Through Chim’s biography, Carole Naggar raises the question of war photojournalism, its methods and motivations. Deeply disturbed by war as early as his youth in Warsaw, Chim lived through all the major conflicts of his time, starting with the Spanish Civil War, wherein he acted as a committed observer who sought to affect viewers at the deepest level. Cofounder of the Magnum Photos agency after World War II, he would continue to embody the photographic heroism that originated in Spain, doing so until his death at the end of the Suez Crisis, as he shuttled back and forth between the two camps in search of the right images to depict unspeakable War.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Carole NaggarChim (1911-1956),

A peace Correspondent Who Died in War

From the Spanish Civil War to World War II and the Suez Crisis, Chim photographed wars. Yet he never was a war photographer and always sided with the weakest. He was especially interested in the effects conflicts had on civilian populations and on children, the first victims of any war.

Chim’s parents and his aunt wearing a yellow star. Otwock, Poland, 1940s.

Dawid Szymin’s early life in a family of Jewish intellectuals from Warsaw was peaceful. But soon his life was marked by war. Warsaw was shelled on August 1, 1914. His family moved to Minsk, in the Ukraine, where the political situation quickly became unstable, and, in 1916, they fled again to settle in Odessa. In 1918, when Poland achieved independence, they returned to Warsaw.

Dawid studied in Leipzig, at the Academy of Graphic Arts and Book Design, then at the Sorbonne, and, starting in 1932, he became a photojournalist and adopted the name “Chim.”

The work Chim did starting in 1934 for Regards, a left-wing weekly that launched photojournalism in the prewar years, coincided with a period of strikes, demonstrations, and political gatherings that were often violent. It was during his first two years at the magazine that Chim served his apprenticeship learned his trade as a photojournalist. The social struggles of at the time gave him the opportunity to become an attentive, activist chronicler. He sought not only to report the facts but also to construct in-depth stories and to prompt the reader to react passionately to these reports.

In June 1936, Chim became a special correspondent for Regards and went to Spain with Robert Capa and Gerda Taro. During the three years of war, Chim would shoot twenty-five reportage for that magazine. The Spanish Civil War sparked a campaign of international solidarity: more than 40,000 volunteers from around the world joined the International Brigades, risking their lives for the cause of the Spanish Republic.

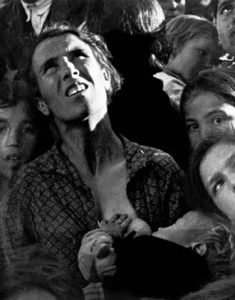

A woman listens to a speaker. Extremadura, Sapin, May 1936.

Chim traveled all over the Spanish territory. Among his most famous photographs of the conflict, one remembers those of the land occupations by the peasants of Extremadura and the field Mass in Euskadi, on the Basque front, as well as the portraits of the Asturian dinamiteros. He also photographed writers and artists such as Rafael Alberti, José Bergamín, Federico García Lorca, and Pablo Picasso, as well as major political figures such as Winston Churchill, General Adenauer, and Dolores Ibárruri, La Pasionaria. Unlike Capa and Taro, Chim rarely did photographs of combat, preferring a more reflective and descriptive method of working.

Yet in early 1939, Franco was victorious. In February, Chim found himself on the hilltop above Le Perthus, where endless lines of refugees, wrapped in blankets, turned in their weapons to French gendarmes. Nearly 500,000 people crossed the Pyrenees in this way, part of the greatest exodus of the century. For Chim as for them, the dream of a free Spain had come to an end. On May 23, he shipped off for Vera Cruz on the S.S. Sinaia along with 1,600 refugees, photographing life aboard the ship. This melancholy reportage, published in Life and the Illustrated London News among others, was his last on that war.

When World War II broke out, Chim, who was in Mexico at the time, decided to go to the United States in order to keep his family out of danger, and he settled in New York, where he joined a small photo lab, LECO. Later on, he worked as a photo interpreter at the Medmenham camp, near London, and helped in preparations for the Normandy Landing. In 1945, he learned that his parents and his entire family had died at the hands of the Nazis.

In 1947, Chim cofounded the Magnum Photos agency with Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and George Rodger. In the course of his reportage “We Went Back,” which he did for the magazine This Week about key places of the War and the Landing, Chim went to Germany. It was there that he made his best images. In the portrait he drew of German civilians crushed by the War, his absence of prejudice was remarkable. He underscored the courage of the population, which was trying to remake their lives: workers clearing away gravel amid the ruins of Berlin; women cultivating small vegetable gardens surrounded by the ruins of homes and stores; a child asleep in his baby carriage in front of the wrecked walls of Essen. In a magnificent photo taken in Berlin in front of the Brandenburg Gate crowned by its half-destroyed quadriga, a man accompanied by his young son has come to a halt. He is pulling a small wagon with a baby in it. Chim’s shadow is cast upon the ground before them.

At the Dachau concentration camp, his photographs of the brick ovens and of the Buchenwald trials proved, for once, to be devoid of all empathy. They offer a distanced, indeed icy, report. Chim did not neglect to photograph a sign full of black irony: “Here, cleanliness is a duty. Don’t forget to wash your hands.”

