European Union

I.Timeline and Main Documents

After having been reluctant to take over the frame of the “Indo-Pacific”[1]Felix Heiduk and Gudrun Wacker, “From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific: Significance, Implementation and Challenges,” SWP Research Paper (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, July 2020), 35, … Continue reading for the last years, the European Union (EU) adopted the concept early this year and released an official strategy this September. The EU largely avoided the conflict-laden term in the last years to avoid aligning itself with the regional approach of the US and thereby alienating China. For example, its 2016 Global Strategy mentioned the word “Indo Pacific” only once,[2]European Union, “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe: A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy,” June 2016, 38, … Continue reading in regard to promoting human rights and democratic transitions in Myanmar”. Instead, it followed an Asia-Pacific frame and pursued individual strategies with partner countries in the region (namely China[3]Council of the European Union, European Commission, and People’s Republic of China, “EU-China Summit Joint Statement” (Brussels, Belgium, April 9, 2019), … Continue reading, India[4]European Commission and Council of the European Union, “Elements for an EU Strategy on India” (Brussels, Belgium, November 20, 2018)[5]EU/India, “Joint Statement – 15th EU-India Summit, 15 July 2020,” July 15, 2020, … Continue reading, Japan[6]The European Union and Japan, “Strategic Partnership Agreement,” August 24, 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22018A0824(01)&from=EN. and Korea[7]Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Korea, “EU-Republic of Korea Strategic Partnership,” EEAS Homepage, June 30, 2020, … Continue reading), focused on its partnership with ASEAN,[8]“EU ASEAN STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP: Factsheet,” accessed October 21, 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fact-sheet-eu-asean-strategic-partnership.pdf. or pursued a subject- specific strategy on Euro-Asian Connectivity[9]European Commission and Council of the European Union, “JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE, THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS AND THE … Continue reading.

The first clear sign of the EU’s gradual adoption of the Indo-Pacific as a conceptual basis for its strategy were High Representative Josep Borrell’s remarks during the Council meeting in January, where he signaled the EU’s interest to develop its own approach to the region.[10]Council of the European Union, “OUTCOME OF THE COUNCIL MEETING,” 3784th Council meeting, Foreign Affairs (Brussels, Belgium, January 25, 2021), 6, … Continue reading With such a strategy clearly being a part of the common foreign and security policy, and thus subject to the unanimous decision-making, the main hurdle to begin formulating a common strategy was an according consensus among the EU member states. The plan to create a separate strategy was eventually greenlighted in April, when the Council voiced its consensus “that the EU should reinforce its strategic focus, presence and actions in the Indo-Pacific”.[11]Council of the European Union, “OUTCOME OF THE COUNCIL MEETING.” The European Union then formally published its final Indo-Pacific Strategy in September 2021,[12]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL (Brussels, Belgium, September 16, 2021), … Continue reading an event that was overshadowed by the simultaneous unraveling of events related to AUKUS. The strategy’s aspects pertaining to security and defense will also be influenced by the content of the forthcoming ‘Strategic Compass’, which is scheduled to be adopted during the French Presidency in the first half of 2022.[13]European Parliamentary Research Service, “The European Union’s ‘Strategic Compass’ Process” (Brussels, Belgium: European Parliament), accessed October 21, 2021, … Continue reading

The timing of the EU’s strategy is already a first indicator that its position is based on a consensus between the differing strategic interests within the EU. Faced with some states that already have formulated strategies for the region, and other member states that generally would prefer to keep focusing on other pressing strategic concerns,[14]Frédéric Grare and Manisha Reuter, “Moving Closer: European Views of the Indo-Pacific” (Brussels, Belgium: European Council on Foreign Relations, September 19, 2021), … Continue reading the EU was and will always be forced to strike a balance. Apparently, the scale tipped in favor of a EU separate strategy on the Indo-Pacific in the beginning of this year. The limiting factor of the need for consensus is equally important when assessing the content of the final strategy and EU’s subsequent actions in the region. On the other hand, the political weight of this consensus should not be underestimated as it is based on the approval of all 27 EU Foreign Ministers.

