Amanda Herold-Marme, who is preparing a dissertation at Sciences Po on Spanish artists in Paris during the Francoist period returns to our seminar to examine the singular trajectory of Roberta González, an artist who worked in France beginning in the 1930s and until her death, in 1976. Herold-Marme spots in González’s work traces of war and of the political situation in Europe.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Amanda Herold-MarmeRoberta González: An Artistic Career Forget by War

Roberta González was a Franco-Spanish artist whose life and work were built upon her exposure to war. As a bearer of sufferings and opportunities, war was to mark her career, help lead her toward the discovery of her personal artistic path, and offer her the opportunity to make her own work and that of her father known on an international level. That will be our argument.

Born in 1909 of a largely absent French mother and the Catalan artist Julio González, Roberta González grew up around Montparnasse in her father’s family. According to family legend, she is said to have developed an artistic talent at a precocious age, as was noticed by Pablo Picasso himself, a close friend of her father.

ill. 1 Roberta González, Angoisse, 1936, oil on canvas, 81 x 57 cm, Fondation Hartung Bergman, Antibes.

At age eighteen, she took courses at the Colarossi Academy and frequented museums, but her early works were done on the basis of exposure to her father’s artistic work.

The curved lines that simplify the shapes of her rural scenes from the 1920s gave way, in the 1930s, to straight lines, which broke up volumes into facets, thereby multiplying the number of planes and viewing angles. González’s works moved away from observed reality and privileged an often nightmarish vision of things. The paintings executed in this Cubo-Surrealist style give off a sense of violence and distress, often conveyed, in Roberta’s work, by a female character, her head tipped back, with volumetric and angular forms rendered in a somber palette, as in Angoisse (ill. 1), executed in 1936.

A Work in Torment

This turning point coincides with the start of the Spanish Civil War. Geographically removed, the González family supported the Second Republic, as did most modern Spanish artists. Julio González’s most famous artistic show of support was his sculpture in iron entitled La Montserrat,1 which represented a courageous Catalan peasant woman. The violence of the forms and content of Roberta’s works during this period—a work in torment [une oeuvre en souffrance]—could be interpreted as a show of solidarity with the Spanish people, victims of war.

Quite rapidly, another war would come to touch the González family more directly, shattering the happiness of our artist and her new husband, the German artist Hans Hartung, an admirer of her father’s work. In 1939, they were obliged to leave the Paris region for the Lot in order to flee the Nazis who were hunting Hartung. The works done at the time by Roberta in a Cubo-Surrealist style were tinged with an ever more palpable sense of anxiety [angoisse]. Her introduction of veiled women, imploring the heavens with prayer, suggests a resurgence of faith as a way of facing increasing ordeals. Julio died suddenly in Paris in March 1942. In 1943, Hartung had to flee the Nazi invasion of unoccupied France, and his wife heard from him again only in late 1944, when he was hospitalized for an injury that led to the amputation of his right leg. The once-distant sufferings of war thenceforth deeply affected our artist. Indeed, Roberta wrote during this period: “It was said of this world that it was a purgatory; I believe that it is a hell, and often a large window open onto a view of paradise.”2 This duality of her worldview, which was cultivated by the ordeals of war, was to remain at the heart of her mature work, as we shall see below.

The Resumption of Artistic Struggle

Though the War was over, her return to the Paris area in the Summer of 1945 meant for Roberta a return to the “field of battle,” the “resu[mption of] the struggle,”3 a struggle that this time was of an artistic nature. Having lost her master, our artist sought to assert herself on the Parisian arts scene, which was divided by polemics involving figurative art vs abstract art as well as “geometrical” abstraction vs so-called lyrical abstraction, of which Hartung was one of the leading lights. With the opening of “a window onto a new pictorial universe,”4 his influence began to manifest itself on her work. Between 1947 and 1950, she created a portrait gallery of melancholic women whose faces remain in shadows dominated by somber hues. The sculptural immobility of the characters, who are drawn with rounded contours without any anecdotic details, contrasts with the latent energy of the superimposed rectilinear lines and with the strokes, which retain traces of the painter’s gestures.

