Home>GROWING TOMATOES IN THE DESERT

12.06.2024

GROWING TOMATOES IN THE DESERT

What the UAE’s vision to address the sustainability challenges it faces teaches us about the link between (environmental) constraints and innovation

By Hermine Durand

Since the 2010s, Dubai’s International Airport (DXB) has consistently been in the world’s top 5 busiest airports by international passenger traffic. Ranking alongside major aerial hubs like Atlanta, Dallas, Chicago, New Delhi, Los Angeles, London, Beijing, and Istanbul, Dubai’s airport ensures connections to 262 destinations across 104 countries (Emirates 24/7, 2017). In 2023, the airport welcomed 86.9 million passengers, almost equivalent to its pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels (Reuters, 2024).

Upon landing in DXB, all these passengers probably also remarked the three elements that, set aside jet lag, most striked the LX members right as they stepped out of the plane: in the airport, we immediately noticed the hot and humid weather, but also the palm tree rows complementing a lavish indoor garden, and the monumental waterfall’s endless stream in the arrival hall.

Hence, Dubai’s newcomers are welcomed by a seemingly paradoxical cocktail of equally abundant plants, water, and desert heat. This intrigue further grew as we woke up on our first morning in Dubai and gazed at the city’s skyline, noticing, far beyond myriads of skyscrapers and urban constructions, a light “desert sand halo” at the horizon. Although initially inconspicuous, we came to the realization that these first sensorial impressions of Dubai encapsulated some of the city’s main ecological and sustainability challenges. From scorching summer heats, all-pervading urban shade arrangements, air conditioning and indoor-centered activities, to occasional dust and sand storms (Duncan, 2022): Dubai’s environmental reality is impossible to overlook. The desert is omnipresent.

But it’s only during our visit to Pure Harvest that we truly got a taste of Dubai’s desert-born miracle. As the smart farm startup’s CSO Lucio Baron greeted us with fresh and luscious tomato and blackberry punnets, the multi-stakes of Dubai’s environment became more concrete. Grown in the desert, these fruits as well as Pure Harvest’s entrepreneurial journey illustrate the UAE’s approach to local and global climate challenges.

How does the UAE strive to ensure its sustainability amidst its challenging desert environment? What role does innovation play in this strategy? What can this approach teach us about entrepreneurship?

The UAE’s Sustainability Challenges: Navigating Water and Food Insecurity in a Changing Climate

“Like a Middle Eastern version of Las Vegas, Dubai’s biggest challenge is water, which may be everywhere in the gulf but is undrinkable without desalination plants” notes Alderman (2010).

In fact, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, including the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries - the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia - is distinguished by its unique geoecological profile, marked by arid and semi-arid climates, vast expanses of desert, and limited water resources.

This environmental backdrop presents substantial ecological and sustainability challenges such as water scarcity, import-dependent food security, population concentration in urban centers, and swift urbanization.

Water scarcity is a major issue due to the arid climate, but it is also exacerbated by the rapid urbanization rate, and increasing water demand for industry, domestic and agriculture use. The UAE's reliance on desalination plants for freshwater further aggravates energy consumption needs, contributing to carbon emissions and environmental degradation. Moreover, the massive development of cities like Dubai have also led to habitat loss, biodiversity depletion, and increased air and soil pollution, posing threats to local ecosystems and wildlife. Hence, while in 1961 the UAE disposed of 1,063.95 metric cubes of domestic renewable freshwater resources per capita, this number decreased to 147.92 by 1980 (-86.1%) and 16.28 by 2019 (-98.5%).

Food security, defined by the 1996 World Food Summit as the condition where “all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life,” is another critical challenge (FAO, 2009).

With only 4.6% of the land surface being used for agriculture in 2018 in the UAE, of which a mere 0.5% is arable land, this harsh environment and lack of resources for agriculture limit domestic food production, thereby hindering food self-sufficiency and sovereignty (Pirani & Arafat, 2016; Shah, 2010). Hence, despite their wealth, GCC countries are among the world's most food deficient and water-insecure regions, with imports covering up to 90% of domestic food needs (Ali, 2022). This dependence on external food sources poses significant risks to food security, as seen during global supply chain disruptions or the 2007/2008 and 2010/2011 food price crises (Hubbard & Hubbard, 2013).