II. Objectives and Geography

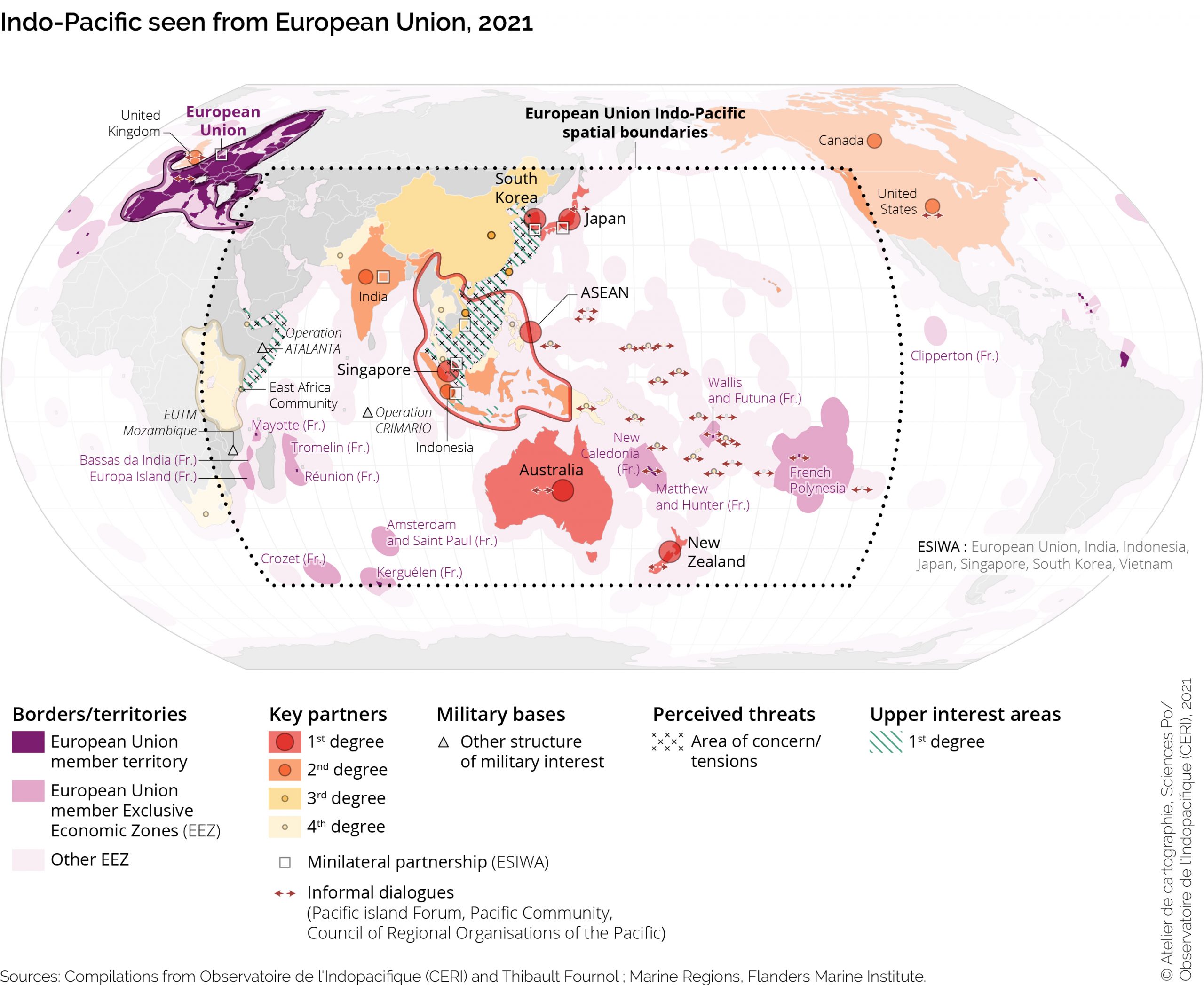

The final EU Strategy defined the Indo-Pacific as the “geographic area from the east coast of Africa to the Pacific Island States”[15]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 1. thereby following the geographic definition of the majority of EU member states.[16]Grare and Reuter, “Moving Closer: European Views of the Indo-Pacific,” 6. The need for a dedicated EU strategy is based on the premise that the Indo-Pacific “increasingly strategically significant for Europe”.[17]Council of the European Union, “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific – Council Conclusions” (Brussels, Belgium, April 16, 2021), 1, … Continue reading The aspects rationale can be subsumed under four reasons:[18]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 1–2.

- the region’s importance for Europe in term of trade and investment

- the region’s significance for global environmental challenges

- increasing geopolitical competition in the region

- the pressure on democratic principles and human rights in the area

The four aspects can also be directly connected to “the seven priority areas”[19]European Commission, 5. in which the EU is aiming to pursue its strategic goals in the Indo-Pacific:

How the seven “priority areas” mentioned in the EU Strategy relate to the four reasons (own graphic)

The EU’s Indo-Pacific approach therefore reflects largely its primarily economic motives and policy-competences, with environmental, normative, and geopolitical factors being other significant aspects. Furthermore, the EU traditionally is neither a security actor nor does it have the capabilities to become one in the Indo-Pacific (let alone the internal consensus to do so). Thus, in the context of the EU the concept of an Indo-Pacific Strategy, as well as any strategic objectives or strategic partners, should be analyzed through a mainly non-geopolitical lens.

