In studying the status of things over the long term, Amaru Lozano-Ocampo lay stress on the transition from the mysticism of the classical age to the secular world of modernity. According to him, the still lifes of the seventeenth century would be the ultimate testimony to a religious sensibility inherited from the Middle Ages. He insists, nevertheless, on the import of the readymades of Marcel Duchamp, who, in 1913, removed a thing from its strictly aesthetic or functional dimension in order to reintroduce into art the notion of invisibility. He reminds us that, for a certain number of artists, from Francisco de Zurbarán to Duchamp, everything, even a thing, becomes a subject that repopulates the universe.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

The Lost Language of Things. A History of the Still Life

Amaru Lozano-Ocampo

We have decided to treat the theme of the still life in a broad way, the better to grasp how the status of things has evolved within the history of art. This broad, historical take will allow us to reveal that the way in which things are represented is expressive of a change in sensibilities and, in particular, of a transition from the mysticism of the classical age to the secular world of modernity.

Representing Things in the Classical Age: An Initiation into the Language of the World

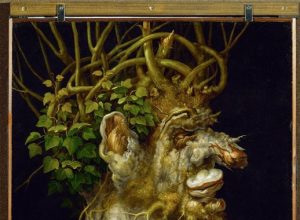

In how they relate to things, the works of the classical age express a still lively medieval sensibility. The still lifes of the seventeenth century are the last testimony to an already fading religious sensibility wherein all the elements remind one of the presence of a divine reality hidden behind what can be perceived. What the art of the representation of things has in common with the painting of the Middle Ages is the cryptographic character of its language.

Francisco de Zurbarán, San Hugo en el refectorio de los Cartujos (St. Hugh in the Refectory of the Carthusians), 1655, oil on canvas, 262 cm × 307 cm, Seville, Museo de Bellas Artes

To illustrate our argument, let us take Francisco de Zurbarán’s painting, St. Hugh in the Refectory of the Carthusians (1633). The artist establishes no hierarchy among the elements represented. Human beings, like the humblest things, are treated with the same degree of attention. The hands of the Carthusians and the round loaves of bread set before them offer a near-perfect chromatic unity. This similarity not only makes reference to the mystery of the Eucharist but creates a tie between men and things. Life is just as present in the bread as in the hand next to it; these pieces of bread are silent lives. The English and German expressions still life and Stillleben remind one of the deep-seated nature of these representations: a quite real but discreet presence, which is manifested not through words and is shown to he who knows how to see it.

The representation of objects on Zurbarán’s canvas echoes the Spanish mystical literature of the late sixteenth century. We can mention the famous phrase from Saint Theresa of Ávila, drawn from the Book of the Foundations “entre los pucheros anda el Señor” (“our Lord moves amidst the pots and pans”).[1] In the spirituality of the Middle Ages or the mysticism of the classical age (for, the mystic of the sixteenth century is an ordinary believer of the Middle Ages), one sees in each form the indications of a presence. God is everywhere and in each thing. The representation of things qua symbols of the omnipresence of the divine is in itself, for the seventeenth century, a medieval archaism. The bodegón of the Spanish Golden Age is the trace of a past sensibility in a world whose paradigm was undergoing a thoroughgoing change.

Sébastien Stoskopff, Still Life of Glasses in a Basket, 1644, oil on canvas, 52 × 63 cm, Strasbourg, Musée de l’Œuvre Notre Dame

Yet this sensitivity to things is expressed not only in Spain. Sébastien Stoskopff’s Still Life of Glasses in a Basket (1644) offers a lovely topic of study on this score. The glasses posed, one atop the others, in a basket are a memento mori, a classical reminder of the fragility of life on earth. This basket rests on a solid base that catches the eye of the beholder on account of a large fissure running through it. Stoskopff’s canvas presents us with a world stamped by the seal of fragility, wherein the hardest stones are broken. To support what we are saying, let us lean on some other canvases in which the same message is more explicit.

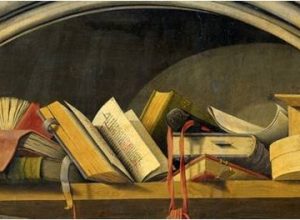

Carlo Crivelli, Virgin and Child, ca. 1480, tempera and gold on wood, 37.8 × 25.4 cm, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Two Virgins and Child by Carlo Crivelli support what we wish to establish. We are thinking of the Virgin and Child (1482), at Milan’s Brera Gallery, and the Virgin and Child (1480), now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In both cases, the Virgin is seated on a sumptuous throne in cracked marble. These cracked stones are portents of the Passion of Christ, who, seated upon the knees of his mother, apparently suspects nothing. These thrones have the same symbolic import as the melancholy gaze of the Virgin who is looking at some place beyond the picture’s frame. She sees that the stone is cracked and invites the viewer to notice it in turn. These Virgins and Child become premonitions of the Passion through the message things deliver to us.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Bodegón con limones naranjas, una rosa y un vaso de agua (Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose), 1633, oil on canvas, 62.2 × 109.5 cm, Pasadena, Norton Simon Museum

