Home>Who will lead the way in the Middle East? Russia, Iran, or Turkey? Interview with Bayram Balci and Nicolas Monceau

13.10.2021

Who will lead the way in the Middle East? Russia, Iran, or Turkey? Interview with Bayram Balci and Nicolas Monceau

In a recently published volume in the Sciences Po Series in International Relations and Political Economy with Palgrave Macmillan, Bayram Balci and Nicolas Monceau bring together ten contributors to explore the complexity of the Syrian question and its effects on the foreign policies of Russia, Iran, and Turkey. This collection focuses on the effects of the Syrian crisis in terms of its initiating new forms of governance by the Russian, Iranian, and Turkish regimes. Many articles and a number of books have been written on this conflict, which has lasted over ten years, but no publication has examined simultaneously and comparatively how these three states are participating in the shared management of the Syrian conflict. The following is an interview with the two editors of the volume, Bayram Balci and Nicolas Monceau.

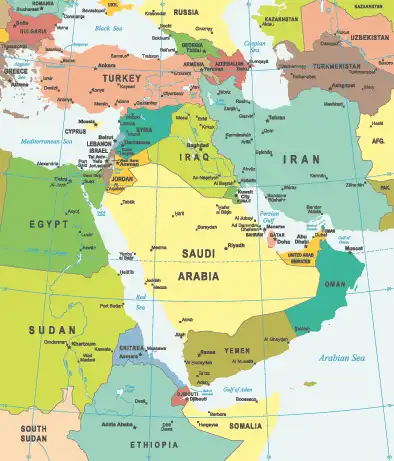

Syria is the scene of an international conflict that impacts on Middle Eastern politics and more broadly for the so-called international order. Can you remind us who are the main actors involved in this long-lasting conflict—local, regional, and international ?

The Syrian crisis has been going on for more than ten years now, and involves various local, regional, and even international actors. To understand the multiplicity of these actors, and the various links between them, we need to go back to the initial dynamics of the crisis—also referred to as a war or conflict. The origins of the crisis lie in the context of the "Arab Spring" (starting in Tunisia in December 2010), during which a popular protest movement emerged in Syria—as it did in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya—to call for democratic reforms from the Ba'ath party, which had been in power for several decades. The brutal response of the government, through the scale of the repressive force it used against the originally peaceful demonstrations, led to a militarisation of the opposition, which then fractured into several trends over time.

- On one side is the Syrian regime and its traditional supporters whom we have already mentioned (Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah). To this list we could also add a fringe of the Kurdish national movement represented by the PYD and its military branch, the YPG—both of which emanate from the PKK coming from Turkey, which occupies a large territory in Syria and remains in an ambiguous relation with Damascus.

- Confronting this is the Syrian opposition—the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and the jihadist organisations that split into multiple groups. Among the latter is ISIS, which conquered many territories in Syria beginning in the mid-2010s but was eventually militarily defeated by a coalition of regional and international forces.

- As for the other actors who were initially against the regime, such as the Gulf States, their position toward the conflict has evolved. They have gradually distanced themselves from the Syrian opposition and are moving toward a tacit accommodation of the regime of Bashar al-Assad. Similarly, the United States and the EU remain minor players, with a policy that prioritises the non-recurrence of the threat of the Islamic State.

- Finally, a major player in this conflict is Turkey, which, while remaining very hostile to Bashar al-Assad, adopts a Syrian policy focused on a single objective: to avoid the establishment in northern Syria of a rear base for the PKK, which could intensify its guerrilla warfare against the Ankara authorities from there. Turkey also intends to prevent the emergence of an autonomous Kurdish entity in Syria that could revive separatist claims in Turkey.

The present volume focuses on the impact of this conflict on three powers—Turkey, Russia, and Iran—and on their role in the Syrian war. Are these three actors equally involved in the conflict?

As we seek to show in this recently published collective work, Turkey, Russia, and Iran have become the three major players in the Syrian conflict, at both the military and the political level, through the Astana process,(1) but they do not necessarily share the same interests and influence in the region or on the main local players: As Mitat Çelikpala shows in his chapter, Russia supports Bashar al-Assad's regime militarily and politically. Its military intervention from 2015 onwards has saved the Syrian regime and kept Bashar al-Assad in power. Russia will surely play an important role in the reconstruction of Syria after the end of the conflict. Turkey, which had engaged in a dramatic rapprochement with Bashar al-Assad's regime before the crisis began in 2011, has since strongly opposed the Syrian regime by calling for Bashar al-Assad's departure. Bayram Balci’s and Thomas Pierret’s contributions to our volume show us that Turkey has provided military and political support to the Syrian opposition in all its diversity, including, it seems, to jihadist organisations. Iran, for many strategic and even confessional reasons, like Russia, supports Bashar al-Assad's regime, financially, politically, and militarily (by sending fighters), as Bayram Sinkaya shows in his chapter on this issue. As far as the Western powers are concerned, the European Union, whose influence in the Middle East has been declining for several decades, is absent. On the other hand, as Joseph Bahout examines in his chapter, while initially a major player in the Syrian conflict, the United States has withdrawn since the military defeat of the Islamic State.

