Home>Indo-Pacific Strategies>Australia

Australia

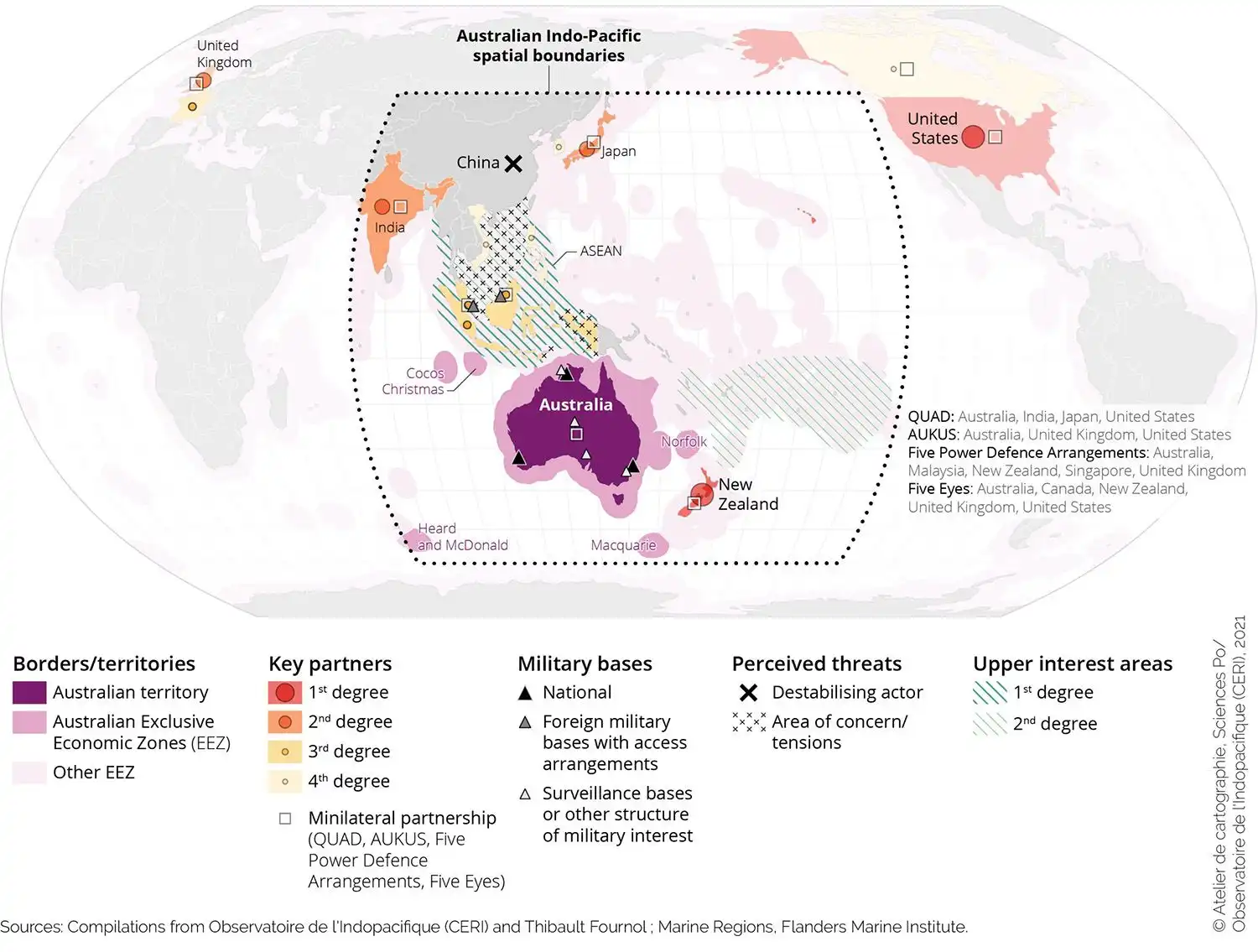

Indo-Pacific seen from Australia 2021

“For the first time a concept provides a definition of our region that automatically includes Australia as a recognized geopolitical partner and actor.”