These resource risks are further compounded by the region's socio-economic dynamics. The UAE and more generally the GCC, hold a pivotal role in the global energy landscape. Between 2013 to 2022, the UAE produced an average of about 2.9 million b/d of crude oil (US IEA, 2023). Ranking as the 5th largest hydrocarbon energy producer within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the 6th largest exporter in 2023, it contributes to at least 55% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) (Ajaj et al., 2019). Coupled with the highest population growth rate in the region, the consequent surge in demand for not just electricity but also water complexifies the resource challenges faced by the UAE (Samara Bin Salem & Premanandh Jagadeesan). With nearly 85% of the population residing in the three largest emirates - Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Sharjah - population pressure in urban centers stiffles ressource stress. Lastly, the UAE’s significant reliance on hydrocarbon exports, also introduces additional layers of vulnerability to global market fluctuations.

With rising temperatures, erratic rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme weather events threatening water resources and agricultural productivity, climate change exacerbates all the stakes. Therefore, strategic government planning, sustainable practices, and technological innovations towards conservation and adaptation appear crucial to ensure the UAE’s resilience and help mitigate these risks.

How the UAE is Harnessing Innovation to Overcome Environmental Constraints

Marcus Aurelius is known to have theorized that “the impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way”.

In light of the UAE’s development pattern in the past 50 years, it seems that this philosophy could pertinently apply to the country and its approach to tackling environmental and sustainability constraints. Despite arid climates, limited natural water sources, and a dependency on hydrocarbon exports, the UAE, and particularly Dubai - as underscored by its evolution from a pearl-diving base to a global hub for innovation, tourism, and services - seems to constantly seek a pathway for transforming environmental constraints into opportunities for growth and innovation.

The 1970s were the golden age of the black gold. After Dubai discovered oil in 1966, it based its economic growth on this resource and developed at a greater speed than any Western country. However, Dubai's leaders recognized early on that reliance on oil was not sustainable in the long term and anticipated a transition. During the 1970s oil crisis, when asked about the drop of oil prices, the late UAE Prime minister Sheik Said declared:

“It’s a challenge and not a crisis.”

In fact, by the 1990s, oil revenue accounted for 25% of Dubai's GDP, a figure that has dramatically decreased to about 1% today (Ajaj et al., 2019). The realization that economic diversification was crucial for sustainable growth led Dubai to pivot towards sectors like technology, tourism, finance, and trade instead, positioning itself as a regional hub for more than 100 international financial firms.

Dubai’s shift was not just about diversification. It also included reflections around sustainability and broader strategic planning within a long-term outlook: the establishment of the Green Building Council in 2006, the very year that the UAE recorded the highest carbon footprint globally, marked a significant step towards integrating environmental sustainability into the national agenda (Ajaj et al., 2019). This was further evidenced by the 2010 Dubai municipality's Green Building Regulations and Specifications decree requiring all new constructions to adhere to strict sustainability norms to reduce their ecological footprint. Although the implementation has faced challenges due to financial constraints, this initiative is a testament to the UAE’s comprehensive approach to sustainability as it covers a wide array of sustainability aspects, including energy and water efficiency, renewable energy use, waste reduction, and the promotion of healthier habitat environments (e.g., the decree requires that 50% of the materials used in construction be sourced from environmentally friendly options). The same year, the Abu Dhabi Urban Planning Council introduced the Estidama program, which includes its sustainability label, as part of a broader commitment to sustainable development (“estidama”, translates into “sustainability” in Arabic). Similarly, the Estidama label encompasses the Pearl Rating System, which is applied to buildings, villas, and communities to ensure they meet certain sustainability standards related to energy use, water conservation, waste reduction, and improved environmental quality. The program is designed to guide the development of sustainable buildings and communities within the Emirate of Abu Dhabi and is integral to the Vision 2030 plan for a more sustainable Abu Dhabi.

More recently, ambitious initiatives have included the development from 2013 of the Sustainable City projects, and the UAE's hosting of COP28 in 2023, showcasing the broadening of the scope of its approach to environmental sustainability, from local shift to global leadership in environmental sustainability efforts. Another such dynamic at play is the growing financial support to the GCC sustainability entrepreneurship scene: Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea Farms, specializing in saltwater-based agriculture solutions, raised $16 million in funding in August 2021. Similarly, the Abu Dhabi Investment Office (ADIO) allocated $141 million in 2020 to agriculture companies, including Pure Harvest and AeroFarms, to bolster the emirate's AgriTech sector. These investments signal strong support for innovative agriculture within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region.