However, the United States remains an important supporter of the Syrian Democratic Forces whose backbone is the PKK-linked PYD. As such, the United States remains a significant power in Syria, and may play a role in the future Syria, whose reconstruction is far from having begun, as the work in this volume by Igor Delanoe shows. Moreover, the US support given to Kurdish organisations in northern Syria has contributed to a sharp deterioration in relations between the United States and Turkey, its historical ally and a major regional actor, following several already existing tensions, as Ömer Taşpınar shows in his contribution.

Has the conflict changed the relationship between the three countries?

The continuation of the conflict has indeed changed the relationship between the three powers, especially with regard to bilateral relations between Turkey and Russia, as Nicolas Monceau demonstrates in his chapter.

In the early stages of the Syrian crisis, Russia and Turkey supported two opposing sides: the Syrian regime for the former and the opposition for the latter. The conflict in Syria even led to a major diplomatic crisis between the two countries in 2015, when Turkey shot down a Russian bomber crossing its airspace toward Syria. Despite initially antagonistic positions and diverging interests, Turkey (whose relations with its traditional Western allies have been deteriorating over years for various reasons) and Russia are nevertheless coming closer together through their participation in the Astana process with Iran to seek a political solution to the Syrian conflict. The aim of this triumvirate is to lead the regional actors to resolve the problem without involving the Western powers. Relative military cooperation is also taking place on the ground, but this does not prevent temporary confrontations and crises from arising, as occurred in the Idlib region in February-March 2020, when the Syrian regime with Russia’s tacit support, or the Russian forces themselves, killed 33 Turkish soldiers in Idlib.

Turkey and Iran have also supported opposing sides during the conflict in Syria; however, they have done so without jeopardising bilateral relations between the two countries in other spheres (notably economic and commercial ones).

Finally, while they share close perspectives on the conflict in Syria, Russia and Iran do at times have disagreements, as Clément Therme explains in his chapter. For example, Russia does not much appreciate how Tehran approaches the Syrian issue in order to better implement its anti-Israeli policy.

You mention that there is “collaboration in divergence”. Would you mind explaining this concept a little and giving some examples?

“Collaboration in divergence” is a term used to describe the relationship that has existed between Turkey and Russia since the outbreak of the conflict in Syria. As Nicolas Monceau explains in his contribution, these two powers have been cooperating to conduct peace negotiations in Syria within the framework of the Astana process, launched in 2017, of which they, together with Iran, are the guarantors. Political, commercial, and energy cooperation between the two countries has also deepened considerably over the past decades under the impetus of leaders Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. At the same time, Turkey and Russia have multiple disagreements in the field of foreign policy, in particular regarding the recent regional conflicts in Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh, where they supported opposing sides.

Discussions about a “new regional order” are legion. What is different in this context?

For decades, even centuries, Western powers have played a major role in the Middle East as dominant actors. The fall of the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century led to a stronger influence of European powers in the region. After the Second World War, the Cold War contributed to the strengthening of the role of the world powers—the US and the USSR—in the Middle East in the context of bipolarisation. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has intervened on several occasions to change the regional order, in particular with the Gulf War in 1990-1991 and the military intervention of the Western coalition in Iraq in 2003, which led to the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime.

In the specific context of the Syrian conflict, the dynamics observed over the last ten years highlight strong developments that could herald the establishment of a new regional order in the future, a transition that is well explained by Bertrand Badie in his chapter published in this volume. These ongoing developments reflect a shift in the balance of power marked by the weakening of the traditional influence of the Western powers (the United States and, to a lesser extent, the European powers, especially France and the United Kingdom) who were the major actors in the making of the new states in the region after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the growing assertion of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. The reduced influence of the United States in this region following the withdrawal of American forces (from Iraq and Syria, and more recently from Afghanistan, completed in August 2021), which is indicative of American policy, and the absence of the European Union are thus combined with the growing power and influence of the more authoritarian regimes present in the region, namely Turkey, Russia, and Iran. Some observers believe that the Astana process initiated for Syria could indeed serve as a “model” for the resolution of other regional conflicts, primarily the conflicts in Libya or Karabakh.

Discover the Sciences Po Series in International Relations and Political Economy

JOIN OUR CONFERENCE ON 6 DECEMBER (REGISTER HERE)

Interview by Miriam Périer, CERI.

All pictures copyright: Shutterstock

Notes

- 1.The Astana process refers to a series of multi-party meetings between different protagonists in the Syrian conflict. The culmination of this process, the so-called Astana Agreement, is a treaty signed on 4 May 2017 by Russia, Iran, and Turkey on the creation of four ceasefire zones in the country. In practice, this agreement makes these three states the main operators or stabilisation forces in a conflict that is awaiting a final solution that is slow in coming. On the Astana process, see: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/30/syrian-war-all-you-need-to-know-about-the-astana-talks.

Follow us

Contact us

Media Contact

Coralie Meyer

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 85

coralie.meyer@sciencespo.fr

Corinne Deloy

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 68

corinne.deloy@sciencespo.fr