However, the significant geopolitical aspect is undeniably a new and significant feature in the EU’s regional Indo-Pacific policy. The geopolitical developments in the region were also likely the main reason why a separate strategy for the Indo-Pacific was considered to be necessary in the first place. While outlining the need for a separate strategy, the Council-conclusions from April mentioned the already existing relevance of the region for the EU in terms of economic, development and environmental policies, but especially highlighted the “intense geopolitical competition” in the Indo-Pacific.[20]Council of the European Union, “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific – Council Conclusions,” 2. The document then connected the potential negative repercussions on “trade and supply chains” and “technological, political and security areas” directly to the EU’s interests.[21]Council of the European Union, 2.

This argumentation highlights that the common denominator within the EU in terms of the Indo-Pacific’s geopolitical significance is not based on a collective interest in taking sides in the unfolding power-competition, but rather on preventing the negative effects this competition could have on the EU’s economic security. After all, the EU is among the leading trade partners and investors in the region, which is also the second largest destination of EU exports, and dependent on the supply-chains that flow through certain contested sea zones.

III. Means

This wide range of strategic goals and principled motivations are also reflected in the means that the EU has outlined for its engagement in the area. To safeguard its economic security, the EU is able to leverage its wide array of economic tools of concluding more free-trade agreements, diversifying supply-chains, combating unfair trading practices or developing programs with regional actors on digital cooperation or infrastructure connectivity.[22]Garima Mohan, “Assessing the EU’s New Indo-Pacific Strategy,” LSE EUROPPBlog – European Politics and Policy,September 24, 2021, … Continue reading When focusing more on the geopolitical aspect of economic security, the EU’s lack of capabilities and inability to create alliances like state-actors severely limit its available means. Instead, it is left with three groups of security-instruments: cooperation, capacity-building and coordinating its member state’s assets.

