Home>Introduction: Revisiting the State, Again

27.10.2021

Introduction: Revisiting the State, Again

By Eberhard Kienle

Ten years after large scale protests in numerous Arab countries drove home the importance of collective action, contestation, social movements, and other forms of politics from below, political actors and observers alike have once again shifted their attention toward the state—or what they consider as such. Even though it emphasises the state’s deficiencies or even absence, the—contested—concept of the “failing state” and its avatars refer to an entity called the state. The reaffirmation of authoritarian rule in such countries as Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, and more recently even Tunisia, ambitious “development” plans like Vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia and their attendant public policies, and the nuclear programme in Iran all illustrate the importance and impact of states, however conceived, defined, delineated, and composed. Continued military action or threats, as well as action to combat—or deny—the coronavirus pandemic, only confirm this observation.

The attraction that the state continues to exert on political actors and indeed movements appeared patently in the short-lived Islamic State, which, like other states, began as an “irregular” armed group ramifying first into a social movement, then into fledgling institutions. No doubt, in political and academic debates, the fortunes of the state have repeatedly changed throughout the past, not only with regard to the MENA area but also with regard to developments worldwide. Without claiming to open another round of attempts at Bringing the State Back In (Evans et al. 1985) , the present issue of the Dossier du CERI seeks to re-examine this—moving—object that already more than three decades ago was described as “Alien and Besieged Yet Here to Stay” (Korany 1987). As a matter of course, analysing the transformations of the state cannot be separated from examining its relations with society, which has frequently, but not always convincingly, been conceived of as its opposite.

With reference to both current and earlier debates dedicated to the characteristics (but not ipso facto specificities or even the ontological difference) of states in the MENA area, the contributors gathered here focus on features that have come to mark the political regimes of these states as well as their economic and social regimes. These features include “authoritarian upgrading” in some cases, the companion process of authoritarian “downgrading” in other cases, and the disintegration of states as a third process that has frequently been seen as “state failure”. In many instances, these features include a continued emphasis on welfare policies of various sorts. These policies have no doubt been affected, modified, and eroded but not terminated by worldwide “neoliberal” dynamics. In fact far from it; distributive policies have been used to rein in and pre-empt protests both in and after 2011. Reforms of social and labour policies are also under way in several countries, including Egypt and the Gulf monarchies, which are transforming but at the same time maintaining distributive “social pacts”. Even in disintegrating states, actors who participate in activities of “competitive state building” pursue social policies, demonstrating that welfare is perceived as an essential component of “modern” statehood. In actual fact, the disintegration of states like Iraq seems to be closely linked to their incapacity to provide social services and public goods in situations of stress caused by external military intervention, economic decline, and economic reforms that aim at macroeconomic stabilisation rather than inclusive growth and distribution. In Lebanon, for example, some activists in the current protests express nostalgia for the Shehabist period during which limited attempts were made to redistribute wealth: above and beyond corruption, it is thus the model of a state tailored to certain conceptions of economic liberalism that protestors denounce.

Building on two virtual meetings convened by Laurence Louër and Eberhard Kienle at CERI in 2020 and 2021, this Dossier seeks to analyse the transformation of MENA states in light of global processes and their impacts, be it in terms of adaptation or resistance. Without neglecting other empirically based attempts at explanation, the contributions pay particular attention to dynamics that have been unfolding since the end of the Cold War and the onset of the current phase of globalisation in the early 1990s.

