“Architecture in Uniform,” which is the title of Jean-Louis Cohen’s excellent exhibition at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine in Paris, presents projects both known and unknown that came into being between the Nazi’s destruction of Guernica in 1937 and the Allies’ atomic bombardments of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The interest of his academic research unit lies in its broad observational spectrum of countries that were engaged in the process of war in Europe, Japan, and the United States. For our seminar, he has agreed to discuss his methods of work and the reasons that drove him to relate gigantic projects as different as the Pentagon in the United States and Auschwitz and the Peenemünde Army Research Center in the territories annexed by the Reich and in Germany. What they have in common is that they all belong to a “modernization” process involving forms, techniques, and construction procedures.

Architects, draftsmen, and engineers played a major role in this process whose goal was to give efficient form to war factories from the Pacific to the Urals.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Architecture

en uniform

Jean-Louis Cohen

Between the destruction of Guernica by the Nazis in 1937 and that of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the Americans in 1945, many architects took part in the fight. The war called up all forms of their expertise, knowledge of construction techniques, visual knowledge, and organizational skills. Mobilized as a group, architects also were faced with personal choices, particularly so in the case of those called upon to participate in the criminal policies of the Nazis. In this sense, the war also tested their moral fiber. Some of them were complicit in extermination policies while others were to be counted among the victims.

As early as the 1920s, the writer André Maurois predicted that “The next war … will be so horrible that all who experienced this one will look back on it with regret. The cities in the rear will be completely destroyed by aerial attacks.” Indeed, the growth of aviation completely changed the previous distinctions between the battle front and the home front.

The chronicle of the war was thus punctuated by bombings whose intent was to terrorize civilian populations, with the first of these launched by the Axis forces: the Japanese flattened Chongqing and Shanghai, the Germans bombed Guernica, in the Basque country, then Rotterdam, and, during the Blitz of 1940, London. From 1942 on, some of the Allies engaged in their own aerial offensives, which would devastate German and Japanese cities as well as cities in occupied countries such as France or Italy.

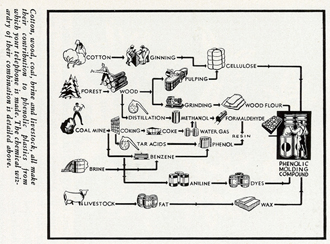

Much more than the Great War had ever done, World War II extended its hold far beyond the combat zones. The German writer Ernst Jünger had a premonition of this when, in 1930, he underscored “the rational structure and mercilessness” of the war of 1914-1918. Mobilization in the armed forces and in factories was coupled, de facto, with a requisition of dwellings. All mineral and agricultural raw materials as well as industrial materials were pressed into service for nations’ war efforts. The field of synthetic materials thus broadened from fuels to elastomers and to vast ranges of new products such as plastics.

The concern with conservation of materials entailed a new economics-based project ethic. Particular attention was paid to household energy consumption, which led to the launching of the first campaigns ever conducted in favor of thermal insulation.Factories in Time of War

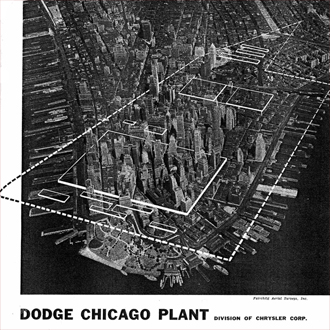

The construction of thousands of factories required for the production of aircraft, vehicles, and munitions summoned up, from the Pacific to the Urals, an army of project designers and draftsmen in which civil engineers and architects played leading roles.

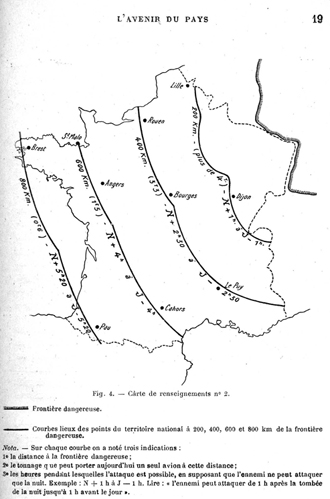

A striking phenomenon that extended trends from the 1930s was the emergence, in practically all countries, of a new industrial geography that was intended to reduce the risk of aerial attack by removing factories from countries’ borders.

Factories changed in scale and became groupings that sometimes attained the dimensions of genuine cities, employing tens of thousands of workers. Made necessary by the strict requirements of air-raid blackouts and made possible by the combination of lightweight span structures, air conditioning, and florescent lighting that allowed round-the-clock operations, the windowless factory dreamt up in the United States would give rise, after the war, to one of the most common building types found today on the outskirts of towns and cities: the Big Box that can be adapted to pretty much any use.