Firstly, the EU is pursuing a policy of “Partnership and Cooperation”. Thereby it aims to engage with partners in the region both bi- and multilaterally to “promote effective rules-based multilateralism”. On the bilateral level of cooperation, the concrete policies are:

- Intensify dialogues on counterterrorism, cybersecurity, non-proliferation and disarmament, space and maritime security

- Deploying of additional military advisors to EU Delegations

- Continuing the pilot project of Enhancing Security Cooperation in and with Asia (pilot partners in Indonesia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam)

- Expanding list of existing Framework Participation Agreements for CSDP missions and operations (currently Australia, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand, and Vietnam)

The multilateral effort will be focused on the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus (ADMM+), with additional engagements in the East Asia Summit and the India Ocean Naval Symposium. Other means are the planned establishment of an EU Cyber Diplomacy Network and multilateral initiatives on arms export control and dual use export control.

The second instrument is the strategic contribution to capacity-building initiatives in the region. This includes:

- Expanding the CRIMARIO[23]EU CRIMARIO, “CRIMARIO, Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific,” accessed September 20, 2021, https://www.crimario.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/210920-Crimario-factsheet-EN-final.pdf. Project to Southeast Asia and South Pacific to counter “drug trafficking, human trafficking and wildlife crime, and also illicit financial flows linked to terrorism”[24]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 13–14.

- Encourage better information-sharing mechanisms on maritime security though the regional information fusion centers

- Support for partners on cybersecurity, countering terrorism/extremism developing peacekeeping capacities

- Supplying tools to counter disinformation and interferences

Thirdly, beyond these instruments the EU is forced to rely on the capabilities of its member states. There, it tries to take a coordinating role in the “Team Europe”-approach. Specifically, it aims to:

- Ensure a “meaningful” European naval presence based on Intra-European Coordination (likely through establishing a system similar to the Coordinated Maritime Presences in the Guld of Guinea[25]EEAS, “The EU Launches Its Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept in the Gulf of Guinea” (Brussels, January 25, 2021), … Continue reading[26]Council of the European Union, “Council Conclusions Launching the Pilot Case of the Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept in the Gulf of Guinea” (Brussels, Belgium, January 25, 2021), … Continue reading)

- Continue existing EU naval operations EUNAVFOR Somalia – Operation Atalanta and EUTM Mozambique

- Furthering joint naval activities/exercises, port calls, multilateral exercises between EU member states and regional partners

However, it remains to be seen if and how far the member states with the most capabilities in the region (which also happen to be those with the most ambitious strategies), really let themselves be coordinated by the naturally less-ambitious consensus in Brussels.

I. Partnerships

In General

Within its inclusive and partnership-centric approach on the general level, the EU is largely following its established modus operandi. It pursues a flexible approach to switch among any of the four policy-areas to seek potential for cooperation for a number of regional actors. This pragmatic approach is designed to safeguard the EU’s strategic autonomy without becoming entangled in the evolving power competition. Notably, it does not evaluate the potential for partnership with said actors based on their strategic value in terms of capabilities (for example India). However, offering cooperation to everyone in the region also restricts the depth of strategic cooperation. Following the previous example, the mentioning the naval and development cooperation with Pakistan in its strategy[27]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 13. is not likely to help any rapprochement with Pakistan’s strategically much more valuable eastern neighbor.

Strategic/Like-minded Partners

The key indicator for a hierarchy among the potential partners in the region is the degree of like-mindedness which is attributed in the EU Strategy to Australia, Japan, Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Singapore[28]European Commission, 17. (and implicitly to Japan[29]European Commission, 8.). Furthermore, The EU is clearly emphasizing the “centrality of ASEAN”, which is also the only entity that the EU strategy addresses by name as a “strategic” partner. But this also bases the EU’s strategic approach on an economic union that is arguably even less able to execute a coherent strategy than the EU itself. Meanwhile, the other existing “strategic” partnerships the EU has signed with other regional actors go largely unmentioned in its Indo-Pacific Strategy. The EU also guards a cautious distance from the QUAD as it recognizes the potential for cooperation but limits the “common interest” to “climate change, technology and vaccines”.[30]European Commission, 13.