Rory Medcalf, 19th May 2021(1)

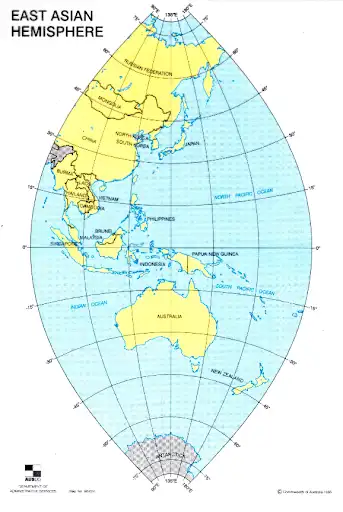

Geography: Australia’s cartographic imagination(2)

For no other country, with the possible exception of Indonesia, does the notion of the Indo-Pacific also serve so strongly as a form of self-description. Indeed, the term entered official discourse in both countries in the same year, 2013, with the then Indonesian Foreign Minister, Dr Marty Natelagawa(3), giving a speech in Washington DC (Natelagawa 2013) on the factors that increasingly bind countries from afield as East Africa to Japan into a complex web of interdependence and mutual interest.

The Australian Government’s 2013 Defence White Paper referred to the Indo-Pacific as THE region in which Australia finds itself. In the following 2016 Defence White Paper and the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (Australian Government 2013, 2016, 2017) the term had become imbedded. By the time of the (Australian Government 2020) it had become orthodox and unquestioned.

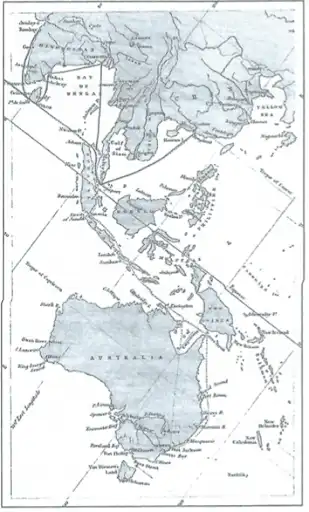

According to one British observer, “Australia was the first “mover” in terms of adopting the Indo-Pacific framework as national strategy, and this is because the concept helps Canberra centre itself (between the Indian and Pacific Oceans), more than has historically been the case.” (Hemmings 2019: 4). This history after the first European settlement in 1788 can, for heuristic purposes, be divided into three phases. The first till the federation of 1901 was that of six British colonies functioning as outposts of Empire with the essential of their relations with Britain and only limited contact with the immediate neighbourhood. Yet, as this pivoted map from 1848 indicates within the context of imperial ties – via Singapore to Calcutta to the west and Hong Kong to the east, the six British colonies in Australia were already, in a sense, part of an Indo-Pacific world (Pardesi 2019, Medcalf 2020). Despite the caricature of the rural stockman, the major proportion of the Australian population were, and are, coastal dwellers looking outwards (Drey 1994).

The second period from federation till World War II was symbolized by Australia’s dominion status attributed in 1924 and saw Australia as a key independent member of the British Empire with its security relations tied to London. The fall of the ‘impregnable’ British fortress in Singapore marked a turning point with Australia in 1942, in the words of the country’s then Prime Minister turning to the United States for its security “without any inhibitions”. Post-war, this phase was symbolized by the ANZUS alliance of 1951 and Australia’s status with Japan, of Australia, being an anchor of the US alliance system in the Asia Pacific.

From the early seventies a disjunct began to occur between traditional security relations and economic and trade relations. From this period Japan and, then, China replaced Britain (and the EU) as the country’s largest trading partners. Progressively, there began an attempt to create new institutions to reflect Australia’s new geopolitical status. These culminated in 1989 with the creation of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (forum) involving some twenty countries on both sides of the Pacific including major participants such as the US, China and Japan. Australia thus situated itself in the Asia-Pacific (Carr 2015) to the point of the Labor government under the time defining itself within a new hemisphere, and a former Australian ambassador to Beijing asking the question as to whether Australia was indeed an Asian country (Fitzgerald 1997) and others to later raise questions of a marginalized Australia within the Asia (Wesley 2011).