To house workers, it was in the United States that the most sweeping housing construction program was carried out. Enacted in 1940, the Housing Act, which took its name from Texas Congressman Fritz G. Lanham, allowed the massive use of Federal credits for housing construction. In addition to the number of housing units built through private initiative, 625,000 housing units would be produced between 1940 and 1944 under this law, 580,000 of which were temporary. Most of those units were destroyed starting in 1945.

War and Mobility

The mobility of the forces engaged in World War II far exceeded the levels of previous conflicts. The extension of the theater of operations to four continents involved intensive movement of men and their equipment, operating thousands of miles from their base.

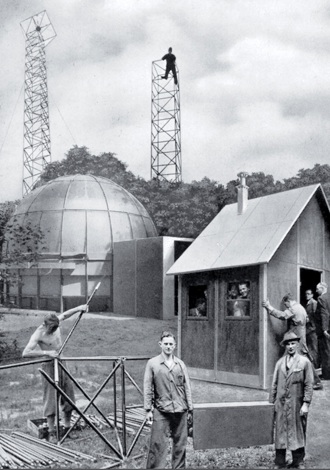

Architects therefore concentrated their inventive energies on the construction of lightweight modular structures, especially ones that could be assembled and disassembled. The prolific inventor R. Buckminster Fuller used the corrugated steel components of grain silos from the American Middle West to design the Dymaxion Deployment Unit that would shelter troops sent to the Persian Gulf in 1942-1943. The more radical experiments of Konrad Wachsmann and Max Mengeringhausen were to remain even more marginal.

The greatest successes came from those projects whose precision and simplicity allowed for industrial mass production. In the realm of building structures, there was the Quonset hut, widely used to shelter troops. As for infrastructures, modular bridges developed by Donald Bailey ensured Allied troops’ mobility within Europe, where 1,500 of them were assembled. And the greatest success of all, which played a decisive role in the Allies’ strategic victory during the Normandy landings in 1944, was the Mulberry artificial harbor, whose components were transported by sea from England. As Albert Speer would later admit, this ingenious device rendered the Atlantic Wall inoperative by itself alone.

Shelters and Camouflage Against Aerial Threats

While danger from the air had already made itself felt during World War I, though then only in a relatively modest fashion, this menace took on new dimensions in the 1930s. Modern architects would not take long to show an interest in this new set of architectural and urban issues.

In 1942, Salvador Dalí wrote that the “War of Production” had to be coupled with a war of “magic.” This consisted in an effort to conceal armed forces, factories, and even whole cities from the view of enemy aviators in which one had to call upon the visual skills of architects and landscape artists.

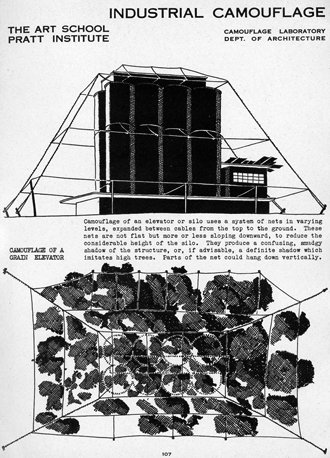

Each warring nation set up a camouflage service, which sometimes led to extremely sophisticated research into daytime and nighttime perception of landscapes and into the effects of sunlight or cloudy skies because of the potentially crucial role of shadows. A truly scientific approach to architecture was emerging at that time, and it was followed up with rigorous field-testing procedures.

This work was pursued on every scale, from the concealment of a single gun battery, command post, or isolated bunker to the apparent displacement of an entire city. The well-known project for a “fake Paris”—imagined in 1918 to confuse German zeppelins—inspired spectacular ventures, as at Hamburg, where a large-scale operation began in 1941 to “displace” visually a portion of the city center.

Architectural Giganticism

In a 1944 text on “Bigness and its Effects on Life,” the German urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, who was then teaching in Chicago, stated that “the main trend of our time is toward bigness.” This trend was particularly evident in industrial production, logistics, and the conduct of the conflict.

Large buildings were themselves set within quite vast territorial networks. In Washington, the Pentagon was the central point in an extensive system of highways and parking lots. The atomic facilities at Oak Ridge were made possible at this site only because they were connected to the hydroelectric facilities of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The same held true for Soviet industrial projects east of the Urals and, especially, for Nazi projects. Thus, the Auschwitz camp was but one component in a great industrial conglomeration situated at the intersection of rail lines linking it to Europe as a whole.

In order to design such systems, teams of architects were assembled on an unprecedented scale, these teams operating within civilian and military administrations or in the form of private agencies, such as the firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, whose unstoppable growth began with the project for the town of Oak Ridge in Tennessee.

The Postwar Period: A World Transformed

The deadliest conflict in human history came to an end with the capitulation of Japan on September 2, 1945. The war did not only leave behind millions of dead and millions of traumatized survivors, as well as thousands of cities in ruins. It also fundamentally transformed human practices, from science and technique to culture.