IV. The China Question

Regarding China, the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy is largely following its traditional approach (partner, competitor, systemic rival), but with notable deviations. The Strategy reiterates the EU’s interest in cooperation with China (the partner-frame). This is supplied by mentioning the China-EU Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) or emphasizing the importance of multilateral fora of which China is a part (Asia-Europe Meeting). The EU also notes “fundamental disagreements” in normative questions with China (systematic rival-frame).

New is the explicit mentioning of China as a factor in “military build-up” in the Indo-Pacific,[31]European Commission, 2. a specification of the geopolitical tensions that was missing in the Council conclusions from April. Furthermore, the EU strategy mentions the potential of the South and East China Sea in the Taiwan Strait to have “a direct impact on European security”.[32]Ibid. This creates a clear linkage between China’s geopolitical advances and EU interests.

The new strategy also reiterates Taiwan’s rank of a “partner” to the EU, although only in issues related to economic, environmental, and technological policy-issues.[33]European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 6, 7, 11. Recently, High Representative Borell even became even more specific by identifying the incursions of Chinese planes into “Taiwan’s air defense identification zone” as having the potential to “have a direct impact on European security and prosperity”.[34]“EU-Taiwan Political Relations and Cooperation: Speech on Behalf of High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the EP Plenary (Delivered by Executive Vice-President for a Europe Fit for a … Continue reading Shortly afterwards, the EU Parliament emphasized the need for closer relations to Taiwan,[35]European Parliament, “EU-Taiwan Relations: MEPs Push for Stronger Partnership” (Brussels, Belgium: European Parliament, October 21, 2021), … Continue reading a vital player in the EU’s semiconductor supply-chains.[36]Jorge Liboreiro, “Von Der Leyen Pitches European Chips Act in a Bid to Boost the EU’s Tech Self-Reliance,” September 28, 2021, … Continue reading How the EU reconciles these new developments with its established threefold-approach to China, its official one-China policy,[37]Council of the European Union, European Commission, and People’s Republic of China, “EU-China Summit Joint Statement,” 1. and its interest not to become entangled in regional coalitions will be a key question for its developing strategic position in the Indo-Pacific.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Felix Heiduk and Gudrun Wacker, “From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific: Significance, Implementation and Challenges,” SWP Research Paper (Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, July 2020), 35, https://www.swp-berlin.org/publications/products/research_papers/2020RP09_IndoPacific.pdf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | European Union, “Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe: A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy,” June 2016, 38, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf. |

| ↑3 | Council of the European Union, European Commission, and People’s Republic of China, “EU-China Summit Joint Statement” (Brussels, Belgium, April 9, 2019), https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/39020/euchina-joint-statement-9april2019.pdf. |

| ↑4 | European Commission and Council of the European Union, “Elements for an EU Strategy on India” (Brussels, Belgium, November 20, 2018) |

| ↑5 | EU/India, “Joint Statement – 15th EU-India Summit, 15 July 2020,” July 15, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/07/15/joint-statement-15th-eu-india-summit-15-july-2020/. |

| ↑6 | The European Union and Japan, “Strategic Partnership Agreement,” August 24, 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22018A0824(01)&from=EN. |

| ↑7 | Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Korea, “EU-Republic of Korea Strategic Partnership,” EEAS Homepage, June 30, 2020, https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/south-korea_en/81748/EU-Republic%20of%20Korea%20Strategic%20Partnership#:~:text=EU-Republic%20of%20Korea%20Strategic%20Partnership%20The%20European%20Union,agreements%2C%20covering%3A%20%E2%80%A2%20political%20relations%20and%20sectoral%20cooperation%3B. |

| ↑8 | “EU ASEAN STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP: Factsheet,” accessed October 21, 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fact-sheet-eu-asean-strategic-partnership.pdf. |

| ↑9 | European Commission and Council of the European Union, “JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE, THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS AND THE EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK: Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy” (Brussels, Belgium, September 19, 2018),https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_-_connecting_europe_and_asia_-_building_blocks_for_an_eu_strategy_2018-09-19.pdf. |