The second period from federation till World War II was symbolized by Australia’s dominion status attributed in 1924 and saw Australia as a key independent member of the British Empire with its security relations tied to London. The fall of the ‘impregnable’ British fortress in Singapore marked a turning point with Australia in 1942, in the words of the country’s then Prime Minister turning to the United States for its security “without any inhibitions”. Post-war, this phase was symbolized by the ANZUS alliance of 1951 and Australia’s status with Japan, of Australia, being an anchor of the US alliance system in the Asia Pacific.

From the early seventies a disjunct began to occur between traditional security relations and economic and trade relations. From this period Japan and, then, China replaced Britain (and the EU) as the country’s largest trading partners. Progressively, there began an attempt to create new institutions to reflect Australia’s new geopolitical status. These culminated in 1989 with the creation of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (forum) involving some twenty countries on both sides of the Pacific including major participants such as the US, China and Japan. Australia thus situated itself in the Asia-Pacific (Carr 2015) to the point of the Labor government under the time defining itself within a new hemisphere, and a former Australian ambassador to Beijing asking the question as to whether Australia was indeed an Asian country (Fitzgerald 1997) and others to later raise questions of a marginalized Australia within the Asia (Wesley 2011).

However, after the high point of the first 1994 Summit, faith in APEC as a geo-economic enterprise began to wane. Nevertheless, former US President Barack Obama’s 2011 support for a Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) involving eleven other countries with the US(4) (but excluding China) seemed to offer the promise of APEC achieving its aims. President Trump’s withdrawal from the TPP negotiations immediately on taking office marked a downgrading of an Asia-Pacific construct in the US. In reply, under Japanese leadership, Australia joined with the other ten participating countries to sign a Comprehensive and Progressive Transpacific Trade Partnership with the hope that a new US Administration would then join. At this juncture it appears President Biden has shown no intention of doing so or, any other free trade agreement for that matter.

In this period the “arc of instability” defined by defence planners was essentially seen in Southeast Asia including Australia’s large neighbour to the north, Indonesia. Former Prime Minister’s Rudd’s 2010 attempt to create a kind of concert of Asia, an Asia Pacific community, failed to gain traction and was strongly opposed by Singapore for failing to give due deference to ASEAN centrality. Within Australia itself politicians and senior public servants from Perth had become more influential. Their constituents in Western Australia, who look “across the Indian Ocean” and who see India as their closest neighbour never fully accepted defining Australia as merely having an Asia-Pacific orientation. Amongst these politicians former Labor Leader Kim Beazley as well as Stephen Smith as Foreign Minister and former Foreign Minister Julie Bishop (2018) and former Defence Minister Linda Reynolds from the Liberal Party offered a bipartisan vision of a transcontinental Australia with a “face” on the Indian Ocean as well as the Pacific. Amongst senior public servants, Peter Varghese, a former Australian ambassador to India and later Permanent Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade had an outsized influence on thinking in Canberra(5).

Australia’s Indo-Pacific approach is the result of an underlying philosophy in its foreign and security policy. Prompted by “a fear of abandonment” (Gyngell 2017) is the need for what a Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies, described during the height of the Cold War, a great and powerful friend. Since 1942 this has been the United States. In order to have this insurance policy for its security, in a sense a “premium” must be paid. Thus, Australia has been the only country to have fought in every war in which the US has been involved since 1914 even if such involvement has been questionable in terms of Australia’s national interest.

