Nicholas-Henri Zmelty defended a noted thesis (winner of the Orsay Museum Prize) on France’s ca. 1900 poster craze. Here, he looks at the mass-circulation illustrated press in France, investigating its strong links with prewar culture from the standpoint of heroic, erotic, and humorous representations.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Nicholas-Henri ZmeltyThe Great War

of Images

Between 1914 and 1918, the French illustrated press gave to the War a highly uneven visibility. We propose to take a look at this form of mass production by analyzing it thematically and investigating its connections with prewar culture. The heroic, humorous, and erotic representations found in the press at the time the Great War are examined here through a study of drawings from the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, Le Rire rouge, and Sourire de France. While their respective editorial lines did not preclude a mixing of genres, each of these three newspapers, taken individually, can be considered to be emblematic in its own way for the treatment of the issues of the patriotic heroism of soldiers, humor, and eroticism in time of war.

Expressions of Heroism in the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal

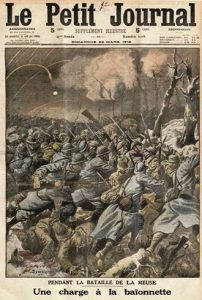

Damblans, “Pendant la bataille de la Meuse. Une charge à la baïonnette [A bayonet charge during the battle of the Meuse],” Le Petit Journal supplément illustré, 1318 (March 26, 1916). Private collection.

For the entire duration of the War, its readers were overexposed to a multitude of images of the fighting that can be counted among the most stereotypical ones in the genre. The bayonet charge and hand-to-hand combat inspired many heroic scenes from Damblans, the near-exclusive illustrator for this paper during the first three years of the War, as well as from his collaborators and from his successors. Fantastical on more than one score given the new realities modern warfare had ushered in, these images fit into a tradition of offering representations that condition the expectations of readers-viewers. Indeed, what the gaze of 1914 clearly evinces is a strong familiarity with artworks and with other images in all genres that, prior to the War, had celebrated the valor of the Revolutionaries of 1792, of Napoleonic troops, and of the soldiers from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871. The Great War could not help but boost production of representations of this kind. Completely unrealistic images, their sole purpose was to convince public opinion of the unfailing courage of the fighters on the front. The patterns of composition are often identical, the uprightness and striving power of the massed lines of French soldiers contrasting with the horizontality and shapeless collapse of the German troops. Numerous pictures of battle were able to serve as the standard, with Anne-Louis Girodet’s Revolt in Cairo (1810) being among the most graphic examples.

When one looks closely at the drawings published in the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, the French soldiers who plunge into the fray at the risk of their lives seem invincible. Death, when it is given figural form, mainly strikes the Germans. Most often, the French are only wounded, sometimes grievously, but always at the cost of some heroic act. Generally speaking, representations of death are rather toned down in order to appear in an acceptable light. Whereas some photographs published in such weeklies as Le Miroir might reveal some truly horrific scenes (decapitations, amputations, and so on), the countless costs modern weaponry inflicted upon combatants’ bodies do not appear in newspaper drawings. What did one want to mask? Civilians, in particular the readers of the Petit Journal, were nonetheless already habituated to the bloody and macabre front pages, with a strong taste for the sensationalistic, that the weekly had published prior to the War.

Neither was the mental devastation brought about by the “great slaughter” considered admissible in the satirical press. That was not the case for representations of heroics, though they were less numerous than in such mass-circulation papers as Le Petit Journal, L’Illustration,or Le Pays de France. In this regard, the cover for the August 12, 1916 issue of Le Rire rouge is exemplary: in a nearly dreamlike vision, Adolphe Willette offered the hallowed image of a father who, before going into action, waved his hand toward his wife and his child in a way that resembled a kind of blessing. The obvious connections with the Christian iconography of Christ giving his blessing, of saints, and of martyrs underscore the multiplicity of sources for wartime drawings, including in humor magazines.

Before dealing with the topic of caricature at Le Rire rouge, let us point out that caricature also had it place in the pages of the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal. That being said, just as with scenes of combat or allegories, this newspaper’s comics all came out of one and the same fantastical mold. Left back at the home front, its illustrators imagined the War more than they had any actual experience of it. And whatever the degree of knowledge they might have had of the realities on the front—supposing that they would have wanted to bear witness to them—the Petit Journal could hardly serve as a platform for them to express their views, on account of censorship. Finally, whereas prior to the War, what the front pages of the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal related above all were trivial news items chosen for their sordid or spectacular aspects, during the Great War they resorted, rather, to expressing very general views or ideas. At the expense of actually informing people, these images no longer served to fill in readers-viewers about current events but instead served to galvanize morale on the home front and to maintain the war effort.

Caricatures in Le Rire rouge

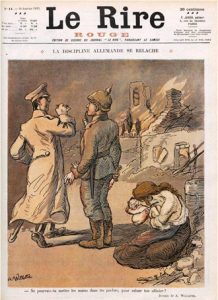

Adolphe Willette, “La Discipline allemande se relâche [German discipline slackens],” Le Rire rouge, 11 (January 30,1915). Private collection.