Ill. 2 Roberta González, Jeune fille pensive, 1949, oil on canvas, 61 x 38 cm, Fondation Hartung Bergman, Antibes.

Like her “pensive girl[s]” (ill. 2), Roberta questioned her own personal artistic path in light of the countervailing influences surrounding her: “The problems abstraction poses haunt me, as do those posed by figuration.” She thus sought a “synthesis of the two forms of expression.”5 To this end, she introduced “all sorts of living elements, animals, plants, etc., and also objects” in order to be able “to juxtapose, to intermingle the figured form and geometrical forms.”6 The figures represent “mobility, plasticity, the form in movement ceaselessly transforming itself,” whereas the geometrical forms “express the permanence of immutable form.” It is “in contrasting them on the canvas [that] the instability/stability balance is created.”7 The vocabulary of her personal visual-arts language hovering between figuration and abstraction, which is based on the duality that remained at the heart of her work, was thus announced.

This coexistence of figured and abstracted motifs, scratched out or painted in the bands of paint vigorously spreading out over a less and less defined space, may be seen in Chant sombre (ill. 3), a large horizontal canvas from 1960. 8

The picture “came into being in one go. Dark, austere canvas, stripped down to the maximum extent possible.

Ill. 3 Roberta González, Chant Sombre, 1960, oil on canvas, 60 x 180 cm, Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM), Generalitat. Donation by Carmen Martínez and Vivianne Grimminger, Paris.

One of the best ones I’ve ever done. It’s the cry of a broken heart, of a soul that has lost all hope. Chant sombre (somber song), yes, but contained, muffled—the dark masses are beautiful.”9

An “Irregular” Artist

Ill. 4 Roberta González, Sens obligatoire n. 1, 1969, oil on canvas, 130 x 163 cm, Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM), Generalitat. Donation by C.* Martínez *and* V.* Grimminger, Paris.

Since the dark years of the War, black was the “master of [her] palette.”10 But having a “thirst for color,”11 our artist struggled to introduce gayer tones. This was perhaps facilitated by a fire she experienced at Bormes-les-Mimosa. According to Pierre Descargues, “the fire liberated her.”12 But above all, this liberation occurred at the moment when Roberta finally seemed to be at ease with and fully accepting of her personal artistic path. Her large-scale works at the time were characterized by dynamic strokes and composition, an explosion of color and an unprecedented expressiveness. In Portraits de Famille n. 2, 13 the shadows of the postwar world are lit up, breathing color and life into her personal reinterpretation of this family theme so dear to our artist. Sens obligatoire n°114 (ill. 4) from 1969 overflows with movement, color, and energy, like an expression of “cries of joy”15 sought for years. The suffering of the War had been mastered and assimilated into her personal style. Our artist was at peace with herself:

I am an “irregular” [un “franc-tireur”] … I cannot interest the figurative artists or abstract ones or the advocates of poor art (nor, moreover, rich art!) or the advocates of any other kind of art. Yet now, I am … indifferent as to whether I will be appreciated or not—I am following my path, and the rest pertains to God.16

While struggling to assert her own voice beyond the influence of her father and her first husband, and situated at the margins of the trends then in fashion, our Franco-Spanish artist also had to take a position in relation to the Franco dictatorship and to those opposed to it, the two camps using art in order to promote their respective causes.

Participation in the Pro-Republican Artistic Front

The Spanish political émigré community in France took advantage of the postwar anti-Franco climate in order to organize a pro-Republican artistic front designed to gather support for the Republican cause. These anti-Franco exhibitions were frequented by ministers, journalists, and personalities from the Parisian art world who bought a few works for the French State. Exhibitions of Paris-based Spanish artists also took place abroad.

In 1946, Roberta participated in two of these shows: the First Salon of Catalan Art, organized at the Reyman Gallery by the Friends of Catalans in Paris under the patronage of the French Office of Arts and Letters, as well as The Art of Republican Spain: Spanish Artists from the School of Paris, organized in Prague under the auspices of the Czech government.17 Among the works exhibited, which Jean Cassou described as “messengers from a country that … has suffered and fought,”18 there were five works by our artist in her anxious Cubo-Surrealist style. An artistic and political success, this arts event came slightly before the Czech government’s official recognition of the Spanish Republic’s government in exile.