Objectives

Articulated in the notion of a Forward Defence strategu this evolving implies ensuring Australia’s territorial integrity by engagement well away from its shores. After the end of the war in Vietnam in 1975, in which some 500 Australian soldiers lost their lives, a competing concept of Fortress Australia gained traction in which it was argued that Australia should seek strategic autonomy and concentrate on defending its homeland and the immediate waters surrounding what is the fifth largest continent. In the 1980s and 1990s this partially isolationist stance was to be balanced with the need for Australia to be a “Good International citizen”. 9/11 and Australia’s enrolment in the US led “War on Terror” ended that period of being a kind of Sweden in the Antipodes. Yet the Fortress Australia ideal has not disappeared (Lemahieu et al 2021) but, in practice, the Australian tradition of basing its defence on the sending of expeditionary forces to fight alongside its protector, has remained.

The tension between ideas of Forward Defence and Fortress Australia is fuelled by two foreign policy debates within Australia itself. The first of these concerns the costs and benefits of the alliance with the United States (Lee 2018, Shortis 2021). Amongst the most critical of this alliance are four former Prime Ministers, two conservative, Malcolm Fraser (2014) and Malcolm Turnbull and two from the Labor Party, Paul Keating and Keven Rudd (2021). The second debate concerns China’s emergence as a competing power in East Asia and the level of threat it represents for Australia (Brophy 2021, Gilles & Jakobson 2017, Hamilton 2018, Hartcher 2021). If we are indeed in a period of the rise of a new hegemon (China) and the decline of the previous one (the US), where should Australia position itself (Lee 2018)?

Hugh White, possibly the most influential of Australia’s strategic thinkers has suggested in his seminal work, The China Choice, that Australia should accept that there will be two hegemons in the Asia-Pacific. This would imply that Australia should follow the example of its Southeast Asian neighbours and not choose between the US and the PRC (Stromseth 2019). Yet, questions of Chinese interference in Australia’s domestic politics, as well as Beijing’s aggressive behaviour in fortifying artificial islands in the South China Sea and militarising its fishing fleets, has led to an increasing influence of the anti-China hawks in Australia.

The two debates converge over the question as to whether Australia’s engaging itself definitively on the US side within the Sino-American contest in an Indo-Pacific is in Australia’s national interest. The announcement of AUKUS (see below) in mid-September 2021, is a watershed moment with two implications. On the one hand, in strategic terms Australia’s “arc of instability” no longer situated in Southeast Asia but in the South China Sea and, particularly, the Taiwan Straits. On the other, it means that Australia has bound itself with the US vision of the Indo-Pacific first articulated under the Trump Administration, as essentially concerned with containing and competing with China (Rudd 2021b). It is this aspect (McDonald 2021, White 2021), alongside the perception of it being a kind of imperially nostalgic club of the Anglosphere (Gyngell 2021) that has prompted the greatest criticism.

Means – Military Bases

Australia does not possess overseas military bases although there has been discussion of creating a naval base (possibly with the US) on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. However, an examination of the map of naval bases on the coastland of Australia shows their role in Australia promoting its security interests in the Indo-Pacific through the instrumentalization of its relations with the US. Australia, unlike its Southeast Asian neighbours, has always possessed a “blue water” navy designed to function well beyond its coastline. Australia’s submarine fleet is based in HMAS Stirling, near Perth in Western Australia, also a prominent port of call for the US 7th fleet. Further north on the Western Australia coast is a Naval Communication station in Exmouth shared with the United States. At Pine Gap in the centre of Australia a joint satellite surveillance and communication base established with the US in 196. Pine Gap is considered crucial for America’s global role.

On the east coast the naval bases in Sydney Harbour and Nowra/Jervis Bay provide the main points from which naval power (especially airborne naval power) is projected in the South Pacific. They are also the bases from which joint military activities are conducted with the US, and the only resident European power in the Indo-Pacific, France.

The redeployment of other military assets to the north, which began well before 2013, has positioned Australia, once again, to project these both within an Indo-Pacific security context, while giving further substance to the US-Australia alliance. The prime examples are the army bases in Darwin which in November 2011, during a visit by president Barack Obama, become open to the rotation of some 2,500 US Marines for training. This is planned to increase following the AUKUS agreement of mid-September 2021. The Darwin bases have, quite logically, also become essential for sea patrols by both the navy and the Air Force’s fleet of 14 Poseidon P. 8A maritime surveillance aircraft(6). This is the same aircraft being purchased by India in its first major initiative in not relying on Russia for its imported arms.. Australia has often parlayed its massive air space and numerous, military training facilities, such as the jungle warfare training centre in Cunungra and a major barracks at Enoggera in Queensland, to offer them to partners in the region including France and Singapore, as well as the US.