Visit to the “The Sustainable City”

Initiated in 2013 and completed in 2018, the Sustainable City is a 46-hectare community designed to be net zero energy. It was developed by Diamond Developers, whose CEO, Faris Saeed, drew inspiration from the University of California Davis's West Village.

The Sustainable City incorporates green spaces, energy-efficient buildings, and a range of sustainable technologies to minimize its carbon footprint. The city also utilizes solar energy on parking and home rooftops to meet its energy needs, recycles all its water and waste, uses energy-efficient buildings with UV-reflective paint, integrates a wastewater recycling system that separates grey and black water using papyrus as a biofilter for waste reduction, and supports urban agriculture, thereby serving as a model for sustainable urban development. The Sustainable City fosters a car-free and active lifestyle with shaded streets, green spaces, cycling lanes, jogging paths, and an equestrian center. It also seeks to inscribe itself in the UAE’s cultural and historical landscape as it is characterized by residential areas reminiscent of Dubai's historical Bastakiya district.

This dual strategy of economic growth and local ecological sustainability innovations for global sustainability stewardship projection is perhaps most vividly portrayed in the plans surrounding Dubai Expo 2020: the creation of a new city for the Expo, designed to be smart and sustainable, highlights the Emirati leadership's vision of intertwining sustainability with economic development. Similarly, Masdar City, with its aim to be the “world’s most sustainable eco-city”, represents an ambitious endeavor to harmonize technological innovation with environmental stewardship, aiming for a substantial return on investment through the development and exportation of clean technologies (The Masdar Initiative, 2015).

Hence, these developments also align with Dubai's marketing strategy to position itself as a world city at the forefront of new adaptation initiatives: by viewing environmental challenges not as barriers but as opportunities for growth and development, the UAE, especially Dubai, has positioned itself as a leader in sustainable development.

Lessons for Entrepreneurship: Leveraging Constraints as a Motor for Innovation

Dubai's journey from an oil-dependent economy to a global innovation hub can be seen as a case study of constraint-driven innovation: recognizing the finite nature of oil reserves, Dubai was prompted to to explore and invest in new sectors, diversification away from oil, and its emergence as a global innovation hub.

The interplay between constraints and innovation has been explored in various theoretical frameworks and is now established as a cornerstone of modern business theory and practice. Mckinsey (2019) highlights the notion of "disciplined innovation," where constraints are not seen as barriers but as frameworks within which creativity and innovation can flourish. This view of innovation highlights the need for a balance between too much and too little constraint; while the absence of guidelines can lead to chaos and inefficiency, the right amount of limitation can foster focused creativity and coordinated effort.

Similarly, a 2018 Harvard University literature review study synthesized findings from 145 studies to conclude that constraints could indeed help catalyze creativity and innovation. This study underscored that constraints, whether in the form of limited resources or stringent guidelines, compel individuals and organizations to think more critically and creatively (Haught-Tromp, 2018).

In fact, while this may not necessarily seem evident at first glance, this concept finds resonances in a wide-range of areas, from management to art:

First, in management: in 1984, Dr. Eliyahu Moshe Goldratt introduced the Theory of Constraints (TOC) in his book, highlighting how every system's performance is dictated by some key constraints. Goldratt's insights revealed that acknowledging and addressing these constraints could lead to significant improvements in efficiency and productivity, a principle that holds true across industries and scales, from individual enterprises to entire nations (Goldratt, 1984).

In business strategy and company culture, it has also been noted that by recognizing and strategically navigating limitations, organizations can foster a culture of innovation, efficiency, and adaptability. The case of Amazon — which has consistently pioneered disruptive technologies in areas like e-commerce or cloud computing — can be cited. For instance, one of Amazon's Leadership Principles affirms that “constraints breed resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention.” This ethos is mirrored in various facets of the company's operations, from its frugal use of resources to artits innovative product development and market strategy approaches, but also in a seemingly more prosaic practice: the “two pizza rule,” a principle designed to enhance productivity and foster creativity by limiting meeting sizes to what two pizzas can feed. This guideline isn't just about meeting size; it's a reflection of Amazon's commitment to maintaining agility, fostering direct communication, and encouraging decision-making within smaller, more focused groups.

