Art historians have gone to work on Italy’s colonial past. Yet visual sources for such a history remain rather rare, either because they have been destroyed or because they have been covered over or willfully omitted.

Laura Iamurri opens a few possible paths of research and recalls that colonial exhibitions were indeed documented: the works were presented in the illustrated press and in public spaces, in major Fascist exhibitions, at the Venice Biennales of the 1930s as well as the Milan Triennale in 1936. Colonial stereotypes were tried out there: white conquering heros and black savage dances.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Laura IamurriSurrounding Ethiopia:

Images and Rhetoric Devices from a Colonial War

A History to Be Written

Italy’s colonial past remains a field to be explored. While one can already count a number of anthropological and historical studies, the same cannot be said for the domain of Art History. Known works are rather scarce, have been covered over or were destroyed after the War, and now are scattered among public and private collections where there is no interest in showing them. For lack of available works, art historiography finds itself at a dead end, and the topic continues to be ignored in Italy as well as at major international exhibitions, including during the latest event the Guggenheim Museum of New York City devoted to Futurism.1 In the lines that follow, I shall limit myself to pointing out a few possible directions for research on this topic as it exists in its still fragmentary state.

The visual celebration of Italy’s African adventure was set within the artistic policy of the Fascist regime, and it was, as a matter of fact, in Italy that colonial exhibitions became exhibitions of colonial art (Rome, 1931; Naples, 1934).2 Research on this topic nonetheless encounters some difficulties that are undoubtedly tied to the embarrassment felt regarding the history of Italy as a colonizing country and that are heightened by the closing of the Istituto Italiano per l’Africa e l’Oriente (ISIAO), of its archives, and of its library.3 Fortunately, a catalog exists of past paintings, sculptures, drawings, and engravings from the ISIAO’s Museo Africano collections. Black-and-white reproductions show a characteristic register of colonial exhibitions, and some of those artists, though often little known, presented their works in major Roman exhibitions and even, during the second half of the 1930s, at the Venice Biennale, amid an atmosphere of imperial celebration.

Fig. 1. Arturo Martini, An XIV. Le lion de Juda, 1936 (œuvre détruite)s.

While this corpus awaits an exhaustive study, the traces the Ethiopian War left on the work of Arturo Martini are, however, quite conspicuous. We know, under the title Hercules, of a fragment connected with a lost group that was exhibited at the Milan Triennale in 1936 as Year XIV: The Lion of Judah. We see in photographs (see fig. 1) that the interpretation of the victory of the Fascist army (Hercules) over the Ethiopians (the lion) was condensed into a sort of athletic allegory, a somewhat hypnotic dance scene in which the body of Hercules is shown less for its raw strength than for its geometrical harmony. The heraldic composition and the archaic language bring out a strategy used to distance oneself from the barbaric reality of colonial war.

The second sculpture is better known. The Tito Minniti, mentioned in 1930s catalogs under the title Heroes of Africa, makes reference to an episode in the war to which a young Italian airplane pilot had fallen victim. The Italian press reacted with indignation to this incident, and Martini expressed the emotion aroused by the news coverage in a monumental recumbent figure, his multiple mutilations covered over by a sheet and his head in a sort of cloth basket held up by his arm: the gesture of a martyr, evocative of the Crucifixion, and the celebration of the hero offer a wealth of classical reminders. Although Martini’s work as a whole has given rise to numerous studies, these sculptures devoted to the conquest of Ethiopia have not occasioned any particular reflections. The sculptor left us no commentaries thereon, and we are familiar only with his preoccupation concerning the economic consequences of this colonial war.4 It is, moreover, rather surprising to learn that the Tito Minniti was executed independently of any commission and at the artist’s own initiative—which is unusual for a bronze of such large dimensions.