Joint naval exercises have become a key means to give expression to Australia’s role in the Indo-Pacific. The most important of these in the Indian Ocean, the Malabar Naval Exercise, began between the US and India in 1992, with Japan joining in 2015. Australia was initially a participant but withdrew under a Labor government in 2007 ostensibly because of Chinese opposition. It re-joined in 2020, shortly after the revival of the Quad (see below).

Alliances

ANZUS Treaty

Following the fall of Singapore in 1942 the cornerstone of Australia’s defence and security policy became an essentially bilateral alliance with the United States. Signed in mid-1951 the ANZUS Treaty was designed to assuage Australian and New Zealand fears of the resurgence of a militaristic Japan following the end of US Occupation. The outbreak of the Korean War gave to the Alliance a firmly Cold War character. The treaty began to unravel in 1984 When New Zealand declared itself a nuclear free zone and disallowed nuclear-powered vessels to its ports. Since 1985 a trilateral format has been replaced by a bi-lateral format, the Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN), held annually and alternatively in Australia and the US and involving the foreign and defence ministers of both countries.

Five Eyes

The Five Eyes (FVEY) is an intelligence gathering alliance involving the various espionage agencies of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the New States that emerged during the Second World War and the start of the Cold War. Four of its members are geographically within the Indo-Pacific, with the fifth, the United Kingdom, today seeking to reaffirm itself as an Indo-Pacific player.

The Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue)

Created after the tsunami of late December 2004 it involves four countries – Australia, India, Japan and the US – is not a formal alliance and was initially concerned with functional, especially maritime, cooperation (Le et al 2019). This remains the main concern of India. Under Labor Prime Minister Australia withdrew from the naval exercise (Malabar) that had characterized its early mandate but returned in November 2020. This followed the four countries becoming more aligned in their concerns over more assertive Chinese behaviour in the Indo-Pacific (Rudd 2021a). With virtual meetings in March 2021 and face-to-face meetings in late September 2021, the Quad is today the preferred institutional vehicle for reconciling the Indo-Pacific strategies of its four members.

AUKUS

The Australia United Kingdom United States Security Arrangement announced in mid-September 2021 is the second partnership with an Indo-Pacific agenda. While ostensibly created to enable Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines, the first of which will become available in 2040, it has symbolic importance. This suggests not only the strength of the alliance with the US, but of Australia’s acquiescence in a US vision of the Indo-Pacific as one designed to contain China.

Five Power Defence Arrangements (FPDA)

Signed in 1971, following Britain’s withdrawal from east of Suez, it involves as well as Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand and the UK. From 1971 till 1988 the Royal Australian Air Force commanded an airbase at Butterworth (near Penang) in Malaysia. Now controlled by the Malaysian’s themselves this base hosts aircraft and personnel from the other members on a rotating basis. Annual military exercises involving all five members give substance to the arrangement, which requires only “consultation” in case of an aggression against one of its members.

‘Trilaterals’

Australia is involved in a number of trilateral arrangements the most important of which is with Japan and the US. With India there also two ‘trilaterals’, one involving France and the second involving Indonesia.

Partnerships

As a self-conscious middle power Australia has invested both in maintaining and developing a rules-based international order (Emmers & Teo 2018) yet the bilateral relationship with the US remains at the core of the country’s security policy. Nevertheless, Australia is a founding and active member of a number of regional fora. These range from the intergovernmental South Pacific Forum (created in 1971), in which it is the heavyweight power in relation to the microstates and the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA). The latter, formally launched in 1997 is tripartite in nature bringing together actors from government, business and academia is concerned with functional subjects such as maritime security and fisheries and disaster risk management. Australia held the chairmanship from 2013 to 2015.