The comics, too, were involved in this mobilization of people’s minds. In an article on wartime caricature published in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1921, André Blum spoke of an “art of killing the enemy through ridicule.” The cartoonists of Le Rire rouge took part in this vast undertaking of demolition through mockery by targeting the characteristics of German identity one enjoyed lumping together back then under the term Kultur. Mores, education, women, fashion, gastronomy, the arts, politics, and, of course, Kaiser Wilhelm II and his sons were inexhaustible sources of inspiration for French satirical cartoonists.

Here again, the patterns are the same as before the War; only the scapegoats had changed. In 1899, a special issue of the paper Le Rire entitled V’la les English!, which was wholly illustrated by Willette, dragged through the mud all the faults of what was still called “perfidious Albion.” Le Rire rouge being the wartime edition of Rire, the humor of its collaborators simply adapted itself to the changed circumstances. The so-called caricature of manners thenceforth served to rally the home front. Sometimes, one waxed ironic in a virulent way about those labeled shirkers. Moreover, visceral hatred of the enemy stimulated the satirical press and the drawings were sometimes exceptionally violent.

While several of its illustrators took pleasure in denouncing the brainwashing practiced elsewhere in its pages, Le Rire rouge was not an exception on this score: the gross exploitation of rumors about atrocities supposedly perpetrated by German troops during the invasion of 1914—and in particular the myth of children with their hands cut off—places Le Rire rouge among the great propagators of lies. The drawings published by this paper and its main rivals, such as La Baïonnette and Fantasio, contain a peculiar form of propaganda that could be described as patriotic self-mockery. The French soldier was indeed praised for his outlandish fancies and his jocularity—which, in the end, made him superior to his enemy.

In the case of German propaganda, these clichés were used for discriminatory ends: the French were said to be too carefree, too lazy, and, ultimately, too cowardly to fight with dignity. As if engaged in an operation of national autosuggestion, the effect of the overrepresentation of quietly joking soldiers enamored of witticisms and capable of waxing ironic about the ordeals with which they were confronted was to keep one’s distance from, even deny, one’s fear and the omnipresence of death. In the drawings from Le Rire rouge, the horrors of war were hidden by the power of humor and a cheerfully blithe attitude, two “weapons” with which the French were said to be naturally endowed.

The Erotic Drawings of Le Sourire de France

A. Guyon, “Devant la glace . . . [In front of the mirror],” Le Sourire de France, 41 (January 24, 1918). Private collection.

More classical still are the “album pages” printed on a paper slightly heavier than the rest of the publication, and which were meant to be collected as a compendium of erotic images. These drawings are no more nor less than variations on studies of academic nudes, to which the artists added a few contemporary accessories in order to intensify their power to evoke fantasies.

Here again, as in the combat scenes for the Supplément illustré du Petit Journal, it is interesting to note to what extent these nudes were thoroughly anchored in an old iconographic tradition. Through their postures and through their poses, the charming young ladies peeling off their clothes or lounging around in the privacy of their bedrooms are reminiscent in many respects of nymphs, Venuses, and other effigies that have been, since Antiquity, so many odes to female beauty. In Le Sourire de France, everything becomes a pretext for unveiling their nudity: allegories, variations on paintings showing the various times of the day, scenes of bathing, dressing, and undressing, various and varied fantasies, and so on. This very conventional eroticism comes close to the saucy pages of the Belle Époque. Indeed, it may be noted that the illustrators for Le Sourire de France barely shifted at all what they produced in connection with the war context. The very existence of the War, its presence in daily life, was often conveyed in quite anecdotal fashion, for example in the form of a simple object like a helmet that, when sported by some ravishingly beautiful and sassy young girl, saw itself reduced to a sort of fashion accessory. Beneath the thrusts of love, war is no longer anything but ornamental.

Bibliography

ALEXANDRE, Arsène. Pendant la guerre. L’esprit satirique en France. Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1916.

AUDOIN-ROUZEAU, Stéphane and Annette BECKER. 14-18, retrouver la guerre. Paris: Gallimard, Folio, 2000.

BECKER, Jean-Jacques, Jay M. WINTER, Gerd KRUMEICH, Annette BECKER, and Stéphane AUDOIN-ROUZEAU. Eds. Guerre et cultures 1914-1918. Paris: Armand Colin, 1994.

BLUM, André. “La caricature de guerre en France.” Gazette des Beaux-arts, 1 (1921): 237-54.

DEMM, Eberhard. “Propaganda and Caricature in the First World War.” Journal of Contemporary History, 28 (1993): 163-92.

GERVEREAU, Laurent, and Christophe PROCHASSON. Eds. Images de 1917. Paris: Musée d’histoire contemporaine, BDIC, 1987.

GRAND-CARTERET, John. Caricatures et images de guerre. La Kultur et ses hauts faits. Paris: Librairie Chapelot, 1916.

LA SIZERANNE, Robert de. “La Caricature et la guerre.” Revue des Deux mondes (June 1-15, 1916): 481-502 and 806-41.

NAVET-BOURON, Françoise. “Censure et dessin de presse en France pendant la Grande Guerre.” Guerres mondiales et conflits contemporains,197 (2001): 7-19.

VATIN, Philippe. Fonctions des arts graphiques en France pendant la Grande Guerre. Art History Dissertation, University of Paris-I, 1984.