Home>Indo-Pacific Strategies>United States

United States

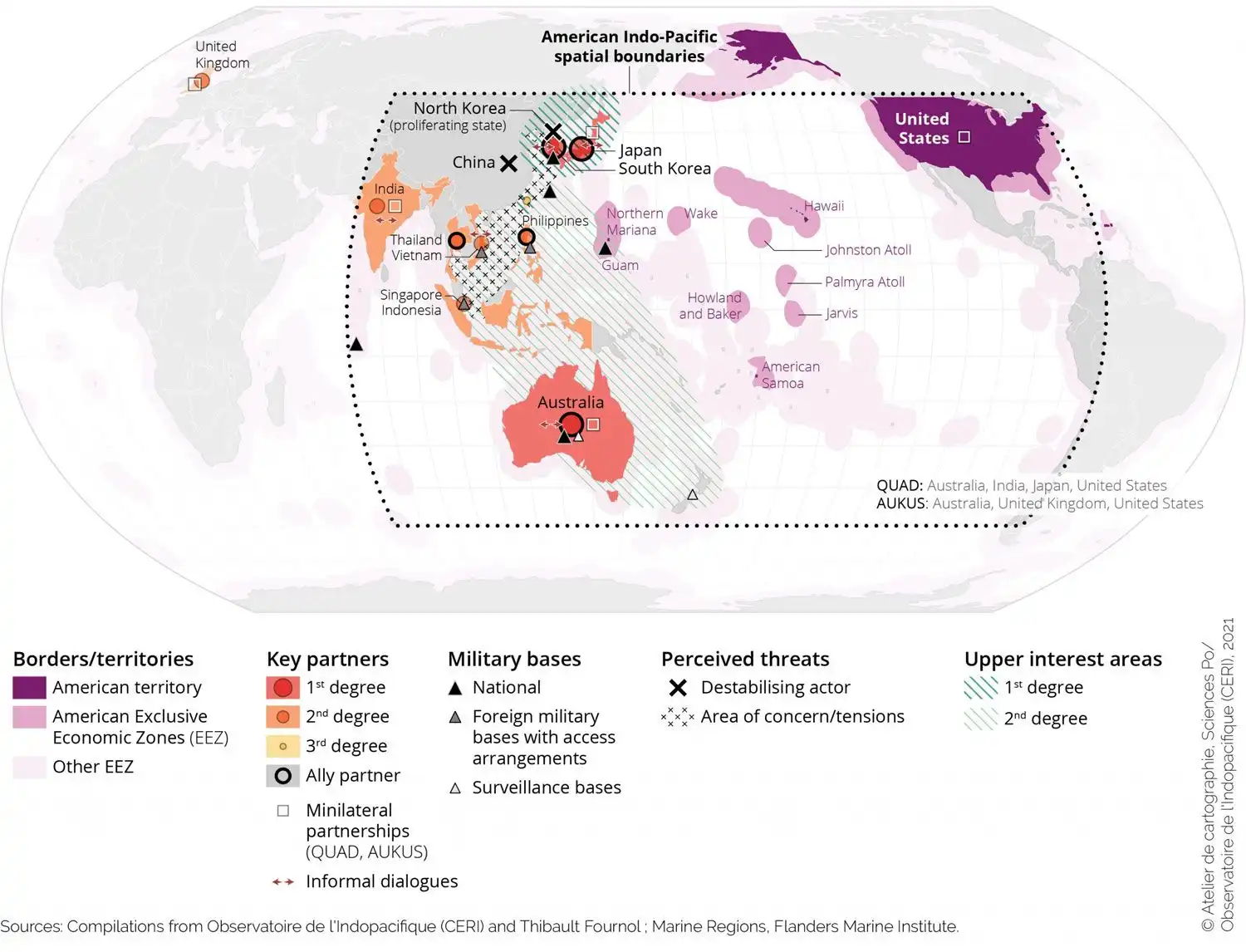

Indo-Pacific seen from United States 2021

Timeline and Main Documents

Building upon several decades of enhanced American focus and presence in the Asia-Pacific, the United States (US) has been, since the late 2010s, one of the leading proponents of the ‘Indo-Pacific’ construct. The initiatives undertaken by the Presidencies of William J. Clinton and, in particular, George W. Bush to strengthen and diversify the US presence across the Asia-Pacific were continued and further consolidated under the Presidency of Barack Obama. Building thereupon, the Donald Trump administration adopted a comparatively more confrontational stance toward China and decided to widen the geographical compass of its regional policy framework to embrace the broader ‘Indo-Pacific’ region. The Joe Biden administration has pursued and further developed such policy framework.

