Thibault Boulvain studies here the work of Kader Attia, whose recent efforts are of fundamental importance for our reflections on how the events of colonial times and transfers between the African continent and the European one are committed to memory. Through his work, Attia investigates art’s role as the site within which conflicts are revealed but also as the one wherein they might be resolved for both artists and viewers.

Laurence Bertrand Dorléac

Thibault BoulvainThe Repair from Occident to Extra-occidental Cultures

Reinvention and Reconstruction in the Work of Kader Attia

The problem of “repair [réparation]” runs through the art of Kader Attia (b. 1970) for now going on a decade and a half. His interest began when one of his friends offered him some African material patched up with the help of a piece of Vichy fabric. Intrigued by this mending job, Attia developed an interest in African objects (masks, statuettes, and various other items) “repaired” in this way and preserved today in the greatest museums of the Western world. He was then able to observe that such objects either are rare there or are exhibited in such a way that their repairs remain largely hidden. For Attia, this de-monstration or occultation is the sign of the real difficulty the European scientific community experiences when thinking about such objects: integrating exogenous elements into their original creative context (buttons, fabrics, or coins from colonial society), they thus elude the reassuring taxonomies of Art History. The second stage, for Attia, was to look into the chronology of the reception of these African objects in Europe and to develop, on this basis, a basic postulate that now guides his work: according to the artist, around the turn of the Twentieth Century, when these “repaired” objects arrived in Europe (where they were considered crude, incomplete, formless, bastardized), the West was engaged in a quest for a kind of ideal of formal and aesthetic perfection, of which World War I constituted perhaps, paradoxically, the acme.

Disfiguration

1. Kader Attia, The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, dOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Fridericianum, June 9-September 16, 2013.

Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA 13 with the support and courtesy of Galleria Continua, Galerie Nagel Draxler, Galerie Krinzinger. Further support by Fondation nationale des arts graphiques et plastiques, France; Aarc—Algerian Ministry of Culture.

A vast immersive installation presented during documenta 13 in Kassel, The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures sets up a confrontation between thoughts and practices of “repair” from one continent to another, from one culture to another, and from one time to another. Haunted by the specter of the Great War, this work invites the viewer to reevaluate the concept of perfection, particularly through the prism of the issue of disfiguration.

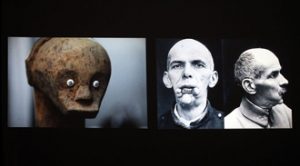

The Repair effectively brings out the way in which efforts at “repair” obey, depending on whether the culture is Occidental or extra-Occidental, one or another of two antagonistic logics. In Africa, Attia recalls, in the same way that scarifications or corporeal distortions pertain to aesthetic strategies for completing a body judged imperfect, the repair of an object is part of the process of its embellishment, thereby allowing it to be reborn and offering it a new future. Because it pertains to an invention of new forms, to a reinvention of the object, the repair in question has to be visible and must be affirmed in its full materiality. In Western cultures, on the contrary, the ideal of perfection requires that it be dissimulated as much as possible. During World War I, as Attia emphasizes, reconstructive surgery, which was then undergoing great developments, thus strove to erase from shattered faces the stigmata of war. It was the job of surgeons to bring back one’s original, intact, ideal countenance [figure]. The “broken mug” [gueule cassée][1] was to be repaired, one’s visage was to be brought back, with all traces wipe away.

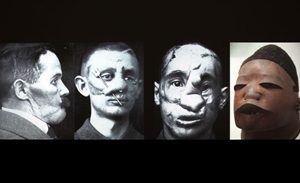

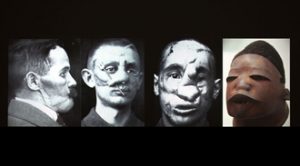

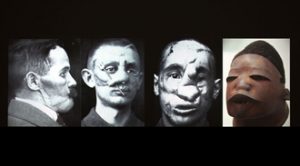

2. Kader Attia, The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, dOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Fridericianum, June 9-September 16, 2013. Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA 13 with the support and courtesy of Galleria Continua, Galerie Nagel Draxler, Galerie Krinzinger. Further support by Fondation nationale des arts graphiques et plastiques, France; Aarc—Algerian Ministry of Culture. Still (detail of video slide show).

In the comparisons and confrontations Attia establishes between African objects and repaired “broken mugs,” the emphasis is indeed placed on the development, during the War, of the techniques employed for the repair of bruised bodies. Thus, the artist underscores the fact that, from an almost “artisanal” form of repair that, at bottom, was quite close to the kind done for African objects—wherein sutures still furrow disfigured brows and reconstruction sometimes increases the disfiguration—little by little the transition was to a much more subtle, more “discreet,” so to speak, form of repair, taken as a symbol of progress and modernity nevertheless belied by the barbarity on the fields of battle.

The body at war, wounded in its flesh, mutilated, interests Attia because its disfiguration is a blow struck against identity itself. Set at the heart of The Repair’s visual apparatus, the motif of the scar poses the problem of its representation and of its “showability,” of its acceptance as well as its rejection, of its signification as well as of the stakes involved. Two decades before Attia, Sophie Ristelheuber, upon returning from a stay in Yugoslavia (July 1991), did a show entitled “Every One” in a Parisian hospital; it consisted of fourteen, very large-format photographs of bodies, each one marked by a recent suture, like so many allegories of the Serbo-Croatian conflict.