| ↑10 | Council of the European Union, “OUTCOME OF THE COUNCIL MEETING,” 3784th Council meeting, Foreign Affairs (Brussels, Belgium, January 25, 2021), 6, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/48061/st05579-en21.pdf. |

| ↑11 | Council of the European Union, “OUTCOME OF THE COUNCIL MEETING.” |

| ↑12 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” JOINT COMMUNICATION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL (Brussels, Belgium, September 16, 2021), https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/jointcommunication_2021_24_1_en.pdf. |

| ↑13 | European Parliamentary Research Service, “The European Union’s ‘Strategic Compass’ Process” (Brussels, Belgium: European Parliament), accessed October 21, 2021, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/EPRS/graphs/EPRS_Strategic_Compass_final.pdf. |

| ↑14 | Frédéric Grare and Manisha Reuter, “Moving Closer: European Views of the Indo-Pacific” (Brussels, Belgium: European Council on Foreign Relations, September 19, 2021), https://ecfr.eu/special/moving-closer-european-views-of-the-indo-pacific/. |

| ↑15 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 1. |

| ↑16 | Grare and Reuter, “Moving Closer: European Views of the Indo-Pacific,” 6. |

| ↑17 | Council of the European Union, “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific – Council Conclusions” (Brussels, Belgium, April 16, 2021), 1, https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7914-2021-INIT/en/pdf. |

| ↑18 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 1–2. |

| ↑19 | European Commission, 5. |

| ↑20 | Council of the European Union, “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific – Council Conclusions,” 2. |

| ↑21 | Council of the European Union, 2. |

| ↑22 | Garima Mohan, “Assessing the EU’s New Indo-Pacific Strategy,” LSE EUROPPBlog – European Politics and Policy,September 24, 2021, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2021/09/24/assessing-the-eus-new-indo-pacific-strategy/. |

| ↑23 | EU CRIMARIO, “CRIMARIO, Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific,” accessed September 20, 2021, https://www.crimario.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/210920-Crimario-factsheet-EN-final.pdf. |

| ↑24 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 13–14. |

| ↑25 | EEAS, “The EU Launches Its Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept in the Gulf of Guinea” (Brussels, January 25, 2021), https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/91970/eu-launches-its-coordinated-maritime-presences-concept-gulf-guinea_el. |

| ↑26 | Council of the European Union, “Council Conclusions Launching the Pilot Case of the Coordinated Maritime Presences Concept in the Gulf of Guinea” (Brussels, Belgium, January 25, 2021), https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/48054/st05387-en21.pdf. |

| ↑27 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 13. |

| ↑28 | European Commission, 17. |

| ↑29 | European Commission, 8. |

| ↑30 | European Commission, 13. |

| ↑31 | European Commission, 2. |

| ↑32 | Ibid. |

| ↑33 | European Commission, “The EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” 6, 7, 11. |

| ↑34 | “EU-Taiwan Political Relations and Cooperation: Speech on Behalf of High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the EP Plenary (Delivered by Executive Vice-President for a Europe Fit for a Digital Age Margarethe Vestager)” (Brussels, Belgium, October 19, 2021), https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/105879/eu-taiwan-political-relations-and-cooperation-speech-behalf-high-representativevice-president_en. |

| ↑35 | European Parliament, “EU-Taiwan Relations: MEPs Push for Stronger Partnership” (Brussels, Belgium: European Parliament, October 21, 2021), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20211014IPR14926/eu-taiwan-relations-meps-push-for-stronger-partnership. |

| ↑36 | Jorge Liboreiro, “Von Der Leyen Pitches European Chips Act in a Bid to Boost the EU’s Tech Self-Reliance,” September 28, 2021, https://www.euronews.com/2021/09/16/von-der-leyen-pitches-european-chips-act-in-a-bid-to-boost-the-eu-s-tech-self-reliance. |

| ↑37 | Council of the European Union, European Commission, and People’s Republic of China, “EU-China Summit Joint Statement,” 1. |