Home>"Across the Blocks": A Learning Expedition Into Smart Cities

22.10.2020

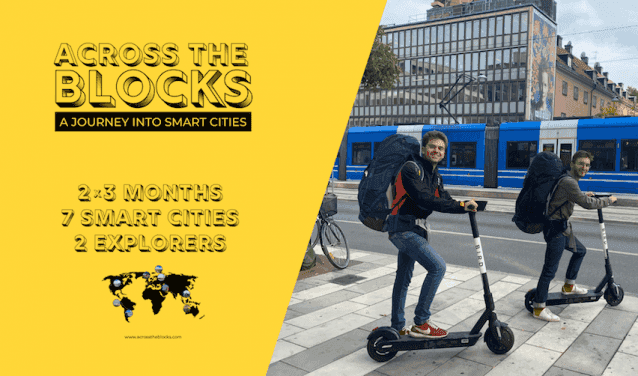

"Across the Blocks": A Learning Expedition Into Smart Cities

In January 2020, recent graduates Benoît Gufflet and Dimitri Kremp set off on a learning expedition to explore seven “smart cities”. They published their report, "Learning Cities", on 22 March, 2021: an immersive and interactive account exploring and deconstructing the fantasies of the Smart City. We spoke to them in October 2020 about their journey, what they’ve learned about “smart cities,” urban dwellers and pursuing a learning expedition during a global health crisis.

You launched “Across the Blocks” in January 2020 with a plan to travel to seven cities. Can you tell us a bit about the origins of this project?

Benoît GUFFLET: The project was born during our 2019 trip to Mexico. We were surprised by the density of the city and wondered how the digital world could provide solutions to problems such as traffic congestion or energy consumption. We started to wonder how technology could transform cities and we got interested in the topic of smart cities.

Dimitri KREMP: After our trip to Mexico, we spent a year planning and trying to find sponsors. We were able to benefit from the support of Bouygues Immobilier (our main sponsor), Wavestone, as well as Sciences Po and HEC. These entities decided to support us because we were ready to go out into the field and look behind the city's marketing campaigns. This is something we are quite proud of: by going out into the field to study what cities call "smart" projects, we are able to develop our own opinion about them, which is invaluable to our sponsors. When you log in online only, it is difficult to truly grasp the lives of city dwellers and assess the success of digital initiatives. However, if you ask citizens on the street directly what they think about a project, you find that there is still room for improvement.

What is a “smart city”?

DK: Unfortunately, there is no easy answer to this question: everyone seems to have their own definition. One way to understand this is to distinguish between smart cities in theory and in practice. In theory, a smart city is a city in which data is used to transform the city and improve the quality of life of citizens. In practice, when we go into the field, we realize that it is not only a question of the digitization of a city, but also of the collaboration between private actors and governance. In fact, this is one of our main findings to date: each city appropriates this idea of “smart city” in its own way. To better understand how this concept is applied in real life, we need to take a more sociological approach and study its inner workings. For example, to understand how Medellín implements its smart city projects, it was imperative to understand its history, its challenges and to know its people.

What are you looking for when you visit these cities?

BG: For every city we visit, we follow a four-theme approach: 1) The city’s strategy to become a “smart city”; 2) The city’s “smart platform” or monitoring platform, but also any digital service provided by the city to citizens; 3) The user participation: we try to identify different ways users are participating, and what role residents have in trying to make the project take life; 4) The testbed area in a specific neighbourhood. This four-theme approach has given us a framework with which to study the city, even though each city has its own way of understanding and implementing smart city projects.

What surprised you the most during the first part of your mission?

BG: In each city we travel to, we first identify a flagship programme or initiative that has been a trigger in labelling the city as “smart”. For example, Rio de Janeiro is famous in the "Smart City" ecosystem for its Centro de Operações (Operation Center) built with the help of IBM: a Nasa lookalike control room for the city. But as we visited the center, we discovered that this massive infrastructure had far less impact on the city's management, using a very small portion of the data it collects. In fact, most of the flagship projects that we had identified in each city turned out far less impressive, as if they were nothing but fantasies. This is what surprised us the most: the reality of most "smart city" projects is not that very advanced and sophisticated. The reasons for this are both technical and societal. Often, the tech is not yet ready for these smart solutions as it is still learning how to capture and analyse data. Plus, citizens are becoming more aware of the need to protect their personal data, and are starting to resist private companies’ initiatives based on the collection of digital information. In Toronto, for example, a Google-led initiative called Sidewalk Labs was called off due to resident opposition. In truth, besides Singapore which is a very special case, we haven’t yet found a real “smart city,” but have rather been exploring “learning cities,” which are trying new solutions, making mistakes, and learning from them.