Being the Other

While The Repair binds man and object, the animate and the inanimate, the carnal and the material into one and the same reflection on the concepts of repair and perfection, Paul Ardenne recalls that, when set at the heart of documenta 13, this work was basically for Attia a matter of reflecting (and getting others to reflect) on “two ways of shaping human beings that are presented . . . in simultaneous and spectacular fashion,” the one as well as the other referring back, perhaps, to “a diametrically opposed representation of human beings—the metaphysical dimension for the African mask; the death drive and barbarity for the ‘broken mug.’” [2] Most certainly, the “proximity, in terms both of the plastic arts and of symbolism,”[3] between, especially, the African mask and the “broken mug”—which had already been picked up on by the Surrealists in their time, in particular by Georges Bataille in Documents—forces us to reevaluate another concept Attia places at the center of his reflections: barbarity.

While in the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries, the aesthetic of the African mask or of the fetish object signified, for Europeans, the irreducible alterity, nay even the intrinsic savagery, of the Other, of the “uncivilized,” the Great War itself, Sigmund Freud recalled in 1915 in his Thoughts for the Times on War and Death, revealed the barbarity in what is civilized. War, wrote Freud, is that moment when people thought they could “withdraw for a while from the constant pressure of civilization and to grant a temporary satisfaction to the instincts which they had been holding in check”; it “strips us,” he says, “of the later accretions of civilization, and lays bare the primal man in each of us.”[4] The Repair now requires a decentering of our gaze and opens up our sometimes blinded eyes: in this vast space for reflection created by Attia, who in reality is the “Civilized” and who is the “Barbarian”? The “Savage” is, at bottom, undoubtedly not the one thought to be so, but the one who hides less behind African masks, the artist suggests, than behind the masks of flesh of the victims of the Great War.

Mutilated Memories

Scars and their repair are, in Attia’s work, also memory laden. His entire oeuvre affirms a conflict-ridden cultural identity, and he champions as a model of artistic commitment Émile Zola’s “J’accuse.” Attia believes in both art’s redemptive power and its capacity to make us reflect on the impasses to which our ways of thinking lead us. For this Franco-Algerian artist whose oeuvre constantly investigates “geographical or religious collisions, cultural and social contradictions, memberships in complex identities, globalization, and ethnic breakdowns,”[5] his work is itself “an analyst’s couch.”[6] “I use the medium of art,” he says, “to say political things but also as a psychoanalytic prop. I like the idea that art might be able to be a kind of psychotherapy for the artist as well as for the viewer.”[7]

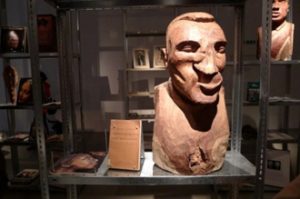

3. Kader Attia, The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, dOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Fridericianum, June 9-September 16, 2013.

Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA 13 with the support and courtesy of Galleria Continua, Galerie Nagel Draxler, Galerie Krinzinger. Further support by Fondation nationale des arts graphiques et plastiques, France; Aarc—Algerian Ministry of Culture. Still (detail of the installation).

At documenta 13, The Repair offers the artist a way of trying to accelerate the memory process, which, since the outset, has been set at the heart of the artist’s discourse and project. Here, in Germany (where modern and extra-Occidental art were condemned in 1937 as “degenerate”), within the symbolic space of one of the world’s most celebrated exhibitions of modern and contemporary art, various (Western) works in the History of Art are placed on the shelves that go to make up this installation. They remind the visitor to what extent European artistic imaginaries were fertilized by the so-called primitive arts and how modernity itself was defined in part with the aid of those contributions. “A whole nourished by collected images, newspaper clippings, posters, documentary films, and statuettes, [The Repair] constitutes, without any doubt,” writes Paul Ardenne, “the ultimate monument for the debt the West has contracted with countries that, not so long ago, were vassals still held in its colonial yoke.”[8]

4. Kader Attia, The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, dOCUMENTA 13, Kassel, Fridericianum, June 9-September 16, 2013.

Commissioned and produced by dOCUMENTA 13 with the support and courtesy of Galleria Continua, Galerie Nagel Draxler, Galerie Krinzinger. Further support by Fondation nationale des arts graphiques et plastiques, France; Aarc—Algerian Ministry of Culture. Still (detail of video slide show).

Frustrating, moreover, our traditional reading of cultural transfers and exchanges between the African and the European continent, Attia has asked contemporary African sculptors to execute for the exhibition some busts of people with “facial wounds,” done on the basis of photographs. This is a way for the artist to make it known that, while the great Moderns of Western Art History were able to gaze at the Other, this Other today casts, in return, his own gaze on Western Man in all his destructive savagery. It is also a way of recalling that those with “broken mugs” were not only Europeans and that colonized Africa, too, laid its dead on the altar of war.