In economic theory, Joseph Schumpeter's concept of “creative destruction” parallels the idea that constraints and challenges can drive progress and innovation. Schumpeter's theory suggests that economic evolution occurs through the dismantling of old paradigms and the emergence of new, more efficient practices and structures. Again, this process is inherently linked to entrepreneurial activity, where recognizing and navigating constraints leads to groundbreaking innovations and market transformations.

Next, in artistic creation: many artists have also demonstrated and explored how self-imposed constraints can guide and nurture unique creative outputs. For instance, Austin Kleon embraces the constraints of copyright law's fair use doctrine to craft a unique collection of poems. In “Newspaper Blackout,” he selectively redacts text from newspapers using a permanent marker to transform ordinary press articles into visual and literary manifestations of constrained creation. We can also find a parallel in Georges Perec’s novel “A Void” (“La Disparition”) written entirely without the letter “e”, the most commonly used letter in the French language. Another example is the work of Sol LeWitt, who created a series of wall drawings and structures based on a set of guidelines or constraints that he defined, but which were then executed by others. Similarly, Igor Stravinsky is known to have articulated that “the more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one's self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution.”

Lastly, in entrepreneurship, Pure Harvest provides an example of value creation by leveraging controlled environment agriculture technology to defy the UAE’s harsh desert climate and contribute to regional food security. Its innovative approach not only addresses local challenges of water scarcity and food production but also offers scalable solutions that could mitigate global climate change impacts.

Visit to the smart farm startup “Pure Harvest”

Growing tomatoes in the desert, Pure Harvest exemplifies the UAE innovation under constraint spirit.

Founded in 2016 and having secured $64.5 million in convertible funding by 2020, the startup utilizes controlled environment agriculture technology to produce high-quality, fresh produce in the arid UAE climate. It operates three farms in the UAE and is expanding into Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Pure Harvest's success highlights the potential of technology to overcome environmental constraints and contribute to food security in the region (Kurtz, 2020).

In this stead, the emergence of other UAE-based AgriTech startups like Mayasim Agricultural Marketing LLC, World of Farming, Below Farm, and Madar Farms further exemplifies the UAE’s movement towards leveraging leveraging its strategic position in the MENA region to address some of the most pressing global challenges in agriculture and food security through innovation and ecological stewardship:

- Mayasim Agricultural Marketing LLC, develops cutting-edge AgriTech solutions for enhanced productivity and minimum resource use.

- World of Farming is a startup that provides fresh, cost-effective, and sustainable animal feed, addressing the critical challenge of sustainable feed production in arid environments and helping reduce the environmental footprint of livestock farming. World Farming owns the world’s largest indoor farm in Dubai.

- Below Farm has pioneered growing mushrooms in the desert using circular farming techniques, demonstrating the potential of non-traditional agriculture in arid climates while minimizing waste and maximizing resource efficiency.

- Madar Farms proposes scalable plug-and-play vertical farming platform solutions to reduce land, water and energy use. It also expands the Sustainable Future programme aimed at educating the public on sustainability practices and fostering habit change towards more sustainable living in the UAE.

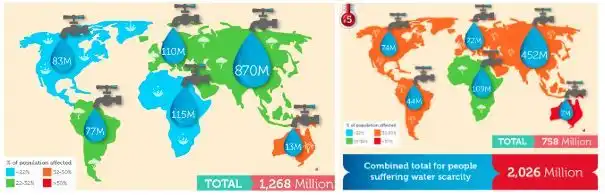

The looming consequences of climate change underscore the urgency of such innovations since the water and food security challenges that the UAE and the GCC countries sought to tackle due to their specific environment are generalizing to many other areas of the world: the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research highlights that global warming will affect the whole world's water supplies in the century ahead leading hundreds of millions of people to experience new or aggravated forms of water scarcity by 2100, even with “just” two degrees Celsius of warming (i.e., the international target since the COP15 Paris Agreement). The estimates of additional population facing water resource stress ranges from 485 million people with 2°C, to 1.2 billion people with 5°C, with Asia, Africa, and Latin America as the most affected regions. According to the World Water Development (UN) report, 50% of the world population will be under high water scarcity by 2050 (Gupta et al., 2016).