Architecture was no exception to these changes that affected all societies. In the six years of the War, the scale of projects had been altered, new materials appeared, and, with them, ideas for the industrial production of housing and public edifices, which had been imagined prior to 1939, now became tangible possibilities. Questions that had been rejected by modern architects, such as the issue of monumentality, became vital features of public debates when the commemoration of sacrifices and victories proved to be a necessary task.

A cultural transformation also took place for all those men and women who had encountered the new technologies: soldiers reverting to civilian life after having used airplanes, Jeeps, and walkie-talkies and women returning to their homes after having worked in industrial production no longer had the same expectations and were ready to accept new materials and modern architectural solutions to housing issues.

Aside from the plans for reconstruction, which had occupied European architects as early as 1941, and their implementation, which would extend into the mid-1950s, housing studies relied on the results of research conducted during the War. Thus was heralded a new, more objective form of practice.

- 1. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Vauthier, “Courbes des points du territoire national [situés] à 200, 400, 600 et 800 km de la frontière dangereuse,” in Le Danger aérien et l’avenir du pays (1930). Collection of the author. All rignts reserved.

- 2. Agricultural-based plastics production, in E. F. Lougee, Plastics from Farm and Forests (1943). Collection of the author. All rights reserved.

- 3. Albert Kahn Associates, Dodge Aircraft Factory, Chicago, 1943. Superimposition of the factory’s blueprint on an aerial view of Manhattan; illustration printed in The Architectural Forum, December 1943. Collection of the author. All rights reserved.

- 4. Mulberry artificial harbor at Arromanches. Landing of a convoy of ambulances, September 1944; illustration printed in L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, 2 (1945). Collection of the author. All rights reserved.

- 5. Max Mengeringhausen, the MERO system. Examples of use proposed in 1943; illustration printed in Raumfachwerke aus Stäben und Knoten, 1975. Collection of the author. All rights reserved.

- 6. “Camouflage of a Grain Elevator,” plate by Konrad F. Wittmann, Industrial Camouflage Manual, 1942. Collection of the author. All rights reserved.

- 7. George Edwin Bergstrom, David Witmer. Bâtiment du Département de la Guerre (Pentagone), Arlington, Virginie, 1941-1943, vue aérienne générale, 1953 ; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington. All rights reserved.

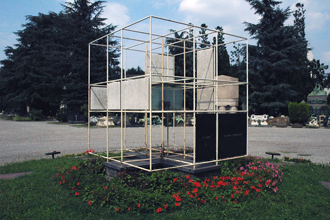

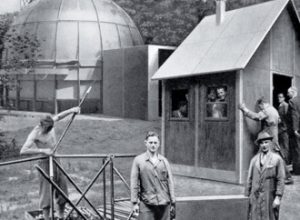

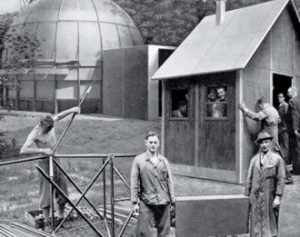

- 8. Walter Schlempp, power station, Peenemünde rocket base, c. 1942. 2011 photograph by the author. All rights reserved.

- 9. Lodovico Barbiano di Belgiojoso, Enrico Peressutti, and Ernesto Nathan Rogers, Monument to the Victims of Nazi Concentration Camps, erected within the Cimitero Monumentale di Milano, 1946. 2005 photograph by the author. All rights reserved.

Bibliography

ALBRECHT, Donald, World War II and the American Dream. How Wartime Building Changed a Nation, Washington, Cambridge, Mass., National Building Museum, MIT Press, 1995.

BOSMA, Koos, Shelter City: Protecting Citizens Against Air Raids. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

COHEN, Jean-Louis, Architecture in Uniform: Designing and Building for the Second World War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

DECKER, Julie, and Chris CHIEI. Quonset Hut: Metal Living for a Modern Age. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2005.

GOODEN, Henrietta. Camouflage and Art: Design for Deception in World War 2. London: Unicorn Press, 2007.

GUTSCHOW, Niels. Ordnungswahn: Architekten planen im “eingedeutschten Osten” 1939-1945. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann and Bâle, Boston, and Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2001.

GUTSCHOW, Niels and Jörn DÜWEL. Eds. A Blessing in Disguise: War and Town Planning in Europe 1940-1945. Berlin: DOM Publishers, 2013.

SHANKEN, Andrew M. 194X: Architecture, Planning, and Consumer Culture on the American Home Front. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

VIRILIO, Paul. Bunker Archeology: Texts and Photos (1975). Trans. from the French by George Collins. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994.

VOLDMAN, Danièle. Reconstruction des villes françaises de 1940 à 1954: histoire d’une politique. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997.