Again in 1955, our artist participated in the exhibit “Homage of Spanish Artists to the Poet Antonio Machado” at the Maison de la Pensée Française in Paris. Like the poems of this famous Spanish poet, who died in exile in 1939, the exhibited works were intended to be the embodiment of “Spanish culture, which does not submit to servitude and tyrannies and longs for a free Spain, mistress of her own destiny.”19 Roberta’s engagement against the Franco regime seemed established.

Yet, in 1955 relations were normalized between Franco’s Spain, which was considered a lesser danger than Communism, and most of the Western democracies. In order to seal its acceptance on the international stage, the Franco regime increasingly made use of modern art. Grants and scholarships fostered the education and exhibition of a new generation of Spanish artists in Paris. A visit to our artist’s home in order to pay homage to her father seems to have been a rite of passage for some20.

The Cooptation of the Gonzálezes by the Apparatus of the Franco Regime

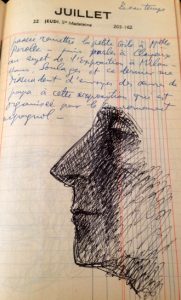

Ill. 5 Roberta González, 22 juillet 1954, unpublished notebooks, private Collection.

Young Spanish artists were not the only ones taking an interest in the Gonzálezes’ work. The Spanish arts apparatus also sought to coopt Spanish artists in exile. In July 1954, the Spanish ambassador to Paris asked Roberta to lend some of her father’s works in order to represent Spain at an official international exhibition. 21 Initially disposed to collaborate in the event, she was dissuaded, however, from doing so by Hartung, Pierre Soulages, and Clayeux. 22

On the other hand, Roberta ended up collaborating with Luis González Robles, a major player in the revival of modern Spanish art, in order to organize in Spain a series of exhibitions of the works of her father, her uncle, who was also an artist, and herself. Two shows devoted to Roberta and Julio González thus took place in Spain in 1960. In 1968 the first Spanish exhibition devoted to the entire González family, Los Tres González, was held. 23 In the catalog, the critic Carlos Arean claimed their artistic achievements for the glory of Spain: “all these exhibitions allow one to become more familiar, in Spain … with these three artists who are ours and who have been able to hoist so high the national flag on French soil.” 24

Roberta González’s life and work were built upon her exposure to strong influences: on the one hand, war, with its sufferings and its opportunities; on the other, the artistic model of her husband and, especially, that of her father. Starting in the postwar period, her work in torment opened out beyond these varying influences toward a personal artistic style borrowed from a duality between figuration and abstraction, stasis and movement, melancholy and joy. Furthermore, her way of positioning herself in relation to the politicization of Spanish art may seem contradictory. Exhibiting her “work in torment” at postwar pro-Republican arts events, she nonetheless ended up participating in shows organized by the apparatus of the Franco regime. Was this an instance of opportunism or of solidarity with the Spanish people, long left out of modern art? This complex question was posed, moreover, for numerous Spanish artists who were at the crossroads of various political agendas starting in the early postwar years and extending throughout the years of the Franco dictatorship.

Notes1 Julio González, La Montserrat, 1935, sculpture in iron, 163 x 59 x 42.5 cm, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

2 Letter from Roberta González to Marie-Thérèse González-Roux from Montauban, December 9, 1944 (Paris, Archives of the Kandinsky Library at the French National Museum of Modern Art; GON. R., item C06 8267).

3 Letter from Roberta González to Marie-Thérèse González-Roux from St. Porquier, June 8, 1945 (Paris, Archives the Kandinsky Library at French National Museum of Modern Art, GON. R., item C13 8274.

4 Catherine Valogne, Roberta González (Paris: Éditions Le Musée de Poche, 1971), p. 44.

5 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, January 22, 1951, private collection.

6 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, March 10, 1953, private collection.

7 Ibid.

8 Roberta González, Chant Sombre, 1960, oil on canvas, 60 x 180 cm, Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM), Generalitat. Donation by Carmen Martínez and Vivianne Grimminger, Paris.

9 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, February 11, 1960, private collection.

10 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, May 8, 1953, private collection.