Within the Indo-Pacific region Australia finds itself in two types of fora in which to promote its interests. The first kind have a more security / confidence building function ranging from the ASEAN +1 ‘bilateral’ meetings, the ASEAN Regional Forum and, since December 2005 the annual East Asia Summit. The latter two also involve the PRC. Inclusiveness to engage China is more conspicuous in bodies with an economic (trade and investment) agenda. These include the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Australia itself initiated in 1989. As well as the existing Asia Development Bank, Australia joined the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Development Bank (AIIB) on its foundation in 2014. It is also a member of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Partnership (RCEP) alongside the 10 ASEAN countries plus China, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand. Announced in November 2020 this Free Trade Agreement should be ratified by end 2021. As mentioned previously, Australia is also a member of the competing/alternative – and initially US-led – Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for a Trans Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11).

Australian Government, Department of Defence (2013) 2013 Defence White Paper (accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper/2013/docs/WP_2013_web.pdf)

—————————————————————- (2016) 2016 Defence White Paper (accessed at: https://www.defence.gov.au/whitepaper/Docs/2016-Defence-White-Paper.pdf )

————————————————————— (2020) 2020 Defence Strategic Update (accessed at: https://www1.defence.gov.au/about/publications/2020-defence-strategic-update)

Australian Government, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2017) 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper (accessed at: https://www.dfat.gov.au/publications/minisite/2017-foreign-policy-white-paper/fpwhitepaper/pdf/)

Bishop, Julie (2018) “ASEAN: The Nexus of the Indo-Pacific”, Speech at the Asia Society, Washington DC, 8th March (accessed at: https://foreignminister.gov.au/speeches/Pages/2018/j

Brophy, David (2021), China Panic: Australia’s Alternatives to Paranoia and Pandering, Carlton VIC.: La Trobe University Press.

Carr, Andrew (2015) Winning the Peace: Australia’s Campaign to Change the Asia-Pacific, Carlton VIC.: Melbourne University Press.

Doyle, Randall (2018) The Australian Nexus: At the Centre of the Storm, Lanham MD: Lexington Books.

Drey, Philip (1994) The Coast Dwellers: a radical reappraisal of Australian identity, Ringwood VIC: Penguin Books.

Emmers, Ralph & Teo, Sarah (2018) Security Strategies of Middle Powers in the Asia-Pacific, Carlton VIC: Melbourne University Press.

Fernandes, Clinton (2018) Island Off the Coast of Asia: Instruments of Statecraft in Australian Foreign Policy, Clayton VIC.: Monash University Press.

Fitzgerald, Stephen (1997) Is Australia an Asian Country?, St Leonards NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Fraser, Malcolm (2014) Dangerous Allies, Clayton VIC.: Melbourne University Press.

Gill, Bates & Jakobson, Linda (2017), China Matters: Getting it Right for Australia, Carlton VIC.: La Trobe University Press.

Gyngell, Allan (2017) Fear of Abandonment: Australia in the World since 1942, Carlton VIC.: La Trobe University Press.

—————— (2021) Australia signs up to the Anglosphere, East Asia Forum, 19th September (accessed at: https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2021/09/19/australia-signs-up-to-the-anglosphere/)

Hamilton, Clive (2018) Silent Invasion: China’s Influence in Australia, Richmond VIC. Hardie Grant Books.

Hartcher, Peter (2021) Red Zone: China’s Challenge and Australia’s Future, Carlton VIC: Black Inc.

He Kai (2018) “Three Faces of the Indo-Pacific: Understanding the “Indo-Pacific” from an IR Theory Perspective”, East Asia: An International Quarterly 35 (2): 149-16.

Hemmings, John et al (2019) Infrastructure, Ideas and Strategy in the Indo-Pacific, London: The Henry Jackson Society (accessed at: https://henryjacksonsociety.org/publications/infrastructure-ideas-and-strategy-in-the-indo-pacific/)

Heydarian, Richard (2020) The Indo-Pacific: Trump, China, and the New Struggle for Global Mastery, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kersten, Rikki (2018) “Assumptions about alliances: Australia, Japan and the liberal international order” in Michael Heazle & Andrew O’Neil (eds), China’s Rise and Australia-Japan-US Relations, Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 195-218.