On the other hand, a report released by the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World in July 2020 notes that almost 690 million people were hungry in 2019, a number projected to rise by nearly 60 million within five years. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these figures, with over 130 million additional people projected to be facing chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

In fact, the UAE's AgriTech scene is part of a broader global movement towards sustainable agriculture and food security. For instance, Plenty, a US-based indoor vertical farming company, secured $140 million in funding from SoftBank in 2020, underscoring the growing investor interest in such sustainable farming solutions.

Hence, the burgeoning AgriTech entrepreneurship in the UAE and beyond represents a crucial step towards addressing global food and water security challenges. Moreover, by harnessing the UAE’s environmental challenges as starting points for solutions, startups like Pure Harvest also show that constraints should not always be seen as barriers but also as frameworks within which creativity and innovation can flourish.

Bibliography

Acar, O. A. (2019, November 22). Why constraints are good for Innovation. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/11/why-constraints-are-good-for-innovation

Alderman, L. (2010, October 27). Dubai faces environmental problems after growth. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/28/business/energy-environment/28dubai.html

Ali, B. M., Manikas, I., & Sundarakani, B. (2022). Food security in the United Arab Emirates: External Cereal Supply Risks. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2149491

Arabian Business. (2022, September 13). Sheikh Mohammed tours Dubai's largest $40 million vertical hydroponic farm. Arabian Business. Retrieved from https://www.arabianbusiness.com/culture-society/sheikh-mohammed-tours-dubais-largest-40-million-vertical-hydroponic-farm

Central Intelligence Agency. (2024). Dubai - CIA World Factbook Page. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/united-arab-emirates/

Charles, M. (2023, March 23). Power in your problems: How constraints inspire creativity & drive innovation. Medium. https://mauracharles.medium.com/power-in-your-problems-how-constraints-power-creativity-drive-innovation-ba1483f603d6

DeMilked. (n.d.). The evolution of iconic cities before and after. Retrieved from https://www.demilked.com/iconic-cities-evolution-before-after/

Dubai remains world’s Busiest International Airport. Emirates247. (2017, January 24). https://www.emirates247.com/business/dubai-remains-world-s-busiest-international-airport-2017-01-24-1.646965

Duncan, G. (2022, August). What causes the UAE’s sandstorms and are they dangerous? The National. https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/2022/08/15/what-causes-the-uaes-sandstorms-and-are-they-dangerous/

The Economist Newspaper. (2024). Dubai - Global Food Security Index. GFSI. https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/

Fleck, A. (2023, August 7). The world’s ten busiest airports. Statista. https://www.statista.com/chart/19007/busiest-airports-by-passenger-traffic/

Grace, S. (2022, February 17). How constraints stimulate innovation. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-constraints-stimulate-creativity-sean-grace

Holodny, E. (2016, December 22). 155 years of oil prices - in one chart. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/155-years-of-oil-prices-in-one-chart

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2023). Country analysis executive summary: United Arab Emirates. Retrieved from https://www.eia.gov/international/content/analysis/countries_long/United_Arab_Emirates/

Salem, S. B., & Jagadeesan, P. (2022). Food supply chain in pandemic, geopolitical, and climate change era - efforts of United Arab Emirates (UAE). agriRxiv, 2022. https://doi.org/10.31220/agrirxiv.2022.00142

Schaar, J. (2019). A CONFLUENCE OF CRISES: ON WATER, CLIMATE AND SECURITY IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA. SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security, 2019(4), 1–20.

Sull, D. (2015, May 1). The simple rules of Disciplined Innovation. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-simple-rules-of-disciplined-innovation

WAM. (2005). UAE water consumption one of the highest in the world. وكالة أنباء الإمارات. https://wam.ae/ar/details/1395227467673

Visit the Learning Expedition page to find out more about the program.

Cover image caption: Students at Pure Harvest office with Lucio Baron, Director of the strategy (credits: Yasmina Abou-Haka)

Contact us

Any questions? Contact us at centre.entrepreneuriat@sciencespo.fr.