11 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, February 11, 1960, private collection.

12 Pierre Descargues, Roberta González: Ombres et Profils, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Galerie de France, 1968), no pagination.

13 Roberta González, Portrait de famille n. 2, 1969, oil on canvas, 114 x 145.5 cm, Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM), Generalitat. Donation by Carmen Martínez and Vivianne Grimminger, Paris.

14 Roberta R. González, Sens obligatoire n. 1, 1969, oil on canvas, 130 x 163 cm, Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM), Generalitat. Donation by Carmen Martínez and Vivianne Grimminger, Paris.

15 Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, March 2, 1953, private collection.

16 Letter from Roberta González to Eusebio Sempere, June 15, 1970, Julio González Archives, IVAM Library, file 45, item 26_02 [the Author’s own translation of this passage into French has in turn been translated into English by the Translator].

17 The catalog reconstituting this exhibition, which was published in 1993, includes the translation into Spanish of the original exhibition catalog that came out in 1945 in Czech. See Artistas españoles de Paris: Praga 1946, catalog of the December 1993-January 1994 exhibition (Madrid: Caja de Madrid, Sala de Exposiciones Casa del Monte), p. 241-57 [the Author’s own translation of this passage into French has in turn been translated into English by the Translator].

18 Ibid., p. 249.

19 Hommage des artistes espagnols au poète Antonio Machado, exhibition catalog (Paris: Maison de la Pensée Française, February 4-24, 1955), p. 1.

20 Roberta mentions visits to her home by “young Spanish artists,” who often were accompanied by Father Roig, a professor at the School of Fine Arts of Valencia who was very active in promoting modern art in Spain, especially the work of Julio González. Apart from Eusebio Sempere, she does not mention the names of these artists, as in this excerpt from December 6, 1956: “The young Spanish students came by in the afternoon—quite charming and admiring, these young people. They expressed how much joy they felt spending such a good time here.”

21 This might have been the Milan Triennale.

22 Undoubtedly, this was Louis Clayeux, Director of the Maeght Gallery in Paris from 1948 to 1964. Roberta González, unpublished notebooks, July 22, 1954, private collection.

23 This show devoted to the works of Julio, Roberta, and Joan González (Julio’s brother, who died in 1908) took place at the Sala de Santa Catalina del Ateneo in Madrid and then at the Palau de la Virreina in Barcelona. It is to be noted that the first exhibition devoted to the González family took place in Paris, at the Galerie de France, in 1965, followed by a second show in 1971.

24 Carlos Arean, Joan González, Julio González, Roberta González, exhibition catalogue (Madrid: Sala de Santa Catalina del Ateneo, and Barcelona: Palacio de la Virreina, Barcelona, Cuadernos de arte, 1968), no pagination.

BibliographyArchival Documents

Roberta González’s correspondence with Eusebio Sempere and Marie-Thérèse González-Roux, 1960-1974. Archives Julio González. IVAM Library. Digitalized documentation. File 45. 30 items.

Roberta González’s correspondence with Marie-Thérèse González-Roux from St. Porquier, Toulouse, and Montauban, 1944-1945. Archives of the Kandinsky Library at the French National Museum of Modern Art in Paris. Call numbers C1-C13. 8262-8275. 23 items.

Roberta González’s unpublished notebooks, 1951-1976. Private collection.

Works

AREAN, Carlos. Joan González, Julio González, Roberta González. Exhibition catalog. Madrid: Sala de Santa Catalina del Ateneo, and Barcelona: Palacio de la Virreina, Barcelona, Cuadernos de arte, 1968. No pagination.

Artistas españoles de Paris: Praga 1946. Exhibition catalogue. Caja de Madrid: Sala de Exposiciones Casa del Monte, December 1993-January1994. Madrid. 306pp.

DESCARGUES, Pierre. Roberta González: Ombres et Profils. Exhibition catalogue. Paris: Galerie de France, 1968. No pagination.

Hommage des artistes espagnols au poète Antonio Machado. Exhibition catalog. February 4-24, 1955. Paris: Maison de la Pensée Française.

VALOGNE, Catherine. Roberta González. Paris: Éditions Le Musée de Poche, 1971.