- In November 2017, in Vietnam, former President Trump outlined a vision for a free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) in which all the countries in the region may “prosper side-by-side, and thrive in freedom and in peace” as “as sovereign and independent nations”

- One month later, the Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy suggested that China was a “revisionist power” that sought to “challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity” through political, economic and military means; it further stressed that China aimed “to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, expand the reaches of its state-driven economic model, and reorder the region in its favor.”

- The 2018 National Defence Strategy called for expanding “the competitive space” in US relations with rising powers such as China. That same year, the name of the US Pacific Command (USPACOM) was changed into US Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM).

- The contours of the policy were further delineated, as detailed below, in reports published by Department of State and by the Pentagon in 2019

- In early 2021, the Trump administration then declassified the US Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific that identified as one of the main challenges the “maintain[ance] of US strategic primacy in the Indo-Pacific region and promot[ing] a liberal economic order while preventing China from establishing new, illiberal spheres of influence.”

- The Biden administration then published an Interim National Security Strategic Guidance in 2021 which stressed that US “vital national interests compel[led] the deepest connection to the Indo-Pacific.” The same point was reiterated in various speeches by Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Geography

Different bureaucracies within the US government have different definitions of the geographical areas covered by the ‘Indo-Pacific label:

- The Department of Defense’s Assistant Secretary of Defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs covers a broad geographical region which encompasses:

- Afghanistan/Pakistan/Central Asia: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

- China

- East Asia: Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Mongolia, Papua New Guinea, the Pacific Island nations, and North Korea

- South and Southeast Asia: India, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Diego Garcia, Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, East Timor, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- The US INDOPACOM’s Area of Responsibility covers, according to the Pentagon, “more of the globe of any of the other geographic combatant commands.” Specifically, the label covers – in the Asia-Pacific region – an area extending from Mongolia, China and Japan in the North, to Australia and New Zealand in the South as well as – in the Indian Ocean region – to India (while excluding Russia and Pakistan respectively).

- The State Department’s Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs covers the Asia-Pacific but not India which remains under the purview of the Bureau of South and Central Asian Affairs

- The Biden administration also created the Indo-Pacific Directorate in the White House’s National Security Council Staff that combines the directorate for Asian affairs – which traditionally covers China, Japan, the Koreas, Southeast Asia and Australia, and the South Asia directorate which oversees India. The new directorate is led by the Coordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs, a position currently occupied by Kurt Campbell.

Objectives

The goals of US policy toward the Asia-Pacific and then the Indo-Pacific—as well as the means leveraged to achieve such goals—have displayed both areas of continuity and discontinuity in the 21st century.

On the one hand, successive presidencies—including the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations—have continued to pursue the overarching goal of preserving the US hegemonic role in the region and in world politics which, in turn, has translated into three regional objectives:

- To promote regional stability to reduce the potential for miscalculation, unintended escalation and conflict

- To uphold foundational norms of the regional order, namely freedom of navigation and overflight, sovereignty, and the peaceful settlement of disputes

- To thereby also further US regional economic interests

By doing so, the US has not aimed to ‘contain’ China—as it did with the USSR during the Cold War—despite numerous analyses wrongly suggest. Containment refers to a strategy intended to limit the growth of Beijing’s capabilities by comprehensively isolating China from its neighbors and the world through diplomatic, economic, military and technological means. In fact, even if the US wanted to contain China, it would not be able to do so because of at least three factors: First, unlike the Soviet-American economic ties, the US and Chinese economies are too deeply intertwined and China is now profoundly integrated in global production networks. Secondly, political ideologies no longer crystallize competing blocs across the globe as was the case during the Cold War. Thirdly, all US allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific have very close economic ties with China (often more than with the US) and they are unwilling to balance (let alone contain) the PRC. With the exception of Japan and few others, most of them pursue a hedging strategy between Washington and Beijing.