To paint reality in the nakedness of things is to reckon that such nakedness is a bearer of meaning. All the artifices of representations of the divine (angels, openings of the heavens) are superfluous. The entire universe is testimony to God’s grandeur, including a beggar or a bruised body. In the same way, the most discreet, the most fragile object can be an earthly sign of the divine. This is the profound meaning Zurbarán gives to things in a bodegón from 1633, now at the Pasadena Art Institute, which represents lemons, oranges, and a rose set near a glass of water. Before all else, let us recall that a good number of bodegones from the painting of the Spanish Golden Age were devotional objects. The objects represented in this picture constitute the words of a coded language. Purity and chastity are represented by the rose and the glass of water; as for the lemons and oranges, they are fruits associated with Easter and the Resurrection. Here we have an altar that represents the cycle of the Passion in the form of a mystical cipher (in the sense of code). The sliver plate on which the glass of water is set is, it too, integrated into this language, since it forms a silvery crescent characteristic of the representations of the Immaculate Conception. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s Immaculate Conception (1665), now at the Prado, and Diego Velázquez’s Immaculate Conception (1618), now at the National Gallery of London, both associate the Virgin with a silvery half moon, whereas the Father is associated with gilding and the disk of the Sun.[2] These are so many iconographic elements that allow one to understand the Marian symbolism of the glass of water set on a silver dish with a rose.

We have a similar case with A Cup of Water and a Rose, also by Zurbarán (1630, National Gallery of London). The peculiarity of this bodegón is its insistence on the association between the rose and the purity of the water. It is referencing, in the most explicit way, one of the names of the Virgin Mary: the Mystical Rose. As for the cup of water, it is making reference to the “Spiritual Vessel,” yet another name for the Virgin Mary. As it happens, these two words follow each other in the Litanies of Loreto which, while they were no longer known in the eighteenth century, were nonetheless an integral part of the medieval psyche. Zurbarán’s bodegón shows things so that the viewer will say their names. The things represented constitute the words of a sentence in the manner of a rebus or a piece of hieroglyphic writing. Thus, in describing what the viewer sees in the bodegón, he recites the litanies of the Virgin: Vas spirituale, Vas honorabile, Vase insigne devotionis, Rosa mystica (Spiritual Vessel, Honorable Vessel, Singular Vessel of Devotion, Mystical Rose). It is in the name of things that their meaning is to be found. Zurbarán’s picture is a silent book that communicates to us a message without words. Things are read therein like a text. Zurbarán’s bodegón says in a coded or elliptical manner what other pictures—like The Young Virgin (1632) at the Metropolitan Museum, where one again finds the glass of water and the roses alongside the Virgin in prayer—say more directly.

This method that appeals to several senses (sight, hearing) in order to construct the signification of a work will be found again in the avant-garde movements of the twentieth century and in particular in the work of Marcel Duchamp. The latter, following Zurbarán, was to develop a synaesthetic approach to his works.

The Lost Language

Nonetheless, it is also in the genre of still life that we can detect, as early as the eighteenth century, the loss of sign quality formerly attributed to things. Thus, little by little the still life comes to offer to the gaze of the men of modern Europe things presented as decorative objects. As early as the eighteenth century, the still life underwent two distinct and quite contradictory trends. The first one is tied to the emergence of the genre in Spain at the end of the sixteenth century and at the beginning of the seventeenth, which places the still life on an unbroken spiritual line with the Middle Ages; things are not represented solely for themselves but constitute a visual language. As for the second tendency, it establishes an aestheticizing relation to things and no longer makes them say anything. Through this form that is the still life, one seeks much more a mimetic pleasure than some sort of communication with a transcendent reality. Things become objects, bits of testimony to the virtuosity of an artist and to his capacity to recreate the world as he pleases. One notes there the influence of bourgeois commissions intended to decorate interiors outside any practice of private devotion. One’s relation to things is modified, as is testified to by academicism’s maxims about the still life, which it placed at the lowest rung in the hierarchy of pictorial genres. The secular relation to things goes hand in hand with the installation of a secular relation to the world.