Centro de Operações (Operation Center) in Rio de Janeiro © Across the Blocks

What is the role of the urban resident in a smart city today? Should the urban resident resist or fear ‘smart city’ tech initiatives?

DK: The role of the urban resident is still quite ambiguous today. When prompted, residents say they are quite reluctant to share their data. But on the other hand, people use and consume many digital services to facilitate their everyday lives when it comes to travel and mobility, using apps such as Waze or Airbnb. However, as a general trend, we have observed that urban residents are eager to participate in the life of their cities at a local scale. Thanks to our field research, we have seen that tech can really play a role in terms of civic participation when it comes down to smaller communities and neighbourhoods.

BG: The population seems to be quite afraid of surveillance and so the question often comes up, and yet, in most of the projects that we’ve identified, there are not actually many tech initiatives that are watching or collecting data on the population. We’ve noticed a strong paradox within people: they use their smartphones for anything and everything while claiming they are against the collection of data, yet it is data that allows these apps to function so successfully.

You were about halfway through your mission when the Covid-19 pandemic brought everything to a halt. What has this health crisis taught you about smart cities and your mission in general?

DK: It was really eye-opening to witness the peak of the crisis in Singapore, where we were actually under lockdown. Singapore is a particular case - it is probably the most advanced case of a smart city, notably thanks to its “smart nation” programme. We witnessed in real-time how tech and digital programmes can mitigate the propagation of a virus like Covid-19. Singapore has a governmental agency called GovTech and within just a couple of weeks, they managed to create really efficient services that could be used by the population to get informed or to change their behaviour to stay safe regarding Covid-19. For example, the government launched a web portal called “Safe Distance @ Parks,” which provided real-time information on parks’ crowdedness so that people could know when to visit or avoid them. They also used Whatsapp loops to transmit clear information about the propagation of the virus and prevent the spread of rumours. It was a quite efficient solution and it was very interesting for us to witness.

How have your studies at Sciences Po helped you or prepared you for this project?

DK: We are both recent graduates of the dual degree programme between Sciences Po and HEC. Although the courses we took at both universities were not directly related to the topic of smart cities, Sciences Po gave us the network that allowed us to bring this project to life. When we were first starting out, we spoke with several of our professors who helped us to imagine the project. We also met with “smart city” experts such as Antoine Courmont, a researcher at the Chaire Villes et Numérique (Cities and Digital Technology Chair), who gave us his vision of the concept and what we could do with it. We also spoke with Mathieu Saujot, Senior Research Fellow at IDDRI (Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations). We leveraged this network of knowledge within the Sciences Po community and that was a big step forward.

BG: During the expedition, we were especially surprised by the strength of the Sciences Po alumni network. We met alumni in every city. In Rio, we met with an alumnus who worked on the 2016 Olympics who gave us really good insights on the impact of the Olympic Games in the city. We also became friends with different students from Sciences Po both in Colombia and in Canada - we were even hosted by 3rd-year students in Toronto. A Sciences Po alumnus who is now the head of the SOCAN, the Canadian SACEM (Society of Authors, Composers, and Publishers of Music) spent two hours telling us about his life and career thus far, which was really inspiring!

Is there anything you will change about how you explore cities in the second part of your mission?

BG: We are not changing anything in terms of methodology. We are still going into the field and conducting interviews, some of which are now digital, but we’re still able to arrange physical meetings when the health situation permits it. However, our personal approach and understanding of the project have evolved as we have learned to become more resilient to the fact that things may not go as planned.

What advice would you give to students considering undertaking this type of project?

DK: I would personally encourage students to take the leap and go forward with this type of project. Learning expeditions are a really innovative way to combine research and entrepreneurship since you have to establish a structure or create an association to run your mission. It is very complete and instructive.

BG: I would tell any student considering a similar project to trust themselves and not give up. We’ve had some tough times along our journey but we have always stayed positive. We were able to resume our expedition even with the health crisis and still have the support of our sponsors, which proves that they’re still trusting us!

More information