meeting with Lea Lublin are unknown, its importance for both of them is undeniable. Their intense exchanges between 1955 and 1959, then still as close but more episodic until the 1980s, bear witness to this.

The second revolutionary figure close to Lea Lublin is Rafael San Martin, a fighter and writer whom she meets the same year that Ernesto Guevara landed in Cuba with Fidel Castro. Rafael San Martin’s parents were related to the Che’s, and he himself joined Fidel Castro’s column in the Sierra Maestra. He plays a key role in the spreading of the revolution. His international political obligations gradually distance him from Lea Lublin from the late 1970’s onwards. They do, however, share each other’s lives for brief moments of time, particularly in Paris. During these years, Lea Lublin pays particular attention to theories that place communication, and art, at the heart of interactions between the individual and society. At the same time, social sciences studying these relationships are developing: psychology, sociology, ethnology and anthropology. These disciplines take as a fundamental precept the porosity of identity and raise the question of how the individual mediates with his or her environment. Lea Lublin represents these various modes of mediation before experimenting with them. As early as the series Incitation au massacre, she references television. Later, she endorses the Arte de los Medios de Comunicación Masivos manifesto, written in 1966 by Eduardo Costa, Roberto Jacoby and Raúl Escari, according to which “the only thing that counts is the image of the artistic event reconstructed by the mass media”. Blanco sobre Blanco (White on White) illustrates this. This work depicts a couple engaged in sexual practice at the Pan-American Engineering Exhibition of 1970. Against a backdrop of heightened morality in Argentina, the eroticism of the depiction leads to the work being deemed subversive by the authorities and censored almost immediately, with the artist being taken to court for “obscenity”. Following her official conviction in Argentina, Lea Lublin presents a new work quoting Blanco sobre Blanco at the Comparaison salon in Paris. It is entitled Lecture d’une œuvre de Lea Lublin par un inspecteur de police (A Police Inspector Analysing A Work By Lea Lublin). The work features photographs and archival documents recounting this episode of censorship in the context of proto-dictatorial Argentina. It explores the different ways in which a work can be received in two distinct geographical spaces, and seeks to make the limits of free speech in Argentina perceptible to European viewers. Through this work, the artist puts forward a reflection on the role of the media in the face of power, showing that, paradoxically, a work supposedly meant to disappear can find lasting visibility in the press.

Fig. 4 : Lea Lublin, Reading of a work by Lea Lublin by a police detective, 1970, collage on canvas, private collection (Paris). © Nicolas Lublin.

The artist also turned her interviews into manifestos. In 1966, she publishes an article entitled “La peur de se libérer des béquilles mentales” (The Fear Of Freeing Oneself From Mental Crutches), in which she explains her research into movement and the multiplicity of points of view. Subsequently, she frequently accompanies her works with texts published in the press. This is particularly true of Culture – Dedans/Dehors le Musée (Culture Inside / Outside The Museum), a paradigm of her revolutionary and media-oriented thinking. Lea Lublin writes in the preface to this work: “We attempt to show all the mechanisms hidden by the capitalist system, through a new practice of Art, in order to bring about a total awareness that would open the way to a truly revolutionary culture”. As an extension of Culture Inside/Outside The Museum, Lea Lublin is attempting to bridge spaces of circulation with spaces of communication, in order to propose new modes of interaction. This is done under the influence of cybernetics, which combine individual and social psychology. By putting forth this novel vision, Lea Lublin becomes, in the words of Pierre Restany, a true “architect of information “.

The Artist As An Architect Of Information

Using cybernetics adapted to social sciences, the artist finds a way of involving spectators in line with her social concerns. With an aim towards collective emancipation, Lea Lublin sets up ‘systems’ in which the relationship between the individual and society is no longer one of domination. She creates environments that serve as new settings in which the individual can define his or her identity. By doing so, she follows in the footsteps of the latest discoveries in psychiatric theory, in particular behaviourism in considering that identities could shift or be provisional. Interrogations sur l’art, which emerged from Culture – Dedans / Dehors le musée, epitomizes her desire to articulate physical and mental space in her works of art. Lea Lublin develops them mainly in Europe between 1974 and 1979.