Luis Meléndez, Un trozo de salmon, un limon y tres vasijas (Still Life with Salmon, Lemon and Three Vessels), 1772, oil on canvas, 41 × 62.2 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado

Luis Meléndez’s work offers an edifying example of the way in which the status of being a sign has little by little been confiscated from things. Although his still lifes are formally close to those of his illustrious predecessors Zurbarán and Sánchez Cotán, they were all painted between 1760 and 1774 for the Prince of Asturias’s Museum of Natural History. They constituted a survey of the fruits and vegetables produced in the Spain of the time. The function of these paintings is therefore encyclopedic, aesthetic, and in no way spiritual. If we transpose ourselves into the French field, we find again one and the same evolution toward aestheticization. When Diderot expressed enthusiasm for Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s The Olive Jar at the 1763 Salon, he wrote as follows:

Jean-Siméon Chardin, The Olive Jar, 1760, oil on canvas, 71 × 98 cm, Paris, Louvre Museum

That porcelain vase really is made of porcelain; those olives really are seen through the water they are floating in; you could simply take those biscuits and eat them; peel that fruit; and cut a piece of that pie.

This is the man who really understands the harmony of colors and reflections. O Chardin, it’s not white, red, or black pigments that you grind on your palette but rather the very substance of objects; it’s real air and light that you take onto the tip of your brush and transfer onto the canvas.

Diderot is praising the canvas for its mimetic qualities. This approach to the representation of things is the fundamental characteristic of the still life starting in the eighteenth century. The work’s value is tied to the perfection of its technical execution, but the thing represented no longer is meaningful in itself. Viewers taste the pleasure these colors and forms procure for their sight; two centuries later, Duchamp will call this retinal painting—which is, in fact, the triumph of decorative painting.

This is why the French expression nature morte [still life; literally, “dead nature”] is undoubtedly pertinent to our description of the representation of things as it was practiced from the late seventeenth century to the early twentieth century. Indeed, modernity lives within a natural world it considers dead. On the other hand, the use of this expression for bodegones and various Stillleben previously executed is erroneous, since, on the contrary, they show that the universe is the bearer of a soul. Thus, with the triumph of academicism and the gradual secularization of art, things lose their character as signs to become misunderstood hieroglyphs that have no other virtue than to render themselves useful or pleasing to our sight. Things have no life and have no other meaning than the one we give to them.

A Language Rediscovered

One of the intentions that is expressed anew in the twentieth century, and in particular in the creative work of Marcel Duchamp, is aimed at removing things from their strictly aesthetic or functional dimension. When, in 1913, Duchamp exhibited for the first time his readymade Bicycle Wheel, he created a scandal precisely because he refrained from any aesthetic or decorative imperative in his relation to things. Duchamp shows that things are signifiers in themselves and are not only the tools for our communication. They are elements of a language belonging to the world and not receptacles of the meaning we attribute to them. It is telling, moreover, that the first readymade was a moving object and therefore one endowed with its own dynamic, its own life. It is a thing that interacts with the world under the same heading as a subject and it is at the same time a highly humorous affront to functional operations, a wheel that can no longer turn and a stool upon which one can no longer be seated. Following the same logic, Duchamp creates a gap between the usual names of objects and the titles of the readymades. Thus, he never contested the various terms attributed to the urinal, whether it was the name Fountain given by Alfred Stieglitz, Buddha of the Bathroom, or Madonna of the Bathroom given by the Mercure de France in 1918. This discrepancy between the thing and its name is just as significant as the discrepancy that exists between the representation of a glass of water in the painting of Zurbarán and its designation as an offering to the Virgin Mary. In the same way, the shovel purchased at a hardware store in 1915, In Advance of the Broken Arm, or the ball of twine, With Hidden Noise, clearly specifies for us that things are more than what they allow to appear. They are bearers of a meaning that exceeds their function or the description of their form alone. Duchamp has recourse to a procedure of phonetic figurative representation close to the one used by Zurbarán. When he presented a window model called in English French window, which he detourned into Fresh Widow (1920), Duchamp was indicating that the window was to show rather than to be looked at. He invites the viewer to go beyond the appearance of the world and places things, through humor, on the level of the mind [esprit].

I considered painting as a means of expression, not an aim. . . . One means of expression instead of a complete aim for life . . . the same as I consider that color is only a means of expression in painting. It should not be the last aim of painting. In other words, painting should not be only retinal or visual; it should have to do with the gray matter of our understanding, not alone the purely visual.[3]

From the standpoint of modernity, Duchamp is a reactionary, whereas, from the standpoint of tradition, he is a revolutionary. His worldview does not pertain to modernity; he is reintroducing into art the notion of invisibility. In his interviews with Pierre Cabanne in 1966, he explains at length his sources of inspiration for The Large Glass and specifies the importance what he called the fourth dimension takes on in his work.