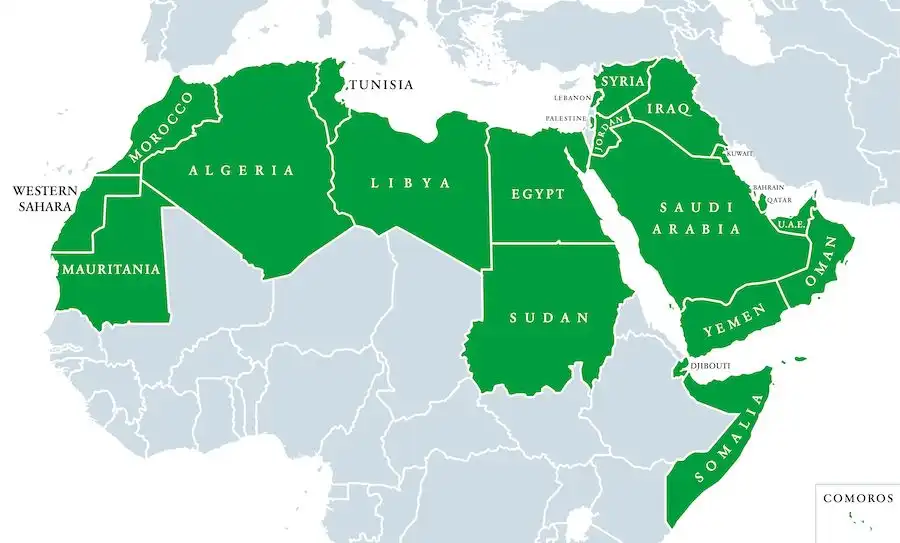

Map of the MENA region states. Copyright: Shutterstock

Contributions

The first four papers published in this Dossier focus on processes, recent as well as long-term, each of which marks a considerable number of entities defining themselves as states or defined as such by others.

Opening the Dossier, Ariel Ahram in his contribution “Fluid and Failing, Yet Static: The Afterlife of Arab States” emphasises the growing diversity and plasticity of such entities in terms of institutions and performance, which ultimately question familiar definitions of statehood and stateness (if distinguished from statehood).

For his part, Hamit Bozarslan in his contribution "From Leviathan to Behemoth: The State in the Arab World of the 2010s" shows beneath the current disintegration of some—but by no means all—states the collapse of "cartels that recall the "drug cartels" elsewhere. Having managed to dominate these states over decades, these cartels finally failed to resist global and internal pressure.

Subsequently, Raymond Hinnebusch in his “Statehood in the Middle East and North Africa: Approaches from Historical Sociology, Part I, the Rationale” argues that historical sociology inspired by Weber, which is sensitive to the conditions under which states (were) formed and survived, remains the best bet to grasp and explain such diversity, taking issue with claims that the approach is normative and Eurocentric.

The relevance of history is vividly illustrated by Guillaume Beaud who, in “Dealing with the State: Politicisation of State Bureaucracies and Differential State Capacity in Post-revolutionary Iran and Postcolonial Pakistan”, provides a vivid illustration of long-term processes that have shaped, at times counterintuitively, the institutional capacities and performance of bureaucracies seen as an important element of statehood.

Far from ignoring the processes that have led to the large scale disintegration of a number of states, in my own contribution to this Dossier I ask why they have not entirely disappeared from the maps. In "Why Have 'Failed States' Failed to Disappear", I argue that their however residual survival rests at least partly on the impact that even shaky institutions continue to have on peoples' acts and minds.

Comparing two crucial periods for the political economy of the region, Ishac Diwan, in “How Economic Policies Affect Political Regimes? Comparing the 2010s to the 1980s in the Middle East and North Africa”, examines the impact of economic policies on political regimes faced with a fiscal and debt crisis, in both periods, although under different global conditions. He shows that the political consequences of the new crisis may be far from uniform and affect states in divergent ways.

Building on his initial contribution, Raymond Hinnebusch in Statehood in the Middle East and North Africa: Approaches from Historical Political Sociology, Part II turns to the difficult question of Conceptualizing and Measuring the features which may be seen to constitute and define statehood and thus in the broader sense states themselves.

References

Evans, Peter, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Theda Skocpol, eds. 1985. Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Korany, Bahgat. 1987. “Alien and Besieged Yet Here to Stay: The Contradictions of the Arab Territorial State”. In The Foundations of the Arab State, edited by Ghassan Salame, 44-75. London: Croom Helm.

Eberhard Kienle is Research Professor at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) with an appointment at CERI and teaches politics at Sciences Po Paris. He previously served as director of the Institut français du Proche-Orient (Ifpo, French Near East Institute) in Beirut, member of the UN OHCHR Fact Finding Mission to Syria, and Programme Officer at the Ford Foundation Cairo office. Publications include Ba’th versus Ba’th: The conflict between Syria and Iraq, 1968-1989 (I.B. Tauris, 1990) and A Grand Delusion: Democracy and Economic Reform in Egypt (I.B. Tauris, 2001); The Arab Uprisings: Transforming and Challenging State Power co-edited with Nadine Sika (I.B.Tauris, 2015).

Cover image: The city of Oman, Algeria. ©Photo by Muath Beragdar for Shutterstock

(credits: Muath Beragdar for Shutterstock)

Follow us

Contact us

Media Contact

Coralie Meyer

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 85

coralie.meyer@sciencespo.fr

Corinne Deloy

Phone : +33 (0)1 58 71 70 68

corinne.deloy@sciencespo.fr