In the Spring of 1948, Chim received a commission from UNICEF to photograph the living conditions of Europe’s children. Thirteen million of them had been affected by the war. Himself an orphan, Chim projected his own feelings of mourning, loss, and abandonment onto these children who never had a childhood. That explains the bond of sympathy visible in these portraits, and this is undoubtedly one of the reasons why the photos possess such a piercing and tender quality.

A child playing amid the ruins of Vienna, 1948.

Homeless orphans, these children spent their first years in underground shelters, bombed-out streets, burned-out ghettos, refugee trains, or concentration camps. In order to survive, they had no other choices but theft, the black market, resale of cigarettes and the metal from shell casings, or prostitution. They are clearly survivors: Greek children who became refugees after the Greek Civil War; Hungarian adolescents in detention centers; in a Viennese refugee camp, a small girl clutching a crust of bread; in Rome, a child in an orphanage, blind and armless, who is lip-reading; a young girl from Naples, victim of a rape, with a haunted look; and, of course, the unforgettable Terezka: when her teacher asked her to draw her house, she could only produce a whirl of confused, frenetic lines.

But Chim also photographed a few scenes of hope: children at work in a print shop; boys in the “City of Children,” near Budapest, which was run entirely by young people; and a small Italian girl laughing, her face tilted toward her horse.

Over a period of more than three months, this reportage brought him to five countries: Austria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, and Poland. With a total of 257 rolls of film in his Rollei and his Leica, he went well beyond the simple assignment he had received in order to draw an in-depth portrait of children growing up amid the ruins of their parents’ world.

Following this reportage, Chim avoided the territory of Eastern Europe and, based in Italy, worked on social issues like illiteracy and religious festivals as well as on portraits of artists and Cinecittà actors.

In July 1956, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser declared the nationalization of the Suez Canal. On October 14, Nasser announced his intention to attack Israel and, on the 29th, Israel counterattacked with the help of Great Britain and France. Chim, who had not worked as a war correspondent since 1939, was in Greece at the time. Ignoring his colleagues’ advice, he decided to cover the conflict.

Allied victory was at hand when General Hugh Charles Stockwell, head of British armed forces, received a cease-fire order under pressure from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Port Said was in ruins, several thousands of wounded were crammed into hospitals, and the starving population was ransacking stores. Electrical lines had been cut and sewage water was pouring into the ruins. Chim, who was a passionate supporter of Israel, nevertheless chose to side with the Egyptian civilians. He teamed up with the Paris Match journalist Jean Roy, a knockabout journalist and risk taker. He photographed scenes of desolation: collapsed homes; families searching in the ruins for a few possessions; piles of bodies in the streets; a crowd attacking a flour depot, and so on. In the midst of the chaos, he remained perfectly calm and, according to several witnesses, took enormous risks and behaved as if he were invulnerable.

Chim in Paris in 1933.

On November 9, in the evening, an informant alerted Jean Roy about a prisoner exchange that was to take place at El-Kantara. The next day, Chim and Roy set off in a Jeep to cover the event. Traveling at high speed toward Egyptian lines, they did not stop when a warning shot was fired and were killed by several bursts of Egyptian machine-gun fire. Their Jeep zigzagged and then tipped over into the freshwater canal running alongside the trail. Chim and Roy thus died an absurd death, three days after the cease fire.

“I want to be at the heart of the action,” Chim had written in his last letter to Magnum. This desire for belonging came from a man who was perhaps weary of the distance he felt between the world and himself, weary of the subtlety, the ambiguity, the irony, and the wisdom for which he was known, but that in the end he had wanted to abandon in favor of a life of action.

Bibliography

BARBIELLINI AMIDEI, Rosanna, et al. La casa madre dei mutilati di guerra. Rome: Editalia, 1993.

CARTIER-BRESSON, Henri, Kosme DE BARNANO, Ramon ESPARZA, Josep Vicent MONZO, John G. MORRIS, Ben SHNEIDERMAN, Eileen SHNEIDERMAN, and David SEYMOUR CHIM. Exhibition catalog. Valencia: Institut Valencia d’Art Moderne (IVAM), 2003.

GIPS, Terry. Close Enough: Photography by David Seymour (Chim). Exhibition catalog. College Park, MD: College Park Art Gallery, University of Maryland, 1999.

NAGGAR, Carole. David Seymour: Chim. Paris: Photo Poche, 2011.

NAGGAR, Carole. David Seymour: Vies de Chim. Biarritz: Contrejour, 2014.

NORDSTÖM, Alison. Chim: Photographs by David Seymour (Selections from the George Eastman House). Catalogue. New York: International Center of Photography, 2007.

PHILLIPS, Christopher. David Seymour “Chim”: The Early Years, 1933-1939. Exhibition brochure. New York: International Center of Photography, 1986.

SEYMOUR, David, Inge BONDE and Nan RICHARDSON. Eds. Chim: The Photographs of David Seymour. Boston: Little Brown and New York: Umbrage Editions, 1996.

_____ and Tom BECK, David Seymour (Chim). London: Phaidon, 2005.

WARREN, Lynn. Ed. “David ‘Chim’ Seymour.” Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, Vol. 1. London: Routledge, 2005.

YOUNG, Cynthia. Ed. The Mexican Suitcase: The Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives of Capa, Chim and Taro. New York: International Center of Photography/Steidl, 2011.

_____. Ed. We Went Back: Photographs from Europe 1933–1956 by Chim.

New York: International Center of Photography, 2013.