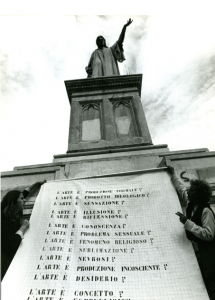

Interrogations is an artistic syntax being staged within an environment. A banner repeating an anaphora (L’art est-il ? Is Art?) can be hung indoors or outdoors. The latter is of particular interest to us. In Antwerp, the artist chooses to hang the banner on a lamppost, at eye level with passers-by, in order to question them. She also carries out a test on the Cathedral before hanging it on the emblematic statue of the painter Pierre-Paul Rubens on the Groenplaats, standing opposite the religious monument. Lea Lublin hung her Interrogations as a critique of the representation of the ideological and political power of Western art, long before statues were attacked (as was the case in Fort de France in 2020 with the statue of Joséphine de Beauharnais and Pierre Belain d’Esnambuc). She photographs her hand pointing to the two words on the banner: “ideologische” and “politische”. However, she does so in a way that avoids replacing one ideology with another, by putting forward an open and playful intervention. The photographs that have survived show a banner that dances in the wind around the statue, sometimes covering it completely but then quickly disappearing. The process is reused in Naples, initially on the statue of Jean-Baptiste Vico, a Neapolitan autodidact sometimes identified as a precursor of Hegel, and then on the statue of Dante, an emblematic author of Renaissance humanism. These critical interrogations of the universality of ‘icons’ of European intellectual culture, at the expense of other viewpoints, echo her sacralisation of a monument to Carlos Gardel, Argentinian tango legend and “true soul” of Latin America.

Fig. 5 : Lea Lublin, Interrogations on art, hung to a statue of Dante in Naples, 1977, black and white photograph, private collection (Paris). © Nicolas Lublin.

The Interrogations banner is part of a system designed to encourage audience participation. It invites people to express themselves. Lea Lublin records their responses, in order to give participants some feedback, but also to share within the installation these multiple opinions, by broadcasting video tapes, or “explanatory posters” bringing together photographs and transcriptions. Lea Lublin seeks to extricate herself from the determination of discourse by presenting a seemingly incoherent list of questions, the purpose of which is to prohibit any pre-established answers and thus to encourage personal statements and introspection.

The inability to answer these questions, which she herself characterised as a “trap”, can also be interpreted as an aporia, which could, in turn, be seen as one of the keys to the work, inviting us to restlessly question art and society, an essential condition of thought. Through this indeterminate shape, she sets the mind in motion.

Her desire for a parallel activation of physical and mental space continues later in her exhibition practice and her presence in the press. In 1993, Michel Field presented over several weeks, as part of the television show Cercle de Minuit, a series of cibachromes from Lea Lublin’s investigation of Marcel Duchamp’s footsteps in Buenos Aires. These pieces had previously been shown in two exhibitions curated by the artist in 1991. This continuation of exhibitions, via a relatively mainstream media program and in the context of a discursive definition of culture, demonstrates the artist’s ability to assert the importance of art in the psycho-political definition of public space.

Bibliography

Camnitzer, L., Conceptualism in Latin American art: Didactics of Liberation, 1st ed., Austin, University of Texas Press, coll.« Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long series in Latin American and Latino art and culture », 2007.

Gheysens H., « Paradoxes de la conscience orientée. Les parcours de Lea Lublin. » in « Mind Control, art et conditionnement psychologique XIXe-XXIe siècles », Histo.Art, n°11, Paris : Editions de la Sorbonne, 2019.

Jackson R., « Nicolas Guillén in the 1980s : A Guide to Recent Scolarship » in Latin American Research Review, 1988, Vol 23, N°1, 1988.

Lack J., (dir.), Why are we « artists »? 100 world art manifestos, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 2017.

Lublin L., « El Miedo a liberarse de los andadores mentales » in TESTIGO, Revista de Literatura y Arte, Enero, Febrero, Marzo 1966, Buenos Aires, Archivo Histórico de Revistas Argentinas (www.ahira.com.ar, accessed on the 5th of january 2020)

Rousseau P., Cosa Mentale, Art et télépathie au XXe siècle, exhibition held from the 28th of October 2015 to the 28th March 2016 at the Centre Pompidou Metz, Paris, Gallimard, 2015.

Turner F., Aux sources de l’utopie numérique, de la contre-culture à la cyberculture, Stewart Brand, un homme d’influence (2006), Caen, C&F éditions, 2012

Weber S. (dir.), Lea Lublin – Retrospective: [anlässlich der Ausstellung Lea Lublin – Retrospective, 25. Juni – 13. September, 2015, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, München], Köln, Snoeck, 2015

Hélène Gheysens holds a PhD in contemporary art history from Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her research lies at the crossroad of art, technology and the social sciences. Her thesis, entitled ‘Lea Lublin, architecte de l’information’, was supervised by Pascal Rousseau and defended in 2023. The same year, she organized the exhibition Lea Lublin, Arte será vida at the Galerie Michel Journiac in Paris and co-edited the book Amis, 120 ans avec le Musée national d’art moderne, published by the Centre Pompidou. Previously, she was co-curator at the the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art of the exhibition AntipsychiARTrie, relations entre art et antipsychiatrie depuis 1960. She is the founder of the Mission Recherche des Amis du Centre Pompidou, a program dedicated to researchers wishing to work with the collections of the the Musée national d’art moderne – Centre Pompidou. She has contributed to various archival tools, journals and publications, such as the CNAP database, the Aware Women Artists website, the journals Arpress, Cahiers du Mnam, Histo.Art, as well as various exhibition catalogues. She is also president of Fun Tech Adventures.