![Marcel Duchamp, La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (Le Grand Verre) (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass]), 1915-1923/1991-1992, replica executed by Ulf Linde, Henrik Samuelsson, and John Stenborg, under the supervision of Alexina Duchamp, oil, lead foil, lead wire, dust and varnish on glass panels, aluminum foil, wood, steel 321 × 204.3 × 111.7 cm, Stockholm, Moderna Museet](http://sciencespo.fr/artsetsocietes/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Duchamp-Stockholm-234x300.jpg)

Marcel Duchamp, La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (Le Grand Verre) (The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [The Large Glass]), 1915-1923/1991-1992, replica executed by Ulf Linde, Henrik Samuelsson, and John Stenborg, under the supervision of Alexina Duchamp, oil, lead foil, lead wire, dust and varnish on glass panels, aluminum foil, wood, steel 321 × 204.3 × 111.7 cm, Stockholm, Moderna Museet

Simply, I thought of the idea of a projection, of an invisible fourth dimension, something you couldn’t see with your eyes. Since I found that one could make a cast shadow from a three-dimensional thing, any object whatsoever—just as the projecting of the sun on the earth makes two dimensions—I thought that, by simple intellectual analogy, the fourth dimension could project an object of three dimensions, or, to put it another way, any three-dimensional object, which we see dispassionately, is a projection of something four-dimensional, something we’re not familiar with. It was a bit or a sophism, but still it was possible. “The Bride” in the “Large Glass” was based on this, as if it were the projection of a four-dimensional object.[4]

Zurbarán’s works, like those of Duchamp, offer us an objectless universe wherein everything, including things, are subjects. The object, ob jectum, being what is thrown before me, is an obstacle that presents itself, whereas the thing [chose], cosa, is a material or immaterial reality. The fundamental difference between these terms is that the object exists only in relation to me, whereas the thing exists by itself, independent of the fact that I exist or do not exist. The readymades destroy objects in order to repopulate the universe with things.

Interviewed by Philippe Collin, who asked him how one is to look at a readymade, Duchamp responded: “Ultimately, it should not be looked at. Through our eyes we get the notion that it exists.”[5] In giving a new status to things, what Duchamp is indicating to us is that existence is in things and not only in he who gazes at them. Without ever summoning up a theological vocabulary that would see in things the signs of the divine, Duchamp invites us to become aware of an existence outside of ourselves and, consequently, to establish an empathetic relation to the universe.

Notes

[1] The Book of Foundations of S. Theresa of Jesus of the Order of Our Lady of Carmel with the Visitation of Nunneries, the Rule and Constitutions, Written by Herself, trans. from the Spanish David Lewis, new and rev. ed. (London: Thomas Baker, 1913), p. 43.

[2] This cohabitation between silvery moon and golden sun is to be found again in a number of crucifixions, like those of Pesellino, now at Washington’s National Gallery, Raphael’s (1502), now at the National Gallery of London, and also Crivelli’s Crucifixion (1485), now at Milan’s Brera Gallery.

[3] From “A Conversation with Marcel Duchamp and James Johnson Sweeney,” an interview at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1955, NBC, in Wisdom: Conversations with the Elder Wise Men of Our Day, ed. and intro by James Nelson (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc., 1958), p. 97.

[4] Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), p. 40.

[5] “Marcel Duchamp Talking about Readymades” (interview by Phillipe Collin, 21 June 1967), in Museum Jean Tinguely, Basel, ed., Marcel Duchamp, exhibition catalogue (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2002) pp. 37-40.

Bibliographical Leads

DUCHAMP, Marcel and Pierre CABANNE. Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.

GÁLLEGO, Julián. Visión y símbolos en la pintura española del siglo de oro. Madrid: Cátedra, 1984.

GONZALEZ GARCIA, Juan Luis. Imagenes sagradas y predicacion visual en el siglo de oro. Madrid: Akal, 2009.

MÂLE, Émile. Religious Art in France: The Late Middle Ages: A Study of Medieval Iconography and its Sources. 1898. Ed. Harry Bober. Trans. Marthiel Mathews. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

_____. L’art religieux après le Concile de Trente. Étude sur l’iconographie de la fin du XVIe, et du XVIIe siècles en Italie, en France, en Espagne et en Flandre. Paris: Armand Colin, 1932.

SCHWARZ, Arturo. La Mariée mise à nu, Marcel Duchamp, même. Paris: Fall, 1974.

STEEFEL, Lawrence D., Jr. The Position of La Mariée mise à nu devant ses célibataires, même in the Stylistic and Iconographic Development of the Art of Marcel Duchamp. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Princeton University, 1960.

Amaru Lozano Ocampo holds a degree from Sciences Po Paris. He is working on a doctorate in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art at the University of Paris IV. His dissertation bears on the notion of darkness at the turn from the seventeenth to eighteenth century.