Since the late 1920s, a site had been set aside in Rome for the celebration of the war and of its aftermath: the Casa Madre dei mutilati e invalidi di guerra. In the courtyard of the building’s annex, created in the 1930s, Giuseppe Antonio Santagata and Cipriano Efisio Oppo painted, in 1936-1938, some frescoes devoted to conflicts and battles won by Italy since World War I. Presently the seat of the Court of Appeals, the public is not granted admission to this annex today. In the early 1990s, a photography project was undertaken on the occasion of the publication of a book about the Casa Madre. A single image of the courtyard frescoes shows at the upper right, above a door, a frieze featuring a fight between an Ethiopian soldier and an askari: this project in effect avoided offering any images of the African wars, despite their recurrence.

The Futurists: The Aestheticization of War

Fig. 2. Stile futurista, 13-14, novembre 1935.

While, for the most part, artists had no interest in making public their opinions about colonial war, the Futurists’ infatuation with it is, by contrast, well known. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti had laid out his own colonial imaginary as early as his first literary efforts,5 and he found in the Ethiopian War the occasion to renew his predilection for extolling war. His best-known text on this subject remains, without doubt, L’estetica futurista della guerra, which was quoted by Walter Benjamin in his “Epilogue” to The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936). With this reference, the German philosopher completed his reflections on war, understood by him as the point of convergence for all efforts at the aestheticization of politics. Although the quotation is correct, L’estetica futurista della guerra, with its disturbing hymns to the beauty of war, did not appear in the daily paper La Stampa, as the philosopher had stated,6 but rather in issue no. 13-14 of the Turin review Stile Futurista, edited by Fillìa and Enrico Prampolini, where Marinetti had already published his Invito alla guerra africana (fig. 2).

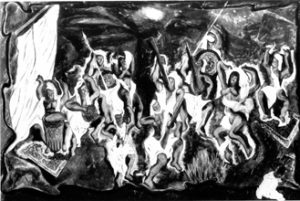

Fig. 3. Pippo Oriani, Fantaisie de Dubat, 1935, cm 180 x 220, lieu inconnu (d’après Enrico Crispolti, Il secondo futurismo : Torino 1923-1938, Torino 1961, p. 163).

The Futurists’ enthusiasm for the Ethiopian War had immediate consequences. The pictures exhibited during the 1936 Venice Biennale showed the state of Futurist pictorial language at that date. That pictorial language went from aeropainting (painting inspired by the modernity of aviation and the experience of flight) to what could be described as an attempt to revive battle painting. As concerns the colonial imaginary, an old reproduction shows us a picture of remarkable dimensions painted by Pippo Oriani in 1935, Fantasia di Dubat,7 which works in all the colonial stereotypes: men and women joined together in a frantic and savage dance to the beat of drums, a nocturnal scene evocative of a Witches’ Sabbath, and a world without any rules, as opposed to the civilized world, all of this simultaneously horrific and seductive (fig. 3).

Art Exhibitions and the Illustred Press

Art exhibitions were the place for the Fascist regime to engage in visual and spatial experimentation. In this regard, it suffices to recall the Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista, organized in 1932 with the cooperation, in particular, of Mario Sironi and Giuseppe Terragni. After the Ethiopian War, everything seemed to conform to the regime’s new “imperial” status (with the help of the bimillennium, in 1937, of the birth of Augustus) and to the new propaganda requirements set in place for the organization of exhibitions that advocated autarchy.

Abroad, the ambition to be Number One and, in the case of the Paris Exhibition of 1937, the eternal antagonism between Italy and France suggest that we should not underestimate the importance of modern language. Martini, Sironi, Gino Severini, Massimo Campigli—all the major Italian artists were there. But the way the rooms, and quite particularly the Salon of the Overseas Section, were arranged seems to have taken away that language’s power of seduction, which had descended into promotional platitudes. That is the reason why the salon arranged by Sironi was criticized by Waldemar–George, who was nonetheless a strong partisan supporter of Benito Mussolini and of the Fascist regime:

The Italians excel at photomontage; they had put it to excellent use during the much-talked-about Mostra della Rivoluzione, which took place in Rome a few years ago. We shall not make any mention, however, of the rooms devoted to the Ethiopian War. Is their presentation, both promotional and melodramatic, really worthy of the Empire? A Roman triumph is not a page from a magazine. A Roman victory is not a film.8

In a sense, Waldemar-George was not wrong. And yet, it was precisely in the pages or on the covers of magazines that the illustration of colonial history was laid out for a public that was as broad as it was heterogeneous. The illustrated press was the field for a vast elaboration of visual themes: the task of creating traditional drawings, but also that of the layout of photographic reports and photomontages, was often entrusted to artists, even the youngest ones among them, such as Bruno Munari. If, at the request of the Rivista illustrata del Popolo d’Italia (the illustrated weekly of the daily newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia, founded by Mussolini himself), Fortunato Depero executed a series of sketches for its special issue commemorating the proclamation of the Empire, the plurality of roles played by artists in the illustrated press cannot be underestimated. A veritable parallel history of art unfolds within those pages, a history that—as concerns Ethiopia—remains to be studied.

Notes

1 Italian Futurism, 1909-1944: Reconstructing the universe, ed. Vivien Greene (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2014).

2 On this topic, Dominique Jarrassé is preparing an article that is forthcoming in Studiolo.

3 Decree of November 11, 2011, Gazzetta Ufficiale, no. 11 (14 gennaio 2012). The decree was signed by the ministers of the the Berlusconi government in charge at the time of Foreign Affairs (Franco Frattini) and of the Economy and Finances (Giulio Tremonti).

4 Arturo Martini, letter to his wife, Milan [1935], in Le lettere di Arturo Martini (Milan: Charta, 1992), p. 177.

5 Mafarka the Futurist: An African Novel (London: Middlesex University Press, 1998).

6 On the gaps in the philosopher’s archives, see Walter Benjamin’s Archive: Images, Texts, Signs, trans. Esther Leslie, ed. Ursula Marx et al. (London and New York: Verso, 2007).

7 Enrico Crispolti, Il secondo futurismo: Torino 1923-1938 (Turin: Edizioni d’Arte Fratelli Pozzo, 1961), p. 163.

8 Waldemar-George, “Les pavillons étrangers à l’Exposition de 1937,” L’Architecture, 50 (August 15, 1937): 245-72 (see p. 265).

Bibliography

BARBIELLINI AMIDEI, Rosanna, et al. La casa madre dei mutilati di guerra. Rome: Editalia, 1993.

BENJAMIN, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin. Trans. Edmund Jephcott et al. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008.

CINELLI, Barbara, with Flavio FERGONZI, Maria Grazia MESSINA, and Antonello NEGRI. Eds. Arte moltiplicata: L’immagine del ’900 italiano nello specchio dei rotocalchi. Milan: Bruno Mondadori, 2013.

CRISPOLTI, Enrico. Ed. Nuovi archivi del futurismo. Rome: CNR/De Luca, 2010.

FERRARI, Claudia Gian with Elena PONTIGGIA and Livia VELANI. Arturo Martini (exhibition catalog). Milan: Skira, 2006.

LABBÉ, Edmond. Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques dans la vie moderne (1937), Rapport général, X. (Les sections étrangères, 2e partie). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1940.

MARGOZZI, Mariastella. Ed. Dipinti, sculture e grafica delle collezioni dei Museo Africano: Catalogo generale. Rome: ISIAO, 2005.

MARX, Ursula, with Gudrun SCHWARZ, Michael SCHWARZ, and Erdmut WIZISLA. Walter Benjamin’s Archive: Images, Texts, Signs. Trans. Esther Leslie. London and New York: Verso, 2007.

SCHNAPP, Jeffrey T., Anno X: La Mostra della Rivoluzione Fascista. Pisa: Istituti editoriali e poligrafici internazionali, 2003.