As “the ultimate monument for the debt” the West owes Africa, The Repair is a memorial museum that functions as a space of historical memory. Through his environments, installations, photographs, drawings, and videos, a memory of war and, especially, of colonization returns, crushingly, obsessively, in all of Attia’s work. Because art can also pacify—the living, surely, the dead, perhaps—and because it can treat wounded souls, but especially because it can repair, that is to say, do justice and render justice, Attia attributes to it a central role in the rewriting of a history and a memory. In this sense, The Repair, along with some of the artist’s other productions, exemplifies, in the field of art, what Jack Goody was denouncing in 2006 in his militant essay The Theft of History.[9] Because this work arrives after the break-in and the theft, the wound, in Attia’s work the act of repair is a process of restitution, of reappropriation of what was or remains stolen: an identity, a history, a memory, all of which have been mutilated. It is, in short, a reinvention of our gaze on the world of yesterday, of today, and of tomorrow. It is also a promise—of reconciliation between cultures and men.

Notes

[1] ARDENNE (Paul), « dOCUMENTA (13). Générosité ambiguë et pulvérisation de la culture »,

http://paulardenne.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/documenta-13-texte-paul-ardenne.pdf (page consultée le 7/10/2013).

[2] Idem.

[3] FREUD (Sigmund), “Considérations actuelles sur la guerre et la mort”, in Essais de psychanalyse, Paris : Payot, 1981, 277 p. Petite bibliothèque Payot; P15. Pp. 248 et 266.

[4] LAMY (Frank), LÉGER (Stéphane), Émoi & moi, exposition présentée au MAC-VAL (musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne) de Vitry-sur-Seine du 23 février-19 mai 2013, Vitry-sur-Seine : MAC-VAL, 2013, 256 p. P. 13.

[5] ROCHEBOUËT (Béatrice de), “Kader Attia dans l’œil des musées”, Le Figaro, 17 juin 2006.

[6] SAUSSET (Damien), “Kader Attia face aux fractures du monde”, Connaissance des arts, juin 2006, pp. 63-66. P. 63.

[7] ARDENNE (Paul), « dOCUMENTA (13). Générosité ambiguë et pulvérisation de la culture », art. cit.

[8] GOODY (Jack), Le vol de l’histoire. Comment l’Europe a imposé le récit de son passé au reste du monde, Gallimard, 2006, 496 p.

Bibliographie

AUPETITALLOT (Yves), PRATT (Thierry), Kader Attia, exposition présentée au musée d’art contemporain de Lyon du 15 juin au 23 août 2006 et au Magasin, Centre national d’art contemporain de Grenoble du 21 octobre 2006 au 7 janvier 2007, Zurich, JRP Ringier, cop. 2006, 110 p.

DURAND (Régis), ZAYA (Octavio), FELDMAN (Hannah), Kader Attia, exposition présentée au Centro Huarte de Arte contemporeano du 4 juillet au 28 septembre 2008, Huarte, Centro Huarte, 2008, 190 p.

La critique à l’œuvre : Xavier Velhan, Mathieu Mercier, Kader Attia, Claude Lévêque, Annette Messager, Fabrizio Plessi, Daniel Depoutot, textes des étudiants du Département Arts visuels de l’UFR Arts de l’Université Marc Bloch (Strasbourg), Strasbourg, Université Marc Bloch, 2007, 85 p. Cahiers-chroniques.

FREUD (Sigmund), “Considérations actuelles sur la guerre et la mort”, in Essais de psychanalyse, Paris, Payot, 1981, 277 p., Petite bibliothèque Payot, P15.

FROGIER (Larys), Ouvertures algériennes/Réactions vivantes : Kader Attia, Khaled Belaïd, Farid Redouani, Samira Sahnoun, Zined Sedira, exposition organisée à La Criée, Centre d’art contemporain de Rennes du 6 juin au 14 août 2003, Rennes, La Criée, Centre d’art contemporain, 2003, 62 p.

LAMY (Frank), LÉGER (Stéphane), Émoi & moi, exposition présentée au MAC-VAL (musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne) de Vitry-sur-Seine du 23 février-19 mai 2013, Vitry-sur-Seine, MAC-VAL, 2013, 256 p.

RENARD (Emilie), “Kader Attia : à double détente”, Beaux-arts magazine, décembre 2006, p. 61-63.

ROCHEBOUËT (Béatrice de), “Kader Attia dans l’œil des musées”, Le Figaro, 17 juin 2006.

SAUSSET (Damien), “Kader Attia face aux fractures du monde”, Connaissance des arts, juin 2006, p. 63-66.

Thibault Boulvain prépare actuellement sous la direction de Philippe Dagen (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) une thèse de doctorat intitulée « Un ‘‘art malade’’. Pratiques et créations artistiques au temps des ‘‘années sida’’ (1981-1997). États-Unis/Europe ». Assistant pour la préparation de l’exposition « Les désastres de la guerre » (Louvre-Lens, 28 mai-6 octobre 2014), il a rejoint en octobre 2013 l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art en tant que chargé d’études et de recherche au sein du domaine « Histoire de l’art contemporain, XXe et XXIe siècles ».