Rather than seeking to contain China, over several decades the United States has aimed to channel and shape the trajectory of China’s rise within the US-led regional (and international) order, from a position of pre-eminence, through a mixture of cooperation and competition. US policy toward the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has thus been embedded in—and conceived as part of—a broader regional policy framework.

On the other hand, the relative balance between the cooperative and competitive elements of this policy framework have changed from one administration to the other. Identifying China as a ‘revisionist power’, the Trump administration substantially shrank the areas of cooperation with Beijing, focusing instead on countering its strategic rival through enhanced competition in a wide range of diplomatic, military, economic and technological areas. Likewise, while previous American administrations had consistently sought to integrate China in the post-World War II ‘rules-based order’, the Trump presidency signaled a departure from such goal—exhibiting a more pessimistic stance toward the possibility of achieving such outcome. And while the Biden administration is still in the process of revisiting the contours of its policy toward China and the ‘Indo-Pacific’, it has slightly recalibrated its approach toward the PRC emphasizing that its “relationship with China will be competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be, and adversarial when it must be.”

Means

Despite some bombastic claims by former President Trump, the evolution of the US-led system of alliances and bilateral partnerships in the region displays very significant continuity across the Obama, Trump and Biden administrations. In the early Cold War, the US had developed a system of exclusive bilateral alliances in the Asia-Pacific. Commonly referred to as the “hub-and-spokes” system, it comprises five bilateral relationships (with Australia, Japan, South Korea, Thailand and the Philippines), whereby the different allies (or “spokes”) are connected to the US “hub” but with almost no interaction amongst them. Nonetheless, over the past two decades, this system of strictly bilateral alliances has been gradually and cumulatively supplemented by a network of interwoven bilateral, minilateral and multilateral arrangements which is characterized by greater connectivity through variable geometries of security cooperation amongst different allies and a broadening range of non-allied partners.

Successive administrations have sought to respond to the challenge posed by China’s rise by reordering the US-led system of alliances and security partnerships in East Asia. The initiatives undertaken under the Presidencies of William J. Clinton and, in particular, George W. Bush, to move beyond the hub-and-spokes system by networking US allies and partners—as well as the PRC—into an overarching architecture were continued and further consolidated under the Presidency of Barack Barack Obama and, subsequently, by Donald Trump.The Trump administration officially labeled to the reordering of its alliances and security partnerships in the region a “networked security architecture,” a label which had already emerged in the academic literature. As explained by former Secretary of Defense James Mattis, the US “will continue to strengthen our alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific to a networked security architecture capable of deterring aggression, maintaining stability, and ensuring free access to common domains. With key countries in the region, we will bring together bilateral and multilateral security relationships to preserve the free and open international system.” Similarly, his successor, Patrick Shanahan, unambiguously states that the US is “strengthening and evolving US alliances and partnerships into a networked security architecture to uphold the international rules-based order.” The 2019 Pentagon’s Indo-Pacific Strategy Report went at great length to detail the range of partnerships, minilateral groupings and multilateral fora in the Indo-Pacific through which the US continued to develop a networked security architecture in the region. The networked security architecture cultivated by the Trump administration—and subsequently by the Biden Presidency—has been characterized by the very same constitutive elements as under previous administrations:

- Strengthening bilateral mutual defense alliances, most notably Japan, South Korea and Australia (as well as the Philippines and, to a lesser extent Thailand)

- Consolidating and diversifying bilateral and minilateral (tri/quadrilateral) security arrangements in the region:

- Bilateral Partnerships, most notably with Singapore, Vietnam, India, and New Zealand. Since the Obama administration. Washington has also sought to further diplomatic and security cooperation in the region with the United Kingdom and France and more broadly with European Union.

- Minilateral Groupings such as the Trilateral Strategic Dialogue with Japan and Australia, enhanced trilateral intelligence cooperation with South Korea and Japan, and the so-called “Quad” with Australia, India, and Japan

- Strengthening the US engagement in multilateral institutions in the Asia-Pacific, such as ASEAN, ARF, and in the security domain the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus (ADMM-Plus).

Accordingly, notwithstanding the vagaries in some of President Trump’s foreign policy pronouncements, the US approach to alliance dynamics in the ‘Indo-Pacific’ displays considerable continuity across administrations.