Le Thu Huong (ed.) (2019) Quad 2.0: New Perspectives for a Revived Concept, Canberra: Australian Security Policy Institute.

Lee, Sheryn (2018) “Contesting visions of ‘primacy’: The Australian perception of decline in the Asia-Pacific” in Michael Heazle & Andrew O’Neil (eds), China’s Rise and Australia-Japan-US Relations, Cheltenham UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 167-192.

Lemahieu, Hervé et al (2021) Beyond Fortress Australia, Sydney: Lowy Institute.

McDonald, Hamish (2021) “Signing Up”, Inside Story, 19th September (accessed at: https://insidestory.org.au/signing-up/)

Medcalf, Rory (2019) “Indo-Pacific Visions: Giving Solidarity a Chance”, Asia Policy 14 (3): 79-95.

——————- (2020) Indo-Pacific Empire: China, India and the Contest for the World’s Pivotal Region, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Natalegawa, Marty (2013) “An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific”, Keynote address at the CSIS Conference on Indonesia, Washington DC, 16th May (accessed at: http://csis.org/files/attachments/130516_MartyNatalegawa_Speech.pdf.)

Pardesi, Manjeet (2019) “The Indo-Pacific: a ‘new’ region or the return of history?”, Australian Journal of International Affairs 74 (2): 124-126 (DOI: 10.1080/10357718.2019.1693496)

Raby, Geoff (2020) China’s Grand Strategy and Australia’s Future in the New Global Order, Carlton VIC.: Melbourne University Press.

Rudd, Kevin (2021a) “Why the Quad Alarms China? Its Success Poses a Major Threat to Beijing’s Ambition”, Foreign Affairs, 6th August (accessed at: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-08-06/why-quad-alarms-china?)

—————- (2021b), “Morrison’s China ‘strategy’ makes us less, not more, secure”, Sydney Morning Herald, 18th September.

Shortis, Emma (2021) Our Exceptional Friend: Australia’s Fatal Alliance with the United States, Richmond VIC. Hardie Grant Books.

Stromseth, Jonathan (2019) “Don’t make us choose: Southeast Asia in the throes of US-China rivalry”, Foreign Policy at Brookings, October (accessed at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/dont-make-us-choose-southeast-asia-in-the-throes-of-us-china-rivalry/).

Tan See Seng (2013) The Making of the Asia Pacific: Knowledge Brokers and the Power of Representation, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Varghese, Peter (2021) “In Conversation: Public Lecture with Peter Varghese”, Perth: Perth USAsia Centre (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7FdbYlA4Mo&ab_channel=PerthUSAsiaCentre)

Wesley, Michael (2011) There Goes the Neighbourhood: Australia and the Rise of Asia, Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

White, Hugh (2012) The China Choice: Why We Should Share Power, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

—————– (2021) “From the submarine to the ridiculous”, The Saturday Paper, 367, 18-24 September (accessed at: https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/2021/09/18/the-submarine-the-ridiculous/163188720012499#mtr)

Notes

- 1.During the 2nd Session of our Observatory. Prof. Medcal describes himself as one of the ‘evangelists’ of the Indo-Pacific idea. See also Medcalf (2019, 2020)

- 2.The importance of regional narratives in underlined by Tan 2019

- 3.It is perhaps more than coincidental that Natelagawa completed his PhD in international relations at the Australian National University, Canberra, following a Masters at the LSE. Certainly his strategic writing is within the English School tradition of international relations with its stress on the idea of an international society ..

- 4.Under Japanese impetus the other 11 members completed negotiations for a “TPP – 1”, the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans Pacific Partnership.

- 5.Varghese 2021

- 6.This is the same aircraft being purchased by India in its first major initiative in not relying on Russia for its imported arms.